The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book was the third of three books by Terrance published by Target on 16 December 1976. I’ve addressed them in the order I think they were written: the manuscript of the revised version of The Making of Doctor Who had been approved by 22 April that year; Doctor Who and the Pyramids of Mars must have been delivered by the end of May, given my estimated 7.5-month lead time for novelisations; then there was this relatively late commission.

The evidence for that lateness includes the fact that Target did not feature The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book in lists of forthcoming publications such as the one published in fanzine TARDIS, vol 1, no. 8 (July 1976), which cites every other title planned for 12 months:

The Dinosaur Book is also missing from the list of other Doctor Who books available featured in Doctor Who and the Pyramids of Mars; this is not a list solely of novelisations because The Making of Doctor Who is included.

The suggestion is that when this novelisation was in lay out, Target still weren’t sure whether the Dinosaur Book would be ready in time for publication on the same day.

This is also the first, and only, Doctor Who book written by Terrance that does not have his name on the cover: he is credited on the title page inside. Given his renown by this point, as script editor and writer on the series, and author of 13 novelisations as well as other Doctor Who titles, my suspicion is that this is evidence of rush.

Then there’s what George Underwood, illustrator of The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book, told me when I interviewed him last month:

“I looked it up in my job book. It was [done] in August [1976].”

In that single month, George produced all 32 illustrations: 28 double-page spreads and three single-page images in monochrome pencil, plus the cover art in acrylic colour (the pale blue background done with an airbrush).

“Man, the hours I must have put into it!”

The limited time in which he completed this colossal undertaking suggests a late commission for the book as a whole. For comparison, I’ve worked on some books where we talked to the illustrator more than a year before publication.

The tight turnaround surely explains why the book wasn’t illustrated by Chris Achilleos, already busy producing book covers for Target. I put that to George:

“Yeah, Chris did a lot of Doctor Who stuff. I’m sure they’d have gone to him first. Then they needed someone else, so they’d have asked around and my agent at the time must have sold me to them. They decided to use me."

George had some history with dinosaurs, having previously provided the mind-bending artwork for My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows (1968), the debut album of Marc Bolan’s band, Tyrannosaurus Rex.

“That had creatures in it but there I used Gustave Dore’s engravings as inspiration. So this was different.”

He’d also produced artwork for his friend David Bowie, such as the rear sleeve painting for the album David Bowie (1969, now better known as Space Oddity), and colour hand-tinting Brian Ward’s black-and-white photography for the covers of albums Hunky Dory (1971) and The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972). He also produced gatefold artwork for a planned Ziggy-related live album that ultimately wasn’t realised.

In the summer of 1976, George was a jobbing freelance illustrator and took work as it came.

“I was doing a lot of commercial work just to pay the rent, so I was happy when this came in. Book covers and illustrations were much more enjoyable to work on than advertising, where often an agency came up with awful ideas you then had to solve. I can come up with my own ideas! I didn’t have much to do with the negotiations. The money was probably okay.”

Having been taken on by Target,

“I’d have gone into the office [at 123 King Street in Hammersmith] at least once. I worked for [art directors] Brian Boyle and Dom Rodi on other things as well, but I don’t remember which of them was on this.”

No designer is credited in the book itself, but some sources credit Frank Ainscough, who later oversaw the Doctor Who Discovers series of books; George didn’t recognise that name. This suggests that Rodi oversaw the Dinosaur Book but followed the style Boyle established in The Doctor Who Monster Book (where he is credited).

George told me that he “may have met” Target’s children’s books editor Elizabeth Godfray but had no direct dealings with writer Terrance Dicks.

“The BBC sent me some great [photographic] shots of the Doctor in various poses as reference. I had to find ways to manipulate those and fit them into the backgrounds with the monsters, to make it look as if the Doctor was there. That was important, to give the right sense of scale.”

When Terrance worked on The Doctor Who Monster Book, he sourced photographs from the BBC himself and wrote his copy to fit them. He seems not to have been involved in commissioning artwork, such as the cover. Indeed, in several interviews Terrance said he’d sometimes be asked by editors what he wanted on the covers of his books, and never knew what to say.

I asked George if he’d been given much of a brief for the illustrations in the Dinosaur Book; I wondered if he was told something like, for example with the spread pp. 38-39, “We see a Polacanthus, like the one on p. 32 of the Ladybird Dinosaurs.” But George said:

“Not that I remember. And I remember doing quite a lot of research myself, checking out other illustrators’ versions of dinosaurs. I already had some reference books at home, encyclopaedias and didn’t the Reader’s Digest do stuff as well? For that particular job, I might have gone out and bought a book on dinosaurs but I’m sure I had some at home which had been given to my children."

On the Love in the Time of Chasmosaurus site, Marc Vincent identified the two key sources for George’s artwork in The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book: Album of Dinosaurs written by Tom McGowen and illustrated by Rod Ruth (Rand McNally, 1972) and Dinosaurs written by Colin Douglas and illustrated by BH Robinson (Ladybird Books, 1974). There is a full LITC post on The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book.

As that post says, some of the images in the Dinosaur Book are very like the sources they’re drawn from:

|

| Cover of Album of Dinosaurs (1974) art by Rod Ruth |

|

| “Tyrannosaurs rex”, in The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book, art by George Underwood after Rod Ruth |

|

| Stegosaurus and Antrodemus by BH Robinson from Dinosaurs (Ladybird, 1974) |

|

| “Allosaurus v Stegosaurus” in The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book Art by George Underwood after BH Robinson |

George openly acknowledged this in a 2016 interview:

“That was the only way I could do it. It’s not like there were any walking around my back garden at that time. Any artist who does a dinosaur book has to look at what’s been done before. It’s impossible to make anything up.” (George Underwood, interviewed by Graham Kibble-White, “Scary Monsters”, The Essential Doctor Who — Adventures in History (June 2016), p. 91.

Of course, he was under extraordinary pressure to deliver a lot of work in a short amount of time. And he wasn’t alone in this; as we’ve seen in previous posts, Chris Achilleos appropriated material from other artists in his cover art for Target Books, such as Daleks from the comic TV Century 21 and Omega’s hands from an issue of The Fantastic Four. I’ve spoken to a few artists who say this sort of thing was quite common in commercial illustration.

But look at this example:

|

| Tyrannosaurus rex by Rod Ruth Album of Dinosaurs (1972) |

|

| “Fighting Tyrannosaurus” The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book Art by George Underwood in part after Rod Ruth |

See what George also adds: another Tyrannosaurus of matching type, but from the opposite angle, and a curled up Anatosaurus — consistent with his standing Anatosaurus on pp. 26-27. If he uses the same posture, he changes skin texture, tone and other details. Elsewhere, he changes posture to a greater or lesser extent, or provides wholly new compositions.

George also supplied his own characteristic features, such as the “pie-crust” spines seen on these Anatosaurus and other dinosaurs in the book (and noted by Mark Vincent as distinctive). Then there are his unique creatures:

|

| “Compsognathus” The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book Art by George Underwood |

This portrait of Compsognathus seems to be entirely George’s own creation, as he explained to me:

“It’s not very different from a modern lizard. They’d sent me that photograph of the Doctor in kneeling position, and that led what I could do. Sometimes you just had to make it up. Especially the colouring.”

|

| Sarah and the Doctor examine a clue Black Archive: Planet of Evil |

*

George wasn't the only one who had to work quickly: Terrance had lots of other work on at the time. As well as the two books published on the same day as this one, he wrote an episode of the TV series Space: 1999. The treatment for this, then called Brainstorm, is dated 4 March 1976 and the final shooting script — renamed The Lambda Factor — is dated 6 August, with a series of amendments made during September and October as it entered production.

His next novelisation, Doctor Who and the Carnival of Monsters, was published on 20 January 1977 so, based on my estimated lead time of 7.5 months, was delivered around the end of June 1976. He followed this with Doctor Who and the Dalek Invasion of Earth, presumably delivered at the end of August as it was published on 24 March 1977.

