Now Susan is marrying someone else — but, she tells Nancy, she’s received a threatening note from an ex. Susan wants Nancy, who kept notes in shorthand on Susan’s love-life when they lived together, to seek out her exes and find out who is making trouble. It might be the convicted thief Peter or the poet Laurence or the vain actor Mike… Nancy is sure it can’t be Donald.

When Susan is murdered, Nancy’s first thought is to ensure that the police don’t suspect her fiancee. But in tidying up the crime scene to protect Donald, she incriminates herself…

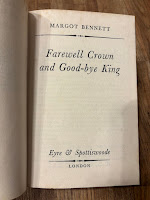

This is a fantastic return to form by Margot Bennett after the disappointment of Farewell Crown and Good-bye King. It’s at least as good as The Widow of Bath and probably better, my favourite of her books that I have read so far. I can see why it won the Crime Writers’ Association ‘Crossed Red Herrings’ award — since renamed the Gold Dagger (and presented to Bennett by JB Priestley) — and why Bennett was, in 1959, elected to the Detection Club. Fast-moving, twisty and suspenseful, this keeps us guessing to the end. Even the very last paragraph takes an unexpected turn.

In his introduction, Martin Edwards quotes Bennett herself on what made this and The Man Who Didn’t Fly “my best books”. The latter,

“had an unusual plot and a set of people I believed in. In the same way, Someone from the Past had five characters I might have met anywhere. The best of all my people was the girl Nancy. She was kind and cruel, and loyal and bitchy. She was a ready liar, with a sharp tongue, but she was brave and real. All through my books, the best I have done is to make the people real.” (pp. 9-10, citing John M Reilly (ed.), Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers)

Nancy is a compelling protagonist. We never know what she might do next. She is observant and reckless, intelligent and yet capable of extraordinary folly. Sometimes she tries to fix things in ways we can see (and want to shout) will only make things worse. But we are with her all the way as she faces multiple dangers.

As so often with Margot Bennett, characters attracted to one another bicker and fight, but here the stakes are raised because any one of these men Nancy is winding up could be the murderer. Whether or not they did for Susan, they can be violent with Nancy, or treat her appallingly in other ways. In fact, she is not the only woman here who puts up with variously crap men.

This British Library Crime Classic edition, first published in 2023, is subtitled “a London mystery” and it boasts a few good descriptions of places such as Soho. More than that, it offers an extraordinary snapshot of the mores of 1958, the year the novel was originally published. As well as a lot of smoking and drinking, there’s a surprising nonchalance about drugs. Tired and wound-up after a row with Donald, Nancy tells us:

“I knew I should take a couple of strong sleeping-pills. They would give me four hours’ sleep, and a heavily-doped morning that would make work impossible, unless I took a stimulant. After that, a couple of tranquilizing tablets would level me up for the day.” (p. 37)

She has all of these to hand as, a few pages later, she offers them and “a confidence drug” to her fiancee, who tells her he’s already taken “knockout pills” (p. 45). These, we learn, are “blue things, sodium amytal” (p. 47). Elsewhere, Nancy seems familiar with benzedrine. The drug-taking is part of the plot (one suspect was apparently doped and unconscious at the time of the murder) but also part of everyday life.

I’m intrigued by elements of the novel that Bennett may have drawn from her own (fascinating) life, such as her years as a writer for the magazine Lilliput (while her husband Richard Bennett was editor).

“From the moment that I got the job on the Diagonal Press and scrawled out my first paid illiteracies I saw myself as a great writer, one who kept notebooks and would soon be guest of honour at literary luncheons.” (p. 27)

Again, the notebooks are part of the plot but I wonder how much this attitude — to her earlier work and to her career — matched Bennett’s own. When the murder case bears down on Nancy, the publisher she works for offers her a chance to get away with a job in Spain (p. 248). Is that a nod to Bennett’s own history, as she served as a nurse (and publicist) in Spain during the civil war?

Then there is what the novel says about Television, which in those days still had a capital T. Bennett had already made her debut as a TV writer: her one-off drama The Sun Divorce (dir. Philip Savile) was shown as part of London Playhouse on the ITV network Associated-Redifussion on Thursday 26 January 1956, just four months after the launch of ITV. Writing of Someone from the Past must have overlapped with the agreement of rights for a TV adaptation one of her earlier novels: The Man Who Didn’t Fly, starring William Shatner and Jonathan Harris, was adapted by Jerome Coopersmith and broadcast by NBC in Canada on 16 July 1958.

Since it was made and broadcast in Canada, Bennett probably had little involvement in this and she may never have seen it. But, excitingly, we can watch that production of The Man Who Didn’t Fly on YouTube. It even enjoys a bit of a following because it stars both William Shatner and Jonathan Harris, later stars of Star Trek and Lost in Space respectively.

