Spent a long weekend in Thessaloniki (also known as Salonica) in northern Greece with the Dr and my parents. Traipsed through a fair few museums and old churches and ate a lot of nice food.

I managed the first 200 pages of Mark Mazower's Salonica, which is brilliantly rich and well researched but a bit heavy for holiday reading. He charts the complex, multi-ethnic history of the city under Ottoman rule, comparing the different customs, manners and superstitions:

"Holy water helped Christians, Bulgarians were fond of salt; others used the heads of small, salted fish mixed in water, while everyone believed in the power of spitting in the face of a pretty child."

He also speaks of the power of pentagrams to Muslims, "for keeping babies in good health", and on the next page,

"Against the fear of infertility, ill health, envy or bad luck, the barriers between faiths quickly crumbled."

Ibid., p. 86.

The Dr's chief interest was the classical history. The

Archaeological Museum has a new digitisation project,

Macedonia: From Fragment to Pixels, and we had fun spotting Gods in an interactive wordsearch and making information pop up on maps. We were also wowed by the

Myrtis exhibition, where different scientific methods help bring back to life a small girl who died in the 5th century BC.

Sadly, a lot of the main museum was closed while we were there, but what we did mooch round was beautifully displayed and interpreted. The Dr especially liked seeing a Roman-period dining table recreated 'live' from a contemporary illustration and using real artefacts.

The

Museum of Byzantine Culture was free and quick to look round, with some nicely displayed bits of fresco. We tried several attempts to get into the open-air Roman forum, but always managed to find it closed so took pictures from the edges.

On our second full day, the Dr expertly guided us out by bus to the bus station (always well out of town in Greek cities), and thence onto a bus to

Vergina and the tumulus tomb where Alexander the Great buried his dad, Phillip II. It took a bit of wandering through the drizzle to find, and then it didn't look much - a bit of grassy hillock.

But inside was something else entirely: the most amazing museum of all the spectacular riches discovered in the tombs, right next to the tomb doorways in situ. The low-light only enhanced the splendor of the gold, but it was the simple, practical and perfectly preserved cups and pots that impressed - it was hard to believe they were 250 let alone 2,500 years old.

The haul included organic relics - so rare in archaeology of this age. There was a purple cloth with gold thread design, carvings in wood and ivory.

The tomb doorway showed a rare example of ancient Greek fresco painting, showing a hunting scene. On the tops of the doors were still vivid, bright highlights of orange and blue - again, a small detail that makes this ancient, strange civilisation so tangible.

If there was one slight off note, it was the insistence of some of the labels to explain that the finds showed that this ancient civilisation was characteristially

Greek - a political claim as much to do with Macedonia's recent history as the past. The god-king buried here in such finery would have sat uncomfortably with the hellenic Spartans and Athenians - who so famously managed without monarchy. It was

telling, not showing, forcing an opinion rather than letting us interpret the facts.

But otherwise, it was an extraordinary place and we dawdled round at the end, not really wanting to leave. (It was also all a bit

The Daemons - an iconic image of Alexander even showed him with horns.)

The next day we tried

Pella, Phillip's capital city and the birthplace of Alexander. This time, our bus efforts were less successful. First we ended up in Giannitsa because our bus driver forgot to drop us off in the right place, despite the Dr asking him specifically beforehand and his nodding as she pointed at the word 'Pella' on our ticket. In Giannitsa he only shook his head - we should have called out to stop the bus when we wanted to get off, what with our psychic knowledge of Macedonia having not visited before, and ignoring the fact that (as we discovered on the bus back again) that he'd not taken the Pella road in the first place.

And we'd been watching very carefully, too - because all along the route there were impressive tumulus tombs in the otherwise flat plains of farmland, all of them cool and alluring, and none of them labelled in big letters so you could identify them from the road.

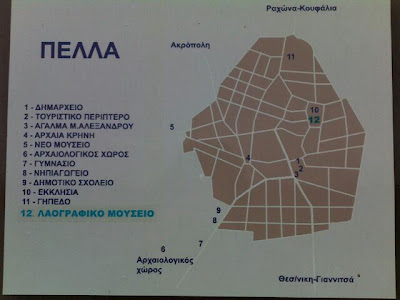

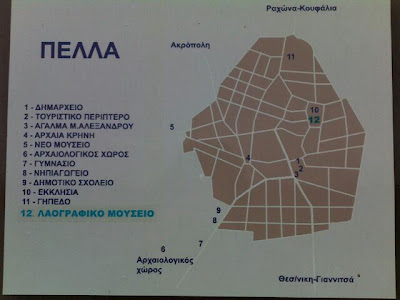

The bus back deposited us in the pouring rain at a lowly bus stop with a big sign declaring 'Pella' and a map of where things might be.

This solitary map was some way out of town, so we schlepped up through the lashing rain away from it and wandered round and round the town, stopping to take photos of our sodden holiday at the ankles of a big statue of Alexander.

At last, we discovered the new Archaeological Museums of Pella on the outskirts. A large sign outside explained the vast sum spent by the EU on the impressive new building - so new its

website is still under construction, though the place has been open since 2009. It seemed a lot of money for a place that had made it so hard to get to, and the small, narrow car park didn't exactly suggest it sees much traffic from cars and coaches. There were more staff than visitors, who followed us round like wardens, telling us we were allowed to take photos without a flash, and then telling us off if we did so.

Again, the actual artefacts were very impressive - some huge and well-preserved mosaics with lots of willy on show, all sorts of domestic and funerary bits and pieces that gave a glimpse of real people's lives. Photographs showed us just how far the archaeological site extended - the outline of a vast city still there because, after it was destroyed in an earthquake, the locals rebuilt their town further along the hill.

Again, the labels insisted that the dialects in the writing and the artistic styles linked these objects entirely and unquestionably to hellenic traditions, so that (the implication was ladled on) 2,500 years later Macedonia can't be anything other than Greek. I think you could probably make the same case for anywhere else Alexander conquered - Egypt, Iran or India.

There was no shop to buy books or postcards, and we could not visit any part of the huge archaeological site - which the old museum had been right in the heart of. It all felt a bit cold and unwelcoming for such a new and expensive place. We tramped back to the bus stop and sulked until a bus came.

Though it sometimes lacked in presentation, don't get me wrong: the sites and artefacts are amazing and it was mostly a great joy to plod about looking at stuff. The churches were all very welcoming, and often contained beautiful frescos. I felt a bit awkward being welcomed inside to look round during the middle of a service. Even when things were quiet, you feel a bit intrusive stood there gawping while devout local people slink to kiss the icons.

There were fun bits of Mediterranea, too, the little differences that remind you you're abroad. D gleefully ignored the no smoking signs in restaurants (one old chap in one restuarant at least made an effort to hide his fag below the edge of the table). The crossword and puzzle books on sale at all the kiosks had bikinied lovelies on their covers - what with that correlation between glamour* and wordsearches.

(* - that is, soft porn but with clothes on.)

The Greek alphabet also kept me childishly amused:

& Toot! - and with a cone of meat. And this logo for telecommunications was everywhere:

But the chief highlight was seeing the Dr relax, grinning round the museums and churches, not thinking about all the stressy house-buying stuff and, er, throwing herself into some shameless cat-adultery...