I’m struggling a bit with prose for grown-ups, so over the last month worked my way through The Adventures of Tintin, an eight-volume box-set of the boy reporter’s collected scrapes, including the early, rough Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and the unfinished Tintin and the Alph-Art but not including the especially racist and colonialist Tintin in the Congo from which even Herge distanced himself. (The book is available to buy separately.)

My parents still have a bunch of Tintin books that I shared with my brothers. In my head they were always more my younger brother’s but I’m surprised now to discover how few of them I’d read. Running gags, such as the telephone being put through to the butcher, or insurance salesman Jolyon Wagg outstaying his welcome, seemed completely new.

I was also surprised by how funny so much of it is, having thought of Tintin as the po-faced cousin of Asterix, to whom I was devoted. But there’s loads of often very funny slapstick here, whole sequences of panels passing without a word. I wonder what it owes to the comedy of silent film.

The pace is also striking. Written as a newspaper strip but reformatted for book versions, each story licks along at great speed, full of incident and twists. There are plenty of cliffhangers - though, as with so many adventure serials, many of them are undone by outrageous good fortune or sleight of hand on the part of the author. Still, it’s exciting and fun.

And it looks beautiful. Herge's clean line style with no shading and flat colours means that strips that are nearly 100 years old reproduce nicely, and look fantastic on shiny, good quality paper. The style suggests cartoon-faced people in an otherwise convincingly realised world - it's both daft comic strip and gritty realism at the same time.

But also striking is the racist stuff. Even without Tintin in the Congo, there are plenty of crude racial and cultural stereotypes, perhaps the most jaw-dropping in The Broken Ear when Tintin blacks up.

Having nominally bought the collection for my nine year-old son, I started to have second thoughts - and I’m not the only one. On 10 June, just as I was reading this, Amol Rajan was on BBC News to talk about Gone With the Wind being removed from Netflix - just a day after he’d been on to talk about the more recent comedy Little Britain coming down from iPlayer.

“That is fraught with difficulty. Where does it stop? I'm reading Tintin with my son at the moment and an exhibition of tolerance it certainly is not. It reads like one long parade of racial cliches.” (Tweet by Amol Rajan, 10 June 2020)

He’s right, and there’s plenty here that made me uncomfortable - not least in those books that I'd read before without noticing this aspect. How strange, too, for a series of adventures for children to feature opium dens, slavery, alcoholism, kidnap and murder. I think Herge’s clean lines and flat colours, plus the slapstick stuff, are deceptive: Tintin’s a noble character in a world that is corrupt and cruel and dangerous.

Without wishing to excuse or downplay the racist depictions here, there’s clearly also an attempt to offer more nuance and counterpoint, such as in this sequence from The Blue Lotus where Tintin and his friend Chang try to dispel a few cultural myths.

I wonder how much of this is later revisionism. There’s clearly some of that going on. The jump in style between Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and the next book, Tintin in America, is so marked because the latter was redrawn. There’s evidence, too, that the revised books weren’t published in their original order. In Cigars of the Pharaohs, in volume 2 of this collection, Tintin is recognised because someone has a copy of Destination Moon, which is in volume 6.

(This also suggests that Tintin is a celebrity because of his adventures, and the accounts of them exist in his own world as colourful comic books, too.)

My guess is that this moment in King Ottaker’s Sceptre is also a later edit, perhaps after someone wrote in:

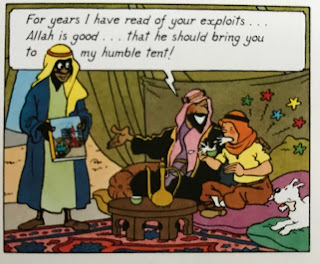

Anyway. There’s a notable shift in gear with The Crab With the Golden Claws, which feels more mature and better plotted, and introduces us to the brilliant Captain Archibald Haddock, a drunk old sea-dog with a heart of gold. Part of what makes this story feel epic is where it breaks the newspaper-strip format, with full and half-page panels. When these happen out in the desert, the effect is like suddenly going widescreen, the adventures directed by David Lean. Again, it’s a story about drug-smuggling and there are racial caricatures, but Tintin solves the mystery using pluck and intelligence rather than good fortune.

After the disappointing The Shooting Star (an odd one about an alien island that produces huge mushrooms), we’re onto what’s surely the classic pairing - The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham’s Treasure. I knew this one well and it’s a really good mystery, greatly helped by the focus on Captain Haddock. In Secret, we’re told the year is 1958 which came as a bit of a shock reading the adventures in sequence. Some 30 years have passed since Land of the Soviets and Tintin and his dog have not aged a day. It turns out that the original version of the strip was published between June 1942 and January 1943, so this is again another revision for the collected version. More than that, the stories have existed in a kind of timeless state. While Tintin in America mentioned Al Capone by name, we’ve had little sense of the real world. There has been no mention of the Second World War, the occupation of Tintin's native Belgium or that anything might have changed. I’ve since looked this up and see that The Crab With the Golden Claws was the first that Herge wrote while under occupation, and it’s tempting to try and see the gear-shift in the storytelling as some kind of response to real-world events. I’m not sure, but would like to know more.

Secret ends with Tintin directly addressing the reader to say the story is continued. Red Rackham’s Treasure begins with various suitors claiming to be descendants of the notorious pirate to get in on the treasure hunt. One of these, apparently as a sight gag, is a black man with very dark skin and big lips - so this kind of racist caricature isn’t only part of the early days of the series. On page 186 of my edition, we’re given the date Wednesday 23 July, suggesting this is still 1958.

