This mammoth, more-than-a-thousand-page account of broadcasting in the United Kingdom between 1955 and 1974 is the fifth and final volume in Asa Briggs’ definitive history largely focused on the BBC. ITV is included, but mostly in terms of its impact rather than in its own right.

Very quickly after launching in September 1955, ITV offered more hours of entertainment than the BBC. Advertising revenue also quickly made ITV very profitable - a one-shilling share in 1955 was worth £11 by 1958 (p. 11). With more money on offer, there was a huge flow of talent from the BBC; 500 out of 200 staff members moved to ITV in the first six months of 1956. The result was a desperate need for new people and a sharp rise in fees, doubling the cost of making an hour’s television (p. 18). Audiences responded to the fun, less formal ITV. The low point for the BBC came in the last quarter of 1957,

“when ITV, on the BBC’s own calculations, achieved a 72 per cent share of the viewing public wherever there was a choice.” (p. 20)

A lot of what follows is about the BBC’s concerted efforts to claw back that audience. But the book is as much about rivalry inside the BBC - the infighting of different departments, the effort to make the new BBC-2 different from and yet complementary to BBC-1, and the ascendance of TV over radio.

The latter happens gradually but with telling shifts. Since 1932, the monarch had addressed the nation each Christmas by radio; in 1957, Queen Elizabeth made the first such broadcast on TV (p. 144). That seems exactly on the cusp of the audience making the switch: in 1957 more radio-only licences were issued than radio-and-TV licences (7,558,843 to 6,966,256); in 1958 there were more TV-and-radio than radio-only licenses (8,090,003 to 6,556,347) (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). There’s a corresponding flip in the money spent on the two media: in 1957-8, expenditure on radio was more than on TV (£11,856,120 to £11,149,207); in 1958-9, more was spent on TV than radio (£13,988,812 to £11,441,818), and that gap only continued to widen (source: Appendix C, p. 1007). Yet aspects of BBC culture were slower to shift: Briggs notes that “The Governors … held most of their fortnightly meetings at Broadcasting House [home of radio] even after Television Centre was opened [in the summer of 1960]” (p. 32).

Television was expensive to buy into: the “cheapest Ferguson 17” television receiver” in an advertisement from 1957 “cost £72.9s, including purchase tax” (p. 5). Briggs compares the increased uptake of TV to the ownership of refrigerators and washing machines - 25% of households in 1955, 44% in 1960 - as well as cars (p. 6). So there was more going on that what’s often given as the reason TV caught on - ie the chance to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953. The sense is of new prosperity, or at least an end to post-war austerity. Television was part of a wider cultural movement. The total number of licences issued (radio and TV) rose steadily through the period covered, from 13.98 million in 1956 to 17.32 million in 1974 (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). By 1974, the Report of the Committee on Broadcasting Coverage chaired by Sir Stewart Crawford felt, according to Briggs, that,

“People now expected television services to be provided like electricity and water; they were ‘a condition of normal life’.” (p. 998)

This increase in viewers and therefore in licence fee revenue, plus the competition from ITV, led to a change in attitude at the BBC about the sort of thing they were doing. Briggs notes that the experimentalism of the early TV service gave way to more and more people speaking of “professionalism” - skill, experience and pride in the work being done (p. 24). I’m struck by how those skills was shared and developed:

“The Home Services, sound and television, gain … from the fact that they are part of an organisation of worldwide scope [with staff] freely transferred … from any one part of the corporation to another [meaning that Radio and TV had] a wide field of talent and experience to draw upon in filling their key positions”. (pp. 314-15)

There are numerous examples of this kind of cross-pollination. Police drama Dixon of Dock Green was produced by the Light Entertainment department. Innes Lloyd became producer of Doctor Who at the end of 1965 after years in Outside Broadcasts, which I think fed in to the contemporary feel he brought to the series, full of stylish location filming. Crews would work on drama, then the news, then Sportsview, flitting between genre and form. Briggs cites a particular example of this in two programmes initiated in 1957 following the end of the “toddlers’ truce”.

For years, television was required to stop broadcasting between 6 and 7 pm so that young children could be put to bed and older children could do their homework. But that meant a loss in advertising revenue at prime time, so the ITV companies appealed to Postmaster General Charles Hill, who was eventually persuaded to abolish the truce from February 1957. But what to put into that new slot?

“Both sides [ie BBC and ITV] recognised clearly that if viewers tuned into one particular channel in the early evening, there was considerable likelihood that they would stay with it for a large part of the evening that follows.” (Briggs, p. 160)

The BBC filled the new gap with two innovative programmes aimed at grabbing (and therefore holding) a very broad audience. From Monday to Friday, the slot was filled by Tonight, a current affairs programme that basically still survives today as The One Show. The fact that it remains such a staple of the TV landscape can hide how revolutionary it was:

“Through its magazine mix, which included music, Tonight deliberately blurred traditional distinctions between entertainment, information, and even education; while through its informal styles of presentation, it broke sharply with old BBC traditions of ‘correctness’ and ‘dignity’. It also showed the viewing public that the BBC could be just as sprightly and irreverent as ITV. Not surprisingly, therefore, the programme influenced many other programmes, including party political broadcasts.” (p. 162)

Briggs argues that part of the creative freedom came because Tonight was initially made outside the usual BBC studios and system, as space had been fully allocated while the truce was still in place. The programme was made in what became known as “Studio M”, in St Mary Abbots Place, Kensington. But the key thing is that this informality, the blurring of genre, spread.

“This [1960] was a time when old distinctions between drama and entertainment were themselves becoming at least as blurred as old distinctions between news and current affairs and entertainment.” (p. 195)

|

Jon Pertwee, Adam Faith

Six-Five Special (1958) |

On Saturdays, the same slot was filled by music show

Six-Five Special. Briggs says that this and

Grandstand (which began the following year in October 1958) were not the first programmes devoted to pop music or sport, but their under-rehearsed, spontaneous style was completely innovative (p. 200). Although

Six-Five Special had a special appeal to teen viewers, it and

Grandstand were, importantly, “not allowed to target one audience alone” (p. 199). With such broad, popular appeal,

“along with a number of other Saturday programmes, it [Six-Five Special] helped to reconstruct the British Saturday, which had, of course, begun to change in character long before the advent of competitive television [and was, with Grandstand, part of] a new leisure weekend.” (p. 199)

Elsewhere, Briggs notes the impact of TV - especially of ITV - on other forms of entertainment: attendance at football matches and cinemas dropped, with many cinemas closing (p. 185). Large audiences of varied ages were becoming glued to the box. I’d dare to suggest that this was not a “reconstruction” but the invention of Saturday, the later development of Juke Box Jury, Doctor Who, The Generation Game etc all part of a determined, conscious effort to compete with ITV with varied, engaging, good shows.

(On Sundays, the BBC continued to honour the truce, with no programming in the 6-7 slot that might compete with evening church services. From October 1961, the slot was taken by Songs of Praise.)

One key way of making good television was to write especially for the small screen. Briggs, of course, cites Nigel Kneale in this regard - though his The Quatermass Experiment and Nineteen Eight-Four are covered in Briggs’ previous volume. But Stuart Hood in A Survey of Television (1967) notes how sitcom grew out of the demands that TV placed on comedians:

"the medium is a voracious consumer of talent and turns. A comic who might in the [music or variety] halls hope to maintain himself with a polished routine changing little over the years, embellished a little, spiced with topicality, finds that his material is used up in the course of a couple of television appearances. The comic requires a team of writers to supply him with gags, and invention" (Hood, p. 152)

Briggs has more on this. For example, Eric Maschwitz, head of Light Entertainment at the BBC, remarked in 1960 that,

“We believe in comedy specially written for the television medium [and recognise] the great and essential value of writers, [employing] the best comedy writing teams [and] paying them, if necessary, as much as we pay the Stars they write for” (Briggs, p. 196-97)

Briggs makes the point on p. 210 that, “The fact that the scripts were written by named writers - and not by [anonymous] teams - distinguished British sitcom from that of the United States.” Some of these writers, such as Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, became household names. Frank Muir and Denis Norden appear, busy over scripts, in Richard Cawston’s documentary This is the BBC (1959, broadcast on TV in 1960): these are writers as film stars.

Hancock’s Half Hour (written by Galton and Simpson) and Whack-o (written by Muir and Norden) were, Briggs says, among the most popular TV programmes of the period, but he also explains how a technological innovation gave Hancock lasting power.

In August 1958, the BBC bought its first Ampex videotape recording machine. At £100 per tape, and with cut (ie edited) tapes not being reusable, this was an expensive system and most British television continued to be broadcast live and not saved for posterity. (Briggs explains, p. 836n, that Ampex was of more practical benefit in the US, where different time zones between the west and east coasts presented challenges for broadcast.)

From July 1959, Ampex was used to prerecord Hancock’s Half Hour, taking some of the pressure of live performance off its anxious star (p. 212). Producer Duncan Wood, who’d also overseen Six-Five Special, then made full use of Ampex to record Hancock’s Half-Hour out of chronological order,

“allowing for changes of scene and costume … Wood used great skill also in employing the camera in close-ups to register (and cut off at the right point) Hancock’s remarkable range of fascinating facial expressions … Galton and Simpson regarded the close-up as the ‘basis of television.’” (p. 213)

Prerecording allowed editing, which allowed better, more polished programmes. What’s more, prerecording meant Hancock’s Half-Hour could be - and was often - repeated, even after his death. The result was to score particular episodes and jokes - “That’s very nearly an armful” in The Blood Donor - into the cultural consciousness. Another, later comedy series, Dad’s Army, got higher viewing figures when it was repeated (p. 954).

|

Clive Dunn, Michael Bentine

It's a Square World (1963) |

Yet not all prerecorded shows survive or, even if they do, retain such cultural impact. I was fascinated to read Briggs on Michael Bentine’s

It’s a Square World (1960-64), which he wrote with John Law (most famous now for co-writing the “Class Sketch” with Marty Feldman). Some 46 of the 57 episodes of this pioneering series still exist, but there’s no DVD release and I don't think it's been repeated. A clip included on the DVD of

Doctor Who: The Aztecs gives a sense of the anarchic, richly inventive fun: Clive Dunn, dressed as Dr. Who, accidentally launches Television Centre into space, with commentary from Patrick Moore just like he’d give on

The Sky at Night. How I’d love to see the episode referred to by Briggs, where the Houses of Parliament are attacked by pirates and sink into the Thames, which caused trouble at the time of the 1964 general election...

Briggs says of the appeal of the later Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which he insists on referring to as “the Circus” rather than the more common “Python”) that,

“It took basic premises and reversed them. It’s humour, which was visual as much as verbal, again often succeeded in fusing both.” (p. 950)

More than that, it was comedy that spoofed and subverted the structures and furniture of television itself. In this, it surely owed a big debt to Bentine.

He’s not the only one to have been rather overlooked in histories of broadcasting. I’ve seen it said in many different places that Verity Lambert, first producer of Doctor Who, was also at the time,

“the BBC’s youngest, and only female, drama producer” (Archives Hub listing for the Verity Lambert papers)

Yet Briggs cites Dorothea Brooking and Joy Harington as producers of “memorable programmes” for the children’s department, referring to several dramas adapted from books. Harington had also produced adult drama - for example, she oversaw A Choice of Partners in June 1957, the first TV work by David Whitaker (whose career I am researching). In early 1963, “drama and light entertainment productions for children were removed from the Children’s Department,” says Briggs on page 179, with this responsibility going to the newly reorganised Drama and Light Entertainment departments respectively. Lambert may have been the only female producer in the Drama Department at the time she joined the BBC in June 1963. Except that Brooking produced an adaptation of Julius Caesar broadcast in November 1963, and Harington was still around; she produced drama-documentary Fothergale Co. Ltd, which began broadcast on 5 January 1965.

(Paddy Russell’s first credit as a producer was on The Massingham Affair, which began broadcast on 12 September 1964. Speaking of female producers, Briggs mentions Isa Benzie and Betty Rowley, the first two producers of the long-running Today programme on what’s now Radio 4 (p. 223). My sense is that there are many more women in key roles than this history implies.)

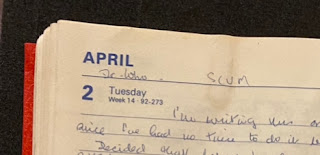

Stripped of responsibility for drama and light entertainment, the children’s department was incorporated into a new Family Programming group, headed by Doreen Stephens. According to Verity Lambert, this group was envious of Doctor Who - a programme they felt that they should be making. When, on 8 February 1964, an episode of Doctor Who showed teenage Susan Foreman attack a chair with some scissors, it was felt to break the BBC’s own code on acts of imitable violence. As Lambert told Doctor Who Magazine #235,

“The children’s department [ie Family Programming], who had been waiting patiently for something like this to happen, came down on us like a ton of bricks! We didn’t make the same mistake again.”

Lambert had to write Doreen Stephens an apology, so it’s interesting to read in Briggs that Stephens didn’t think violence on screen was necessarily bad. In a lecture of 19 October 1966, she spoke of “overcoming timidity” in making programmes, and believed that,

“violence and tension [don’t] necessarily harm a child in normal circumstances [while] in middle-class homes of the twenties and thirties, too many children were brought up in cushioned innocence … protected as much as possible from all harsh realities.” (Briggs, p. 347).

|

"Compulsive nonsense"

Doctor Who (1965) |

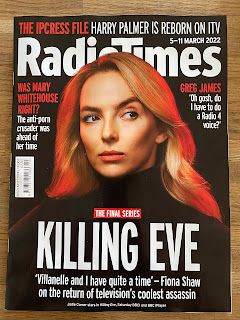

Briggs devotes a whole subsection to “New Programmes:

Dr Who and

Z Cars” (pp. 416-434), the complexities of creating and running

Doctor Who a good case study for understanding television more broadly. I'm acutely conscious in my work that the fact

Doctor Who is so long-running makes it an especially rich source text for social and cultural history, but Briggs is really concerned with explaining its early appeal.

“The university lecturer Edward Blishen called Doctor Who ‘compulsive nonsense’ [footnote: Daily Sketch, 3 July 1964, quoting a Report published by the Advisory Centre for Education], but there was often shrewd sense there as well. At its best it was capable of fascinating highly intelligent adults.” (p. 424)

Beyond the specific subsection, there are other insights into early Doctor Who, too. For example, Briggs tells us that,

“nearly 13 million BBC viewers had seen Colonel Glenn entering his capsule at Cape Canaveral before beginning his great orbital flight [as the first American in space, 20 February 1962]. An earlier report on the flight in Tonight had attracted the biggest audience hat the programme had ever achieved, nearly a third higher than the usual Thursday figure [footnote: BBC Record, 7 (March 1962): ‘Watching the Space Flight’’]” (p. 844)

Could this have inspired head of light entertainment (note - not drama) Eric Maschwitz to commission - via Donald Wilson of the Script Department - Alice Frick and Donald Bull to look into the potential for science-fiction on TV. Their report, delivered on 25 April that year, is the first document in the paper trail that leads to Doctor Who.

Then there is the impact of the programme once it was on air. On 16 September 1965, Prime Minister Harold Wilson addressed a dinner held at London’s Guildhall to mark ten years of the ITA - and of independent television. Part of Wilson’s speech mentioned programmes that he felt had made their mark. As well as Maigret, starring Wilson’s “old friend Rupert Davies”,

“It is a fact that Ena Sharples or Dr Finlay, Steptoe or Dr Who … have been seen by far more people than all the theatre audiences who ever saw all the actors that strode the stage in all the centuries between the first and second Elizabethan age.” (Copy of speech in R31/101/6, cited in Briggs, p. 497).

Two things about this seem extraordinary. One, Wilson - who was no fan of the BBC, as Briggs details at some length - quotes four BBC shows to one by ITV. And at the time, Doctor Who was not the institution it is now, a “heritage brand” of such recognised value that its next episode will be a major feature in the BBC's centenary celebrations this October. When Wilson spoke, this compulsive nonsense of a series was not quite two years-old.

But such is the power of television...

More by me on old telly: