Friday, October 31, 2025

Bergcast #39 - The Blu-ray Xperiment

Monday, June 09, 2025

The Legend of Nigel Kneale 2. Enemy From Space

Among the many goodies included in the set is the second part of the documentary me and Brother Tom have produced with Eklectics about Quatermass creator and writer, The Legend of Nigel Kneale.

As with the first part, included on the collectors' edition of The Quatermass Xperiment, the documentary is presented by Toby Hadoke and includes interviews with Kneale's biographer Andy Murray, Dr Tom Attah, Joel Morris, Brontë Schiltz and Jane Asher. This second part also includes two other on-screen contributors... but wait and see.

Friday, April 25, 2025

The Legend of Nigel Kneale: 1. The Creeping Unknown

Among the many, many treats listed on the Hammer site is this:

The Legend of Nigel Kneale: The Creeping Unknown. Who was Nigel Kneale? Toby Hadoke investigates the man and his influence in part one of a brand-new two-part documentary.

Produced by me and my brother Tom for Eklectics, and directed by Jon Clarke and edited by Robin Andrews, this authoritative new documentary includes expert analysis from Dr Tom Attah, Joel Morris, Andy Murray, Brontë Schiltz and some other people I won't mention just yet to add a bit of suspense.

Toby Hadoke, is of course, an authority on all things Nigel Kneale and Quatermass and I'm looking forward to his imminent book.

Friday, March 28, 2025

Cinema Limbo: Observe and Report

Monday, March 10, 2025

Terror of the Suburbs, with Matthew Sweet

|

| Director Jon Clarke and camera op Lewis Hobson on Ealing High Street where Autons once invaded |

|

| Presenter Matthew Sweet on the corner of Ealing Broadway and Ealing High Street, outside the Autons' favourite branch of M&S |

|

| Jon and Lewis line up a shot with Matthew |

|

| Lewis, Jon, expert guest Alex Moore, Matthew Sweet and me (Photo by Kitty Dunning) |

|

| Me looming in the foreground while the team interview Dr Adam Scovell outside Ealing Film Studios |

|

| Dr Adam Scovell and Matthew Sweet at Ealing Film Studios |

|

| Nice Vibez, Lime Grove |

|

| Jon records Subhadra Das and Matthew Sweet in Chiswick |

|

| Subhadra and Matthew in Chiswick |

|

| Jon records Matthew's reaction shot in front of a brick wall |

|

| Matthew and Jon in front of the Palace of Westminster, the south side of the river popular with alien invasions |

|

| Matthew and Dr Rupa Huq, MP at Portcullis House |

|

| Jon and Matthew in front of Elizabeth Tower |

Thursday, February 13, 2025

A Masterpiece in Disarray - David Lynch's Dune an Oral History, by Max Evry

I started the book that afternoon but, like the film (and the novel it’s based on), it’s a vast sprawling epic and has taken a while to get through, not least because I’ve had a whole bunch of work stuff going on, too. Evry tells us at the start that he ordered the wealth of information so that we can skip to the bits of interest, whether that’s his detailed histories of pre-production, filming and what happened afterwards, the huge oral history of interviews with cast and crew, or the extra stuff like the merchandise and legacy of this peculiar, beguiling movie. I am hardcore and did the whole lot.

At first, I thought the book might have been better edited, even judiciously pruned, as there’s quite a lot of repetition. But as I read, on the repetition became important to our understanding: these are things on which people agree, in contrast to the many points on which there is less consensus.

Some witnesses, such as costume designer Bob Ringwood, are engagingly gossipy and forthright in their views. Others are more cautious in what they share. That is especially telling when their accounts are combined. For example, there’s the account of one male actor getting into character on set by shouting at and upsetting co-star Francesca Annis. Annis, cited in a contemporary interview (she did not contribute to this new book) declines to name the male actor. But here, publicity executive Paul M Sammon does (p. 223).

This is immediately followed by a contribution from another cast member, Sean Young, who doesn’t name the male actor or refer to the incident specifically. Yet by placing her words directly after Sammon, the implication is that she’s telling us what happened in response on set.

“As an actor, when I’m working with other actors, we all know who’s the deadwood. We all know who it is. We may not say it, but we’ll avoid them.” (p. 224)

There’s loads I found fascinating here. Val Kilmer and Tom Cruise screen-tested for the lead role of Paul. MacLachlan walked off set several weeks into filming because he’d still not received a contract. The rubberised stillsuits created for Dune were a big influence on Michael Keaton’s costume as Batman — also realised by Bob Ringwood — and superhero costumes ever since. Production on Dune overlapped a bit with Conan the Destroyer, using some of the same locations and sets, and at one point you could see both out in the desert on facing dunes. There’s stuff on the music and marketing and merchandise… There is a lot of detail.

These details could have been summarised or more concisely related but that would be missing a big part of the appeal of this book. A bit like the documentary Get Back where we sit day after day with the Beatles, the joy here is all the mundane, ordinary stuff as well. It’s the granular detail that really opens up the creative process. We gain a strong sense of what Lynch was doing, what he tried to achieve and what exactly went wrong.

A few days after receiving the book, I watched the movie with my teenage son, who had seen the Villeneuve Dune and Dune: Part II but came to this old film wholly new. He enjoyed it, I think, and found it interesting to see a different take on the same material, but his main issue was that the last hour or so is too rushed, too much happening too quickly for it to have an emotional impact. That, I now learn from reading this book, is because the production shot largely in script order; when money began to run out, they ripped our whole pages of what they still had to shoot…

Insights into the production and thus what we see on screen only take up the first half of this enormous volume. Evry has just as much interest in what followed, picking over the way the film was released, seen and received. More than that, there’s the sense of how it has haunted (or not) the people who made it.

Now, this is an oral history — it says as such on the cover — and memory can be a bit fallible. Evry does a good job in outlining the history as he understands it and then letting the people involved have their say, whether or not that contradicts the “facts” or other contributors. I think sometimes what people say could do with a little more interrogation. For example, we learn how one particular design was inspired by a trip Lynch made as the guest of producer Raffaella De Laurentiis and her movie mogul father Dino. But we’re told that,“Dino took him [Lynch] and Raffaella on an impromptu (and speedy) car trip to Venice, arriving directly in St Mark’s Square.” (p. 61).

That’s not technically possible given how Venice doesn’t have roads. Besides, Bob Ringwood then tells us that they all arrived by plane (p. 111).

Since I’m quibbling over small stuff (minuscule!), we’re frequently told of scenes being “lensed” or hear of “lensing” as a synonym for shooting. I don’t think that’s ever in a quotation from cast or crew; it’s a term used by movie journalists rather than those who make movies, not least because you fix or modify a “lens” before you start the action. Referring to Lynch as “the helmer” rather than director is another journalistic cliché, and not quite appropriate in this case since a key element of the story is how Lynch wasn’t in overall charge of what made it to the screen.

At times, the prose is oddly colloquial, too. When discussing the possibility of a director’s cut of the movie, we’re told that Lynch was “initially enthusiastic about taking a mulligan”, which I had to look up (it means when a golfer is allowed to replay a stroke), and then that “the studio refused to pony up the right amount of dough” (both quotations, p. 293). That is quite the mixed metaphor.

I raise this because the book is otherwise so often very good at explaining simply and clearly what were very technical procedures, such as the way the film was financed or the then-pioneering special effects. It makes us understand exactly how ingenious and revolutionary a lot of this stuff was for it’s time, as well as how influential. But also I am a jaded old hack who finds such grammatical stuff distracting and what I really want — in this book, in the film — is to lose myself in the weird, rich world of Dune.

Pedantic quibbling aside, this is an extraordinary, rich and insightful book. I’m tantalised by the details that remain elusive: how much footage actually survives; how possible it would be, with some new effects work, to produce a director’s cut, and how much of a screenplay for Dune II Lynch may have written.

The book ends with a short, sweet interview with Lynch himself, who just wants to say how much he enjoyed working with cast and crew for all he doesn’t much rate the film. My sense is of Evry trying valiantly to keep the call going, to draw more from Lynch and to somehow articulate something of what Dune means to him, the author of this exhaustive book. “Fantastic, man,” says Lynch, cheerily, and ends the conversation.

