First a review of The House of Silk, and then some other items of Sherlockian interest...

The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz is a thrilling, richly drawn new Sherlock Holmes adventure, that gets Holmes, Watson and their world pretty much perfectly right. It's a gripping read, and even though I was ahead of Holmes with several of the clues, it kept me guessing till the end. Yet, it left me disappointed. Why?

The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz is a thrilling, richly drawn new Sherlock Holmes adventure, that gets Holmes, Watson and their world pretty much perfectly right. It's a gripping read, and even though I was ahead of Holmes with several of the clues, it kept me guessing till the end. Yet, it left me disappointed. Why?

The edition I read included a bonus feature: "Anthony Horowitz on Writing The House of Silk: Conception, Inspiration and The Ten Rules". It's fascinating to read the rules Horowitz set himself when writing the book - such as "no over-the-top action", "no women", and "no gay references either overt or implied in the relationship between Holmes and Watson". But including those rules is also surely a challenge to the reader: how would you write Holmes?

Horowitz's rules seem largely to do with not repeating the mistakes or attempting to emulate over iterations of Holmes, and to stick closely to the canon of stories written by Conan Doyle. But they didn't explain my misgivings with the book.

Horowitz is keen to slot his book seamlessly into the canon. I found the constant references to other, canonical cases a bit wearing. One rule - "include all the best known characters - but try and do so in a way that will surprise" - struck me as odd. Yes, he's got Mrs Hudson, Lestrade, Mycroft, Wiggins, and even an appearance by someone Holmes hasn't yet heard of - a fact that, to fit with the canonical stories, requires some awkward contriving:

That depth is partly the result of the length of the book.

All of which, again, I cannot fault. And yet, these two aims - to fit The House of Silk perfectly within the canon, and to explore the world of Holmes - also also what left me dissatisfied. In the latter, the world we explore is murky and cruel, with corruption reaching so high into the establishment that even Myrcroft is powerless to act.

One of the mysteries that Holmes exposes is particularly vicious - and of a kind Doyle himself could not have published in his own time. It's not the crime but the way it fits Horowitz's general character of Victorian London that makes it so affecting: Holmes might stop what's happening, but only in this one instance.

On top of this, in fitting this adventure into the canon, Horowitz also seeks to reconcile a continuity error in Doyle about when exactly Watson married. Some Sherlockians have conjectured that Watson was married twice; Mary Morstan - who Watson married at the end of The Sign of Four - must have died at some point and Watson remarried. Horowitz confirms this hypothesis, with Mary mortally ill.

That the whole book is narrated from after Holmes has died only adds to the bleak feeling. For all his rules, Horowitz has missed a key ingredient of the canon: the element of joy. Holmes might walk through the mire of crime, but the stories celebrate his brilliance. The Final Problem, in which Holmes meets his match, is affecting and extraordinary precisely because it's so unlike the norm - and, in The Empty House, even the great detective's death turns out to have a solution.

That's what The House of Silk sadly misses: Sherlock Holmes is not about awful problems but the ingenious answer.

I think the current run of Sherlock on BBC One has got the mad, thrilling flavour of Doyle just right. I adored The Sign of Three last week, but my chum Niall Boyce was bothered by the central wheeze: that a victim would not know they'd been stabbed because of the tightness of their clothing. Niall's an editor of the medical journal, the Lancet, so tends to spot these things.

In fact, just such a killing has a precedent - and from Doyle's own time. Elisabeth, Empress of Austria, was murdered in September 1898:

You may also care to note that I passed Doyle's house in South Norwood a couple of months ago. And, if you've not already discovered it, John Watson's blog - written with some assistance by m'colleague Joseph Lidster - has been especially good this series.

The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz is a thrilling, richly drawn new Sherlock Holmes adventure, that gets Holmes, Watson and their world pretty much perfectly right. It's a gripping read, and even though I was ahead of Holmes with several of the clues, it kept me guessing till the end. Yet, it left me disappointed. Why?

The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz is a thrilling, richly drawn new Sherlock Holmes adventure, that gets Holmes, Watson and their world pretty much perfectly right. It's a gripping read, and even though I was ahead of Holmes with several of the clues, it kept me guessing till the end. Yet, it left me disappointed. Why?The edition I read included a bonus feature: "Anthony Horowitz on Writing The House of Silk: Conception, Inspiration and The Ten Rules". It's fascinating to read the rules Horowitz set himself when writing the book - such as "no over-the-top action", "no women", and "no gay references either overt or implied in the relationship between Holmes and Watson". But including those rules is also surely a challenge to the reader: how would you write Holmes?

Horowitz's rules seem largely to do with not repeating the mistakes or attempting to emulate over iterations of Holmes, and to stick closely to the canon of stories written by Conan Doyle. But they didn't explain my misgivings with the book.

Horowitz is keen to slot his book seamlessly into the canon. I found the constant references to other, canonical cases a bit wearing. One rule - "include all the best known characters - but try and do so in a way that will surprise" - struck me as odd. Yes, he's got Mrs Hudson, Lestrade, Mycroft, Wiggins, and even an appearance by someone Holmes hasn't yet heard of - a fact that, to fit with the canonical stories, requires some awkward contriving:

"You must swear on everything that is scared to you that you will never tell Holmes, or anyone else, of this meeting. You must never write about it. You must never mention it. Should you ever learn my name, you must pretend that you are hearing it for the first time and that it means nothing to you."But are these characters' roles surprising? As Horowitz admits,Anthony Horowitz, The House of Silk (2011), p. 260.

