This is, after Doctor Who — The Three Doctors, the second Doctor Who novelisation not to employ an “and the” title. At least, the “and” is missing from the front cover of my first edition of this book. On the spine and title pages, and in most references to this novelisation, it is Doctor Who and the Revenge of the Cybermen. It is only from the front cover that the word has been deleted.

This was clearly done to make a long title fit the established cover template. On Terrance’s next novelisation, the long title Doctor Who and the Genesis of the Daleks was made to fit by reducing the vertical height of the letters, still set in Futura Condensed ExtraBold, from 6mm to 5mm, or from 40pt to 35pt (based on the typeface I have for reference).

The team at Wyndhams — who published Doctor Who The Revenge of the Cybermen simultaneously in hardback and paperback on 20 May 1976 — initially intended to shorten the title still further, presumably to make it better fit the template. “[Doctor Who and] The Cybermen’s Revenge” is the title given on a list of “Advance information on Doctor Who novelisations in preparation” sourced from Wyndhams, handwritten by Graham Wellfare and reproduced on p. 92 of Keith Miller’s The Official Doctor Who Fan Club vol 2.

As I said in my post on that book, this list sadly isn’t dated but the first title given is [Doctor Who and] The Green Death by Malcolm Hulke, to be published “Aug 75” at 35p [in paperback]. That implies that this list was written before publication of that book on 21 August 1975 but after publication of the previous Target novelisation, Doctor Who and the Terror of the Autons, on 15 May.

The title was also “Cybermen Revenge” in Terrance’s handwritten notes for Chapter 10 of the in-progress novelisation. The three pages of notes are undated but were written between dated entries on other projects on 6 September and 6 October 1975.

Therefore, I think Terrance wrote and delivered the manuscript for Doctor Who and the Cybermen’s Revenge in September 1975, under that title. My guess is that the production team then wanted to retain the title used on screen, as would be the case for all Doctor Who books from pretty much this point on (Doctor Who and the Space War, published 23 September 1976, was the last novelisation to rename a story). The awkward step of deleting “and” from the front cover of this book but not from the spine or title pages suggests that the change was made late in the process.

That original title for the book would have made this a closer match to Doctor Who and the Cybermen by Gerry Davis (published 19 February 1975), adapted from the TV story The Moonbase (1967), which Davis co-wrote with Kit Pedler. I think that may be part of a wider, conscious effort to link these two novelisations.

For the cover of Doctor Who and the Cybermen, Chris Achilleos produced a stippled, black-and-white portrait of the Second Doctor, including his collar and bowtie, framed by an image of the Moon (the setting of the story) with a flaming and dappled black border suggesting outer space.

A Cyberman in the lower left of the frame stares impassively back at us. It’s the wrong Cyberman for the TV story, based on a photograph of the redesigned Cybermen from 1968 story The Invasion. But perhaps that was on purpose, to align more closely with the versions seen on TV in Revenge of the Cybermen, broadcast just weeks after this book was first published.

When producing cover artwork for Doctor Who The Revenge of the Cybermen, Achilleos seems to have had this earlier artwork in mind. Again, there’s a stippled-black-and-white portrait, this time of the Fourth Doctor, including the top-most part of his scarf. He is framed by an image of fiery space bordered by nebulous black. It’s not space station Nerva or the rocky asteroid of Voga that are the settings in the story; I think that makes it closer in style to the cover of Doctor Who and the Cybermen. Again, there’s a Cyberman in the lower left of frame. This time he faces another alien creature, a Vogan.

The big difference between the two covers, I think, is that the Second Doctor looks serious, suggesting a serious story, while the Fourth Doctor is beaming. The portrait is based on a photograph of Tom Baker on location for The Sontaran Experiment (1975), but in that photograph Baker’s expression is a bit more determined and grim, teeth gritted rather than smiling. Achilleos has also made the Doctor's hair fluffier and more bouffant. It’s a gleeful Doctor, not one fighting for his life.

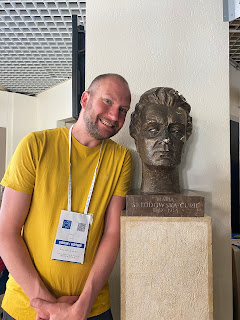

|

| Tom Baker filming The Sontaran Experiment c/o The Black Archive |

There's something similar going on in the depiction of the monsters. On TV, the Cybermen tower over their victims — Terrance refers to them more than once in this novelisation as “silver giants”. But the Cyberman and Vogan here are the same height; indeed, the relative positions of eyes, mouth, chin and shoulders suggest that the Vogan is actually taller.