We’re left hanging. Now we always will be.

See also:

Saturday, August 24, 2024

The DNA of Doctor Who - The Philip Hinchcliffe Years

The obvious influence, of course, is the 1956 movie Forbidden Planet, which the BBC broadcast at 6.35 pm on Wednesday 6 November 1974 - just right to inspire the development of the Doctor Who stories that became Planet of Evil and The Brain of Morbius. I dig into that and also how the same film influenced early Doctor Who as well as other sci-fi such as Star Trek (citing the excellent ‘Gene Roddenberry’s Cinematic Influences’ by Michael Kmet from 2013) and Star Wars (see the 2012 Wired interview, ‘Ben Burtt on Star Wars, Forbidden Planet and the Sound of Sci-Fi’ y Geeta Dayal).

Hinchcliffe says on the documentary made for the DVD release of Planet of Evil (by my friend Ed Stradling) that he suggested the ‘flying eye’ drone seen in the story, having read of something similar in a science-fiction story at the time. The Dictionary of Surveillance Terms in Science Fiction at the Technovelgy site helped me suggest some candidates for that story.

I also mention Isaac Asimov’s own timeline-of-the-future for his various short stories and novels, which I drew from ‘A page from Isaac Asimov’s notebook’, Thrilling Wonder Stories, vol. 44 #3 (Winter 1955), p. 63.

Edited by Gary Russell and published by Gareth Kavanagh at Roundel Books, you can buy The DNA of Doctor Who - The Philip Hinchcliffe Years from the Cutaway Comics site.

Sunday, March 17, 2024

Dune Part Two

The thing that really strikes me is what a sensory film this is, the bass continually rumbling our seats and muscles, and then lots of tingling ASMR. That's all in tune with the wonders seen on screen, everything ever more epic. Combined, this is a feast for the senses, a film you less see as feel. The plot is also continually intriguing, and the result, a bit to my surprise, captivated his lordship for pretty much the almost three-hour run.

The serious tone of it all makes it easy to mock - some have pointed out that the plot if basically, "He's not the messiah, he's a very naughty boy", set on a planet of cocaine. The Lord of Chaos was also tickled by Kieran Hodgson's bad movie impressions.

True, the villains are all a bit straightforwardly wicked - black-and-white characters from a black-and-white world. Where the film really works, I think, is in the nuance elsewhere: different factions within the Fremen, the Bene Gesserit endeavouring to play all sides at once, and a sense of complexity and richness in the peoples depicted that meant, even though I know the novel, I wasn't quite sure how it would all turn out.

Some notable things in the book (and 1984 version of the film) are not included here, and I wonder if those will feature in Part Three - and so won't spoil them here. I'll also be interested to see if a further instalment still feels like Dune if set more extensively on other worlds.

Sunday, March 10, 2024

Star Wars Memories, by Craig Miller

|

"Another thing about the Kenner deal was that it included in the agreement that as long as Kenner paid a minimum royalty of $100,000 a year, they would be able to keep the licence for Star Wars toys for as long as they wanted. [But in the late 80s/early 90s] there hadn't been any Star Wars movies for a while and it didn't look like there would ever be. So [some executive] stopped paying the royalty. And the licence reverted to Lucasfilm." (p. 54)

"The new deal for the master toy licence for Star Wars ended up costing Hasbro close to a billion dollars in cash and stock." (p. 55)

It's interesting, too, to see the efforts made to ensure Star Wars characters remained in character even when appearing on Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, such as vetoing the request to have R2D2 sing a version of the ABC because the droid doesn't speak English.

There's lots on fan culture, conventions and activities of the period, and the differences between the US and UK. Craig has to explain to his US readers what he means by Blu Tack (p. 292), while staff in UK hotels in 1979 were repeatedly foxed by requests for ice coffee (p. 299), providing hot coffee served with either ice or ice cream. Towards the end, Craig lists contemporary reviews and criticisms of The Empire Strikes Back - that stuff isn't explained, that it's too jokey, or otherwise not true enough to what's gone before - that have continued to be made of new Star Wars films ever since.