"In each case, I added very little to what was known about them simply because it seemed to be taking liberties."Where he does develop the world of Sherlock Holmes. As Horowitz says, in Doyle's stories,Ibid., p. 404.

"Victorian London is economically sketched in".Horowitz digs a little deeper: there's an insight into the kind of awful existence lived by the Baker Street irregulars when not engaged in cases for Holmes; there's a visit to one of the prisons to which villains are dispatched when Holmes has caught them. In both cases, Watson seems surprised by the oppressive conditions, as if a practising doctor in London would not already know. But I liked the attempt to explore the world Holmes lives in and furnish extra depth.Ibid., p. 397.

That depth is partly the result of the length of the book.

"My publishers, Orion Books, had requested a novel of between 90,000 and 100,000 words (the final length was around 94,000) - big enough to seem like value for money on an airport stand. But actually, this goes quite against the spirit of Doyle's originals which barely run to half that length".Horowitz's solution is to have Watson recount two cases, not one - a trick also used in the later episodes of the TV series starring Jeremy Brett, where they blended Doyle's stories.Ibid.

All of which, again, I cannot fault. And yet, these two aims - to fit The House of Silk perfectly within the canon, and to explore the world of Holmes - also also what left me dissatisfied. In the latter, the world we explore is murky and cruel, with corruption reaching so high into the establishment that even Myrcroft is powerless to act.

One of the mysteries that Holmes exposes is particularly vicious - and of a kind Doyle himself could not have published in his own time. It's not the crime but the way it fits Horowitz's general character of Victorian London that makes it so affecting: Holmes might stop what's happening, but only in this one instance.

On top of this, in fitting this adventure into the canon, Horowitz also seeks to reconcile a continuity error in Doyle about when exactly Watson married. Some Sherlockians have conjectured that Watson was married twice; Mary Morstan - who Watson married at the end of The Sign of Four - must have died at some point and Watson remarried. Horowitz confirms this hypothesis, with Mary mortally ill.

That the whole book is narrated from after Holmes has died only adds to the bleak feeling. For all his rules, Horowitz has missed a key ingredient of the canon: the element of joy. Holmes might walk through the mire of crime, but the stories celebrate his brilliance. The Final Problem, in which Holmes meets his match, is affecting and extraordinary precisely because it's so unlike the norm - and, in The Empty House, even the great detective's death turns out to have a solution.

That's what The House of Silk sadly misses: Sherlock Holmes is not about awful problems but the ingenious answer.

I think the current run of Sherlock on BBC One has got the mad, thrilling flavour of Doyle just right. I adored The Sign of Three last week, but my chum Niall Boyce was bothered by the central wheeze: that a victim would not know they'd been stabbed because of the tightness of their clothing. Niall's an editor of the medical journal, the Lancet, so tends to spot these things.

In fact, just such a killing has a precedent - and from Doyle's own time. Elisabeth, Empress of Austria, was murdered in September 1898:

|

| The assassination of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, via Wikipedia. |

"After Lucheni struck her, the empress collapsed ... Three men carried Elisabeth to the top deck and laid her on a bench. Sztaray opened her gown, cut Elisabeth's corset laces so she could breathe. Elisabeth revived somewhat and Sztaray asked her if she was in pain, and she replied, "No". She then asked, "What has happened?" and lost consciousness again...Niall also provided me with two snippets of Sherlockian interest from the Lancet archives, which he's kindly allowed me to share. First, here's Conan Doyle weighing in on the case of George Edalji - the case that's the subject of the novel Arthur and George by Julian Barnes, which I blogged about in 2007.

The autopsy was performed the next day by Golay, who discovered that the weapon, which had not yet been found, had penetrated 3.33 inches (85 mm) into Elisabeth's thorax, fractured the fourth rib, pierced the lung and pericardium, and penetrated the heart from the top before coming out the base of the left ventricle. Because of the sharpness and thinness of the file the wound was very narrow and, due to pressure from Elisabeth's extremely tight corseting, the hemorrhage of blood into the pericardial sac around the heart was slowed to mere drops. Until this sac filled, the beating of her heart was not impeded, which is why Elisabeth had been able to walk from the site of the assault and up the boat’s boarding ramp. Had the weapon not been removed, she would have lived a while longer, as it would have acted like a plug to stop the bleeding."

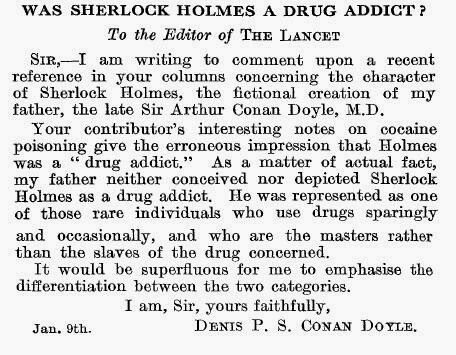

Niall also tweeted this later contribution from Doyle's son, "Was Sherlock Holmes a Drug Addict?", in 1937:

No comments:

Post a Comment