What’s more, on 22 July 1976, Terrance sent an extensive pitch for a non Doctor Who project to Carola Edmonds at Tandem Books. In his covering letter, he said that he would be away on holiday until mid-August. In summary:

4 March — Treatment for Space:1999 episode Brainstorm

22 April — MS of The Making of Doctor Who approved by the publisher

≅ end of May — delivers Doctor Who and the Pyramids of Mars

≅ end of June — delivers Doctor Who and the Carnival of Monsters

22 July — synopses and sample chapters for original book project for Tandem; heads off on holiday

6 August — “Final” shooting script for Space: 1999 episode The Lambda Factor (presumably delivered before 22 July but now approved by production team)

≅ end of August — delivers Doctor Who and the Dalek Invasion of Earth (presumably written on holiday)

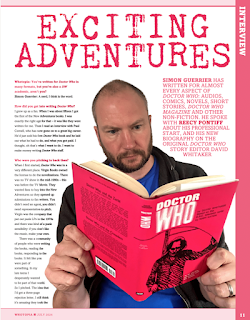

Somewhere into this we must fit The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book, a non-fiction title entailing research as well as writing. I’ve plenty of experience in typing multiple projects at once and the prospect of squeezing a whole extra book into the above schedule doesn’t half make my head swim.

Can we narrow down any further when Terrance wrote this book? Given that it’s missing from the list published in TARDIS, I think it must have been commissioned no earlier than June 1976 and was written June-July, perhaps overlapping with Doctor Who and the Carnival of Monsters.

That novelisation may have been written first, and perhaps even inspired this new book. This is all highly speculative, but my current line of thought is as follows:

A number of things may have inspired The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book. First, The Doctor Who Monster Book, published just before Christmas 1975, sold extremely well, Target boasting 150,000 sales by summer 1977 (Bookseller, 30 July 1977, p. 425). By the summer of 1976, Terrance and his publishers would have known it had been a success. If they could produce a new book in a similar format in time for Christmas 1976, they might replicate that success.

What would this new book entail? Well, The Doctor Who Monster Book focused on the fictional monsters of the TV series. The follow-up would focus on real-life monsters. Dinosaurs are popular with children anyway, so a Doctor Who dinosaur book would surely have wide appeal. A book children might buy for themselves, and a book an adult would buy for a child they knew (or suspected) liked Doctor Who, dinosaurs or both.

Terrance already understood the crossover appeal of dinosaurs. It was the basis on which, as script editor, he commissioned the TV story Invasion of the Dinosaurs (1974). His eldest son Stephen remembers being taken by his dad to see the dinosaurs at London’s Natural History Museum, as well as to see the film One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing (1975) — one of the first projects on which actor Jon Pertwee worked after leaving Doctor Who.

Perhaps the response of his children to these trips inspired Terrance to suggest a Doctor Who dinosaur book. Perhaps someone else came up with the idea, to which he was receptive.

Then there was the format. The Doctor Who Monster Book was a 64-page “magazine format” title, the colour cover artwork reproduced in a pull-out poster, and the rest of the book comprising black and white text and illustrations. That’s the format of the Dinosaur Book as published, too.

But The Doctor Who Monster Book comprised photographs from TV stories alongside repurposed artwork by Chris Achilleos from the covers of novelisations (and one piece by Peter Brooke). This included cover artwork from four books not yet published when the Monster Book came out.

It occurs to me that the initial idea may have been to do something similar with the Dinosaur Book. That’s because, around the time that this new book was devised, Achilleos was commissioned for his third cover to feature prehistoric creatures: the plesiosaur on Doctor Who and the Carnival of Monsters follows a Tyrannosaurus rex on Doctor Who and the Cave-Monsters and the kklaking pterodactylus on Doctor Who and the Dinosaur Invasion.

What’s more, the novelisation Doctor Who and the Sea-Devils is about (fictional) creatures from the same time as the dinosaurs, and Doctor Who and the Loch Ness Monster has a dinosaur-like antagonist (a fact referenced in the Dinosaur Book as published). Did Achilleos or someone at Target realise they had five pieces of artwork that would suit a dinosaur-themed Doctor Who book?

Dinosaurs had appeal in their own right. But also, as with the Monster Book, each piece of reused artwork would, effectively, advertise an existing novelisation, increasing sales all round. Ker-ching.

I think that makes sense as the starting point for this project. But, given the late commission and the problems experienced the previous year on The Doctor Who Monster Book, it would have soon become evident that there wasn’t time to clear the rights for a wealth of photographs from the TV series. Instead, they would need to increase the proportion of or entirely use new artwork.

Achilleos was the obvious choice to provide this additional work, alongside his existing dinosaur-related covers. That would be consistent, Target clearly had a good, long-standing relationship with him, and his work seems to have been in favour with the production team on Doctor Who and other parts of the BBC (where I’m aware of complaints about artwork, it involved the work of other artists).

At the same time, I can see why Achilleos, offered the chance to produce almost a whole book’s worth of new illustrations in a single month, politely declined. Having met Chris a few times, I can well imagine his pained expression.

In that case, the decision was made to find another artist to turn round this project quickly. And that fits with what George Underwood told me, above.

*

Whatever the case, Terrance had to research and write this new book pretty quickly. We don’t know the sources he worked from, but I wonder if taking his son to the Natural History Museum was part of the legwork on this book.

The 52-page Ladybird Dinosaurs book keeps us waiting: after spreads on early life in the sea, amphibians and early reptiles, life in the sea and the air, and then modern humans discovering footprints and “bones” (not fossils) from which we can piece together the forms of ancient animals, the first dinosaurs appear on pp. 26-27, exactly halfway through.

Terrance gets down to business much more quickly. The introduction (pp. 6-7) begins with a breezy,

“Hello! I’m the Doctor. If you’ve been following my adventures, you’ll know I’ve met some pretty fearsome monsters in my travels around the Universe.”

This direct address to the reader — implying that the Doctor knows we are watching him on TV — immediately makes us part of the adventure to follow. The Doctor mentions some of these monsters he’s encountered — Daleks, Cybermen, Ice Warriors and the Loch Ness Monster — then says,

“You once had more than your share of monsters right here on Earth.”

A pedant (hello) might point out that the Doctor had, at the time this was written, encountered Daleks, Cybermen, Ice Warriors and the Loch Ness Monster on Earth. But he’s talking native species, conjuring a lost world quickly and vividly.

“Huge, terrifying creatures with savage fangs and claws. Monsters of all shapes and sizes, on land, in the seas, and even in the air.”

This “Age of the Monsters” ended before the arrival of human beings — “Perhaps it’s just as well!” — but, he says, left traces:

“fossils, bones, even footprints, and your scientists have done a pretty good job of reconstructing what they looked like.”

That “pretty good job” nicely gets across the idea that all knowledge is provisional, and that the way we imagine the dinosaurs has developed over time — and may yet still change. A nice bit of hedge-betting, too. And then, after just this single page of set-up and what I think is the Doctor’s signature in Tom Baker’s handwriting, we go meet the dinosaurs.

“The Age of the Dinosaurs” boasts the heading of pp. 8-9 in big capital letters. The Doctor stands, hands in pockets, just in front of the TARDIS, beaming at the wondrous sight of two great Apatosauruses in a lake.

“Here we are in the Age of the Dinosaurs,” says the Doctor as tour guide, landing us right in their midst. There’s then some further hedge-betting:

“We’ve travelled back one hundred and eighty million years in Time — give or take a million of two!” (p. 8).

The Doctor explains that we’ll need to hop back and forward in time a bit on this tour to “see a good selection.” The language he uses is interesting; while some dinosaurs are ferocious, these first ones on our tour are “very peaceful, placid”, that last word as per Part Two of Invasion of the Dinosaurs:

DOCTOR WHO:

Apatosaurus, commonly known as the Brontosaurus. Large, placid and stupid. That's exactly what we need.

The newly regenerated Fourth Doctor repeated the phrase “large, placid and stupid” in the first episode of Robot, written by Terrance, so I don’t think the use of the word here is a coincidence.

But is the joke at the end of this first spread also a coincidence? The Doctor tells us that many dinosaurs’ names are “fine old tongue twisters” (but, unlike the Ladybird Dinosaurs and most modern dinosaur books, there’s no guide to pronunciation). Then he adds:

“Still, I suppose such impressive creatures deserve impressive names. It wouldn’t seem right to call a Dinosaur Fred, or Bert…” (p. 9).

As with all licensed material, the text of this book must have been approved by the production team on TV Doctor Who, including script editor Robert Holmes. A couple of years later, he made use of the same joke in the TV series, delivered by the same Doctor:

DOCTOR WHO: What's your name?

ROMANA: Romanadvoratrelundar.

DOCTOR WHO: By the time I’ve called that out, you could be dead. I'll call you ‘Romana’.

ROMANA: I don’t like ‘Romana’.

DOCTOR WHO: It's either ‘Romana’ or ‘Fred’.

ROMANA: All right, call me ‘Fred’.

DOCTOR WHO: Good. Come on, Romana.

Robert Holmes, The Ribos Operation Part One, tx 2 September 1978

The tour continues: Coelophysis is a “little chap” who,

“Nips along on those two back legs with tail stretched out, like a kind of giant bird. His bones are hollow too, just as a bird’s are” (p. 11).

This is on the cusp of something most children now take as read: that birds evolved from the dinosaurs. Later, we’re told that while Pterodactylus “looks and acts like a bird, it’s a reptile right through” and “really isn’t a bird”, but Archaeopteryx is “a reptile that’s actually managed to grow some feathers” but will “take quite a few million years to evolve into the birds you know today” (p. 21).

In fact, the choice of dinosaurs depicted here is very of the time in which it was written. There are obviously the big names — Triceratops, Tyrannosaurus rex, Stegosaurus — and he doesn’t mention Brontosaurus, covering Apatosaurus instead as the then more accurate term. But there’s no Velociraptor of Spinosaurus, which I think are now de rigeur in dinosaur books. There are few specimens found outside the US and UK. I wonder how much the choices of specimen matched the displays at the Natural History Museum at the time.

Having introduced us to Apatosaurus, Terrance gets some narrative going: p. 13 ends with the Doctor noting that one Apatosaurus has seen something of concern. We turn the page and there’s an Allosaurus charging into view. Turn the page again, and the Apatosaurus is feasting on the neck of the poor Allosaurus.

Next page, and we jump in time and space, to see an Allosaurus more evenly matched against a Stegosaurus. Terrance seems keen on even matches — on fair fights — and later we see Tyrannosaurus rex versus Tyrannosaurus rex, and Triceratops versus Triceratops.

Once we get beyond “Allosaurus v Stegosaurus”, the tour jumps about quite a bit, with diversions for creatures in the air and sea. The latter includes Plesiosaurus, though notably without any mention of the Doctor meeting one of these animals in Carnival of Monsters. Indeed, beyond the introduction there is no mention of events from TV adventures; the fiction and fact are kept entirely separate.

The Doctor notes that Polacanthus has “special claim to your [ie the reader’s] interest” (p. 39) as it it is from what is now England and Northern Europe. It’s an odd bit of flag-waving, not least because the Doctor / Terrance doesn’t make the same point in the entry on Iguanodon (p. 22); he tells us that this was one of the first dinosaurs that humans knew about, but doesn’t mention that remains of it, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus — the three animals for which the word “dinosaur” was originally coined — were all found in the UK.

As with his novelisations, Terrance uses everyday analogies to convey ideas simply. Apatosaurus is “as big as a train, but it’s a very slow train” (p. 12) and also as big as a herd of elephants (p. 13); Ankylosaurus is “the armoured tank of the Dinosaur world” (p. 25); Anatosaurus is the dinosaur equivalent of modern-day platypus (p. 26); Compsognathus is “hardly as big as a chicken” (p. 49). When the Doctor examines a Protoceratops egg, he asks us:

“How about one of these, lightly boiled for your breakfast?” (p. 29).

There are some odd things, too. We’re told Tyrannosaurus rex “stands a good six metres high” — metric — and “weighs nearly eight tons” — imperial (p. 42). I suspect a modern edit would get Terrance to look again at the sentence,

“One good bonk from an Ankylosaurus could send the hungry carnivore limping away” (p. 25).

But on the whole, the book gets across a lot of information — and wonder — in a concise and engaging way. It really does feel as if we’re in the company of the Doctor, and I love the idea that, just once, we get to be his companion. And then the book does something brilliant, a proper Doctor Who twist…

I said that the Ladybird Dinosaurs book doesn’t show any dinosaurs until we’re halfway through. We get just seven spreads of dinosaurs, with pp. 42-43 devoted to Archaeopteryx, and the next spread “The first mammals”, including a Megatherium shown — as per the display at the Natural History Museum and the sculpture in Crystal Palace Park — on its hind legs, reaching up to eat the branches from a tree.

The Ladybird book then covers “More mammals”, “The first horses”, “The woolly rhinoceros” and “The wooly mammoth” — the latter shown hunted by humans. Finally, there’s a sabre-toothed-tiger.

This, I think, influenced the end section of The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book, but Terrance makes it all more dramatic. First, there’s the spread “The End of the Dinosaurs”, where the Doctor — shown sat brooding beside a huge dinosaur skeleton, not entirely unlike the one in One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing — shares some theories about how dinosaurs died out. Cold temperatures, lack of appropriate food, not protecting their eggs, and some mysterious disease are all mooted. Of course, this book was published long before the Alvarez hypothesis, the scientific idea that inspired the Doctor Who story Earthshock (1982), though a line in that story echoes what the Doctor says here:

“Perhaps one day I’ll come back in the TARDIS and find out what really did happen…” (p. 53).

The next spread is devoted to Megatherium, and here the Doctor is part of the classic way of depicting this animal: he is holding the tree branch from which the great creature is feeding, while up on its hind legs. The Doctor tells us some facts, such as that this is an ancestor of the sloth, then warns us about the next specimen on the tour:

“Now it’s time to move on again. Around half a million years ago an entirely new creature was on the scene. It was the fiercest and most dangerous killer ever to walk the Earth…” (p. 55).

That’s quite a claim after Tyrannosaurus rex. We turn the page, to “An Animal Called Man”. The same gag was done later by David Attenborough in the series Life on Earth (1979): after 12 episodes observing different animals in the wild to tell the story of evolution, the 13th episode applies the same observational techniques and objective style of narration to humans in everyday, modern life.

The next spread in the Dinosaur Book is a naked man, bare bum to the fore, spearing a Smilodon, “a giant sabre-toothed cat” which now “won’t have much to smile about” (p. 58). The next spread shows humans hunting a Mastodon clearly based on the image in the Ladybird book. The use of Megatherium, Mastodon and Smilodon suggests Terrance himself drew from the Ladybird book for this last section of the (text of the) book, but while that book is setting out chronological context, Terrance makes it a story with a twist.

Terrance used a version of this twist again in his short story, Doctor Who and the Hell Planet, published in the Daily Mirror on 31 December 1976, a fortnight after publication of this book. You can read the whole story at the Cuttings Archive. My suspicion is that this story was written to tie into and promote The Doctor Who Dinosaur Book, given the connection in setting and twist, though there’s no plug for the book in the paper.

Nerd that I am, I find myself wondering if the events of the short story occur during the tour the Doctor gives us in the Dinosaur Book, which would mean we — the reader — are there, too, a bona fide companion.

It’s a beguiling idea. In fact, Terrance ends the Dinosaur Book with the prospect that we might enjoy further adventures with the Doctor.

“Perhaps we could take another trip some time? Just keep an eye out for an old blue police box. I gather your police aren’t using them any more. So if you do see one, it’ll probably be my TARDIS… Goodbye!” (p. 64).

How brilliant, how tantalising. What an extraordinary and odd book, and how much I’ve enjoyed digging into its past.

*

Thanks to George Underwood, to Nicholas Pegg (author of The Complete David Bowie) and to palaeontologist Dr David Hone for answering my questions in preparing this post. All errors by me. Brush your teeth.