On p. 392 he points out an amazing detail in The Empire Strikes Back which, despite having seen the film a thousand times, I'd never noticed before. But he also raises a question which I think I might be able to answer. On pp. 401-403, he puzzles over the appeal of characters such as Boba Fett, Darth Maul and Captain Phasma when we learn so little about them in the films. As he says, they look pretty cool but I think it's also important that they're blank slates. As well as how little we learn about their stories, two of them are masked and one is heavily made up, which adds to their mystery. They are characters on whom we as viewers can project. That absence of explanation invites us to imagine their stories, their lives - so they offer us a way in to this universe.

In fact, that kind of participation is what this book covers so well. I've read lots of other things about the making of Star Wars, focused on cast and crew. Craig's book is about how the production team actively engaged with and encouraged fans to take Star Wars to their hearts and into their lives. There's lots to learn from here. And lots to be grateful for.

Thursday, February 08, 2024

Cinema Limbo: The Last Wave

First, I thought I knew Peter Weir's work pretty well but have never heard of this odd, early film.

Secondly, watching it really helped bring together lots of my thinking about the context in which it was made and efforts to combat the 'cultural cringe' in Australia, which I detail in my book on David Whitaker.

You can also listen to the previous episodes I've been on:

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

Love and Let Die, by John Higgs

"That's as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs," quips Sean Connery's Bond in Goldfinger (1964), a moment before someone hits him. Yet less than a decade later, ex-Beatle Paul McCartney and ex-Beatles producer George Martin provided the soundtrack for Bond movie Live and Let Die (1973). I've long thought this was evidence of seismic shifts in contemporary culture over a very brief period, but not got much further that that. This is the territory Higgs dives into in his book, with lots of fresh insight and stuff I didn't know, for all that the subjects are so familiar.

How strange to realise that I've been part of these historical changes. I was at university in the mid-1990s when the Beatles enjoyed a resurgence in things like the Anthology TV series, and well remember debates had then about who was best: the Beatles or the Stones. How disquieting to realise, as Higgs says, that we don't make that comparison any more, without ever being aware of a moment when things changed.

Higgs is also of his (and our) time in rejecting ideas that I can remember used to hold considerable sway, such as that John Lennon was the 'best' Beatle, or the band's driving creative force. As the book says, there's growing recognition of what the four Beatles accomplished together rather than as competing individuals. There's something of this, too, in the way Higgs positions Bond to the Beatles. Initially, they're binary opposites, Bond an establishment figure Higgs equates with death, the Beatles working-class rebels all about life and love. By the end, it's as if they synchronise.

This might all sound a bit highfalutin but the insights here are smart and funny. As just one example, here's what Bond's favourite drink reveals about who he is.

"Bond's belief that he knows exactly what the best is appears early in the first novel Casino Royale, when he goes to the bar and orders a dry martini in a deep champagne goblet. Not trusting the barman to know how to make a martini, he gives him specific instructions. 'Three measures of Gordon's, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it's ice cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon-peel.' When the drink arrives, he tells that barman that is is 'Excellent,' then adds, 'But if you can get a vodka made with grain instead of potatoes, you will find it still better.' Most people who have worked in the service industries will recognise a customer like this." (pp. 242-3)

Amazing - Bond as an umarell!

I especially like how free-wheeling and broad this all is. There's stuff on shamanic ceremonies from the ancient past, stuff on Freud and the fine art world and Putin. At one point, Higgs talks about the damaging effects of fame in disconnecting a rock star (or anyone else famous) from everyone else.

"Drugs and alcohol appear to mask this disconnect, but in reality, they exaggerate it - cocaine in particular acts as fascism in powdered form. It erodes empathy and keeps the focus on the ever-hardening ego." (p. 294)

It probes the less palatable bits of popular history, grappling head on the complexities of our heroes' objectionable behaviour and views. Our heroes are not always good people, yet by framing this all as a study of how attitudes and culture have shifted, the book avoids making them all villains.

