In Australia, sheep farmer Jack Dorman finally pays off decades of debt and - despite a large tax bill to come - realises he is now wealthy. His wife Jane is worried about her elderly Aunt Ethel back in England, who she's not seen in 32 years (when Ethel was the sole member of Jane's family to back her relationship with Jack). Jane intuits that Ethel is short of money, so the Dormans, who've regularly sent Ethel letters and cake mix, now send her £500.

Things are far worse than they could imagine, and Ethel is starving to death in her nice house in Ealing, having sold most of her furniture and anything else of value from her days abroad. Ethel's granddaughter, Jennifer Morton, finds her in this state and cares for the old woman in her last days. But the book is pretty blunt about what has done for this poor woman: having once lived a rather grand life in Petersfield and then as a dutiful wife of empire out in Burma, she's been left destitute and unnoticed by, er, the new National Health Service. The independence of India has also meant the end of her pension. It's as if no one was neglected before the NHS; that before the welfare state there was no need of welfare. Or perhaps there's something more sinister: that if only we still had an empire and people knew their place, this sort of thing wouldn't happen to someone of her class.

The war is also to blame, but the privations suffered in England - which are ever increasing, long after the end of the war - seem to be the fault of the post-war government so far as the author is concerned. Jennifer works for a ministry, and we're told,

"It was manifestly impossible for anyone who derided the Socialistic ideal to progress very far in the public service; if a young man aimed at promotion in her office he felt it necessary to declare a firm, almost a religious, belief in the principles of Socialism." (p. 91)

It's quite a claim, but really it's Shute who is being unfairly partisan. The sense is of an old, glorious England now lost to the awful unfairness of egalitarianism. Dying, Ethel tells Jennifer,

"It's not as if we were extravagant, Geoffrey and I. It's been a change that nobody could fight against, this going down and down. I've had such terrible thoughts for you, Jenny, that it would go on going down and down and when you are as old as I am ... you'll think how very rich you were when you were young." (p. 71)

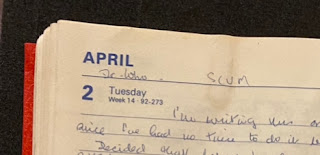

When the old woman dies, Jennifer's father goes through her things and finds a telling document - a recipe for a cake given to Ethel on her wedding day.

"What a world to live in, and how ill they must have been! His eyes ran back to the ingredients. Two pounds of Jersey butter... eight weeks' ration for one person. The egg ration for one person for four months... Currants and sultanas in those quantities; mixed peel, that he had not seen for years. Half a pint of brandy, so plentiful that you could put half a pint into a cake, and think nothing of it. ... He had eaten such cakes when he was a young man before the war of 1914, but now he could hardly remember what a cake like that would taste like." (p. 77)

The irony, of course, is that this woman starved to death, with only the cake mix to sustain her.

Ethel leaves her new money to Jennifer, making the girl promise to use it to visit Jane in Australia, and perhaps look for a better life there - like the one Ethel once knew in England. The doctor who treated Ethel is also leaving the country for a better life but Jennifer has reservations about leaving her elderly parents. Others suggest Australia will "probably be all desert and black people" (p. 95), or make an economic case for the value of migrants as an investment made by a particular country.

"For eighteen years somebody in this country fed you and clothed you and educated you before you made any money, before you started earning. Say you cost an average two quid a week for that eighteen years. You've cost England close on two thousand pounds to produce. ... Suppose you go off to Canada. You're an asset worth two thousand quid that England gives to Canada as a free gift. If a hundred thousand like you were to go each year, it'ld be like England giving Canada a subsidy of two hundred million pounds a year. It's got to be thought about, this emigration." (p. 89)

Despite this, Jennifer sets off to Australia for a temporary visit, certain she will then return home. At 24, she has never eaten grilled steak until boarding the ship - which comes as a great surprise to the Australians (p. 135). She in turn thinks very highly of their modest work in farming and producing food. A lot is made of the virtue of hard graft. The Dorman's have become wealthy after 32 years of toil, and repeatedly say they're glad that wool prices will soon fall so that their children don't end up too indolent. At the end of the book, Jennifer is appalled by a man visiting a doctor in the NHS wants,

"medicine and a certificate exempting him from work because he couldn't wake up in the morning." (p. 314)

Yet on the very same page, Jennifer organises things so that the doctor in question can have more lunches and dinners away from his patients, helping him to bunk off. And then,

"She was staggered to find out how much her mother's illnesses had cost, how much her father had been paying out in life insurance premiums for her security (pp. 314-5)

- presumably under the old, unjust system that the NHS replaced.

In Australia, there is no desert and there are no aboriginal people, though migrants from eastern Europe are treated as a lower order. Jennifer is welcomed by the Dormans, and cannot persuade their young daughter that a trip to England will only be a disappointment. Then there's a serious accident and no doctor available to help two men desperately in need. Carl Zlinter, a Czech immigrant working the land, was a doctor in his own country before serving with the Nazis, but he is not allowed to practice in Australia without retraining for three years. With the men in desperate peril, Jennifer assists Zlinter in carrying out highly risky operations to save the two men's lives, but one of them doesn't survive.

As an inquest looks into this and threatens to deport Zlinter, he gets closer to Jennifer, and is also haunted by the discovery of a gravestone bearing his own name and place of origin. It's for a man who died some decades previously, on the cusp of living memory. Zlinter is soon on the trail of the surviving, elderly people who might have known his namesake and can shed light on his story...

This particularly struck a chord because I'm researching the life of David Whitaker, who in 1971 adapted this novel for Australian TV (broadcast on ABC in 1972). Just as with Zlinter, I've been tracking down surviving paperwork and trying to speak to now-elderly people who might remember my man. There are many parallels between The Far Country and Whitaker's life. In 1950, he was living with his family in Ealing, streets away from the fictional address of Aunt Ethel. The house may also have had relics from India, where Whitaker's mother was born. The age difference between Zlinter and Jennifer is similar to that between Whitaker and his first wife June Barry. As with Jennifer, June Barry returned to Australia leaving Whitaker to work in Australia, with a shadow over their future together...

In fact, for all Jennifer clearly falls for Australia, there is plenty here to count against moving to this far country. There's the boredom of life on the farms, especially for the lone women keeping homes there. There's palpable danger given the lack of qualified doctors and the frequent risks of fire. There's also the philistine culture. Zlinter isn't the only one whose skills are overlooked in Australia. He buys a painting of Jennifer from Stanislaus Shulkin, a plate layer on the railway line who was once professor of artistic studies at the University of Kaunas.

Perhaps there's something here of the author: an engineer who also wrote novels, at once dirty-handed grafter and lofty man of arts. But surely it can't be a virtue to overlook the talents of Zlinter and Shulkin; it's squandering the investment, just as Shute argued before.

For all Australia offers a future to those prepared to work, Zlinter and Jennifer's happiness is secured by an inheritance that comes quite by chance and to which they're not entitled, requiring Zlinter to transact business with some slightly dodgy characters. He and Jennifer agree to keep the details secret - implicitly because they know that this is wrong. It's a necessary cheat because (just as with the Dormans), the rewards take a long time to win if they're to come at all. There are plenty of characters for whom things haven't worked out.

One reading of all this might be that Shute sets up an initial prejudice - bad old England against verdant, rich Australia - which he then proceeds to complicate and pick at, resulting in a richer, more complex portrait. But if so, the case is made in bad faith and the result is a very odd book.