There’s little sense that these two figures are deadly enemies; they seem to be smiling at each other. It doesn’t help that there’s something about this particular Vogan that’s a bit Private Godfrey from Dad’s Army…

As a whole, the composition lacks the dynamism and excitement of other work by Achilleos, such as Omega’s hands burning into the foreheads of the Three Doctors, or the kklaking pterodactyl of Doctor Who and the Dinosaur Invasion. By placing the Cyberman on the left, as per Doctor Who and the Cybermen, and the Vogan on the right, the latter’s arm and body obscure much of the two-handed sci-fi raygun he is holding. For ages, I thought he was proffering some kind of ornate gift or bit of technical apparatus: a friendly gesture, not a threat to kill. Again, there’s no sense of him fighting for his life.

All in all, it’s a rather jolly-looking cover, at odds with the grim tone of the novel inside.

Before we get into the contents of the book, there’s one more thing to address about the cover which has a bearing on the words inside. The name given under the title is Terrance Dicks, not Gerry Davis.

Davis seems to have written the novelisation Doctor Who and the Cybermen around the same time as he wrote the scripts for what became Revenge of the Cybermen on TV. The two stories share a number of elements. For example, both feature what was then a new class of Cyberman — a “Cyberleader” (sometimes, in the novel, also a “Cyber-leader”). Both stories involve a “virus” that the Doctor is able to show is not a virus at all, but a toxin spread by the Cybermen as a prelude to taking control of a remote, human-crewed outpost in space.

In both stories, the human crew are sceptical of the Doctor’s claims, believing that the Cybermen died out long ago. In Doctor Who and the Cybermen, the silver giants exploit human weakness for sugar and are themselves vulnerable to nail-varnish remover; in Revenge of the Cybermen, they exploit human greed and are vulnerable to gold. The implication, surely, is that in revisiting the older TV story for his novelisation, Davis found some of the structure and plot elements for the new TV adventure.

At that stage, it would also have been logical to assume that Davis would novelise his new TV story in due course. For one thing, of the various Doctor Who stories that Davis worked on over the years, this is the only one on which he received sole credit as writer.

Soon after publication of Doctor Who and the Cybermen and broadcast of Revenge of the Cybermen, Davis tackled the very first Cyberman adventure, Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet, published on 19 February 1976. In previous posts, I’ve estimated a lead-time on these books of 7.5 months; if that applies here, then Davis delivered Doctor Who and the Tenth Planet at the end of July 1975. Just as he finished that book and needed a new assignment, we see that, as per the list of books in preparation cited above, The Cybermen’s Revenge was added to the schedule.

He retained copyright on the scripts of the TV story, so his permission must have been sought and given for this novelisation. But he didn’t write the book. Instead, he went on to novelise other TV stories he had worked on as co-writer and/or story editor, with his next one, Doctor Who and the Tomb of the Cybermen, published on 18 May 1978.

The reason, of course, is that the version of Revenge of the Cybermen that made it to the screen is very different from what Davis wrote — as we can hear in the audio version of the original scripts. The production team felt there were numerous problems with this version and the scripts were extensively rewritten by Robert Holmes in his capacity as script editor, on staff at the BBC. Davis was not happy with the revised version; the upshot was that he retained sole credit and copyright on a story he largely hadn’t written and really didn’t like. Understandably, he didn’t want to novelise this version of “his” story.

That is significant because it means that Terrance Dicks was commissioned on the specific understanding that he would novelise Revenge of the Cybermen as broadcast. This in turn presented him with a challenge I don’t think he’d faced before.

Up until now, he’d novelised Big Event Doctor Who stories: the Third Doctor’s debut, his first encounter with the Daleks and the Master, and his death; the Fourth Doctor’s debut, the Second Doctor’s first encounter with the Great Intelligence, the Three Doctors all meeting up. Even Doctor Who’s encounter with the Loch Ness Monster is a big, iconic moment. These are all good, strong stories, too.

With Revenge of the Cybermen, