There’s a fun moment in the Doctor Who story Dragonfire when the Seventh Doctor is required to distract a guard. Some other adventuring hero might cosh the guard on the head but the Doctor instead politely asks him about the nature of existence. The guard turns out to have strong opinions on the matter and the Doctor is soon out of his depth:

GUARD

You've no idea what a relief it is for me to have such a stimulating philosophical discussion — there are so few intellectuals about these days. Tell me, what do you think of the assertion that the semiotic thickness of a performed text varies according to the redundancy of auxiliary performance codes?

DOCTOR WHO

Yes.

Doctor Who and the Dragonfire by Ian Briggs (1987)

The question is drawn directly from an academic book on Doctor Who, in a section applying some ideas originated by Keir Elam — now professor of English literature at the University of Bologna.

“What Elam calls the semiotic ‘thickness’ (multiple codes) of a performed text varies according to the ‘redundancy’ (high predictability) of ‘auxiliary’ performance codes.”

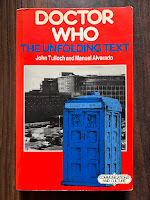

While this might at first seem impenetrable, authors John Tulloch and Manuel Alvarado immediately unpick its meaning.

“Thus, for instance, if the sets, music and so on were simply to reinforce the actors’ performance without adding to it or inflecting it in the direction of new associations, but simply overlaid the acted ‘pace’ and ‘drama’ with their own, they would be relatively redundant, serving only to bind together the text’s temporal unfolding. On the other hand, in the Williams/Adams story, City of Death, the use of music and sets in the scenes featuring the Count and Countess was more entropic, drawing on motifs which some audience members recognised as ‘very forties’, and therefore potentially relocating the stolen art theme in terms of, say, The Maltese Falcon.” (The Unfolding Text, p. 249)

In fact, the production of Dragonfire might have learned something from this and benefited from the same kind of added richness.

I’ve been busy over the past fortnight researching and writing a bunch of things and The Unfolding Text has been useful on more than one. First published in 1983 to coincide with Doctor Who’s 20th anniversary (so covering what’s now one-third of Doctor Who’s history), it was part of a “communications and culture” range published by Macmillan and executive edited by Stuart Hall and Paul Walton. Alongside The Unfolding Text were an academic study of James Bond and titles such as The Politics of Information, Culture and Control and Reproduction Ideologies.

My memory of the book, having read it while doing English Literary Studies at UCLAN in the last millennium, was that it’s heavy going, that sentence spoofed in Dragonfire representative of the whole. There’s certainly a lot of technical language but this time I found it all enjoyably gossipy.

The authors spoke to cast and crew from the past and then-present of Doctor Who, and attended rehearsals and recording of the 1982 story Kinda. Their media studies approach is quite different from the interviews published in fanzines, Doctor Who Magazine and other sources from the time, which tended to focus on what happened when, building up a timeline of production. Here, we get deeper insights into the thinking behind creative choices and a sense of what these mean. That’s especially revealing when people involved in making Doctor Who talk about stories they didn’t work on.

How fascinating, for example, to hear Douglas Adams — script editor on Doctor Who 1978-79 before becoming the best-selling author of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — explain why he didn’t like Logopolis (1981), written by his successor.

“In comparison to what we were doing, the new ones [episodes] are terribly, terribly slow. We seem to have endless, endless wanderings round and round the same point. I think that, in the time we were there, there was this sheer weight of ideas we managed to pack in — the sheer number of events and things going on … In contrast, in Logopolis we … did seem to spend ages and ages wandering around and around and around the interior of the TARDIS.” (pp. 219-220)

Then there’s where all this wandering led. Adams says he'd expended considerable energy in clarifying the “final threat” of any given story and “what the villain actually wants” (p. 170). He could see that reintroducing the Master — in the story preceding Logopolis — made plotting much simpler because he’s effectively the “guy in the black hat” and we can take for granted that he’s up to something bad.

“But to my mind that in the end means ‘boring’ because why does a guy want to take over the universe? … At the end of Logopolis suddenly you had the Master broadcasting a message to the entire universe, which to me just doesn’t mean anything. There’s nothing you can visualise there, and there’s nothing that actually has any meaning in any real world.” (p. 171)

Logopolis still haunts my imagination but it’s fascinating to hear Adams explain what he saw as fundamental shortcomings, the issue of tangibility illuminating his time on the series and the stories that followed. The sense is that, had he stayed in post, he wouldn’t have commissioned Logopolis. And he could critique the story because, even after leaving Doctor Who, he kept on watching and puzzling over how to make it work.

So, these interviews offer us authoritative insight into Doctor Who. Yet there’s something odd about the authority of this book. I’m especially conscious of this as the author of books and magazine articles about Doctor Who, and rereading The Unfolding Text has sparked a whole load of thoughts about my approach to authority.

For example, in citing Adams, the authors of The Unfolding Text repeatedly refer to him as “Doug”. How we refer to people has an impact on the way we perceive what they say. “Doug” is not Adams’s name professionally — he was always credited as “Douglas” — and I’d never heard him referred to “Doug” elsewhere. That suggested that the authors were on particularly close terms with Adams, which might then explain why he’d been so candid. My sense of the authors’ authority was coloured by the way they used his name.

But I checked with Kevin Davies, editor of last year’s best-selling 42: The Wildly Improbably Ideas of Douglas Adams, who’d known Adams very well. And he told me that, no, Douglas wasn’t “Doug":

“I think it’s safe to assume the Unfolding Text guys didn’t really know him.”

And that recolours my sense of authority here: if the authors got that wrong, what else might not be right?

While the authors clearly had access to production and many members of the cast and crew, they lacked access to archive materials more readily available now. That leads to some errors of fact.

“Though Donald Wilson, head of series/serials, also hated the [first] Dalek story, Lambert went ahead on the grounds that the next planned story, Marco Polo, was not ready.” (p. 42)

For one thing, Wilson was head of serials — there was a separate head of series at the time. For another, Lambert wouldn’t have considered replacing Marco Polo with the Dalek story. When it began, Doctor Who alternated historical stories with sci-fi, so you couldn’t swap one for the other. In fact, the first Dalek story was brought forward to replace a serial then called The Robots.

Besides, I think the above is cribbing from a mistaken belief among fans that two-part The Edge of Destruction was commissioned at late notice to fit between the Dalek story and Marco Polo because of delays on the latter. We now know from contemporary paperwork held in the BBC Written Archives Centre that that isn’t what happened at all — which I go into at inordinate length in my recent book for the Black Archive.

The most striking issue of access in The Unfolding Text is how little the authors have been able to see of old episodes on which to base their judgements. Chapter 1 devotes a lot of time to the very first 25-minute episode, An Unearthly Child (1963), and a similar level of depth is given in Chapter 6 to the Fifth Doctor story Kinda (1982). Coverage of the Fourth and Fifth Doctor’s eras is pretty wide-ranging, I suspect because it’s a recent memory for the authors and those they spoke to rather than that they went back and watched episodes anew. Discussion of the Second and Third Doctors’ eras is predominately focused on one story each, neither of them particularly representative of that period of Doctor Who. From the index:

‘Krotons, The’ 61, 69, 74-81, 91-7

‘Monster of Peladon, The’ 9, 52-4, 86-91, 106, 114, 182-3, 188, 224, 280

How different things are today, with almost all of Doctor Who up on iPlayer for researchers to research and for readers to check. It's also easier to check the correct titles of stories — The Unfolding Text refers to Masque of Mandragola and Castravalva on occasion, but also spells them correctly on others. And it attributes a line of dialogue to the wrong production team:

“With the exception of the Troughton era, Doctor Who has fundamentally adhered to the original brief of Verity Lambert and David Whittaker (sic) that the Doctor should appear as a ‘citizen of the universe and a gentleman to boot’.” (p. 100)

I don’t mean to nit-pick: it’s more that these things all illuminate something I’m very aware of at the moment — how access to old episodes is changing the ways that fans can and do engage with Doctor Who’s rich history. In what I write now, I can direct readers to watch episodes for themselves rather than spelling out what happens, and I can leave them to judge for themselves rather than offering an opinion. It’s a surrender or sharing of authority. But that also makes me realise how seldom The Unfolding Text provides synopses of the stories it mentions, given readers at the time were generally unable to see them again. We must take these authors on trust.

Some of the people interviewed hold pretty sexist views, not least on the role of the Doctor’s companions. This can be very revealing about what made it to the screen. Sometimes the authors also challenge the people interviewed but I think there’s a danger that things said by cast and crew then inform or even dictate the analysis.

For example, producer John Nathan Turner explains how the regular characters in the 1982 series were designed to appeal to a broad audience:

“We’ve got the young heroic Doctor who hopefully appeals to everyone, especially the ladies. We have a female companion called Tegan, who is 24, nice figure, nice legs who appeals to the men. And we have two young companions, Adric and Nyssa, who are both 18-19 and are there for audience identification — the younger audience.” (p. 207)

This is very different to what he inherited a year before from Douglas Adams and producer Graham Williams. Indeed, Nathan Turner thought that the mature, knowledgeable line-up of the Fourth Doctor, Romana and K-9 was “ludicrous”.

“There was no reason for the Doctor ever to have to explain anything to Romana. So that all conversation between them either became very bitchy to impart the plot, or else it was an unreasonable scene where the Doctor has to say, ‘Well, there’s part of your education that you don’t know about, and here it is…’” (p. 217)

When, exactly, is Romana “bitchy”? With episodes now readily available, we can go look for ourselves. Without them, we can only go on Nathan Turner’s say-so.

To be fair, the authors dig into these claims a bit, citing his “nice figure, nice legs” comment twice on the same page before asking him if there had been only tokenistic development of female companions.

“I don’t think it’s tokenism. Certainly the feminists would like Tegan. It just makes for greater drama between your regulars if you’ve got an aggressive girl who tends to think she knows best. It’s not tokenism in any way. It just makes for a better line-up if there is friction.” (p. 218)

But that doesn’t really square with what he said before, which the authors don't really address. Worse, I think, is that The Unfolding Text pursues a line of analysis directed by what they’ve been told and the terminology used.

“In … his second season, Nathan-Turner also reintroduced the 1963 element of Doctor and companions who don’t always ‘get on with one another’ but — very consciously — for ‘character’ rather than ‘bitchy’ reasons. … As with Barbara and Ian [in the 1960s], Tegan’s ‘bitching’ relationship with the Doctor was generated by his inability to return her [home].” (p. 217)

Even in quotations, it’s deploying “bitchy” as objective rather than objectionable. Do Barbara and Ian have a “bitching” relationship with the Doctor? How does the “friction” generated by “aggressive” Tegan differ from the “bitchy” Romana? Is that really the word to use? Go watch those episodes again and I think the answers are no, no and no.