There’s more continuity cock-up in The Seven Crystal Balls where we’re told of Bianca Castafiore that,

“she turns up in the oddest places: Syldavia, Borduria, the Red Sea… She seems to follows us around!” (p. 13)

But this is only the second time we’ve met her, and The Red Sea Sharks is in six books’ time. On the next page, General Alcazar seems to have met Haddock before, but Haddock wasn’t in that previous adventure at all. Land of Black Gold then features two more characters returning from previous books, and depends on a lot of coincidence. The books keep finding dramatic new locations round the world, but feel increasingly repetitive.

Then there’s something very different with Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon. This strip originally began in 1950, well ahead of the Space Race, and it's fascinating that neither the US nor USSR are the first to get to the lunar surface. The rocket here is, apparently purposefully, reminiscent of the Nazi's V-2 rocket, even down to the distinctive red and white check. That surely makes Professor Calculus a comedy version of Von Braun. Again, there's no mention of Nazis, the shadow of occupation or the Cold War that followed - and was in the background as this story was written. Tintin is the first human to walk on the Moon but this extraordinary historic moment happens outside of time.

Herge took pains to get the details right, and it's fun to see a spacecraft built to accommodate the fact that its crew would all be knocked unconscious by G-force. The astronauts speculate about the formation of craters (we now know they're created by impacts), and land and drive huge, heavy vehicles on the lunar surface that would be far too massive and costly to get there. I was also taken by the science they actually conduct:

“EXTRACT FROM THE LOG BOOK BY PROFESSOR CALCULUS 4th June - 2150 hrs. (G.M.T.) Wolff and I spent the day studying cosmic rays, and making astronomical observations. Our findings have been entered progressively in Special Record Books Nos. I and II. The Captain and Tintin have nearly finished assembling the [reconnaissance] tank.” (p. 98)

They set up an observatory and a theodolite, and drive round in an enormous tank. And then they discover a huge cave system. Surely, surely, the moment Tintin lets go his safety line and drops into the abyss to rescue Snowy is an influence on Doctor Who doing the same in the The Satan Pit (2006).

So much of this is jaw-dropping, remarkable and new. Really, my only problem with the Moon story is the villain, who returns from King Ottaker's Sceptre in a simple revenge plot, while a rival bunch of scientists eavesdrop on what Tintin is up to. It feels inconsequential.

Once they're back on Earth, Tintin is recognised as the first person to walk on the Moon in several of the books that follow. The Calculus Affair is set on Earth but feels no less huge given that Professor Calculus has - as well as all his technology for getting to the Moon - invented a super weapon. There's a chilling moment when we see a city destroyed, though it proves to be a model for demonstration purposes. Even so, this analogy for the Bomb is really effective. At one point, we also spot a book, "German Research in World War II", the first time the Tintin series references the conflict.

Tintin in Tibet (serialised 1958-59, book version 1960) seems quite similar to Nigel Kneale's Yeti stories - his TV play The Creature (1955) and the movie version The Abominable Snowman (1957) - and I wondered if Kneale had been an influence. Here, Tintin is on the trail of his friend Chang, last seen by us in The Blue Lotus - 15 books previously, and first published in the 1930s. Clearly, not so much time has passed for the two young friends. Tintin now seems to have a psychic ability, knowing innately that Chang is alive and in need of saving. Psychic powers seem permissible when he's among exotic natives.

The Castafiore Emerald is on a much smaller scale and set largely at Haddock's home, Marlinspike Hall. Haddock is not the most patient or progressive of people but is horrified by the treatment of a group of Travellers nearby and offers them land on which to camp. They are then suspected when Bianca Castafiore is robbed - playing into racial cliches. Yet Tintin maintains that the Travellers are innocent, even when evidence suggests otherwise. It's Herge trying to play against racist assumptions but there's no challenging of or comeuppance for the prejudiced authorities, and the Travellers leave without a word. The story's heart is in the right place but it's odd. The culprit turns out to be a bit of a joke, and there's little sense of the injustice done to the Travellers. In fact, a missing watch rather invites us to suspect them, too.

Flight 714 to Sydney involves the return of a whole load of friends and foes from previous books, and the plot reminded me a lot - and not in a good way - of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. There are more returning characters in Tintin and the Picaros, including characters not seen since all the way back in The Broken Ear. If that's not very original, the story is full of suspense - our heroes walking headlong into a gilded cage, and a great sequence at the end when they get caught up in a crowd as they race to save the Thompsons from execution.

Our last sight of Tintin is in a tiny panel at the top of the final page. We then hear him on the final row, a speech bubble snaking away to a departing aircraft. And that's it: a rather understated end to his adventures and a great shame. For all the repeated jokes and perils, and the myriad returning characters that are hard to keep track of, it's all still fun - and now and again really thrilling.

The collection ends with Herge's script and rough sketches for two-thirds of Tintin and Alph-Art. It's fascinating to see his process, and the difference between the roughest of rough sketches and the couple of examples or more carefully realised outlines. The story itself is quite different from what's gone before - involving a celebrity modern artist who makes sculptures based on the letters of the alphabet. But there's the usual runaround and chases, Tintin surviving various attempts to shoot him and blow him up. It's hard to judge without the last third. Would it have done something different?

I'm also amazed that it's not been completed officially, and that, like Asterix, there aren't new adventures of Tintin. For one thing, the movie suggested an openness to adaptation on the part of the licence-holders. There's surely a story in what Tintin did during the war years, or in what he's up to now.

But then I think part of Tintin's appeal, and the only possible response to the racism contained in the stories, is that he's a thing of the past.