I nodded along to lots of perceptive stuff, like the thoughts on why Spectre (2016) didn't work precisely because it used screenwriting structures that usually do well in other movies. But I'm not sure Higgs is always right. He argues that a derisive response to a particular CGI sequence in Die Another Day (2002) led to a serious rethink by the Bond producers, which included sacking Pierce Brosnan. I suspect a more pertinent reason was that - as I understand it - Brosnan injured his knee while filming the hovercraft chase and first unit production had to be postponed while he underwent surgery. That would have been expensive and an ongoing risk for an ongoing series of action movies. The fantasy of a Bond who is, over 60 years of movies, always in his prime, must square up against the practicalities of ageing. And that's in line with what Higgs argues elsewhere.

But I don't make this point to criticise. It's more that I found myself responding to the book as if it were a conversation, inviting the reader to engage - and argue. Most potent of all is the final chapter. Having delved so deeply into the past, the author maps out how Bond should develop from here. Yes, absolutely, a younger, millennial Bond who'll appeal to a new generation, and one big on fun and consent, and whose partners don't all die. But also -

[Thankfully, Simon is dragged off-stage.]

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

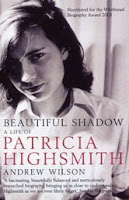

Beautiful Shadow - A Life of Patricia Highsmith, by Andrew Wilson

It's a fascinating story of a fascinating life. Highsmith is a complex, contradictory subject - on several occasions we're given completely different accounts of her, by turns cruel or kind, quiet or outspoken, fearful or bold. There are lots of reasons not to like her - the racism, the snobbery, the meanness with money when she was so wealthy. Yet understanding her background, her relationship (or lack of it) with her mother and her various struggles and heartbreaks makes this a compelling read.

There are all kinds of odd, striking moments. As well as the snails, there's her short-lived relationship with Tabea Blumenschein,

"the 25 year-old star and producer of the lesbian avant-garde pirate adventure Madame X" (p. 366).

Highsmith and Blumenschein spent six days together in a flat in Pelham Crescent, South Kensington, in May 1978 and at one point browsed the record shops. Blumenschein told Wilson that,

"Pat bought me the Stiff Little Fingers record" (p. 367),

presumably the band's debut single "Suspect Device" (released 4 February that year), before they went to dine with Arthur Koestler. The incongruity of that is even more striking when compared to Highsmith's selection the following year for Desert Island Discs: Bach (twice), Mahler and Mozart, and George Shearing's "Lullaby of Birdland".

A number of things made me begin to suspect that Highsmith was neurodiverse, and late on in the book her friend and neighbour Vivien De Bernardi told Wilson,

"In hindsight, I think Pat could have had a form of high-functioning Asperger's Syndrome. She had a lot of typical traits. She had a terrible sense of direction ... She was hypersensitive to sound and had these communication difficulties. Most of us screen certain things, but she would spit out everything she thought. She was not aware of the nuances of conversation and she didn't realise when she had hurt other people," (p. 394).

De Bernardi said this explains why Highsmith's relationships did not last; I think that's a bit glib - and that Highsmith may also have had some kind of attachment disorder, not helped by her (lack of) relationship with her mother. But I'm struck by De Bernardi's perspective of how this neurodiversity impacted Highsmith the writer:

"Although she didn't really understand other people - she had such a strange interior world - she was a fantastic observer. She would see things that an average person would never experience," (ibid).

Wilson has much to say about the content of and responses to Highsmith's lesbian novel The Price of Salt (1952), later republished as Carol and adapted into the acclaimed film. Highsmith originally published the book under a pseudonym and even when it went out in her own name was guarded in interviews about her sexuality. Often, people who knew Highsmith speak of her attitude to women as if from an outside perspective - as if she were a man. Wilson quotes Highsmith's own cahiers (notebooks) at great length, including a passage from 1942 that is ostensibly about other women and yet surely about herself.

"The Lesbian, the classic Lesbian, never seeks her equal. She is ... the soi-disant [self-styled] male, who does not expect his match in his mate, who would rather use her as the base-on-the-earth which he can never be," (p. 48, quoting Highsmith's Cahier 8, 11/18/42, Swiss Literary Archives in Berne).

Repeatedly, Highsmith identified with her most famous fictional creation Tom Ripley, signing a copy of Ripley Under Ground for her friend Charles Latimer as "from Tom (Pat)," (p. 194, but see pp. 194-6, 199, 350 and 454 for further examples). I now want to reread The Talented Mr Ripley (1955) with all this stuff in mind - from a queer (in the sense of both "strange" and "homosexual"), autistic, trans perspective. It's a book about somebody wanting to be and transforming themselves into someone else; an act of disguise that I think, having read this biography, might be very revealing.

Wednesday, January 04, 2023

Adventures in the Screen Trade, by William Goldman

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Cinema Limbo: Give My Regards to Broad Street

Saturday, December 03, 2022

Charles Hawtrey 1914-1988 The Man Who Was Private Widdle, by Roger Lewis

“pampered with port-soaked sugar lumps, its bread and butter sprinkled with Cyprus sherry, [and] used to walk into doors and see double when chasing mice.” (pp. 70-71)

This is just one extraordinary, sad and savage anecdote in Roger Lewis's pithy biography. Lewis has been diligent in going through BBC and BFI paperwork and in talking to those who knew Hawtrey in person. As well as the cast and crew of various productions, Lewis spoke to cab drivers, publicans, neighbours, and is good on the gulf between the cheery, cheeky persona captured on film and the angry, lecherous drunk of real life.

Hawtrey's meanness is quite something:

“Of necessity [Lewis claims] he was frugal, penny-pinching. He maintained his account at the Royal Bank of Scotland (Piccadilly branch), because he believed the Scots would keep a beadier eye on their customers’ shillings. He’d lug bags of carrots from Leeds to Kent, because vegetables were cheaper in Yorkshire. He pilfered toilet rolls from public lavatories — or at least his mother did. She was notorious for wiping out supplies at Pinewood and, when rumbled, tried to flush away the incriminating evidence, which blocked the drains, closing down production on Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Hawtrey was told that in future his mother would have to be locked in his dressing room.” (p. 72)

That's a fantastic a story but I'm not sure it can be true as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang began filming in June 1967 and Wikipedia claims that Hawtrey's mum Alice died in 1965. Lewis doesn't provide a source.

There's lots on money here. Hawtrey and his costars did not get rich from the Carry On films but producer Peter Rogers did. Instead, Hawtrey converted his house in Kew into bedsits — though implied to Roy Castle while making Carry on Up the Khyber in 1968 that he owned a “block of flats”. But Lewis says this enterprise didn't work out, and Hawtrey ended up being “ripped off” (p. 89). He retired to Deal, got banned from all its pubs and finally collapsed in a hotel doorway.

It's a troubled end to a troubled career. Hawtrey “never mixed with the rich and famous” (p. 12), and yet and some notable early roles. As well as playing several women on stage, he understudied Robert Helpmann as Gremio in Tyrone Guthrie’s production of The Merchant of Venice at the Old Vic, the cast including Roger Livsey as Petruchio and, in a small part, the future novelist Robertson Davies. A couple of years later, Hawtrey was in the cast of New Faces, the show that debuted Eric Maschwitz's hit song, “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.”

But Lewis shares excerpts over three pages from polite, curt rejections from the 1940s and 50s. Then, on page 61, he gives a long list of names at the BBC that Hawtrey wrote to in radio and TV, but concludes that these were,

“all radio or television apparatchiks, and not a single one of these names rings any bells with me” (p. 61n).

In fact, the list includes television pioneer Rudolph Cartier, Cecil McGivern (Controller, then Deputy Director of Television) and Shaun Sutton (later Head of Drama). I recognised various jobbing staff directors from the drama department, and Graeme Muir from light entertainment. So Hawtrey wasn't just writing to “everybody at Broadcasting House, from the Director-General to the janitors”; this is evidence of his range and aspirations — a serious, dramatic actor as well as comic foil.

Friday, December 02, 2022

Clips from a Life, by Denis Norden

Before that, Whitaker was script editor for Light Entertainment at the BBC, at the same time that Denis Norden and Frank Muir were employed as advisers on comedy. Whitaker then succeeded Norden (and Hazel Adair) as chair of the guild. So I scoured this memoir for any telling detail.