Margot Bennett was soon writing for TV herself, with work on ATV soap opera Emergency-Ward 10, perhaps making use of her own nursing experience. IMDB credits her on 15 episodes of the soap, broadcast between Tuesday 23 September 1958 and Friday 22 May 1959. The implication is that she moved into soap opera soon after completing work on this novel.

By the time she finished on Emergency-ward 10, Bennett had made the switch to BBC — and more prestigious drama — with her six-part adaption of her novel The Widow of Bath, which began transmission on 1 June 1959. But Someone from the Past suggests she was already familiar with the mechanics of BBC television more than a year before that.

In the novel, actor Mike Fenby, presumably used to late nights on stage followed by late mornings (as described in Exit Through the Fireplace), complains of the “brutal creatures” of “Terrivision” who have him up at “ten o’clock” in the morning for rehearsals in Shepherds Bush — which is where the BBC was based.

“And you should see, I really wish you could see, the producer. Temperament! He thinks out the sets with a kind of telescope, and when he wants to concentrate, he blows bubbles. … He has a tin. He shakes the bubbles off with a bit of wire. They help him to relax. When they burst, they cover the floor with slime, like invisible banana skins. There’s practically no one in the cast who hasn’t a sprained ankle or a broken neck. You ought to see us, skidding about the place.” (pp. 39-40).

That “telescope” was a director’s viewfinder, enabling the director to see how much of the actors and set would be visible through different diameter lenses, and to plan and block their shots ahead of studio recording. Viewfinders had been in use since at least 1938: the Tech Ops site boasts a clipping from Radio Times that year, a photo of one in use and some other details. But this is not the sort of thing people outside the world of TV were likely to know about,.

Actor Mike can escape from rehearsals for lunch with Nancy at one o’clock, suggesting “a pub called the Blue Unicorn”, which is surely a play on the real-life White Horse at 31 Uxbridge Road, where I’ve also sometimes met up with actors. (For those with an interest in the drinking habits of old TV people, the late Alvin Rakoff says in his memoir of working for the BBC in the 1950s that after recording at Lime Grove he’d take the crew for a pint at the end of the road, in the British Prince at 77 Goldhawk Road.)

Later, Mike can’t believe Nancy didn’t see his TV performance go out.

“‘I thought you might have been interested enough to watch me on the new medium.’

‘It’s a fairly old medium by now, isn’t it?’

‘But Nancy, this was terrific. I’m a brain surgeon, you see, who takes to drink, and just when I’m having a terrible fit of the stagers, my former loved one is wheeled in with her brains dashed out. I’m supposed to shake so much, the forceps clash together like a steel band as I approach the operating table. The trouble was that I really was shaking so much I dropped the whole kit of instruments on her face. It was Sylvia, you know, she’s got a shocking temper, I cracked the porcelain jacket on one of her front teeth, she’s going to sue me. If I hadn’t got between her and the cameras and ad-libbed, the viewers would have heard every word she said. You certainly missed something. It will be in all the papers tomorrow.” (p. 95)

There’s a lot of interest here (to me): Television no longer a novelty, favouring melodramatic productions in which the viewer might enjoy the emotional crisis of characters in close-up, all within the lively, stressy chaos of live broadcast. The depiction is a bit pointed, even satirical — as is Mike buying up all the papers to bask in the contradictory reviews — but the details are all right, and so surely based on direct observation.

Did Margot Bennett have first-hand experience of BBC drama production when she wrote Someone from the Past, more than a year before her first writing credits at the BBC? Her husband had worked in BBC radio since the war and also sometimes wrote for listings magazine Radio Times, such as his interview with Jimmy Wheeler ahead of a TV comedy show in May 1956. Yet it seems unlikely that Margot tours of TV rehearsals through that connection.

More probable, I think, is this came through her own efforts. Was she meeting with BBC people about writing for TV, and getting tours of production, long before her first screen credit there? Or perhaps, like Nancy, Margot Bennett simply met an actor friend for lunch while they were in rehearsals…

Whatever the case, and for all Bennett might have mocked TV drama, something extraordinary happened after the publication of Someone from the Past. Despite the accolades it won, she never published another crime novel. According to her family (and detailed in the introduction to the British Library edition of The Man Who Didn’t Fly), she didn’t earn enough from novels to continue; crime didn’t pay. Instead, she spent the next decade writing prolifically for TV.

More investigation to follow...

Novels by Margot Bennett:

- Time to Change Hats (1945); Away Went the Little Fish (1946); The Golden Pebble (1948); The Widow of Bath (1952); Farewell Crown and Good-bye King (1953); The Long Way Back (1954); The Man Who Didn’t Fly (1955); Someone from the Past (1958); That Summer’s Earthquake (1964); The Furious Masters (1968)

Non-fiction by Margot Bennett: