Yet there is evidence that in writing Doctor Who and the Planet of the Daleks Terrance swapped notes with another writer, and as a result ensured continuity with a book from a completely different publisher.

As I reread this book, I was also conscious of Terrance in dialogue with himself, in that it is a novelisation of a TV story on which he had been script editor. He fixes some things here that he didn’t fix then, but he also avoids the temptation to tinker too much.

More than anything, I was conscious of pace. On TV, Planet of the Daleks is a fast-moving action adventure, full of incident and forward momentum — what a delight it was to watch some years ago with my young son. But in that haste, some elements of the plot that we rattle past don’t hold up if we stop for a proper look. The novelisation addresses some of this, but I think we can also see a similar fast-paced, forward momentum at the typewriter. There are things here I would fix...

As usual in this period, Terrance worked from the camera scripts rather than rewatching episodes as broadcast. We can see this from the opening page of the novelisation, where Jo helps the wounded Doctor. In the script, she presses a button in the TARDIS, a,

COUCH SLIDES OUT FROM THE WALL & HE FALLS ONTO IT.

It’s a “couch” in the novelisation, too (p. 7). But on TV, it’s a pull-out bed, part of a unit of cupboards and drawers. Once on it, the Doctor directs Jo to a “locker” above the bed, in which he stores the audio log for the TARDIS.

But in the script, the Doctor says the log is, “In a locker under … here”. Stage directions say he points to it, but don’t specify where this locker is or what it is under. Terrance rationalises this by placing the,

“locker in the base of the [TARDIS] control console” (p. 7).

A little later, the script specifies that Jo “goes to a locker”, presumably a different one, from which she “pulls out a suitcase” containing a change of clothes suitable for the conditions on the planet Spiridon, where they have just landed. Terrance makes this a,

“clothing locker in the wall” (p. 10).

On screen, we don’t see from where she gets her change of clothes. (Lockers are clearly de rigueur in a spaceship, as the Thal ship also has a wardrobe-like locker (p. 17), named as such in the script.)

The audio log recorder is more than a simple Dictaphone; we’re told here that it has eternal batteries and unlimited capacity (p. 7), making it a bit more sci-fi than ordinary secretarial equipment.

As per the TV story, the vegetation on Spiridon spits liquid at the TARDIS and at people. This is meant to be horridly visceral, and Terrance makes them “spongy, fleshy plants” (p. 10), with the results of this “rubbery spitting” (p. 20) at once “viscous” (p. 11), meaning thick and sticky, and readily familiar:

“The plant spat milky liquid at her” (p. 14).

I suspect a modern editor would cut either “fleshy” or “milky”; both is a little suggestive.

When the TARDIS is covered in rubbery plant spit, no air can get in from outside, leaving the Doctor at risk of suffocation. It is nuts that the TARDIS relies on external air, not least because the ship travels through the Space/Time Vortex where there isn’t any. But this jeopardy is all as per the TV story, the fault of writer Terry Nation and, er, his script editor at the time. Terrance at least has the Doctor here acknowledge that he shouldn’t have let his emergency air supply run low (p. 13). Bad captain of the ship!

The Doctor then tries the TARDIS doors which, because of the rubbery spit outside,

“yielded but would not give way” (p. 18).

This is a rare example of Terrance employing the wrong word, as “yielded” means to stop resisting. (Writer Jonathan Morris suggests “yielded a little” would work better.) There’s something similar when the Thals first see the TARDIS:

“they realised that the tall, oblong shape was the ‘Space-Craft’ they were seeking” (p. 19).

Why would a space-faring crew capitalise and hyphenate “spacecraft” as if it were some exotic new concept? ETA: My pal Dave Owen suggests that the quotation marks are there to emphasise how unlike a spaceship the TARDIS seems to these Thals. Hmm, maybe.

I love the word “oblong”, too, but it means a two-dimensional shape. The TARDIS is, roughly, cuboid or a rectangular prism. A more apposite word is “box”, which would also convey limited size.

We’re told early on that,

“Jo had often heard the Doctor say that the TARDIS was invulnerable to outside attack” (p. 10).

This invulnerability is restated on p. 124, this time not as something Jo has heard but as fact care of the author. Terrance should have known better from TV stories on which he was script editor. For example, the TARDIS is destroyed in The Mind Robber (1968). It has only just reassembled itself when, in the opening moments of The Invasion, missiles are launched at it. The Doctor desperately works the controls to move his ship out of the way, surely because he doesn’t expect the TARDIS to survive the encounter.

In Death to the Daleks (1974), again written by Nation and script edited by Terrance, the TARDIS is subject to eternal attack by a sentient city, which drains away the ship’s energy — the Doctor then struggling to open the door of the TARDIS is a direct echo of what happens here. In the very next story Terrance was to novelise, Pyramids of Mars (1975), a psychic projection of Sutekh is able to enter the TARDIS. In novelising that, he didn’t — or wasn’t able to — amend the lines here. He moved forward, not back.

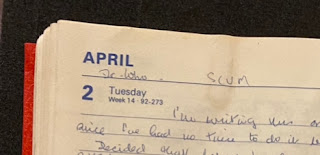

I’m not the only person to nitpick such stuff. Based on my estimated lead time of 7.5 months, Terrance wrote this novelisation in March 1976. The following month, he received a letter from fan Richard Landen listing errors in the original version of The Making of Doctor Who (1972), in the hope that these could be corrected for the revised edition — Terrance’s next writing assignment. On 29 April, he was the guest of the newly formed Doctor Who Appreciation Society at Westfield College in London. As Jeremy Bentham reported in the fanzine TARDIS in July,

“The evening commenced with a slightly nervous former script-editor explaining that he was often dubious about talking to dedicated Dr Who fans, since they tended to know more about the show than he did.” (Vol. 1, no. 8, p. 8.)

Soon, this scrutiny would change the way Terrance approached his novelisations.

For the time being, we can see other influences on the novelisation of Planet of the Daleks. Terrance describes the jungle of Spiridon, with its varied flora and fauna, as “one gigantic beast” (p. 9). That idea of a whole ecosystem being a single, complex lifeform was relatively new; Robert Poole suggests in his book Earthrise that it’s a consequence of the space age, and people — starting with the crew of Apollo 8 in 1968 — seeing the disc of the Earth for the first time.

Real space travel seems to inform Terrance’s description of the Thal spaceship, too. In the script for Episode One, stage directions say it is has a “HULL AND FINS” but is,

SHAPED RATHER MORE LIKE A GUIDED MISSILE THAN ANYTHING WE HAVE SEEN IN U.S. SPACE MISSIONS … A DESIGN THAT SHOULD APPEAR STRANGE AND ALIEN TO EARTH.

Terrance doesn’t use the analogy of a missile:

“The ship was small and stubby, vaguely cigar-shaped. Hull and fins were badly damaged” (p. 14).

The hull is, he says, “picked out in blue and gold” (ibid). The script describes, simply, an “interior”. But Terrance has Jo explore the “nose-cone” and “flight deck” (p. 15). Nation wanted the ship to be alien and unfamiliar; Terrance made it seem a more like a real, contemporary rocket — something readers could easily visualise.

The book is peppered with analogies that do something similar, likening the strange, sci-fi elements to things readers would know. The prone Doctor at the start of the story is like an effigy on a Crusader’s tomb (p. 10) — not just any stone effigy, but a heroic knight. Jo likens the alien temple she finds to something from Brazil (p. 11). The exposure of an invisible Dalek is like something from a children’s “magic” drawing book (p. 25).

Jo later hides from a Dalek behind an instrumental panel, where there is a,

“gap, rather like that between a sofa and a wall” (p. 52).

That is, of course, exactly how many readers would respond to seeing Daleks when watching Doctor Who. The enormous ventilation shaft in the Dalek base is like a “chimney” — a word used several times — from which the Doctor emerges like a cork out of a bottle (p. 76). The Thals behave, at one point, like children in a playground (p. 84), while the Doctor’s efforts to recover a bomb from between massed ranks of Daleks is,

“like a ghastly slow-motion football game” (p. 116).

This is a simple, quick means to convey meaning to younger readers — the intended audience of these books. But I think it also serves to make the events seen on screen a bit less strange and scary.

That’s not to say this is a wholly bowlderised version. On screen we’re told twice in dialogue that the Thals are on a “suicide mission”. The word “suicide” appears much more frequently in the novelisation, and not only in reference to the Thals. At the end of the story, Terrance gives Jo a moment to acknowledge the earlier “self-sacrifice” of brave Wester (p. 123), whereas on TV his death is a relatively quick, sudden shock and then we move on, without a backward thought.

Wester and the other Spiridons are invisible, which on screen makes for some fun visuals as stuff floats about via the magic of roughly fringed yellow-screen. Terrance makes the scenes — the un-scenes — with these invisible people suspenseful and involving; Jo’s first encounter with them (p. 17) is deftly, atmospherically told, and more tense than the TV version.

The Daleks insist that the Spiridons wear big furry coats to make them visible. Terrance, working from the script, doesn’t mention the colour (p. 46); on screen, they are a distinctive shade of purple. Wester abandons his coat to go unseen when he attacks the Daleks (p. 104). The implication, surely, is that he attacks them naked — but Terrance doesn’t spell this out.

Well, no, that might not be appropriate. Yet we’re told that the Doctor “cursed fluently in a Martian” (p. 109), and when our heroes succeed in one part of their mission,”,

“Jo and the Doctor joined the jubilant Thals in an orgy” (p. 100)

All right, it’s an “orgy of hand-shaking and back-slapping”. But is that really the appropriate word?

Many of the more technical words used here — “allotrope” (p. 47), “hermetically” (p. 86), the frequent use of “catwalk” and “arsenal” in the final part of the story — are as per the script. But Terrance adds some of his own: “flush” (p. 52), meaning to be fitted perfectly, or the way confused Daleks “milled about” (p. 66 and p. 104).

The young Thal called Latep, a potential romantic interest for Jo, is introduced as a,

“tall muscular man with a fresh open face” (p. 45).

That word is used again — on p. 81 it’s a “cheerful open face”. Terrance later employed “open” to describe the Doctor, again as a synonym for young.

Then there’s Terrance’s idiosyncratic approach to capitalisation, which we have seen before. Here, that includes Space/Time Vortex (p. 7), the study of Space Medicine and the threat of Patrol (both p. 16), “Space-Craft” (in quotation marks, p. 19), Time (p. 21), Command Centre (p. 35), Thal Communications (p. 44), and Galaxy (p. 78).

The Daleks on Spiridon are led variously by a Dalek Commander (p. 42), Dalek Expedition Commander (p. 84) and Expedition Commander (p. 108) — all the same single Dalek. His subordinate is the Dalek Scientist (p. 84), aka the Dalek Chief Scientist (pp. 93-4). But there’s no capital letter for the Dalek scientific section (p. 42).

The Expedition Commander answers to the Dalek Supreme (p. 108) from Dalek Supreme Command (p. 44), who we’re told here — but not in the TV version — is second only to the Emperor (p. 109). That’s surely Terrance recalling something of the Doctor’s encounter with the Dalek Emperor in The Evil of the Daleks (1967), a story repeated on TV just as he joined the production team of Doctor Who. But I think it is also doing something with the lore of the Daleks, to which I will return in a moment.

Taron is a Thal doctor, lower case (p. 19), for all that Space Medicine is up. The Doctor’s sonic screwdriver is also lower case, as is the “some kind of pterodactyl” identified by Taron (p. 83), who seems to know a lot about the history of life on Earth, given that the Thals think it is a legend, not a real place (p. 16). Terrance also hyphenates “wild-life” (p. 86).

The Thals are equipped with the latest futuristic kit: plastic beaker, plastic notebook and plastic carton (p. 17), plastic cape (p. 19), plastic box of food concentrates (p. 22), plastic wrapping for bombs (p. 42), and plastic rope (p. 75). On Earth, most plastic is derived from fossil fuels, whether gas or petroleum. The implication, then, is that oil is abundant on Skaro. Why, then, do the Daleks employ static electricity?

Terrance also tells us a bit more about Thal culture; they prepare their “rubbery cubes” of food (p. 22) on “tiny atomic-powered stoves”.

“Soon they were all washing down the tough, chewy food-concentrates with delicious hot soup” (p. 78).

It’s characteristic, I think, that what Terrance adds to this suspenseful, thrilling story, is a bit where they have a nice meal.

The Thals aren’t exactly the most liberated bunch. Rebec, the sole Girl One, adds little to the story beyond aggravating Taron, because being in love with her means he can’t think straight. That’s in the TV version, but Terrance doesn’t exactly improve things by having Rebec “sobbing with fear” (p. 67) as they all escape from the Daleks, and then again on p. 79, when the Doctor dispatches Jo to console her.

That said, the male Thals are also under pressure here. Terrance uses these moments to underline that the Doctor is a kind and canny hero: he makes allowances for Vaber’s rudeness because he knows the man is tired and lashing out (p. 21); when he sees that Codal needs cheering up, he thanks him for earlier bravery (p. 38). The Doctor is shrewd, but also takes time to form an opinion — such as when he acknowledges to himself that he,

“knew too little of the situation on Spiridon to form a proper judgment” (pp. 28-9)

There’s a fair bit added here about positive thinking. The Doctor is “cheerful and confident” (p. 107) as he heads into danger, and “as always, making the best of things” (p. 28). He tells the Thals, in a sequence not in the TV version, that they must guard against self-doubt — the “enemy within” (p. 84).

Terrance underlines other heroic aspects of the Doctor. For example, when running away from the Daleks at one point, we are told his route is not “completely at random” (p. 55), but purposefully leading him and his friends back to the lift so they can escape. We’re told that there is nothing the Doctor can do to save a Thal called Marat; even so, the Doctor is compassionate, with an “anguished look” (p. 60). When the bomb they need falls into a pit of 10,000 Daleks, the Doctor hurries after it “without hesitation” (p. 115) and emerges, triumphant, by climbing up the side of a Dalek then performing a “flying leap” (p. 116).

Sadly, Jo isn’t similarly bolstered in the prose version of the story. She’s described simply as “very small and very pretty” (p. 7), and her smallness comes in useful several times. She’s loyal and brave, as in the TV story, but all the novelisation really adds is that she has a dream about a holiday on the French Riviera (p. 85).

This is a rare hint of Jo’s life outside the events seen on screen. We learn all sorts of incidental details about the Doctor, too. For example, while he is down among the 10,000 Daleks,

“Talk about Daniel in the lions’ den, he thought” (p. 115).

So he’s familiar with the Old Testament. At this point in his lives, the Doctor has not been hot-air ballooning (p. 66). He cups his hands over his ears because of the changing pressure in the lift (p. 37), a rare example of this incarnation of the Doctor not having superhuman powers.

Yet it is uncharacteristic of this Doctor to be clumsy, stepping on and breaking the modified audio log recorder that proved so useful a weapon against the Daleks (p. 51). That weapon is possible because the Daleks imprison the Doctor and the Thal called Codal without “really” searching them. As well as the recorder, the Doctor has his sonic screwdriver and Codal an atomic-powered motor (p. 41). It is as per the TV version, but not typical of Daleks, and Terrance makes no attempt to explain it away.

By contrast, when a Dalek doesn’t immediately blast the Doctor, we’re told that it was “astonished” (p. 55) by his sudden appearance. That makes the moment more credible. There is more in this vein when the Doctor and his friends escape from a locked room (by floating up the chimney) and,

“The astonishment of the Daleks was almost ludicrous” (p. 66).

I think Terrance meant that their astonishment was funny, with the Daleks in “utter confusion”. But “ludicrous” suggests foolish, unbelievable. “Hilarious” or “surreal” might be better; “ludicrous” is not quite on the mark.

When the Doctor returns to this locked room later in the story, he notes the ruins of the Dalek anti-gravitational disc, but there’s no reference to the Dalek that tumbled down the chimney with it, or the other Daleks it crashed into. Did those Daleks survive — or is there a rank of Dalek that does the tidying up, and prioritised clearing the bodies before tackling the wreckage?

We glean other bits of Dalek lore here. The Doctor, for example, knows they build,

“bases underground wherever possible [as] daylight and open air meant nothing to them, and they flourished best in a controlled underground environment” (p. 37),

This is new information, but consistent with the bunker from Doctor Who and the Genesis of the Daleks, which (as we saw) Terrance linked to the city seen in the Daleks’ first TV story. The Doctor also refers here to the“first Dalek war” (p. 20), ie the events of that story, but there is no asterisk to “See Doctor Who and the Daleks”. On TV, that was simply “the Dalek war.”

In adding an ordinal, perhaps Terrance simply meant to differentiate the events of that story from the conflict going on around this book — ie the “space war” against Earth and Draconia. But I think adding “first” implies a series of wars, the Daleks a recurring menace in considerable force. It’s not what we’ve seen in TV adventures, which tends to involve small numbers of Dalek in small-scale machinations.

It’s much more like the kind of thing we see in media other than TV — the comic strips and annuals in which the Daleks conquer whole star systems. And I don’t think that’s a coincidence.In the TV version of Planet of the Daleks, the Daleks are on the planet Spiridon to exploit a rare geological feature: what dialogue refers to as “ice volcanoes”. In the novelisation, Terrance uses a shortened term, “icecano”. But I don’t think that’s his coinage. The word was first used on p. 21 of Terry Nation’s Dalek Annual 1977, published by World Distributors in September 1976 — a month before this novelisation. Here it is as per that book, describing a feature on the Dalek planet Skaro:My sense is that these lavishly illustrated annuals, printed on good quality paper to a high standard, had much longer lead times than prose-only novelisations on regular newsprint. That surely means that “icecano” was coined for the annual, before Terrance even started on this novelisation.

Somehow, the term was then shared with him. My guess is that Terry Nation, working on the annual and knowing that Terrance was going to novelise this story, suggested he use the word. It was Nation, then, who encouraged Terrance to join up terms and lore, building an expanded universe of the Daleks far more rich and spectacular than we could ever see on screen.

The irony is that, in Planet of the Daleks, Terrance made his own massive contribution to Dalek lore. His amended ending to Frontier in Space, in which the Doctor is shot by the Master, leaves our hero in no state to set the controls of the TARDIS in pursuit of the Dalek army. Instead, in Terrance’s version, he uses the telepathic circuits to ask his own people for help.

For the first time in their long history — to the best of our knowledge — the Time Lords intervene against the Daleks. In doing so, they help prevent a space war but spark a wholly different conflict. This is the start of the Time War…

*

Thanks for reading, sharing and responding to these huge long posts about the 236 books written by Terrance Dicks. I am glad they are still popular, though they take a fair bit of time to research and write, and incur various expenses. With other pressures and commitments, and the freelance world a bit sparse, I can only justifying continuing with your kind support. So do please show your appreciation…

Next time, more Mac collaboration (or not) with The Making of Doctor Who, a book that is very largely about anything but the making of Doctor Who…