As Norden admits, it's is a rather loose collection of memories, jotted down as they occurred to him and then assembled in rough chronological order. There's a lot on his love of puns and odd turns of phrase, and much of the history is given by anecdote. He doesn't mention Whitaker but provides some fun tales about people in the same orbit - Ted Ray, Eric Maschwitz, Ronnie Waldman, the sitcom Brothers in Law starring Richard Briers and June Barry (Whitaker's first wife), and the early days of the guild.

For example, there's the striking fact that Hazel Adair, co-creator of Compact and Crossroads, who was Norden's co-chair, “at the Guild’s first Awards Dinner opened the dancing with Lew Grade” (p. 281).

Norden's eye for comic detail means there's plenty of vivid, wry observations. I particularly liked this, on the cultures of cinema:

“During the early forties I did some RAF training in Blackpool, where I discovered the cinemas were in the habit of interrupting the main feature sharp at 4 pm every day, regardless of what point in the storyline had been reached, in order to serve afternoon tea. The houselights would go up and trays bearing cups of tea would be passed along the rows. After fifteen minutes, the lights would dim down again, the trays would be passed back and the film wold resume. Anyone unwise enough to be sitting at the end of a row at that point could be left holding stacks of trays and empty cups.” (p. 33)

Thursday, July 21, 2022

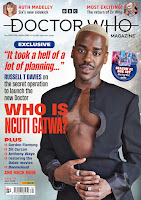

Doctor Who Magazine #580

The new issue of Doctor Who Magazine boasts a cover by Anthony Lamb showing the Daleks as they blaze into action. There's lots of coverage of the two Dalek movies from the 1960s - and of the never-made third movie, too. In "Mine Craft", me, Rhys Williams and Gavin Rymill detail - and reconstruct - the sets from the second Dalek movie.

(An odd thing to study the movie in such depth, and then go and see it on the big screen at Home in Manchester. I saw all sorts of details I'd never seen before, such as the glistening lava on the exploded Dalek castle at the end...)

There's also another "Sufficient Data" by me and Ben Morris, this time on distances Doctor Who has fallen.

Sunday, July 10, 2022

Once Upon a Galaxy: The Making of the Empire Strikes Back, by Alan Arnold

His detachment is quickly evident. The diary starts on 3 March 1979 with the crew struggling through a blizzard to reach Finze in Norway for the start of location shooting. Arnold mutters that in these treacherous conditions no one helped him unload the suitcases from the train, singling out Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker in the film) in particular.

"But [I] told myself without total conviction that Mark was probably more concerned about his [pregnant] wife." (p. 5)

Yes, that may have been on his mind.

Arnold details the problems faced by the production and the ingenious solutions: shooting key scenes in the snow just outside their hotel; getting Harrison Ford (Han Solo) to join them last-minute as the schedule is changed; the logistical response to mounting costs and delays.

There's plenty of great detail, not least because Arnold had access to the lead actors and a wide range of those on the crew. There's a good interview with the notoriously reticent Harrison Ford on page 24, though the actor later brushes off a second attempt. I didn't know that the film's Snowspeeders were designed by Ogle Design Ltd, "a company better known for its Reliant sports car (p. 39), and I like production designer Norman Reynolds' description of these new creations as flying "close to the surface like an airborne tank." (p. 43).

It's interesting to see how practicalities shaped things, and how very different Star Wars might have been: the carbon-freezing of Han Solo, described at times here as his "execution", covered the fact that Ford might not have featured in the third film. On 15 May 1979, well into production, producers George Lucas and Gary Kurtz take Sir Alec Guinness out to lunch to discuss whether he will participate in the film (p. 85), something still apparently in doubt until 5 September when he turns up for his single day (p. 240). At one point Lucas suggests the part might have been recast.

Arnold is a little pretentious at times, sharing a history of the medieval Mummers (p. 60), or likening new character Boba Fett to Shakespeare's Richard II (p. 67). But he's also got a good eye for the telling, incongruous moments.

"Of England it's alleged that everything there stops for tea, but this is not true in the film business. It is taken on the run, without interruption to the work continuing on the floor. Morning and afternoon, trolleys bearing urns of tea and coffee are wheeled onto the soundstages by ladies whom you suspect have spent the interim studying their horoscopes. They are actually immune to surprise, even when the lineup for tea includes, as it did today on the ice-cavern set [4 April], a platoon of snowtroopers in white armoured suits, a robot, Darth Vader, and the Wampa Ice Creature. The imperturbable tea ladies served them all with their characteristic cool, as calm as Everest explorers confronted by an abominable snowman. They know that anyone who enjoys a cup of tea can't be all that abominable." (p. 61)

There's an especially extraordinary sequence, pp. 128-147, in which Arnold has director Irvin Kershner miked up while shooting the pivotal scene of Han Solo's "execution" in the carbon-freezing chamber. He and Ford puzzle over dialogue and motivation, honing the words on the page into something really powerful. But Carrie Fisher (Princess Leia) then objects to getting these changes last minute, and from Ford rather than the director. She lashes out - literally slapping Billy Dee Williams (Lando Calrissian). And just as it's all kicking off, David Prowse (Darth Vader) tries to interest the director in his new book on keeping fit!

Fisher surely didn't approve the use of this in the book, or producer Gary Kurtz's comments that she "doesn't always look after herself as she should [and] doesn't pay sufficient attention to proper eating habits" (p. 123). Yet Arnold is also protective of the young actress, such as when she's subjected to a journalist who had got onto the set under false pretences - an experience Fisher describes as akin to a "rape" (p. 81). He's also sensitive to her skills as an actress, inspired by close study of old, silent films that focus on the close-up.

Arnold also reports a spat between Hamill and the director, soon after Hamill's baby son is born. At the time, the fractiousness is put down to Hamill having damaged his thumb (p. 150) which might mean the lightsaber battle that he has trained for will now be performed by a double. The sense is that neither Hamill nor Fisher had any say over this nakedly honest stuff being put in the book; the publicist who ought to have been protecting their interests was the one who wrote it. But later, Hamill at least gets to put this "terribly childish" disagreement in context.

"Our only real flare-up was on the carbon-freezing chamber set. Tempers were on edge anyway because it was like working in a sauna ... "Everybody felt guilty seconds later" (p. 213)

We finish with the film being edited, and Arnold getting lost on his way to the home of John Williams, who is busy composing the score. The book was published in August 1980 to coincide with the release of the film - so there was no way of knowing if all this work was going to pay off. Like the film itself, we leave on a cliffhanger.

Arnold concludes in philosophical mood about the creative arts in general, but more striking is what follows his words: credits listing all the many people involved in making the film.

See also:

Friday, May 27, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #578

Had it not been for this exciting announcement, the cover would probably have gone to Peter Cushing, star of the 1960s Dalek movies that are being re-released this summer. There is lots about the films this issue, including two things by me.

In "Sets and the City", Rhys Williams and Gav Rymill recreate the sets from the 1965 film Dr Who and the Daleks, with commentary by me and Rhys. This month's "Sufficient Data" infographic by me and Ben Morris charts actors from the first Dalek movie who were also in TV Doctor Who.

(By nice coincidence, almost exactly 20 years ago, my first ever work for DWM was a feature on that first Dalek movie and big-screen Doctor Who generally. That was a cover feature, too.)Plus, in "Hebe Monsters", I speak to Ruth Madeley about playing Hebe Harrison, new companion to the Sixth Doctor in his latest audio adventures.

Given all this, they've also put a photo of niceish me on page 3, taken by the Dr.

Thursday, December 09, 2021

James Bond in the Lancet

You need to be signed up to read the whole thing, but the teaser first paragraph goes like this:

"When actor Sean Connery died in October, 2020, media coverage focused on his success as the secret agent James Bond. The franchise is still going strong, with Bond now played by Daniel Craig and No Time To Die, the latest film, now in cinemas. That enduring appeal is partly due to the movies consciously keeping up with the times and reflecting contemporary trends. Yet Connery's Bond films are still screened on prime-time TV in the UK; remarkable, given that the first of them, Dr No, is nearly 60 years old and invidiously features White actors made up to look Asian. The best of Connery's Bond films, Goldfinger (1964), was even back in cinemas at the end of 2020. They are exciting movies, and sexy and fun, but their persistence is down to something more profound. The world of espionage portrayed by mid-20th century writers was deeply concerned with scientific and political issues concerning individuality, identity, and the human mind..."

.jpg)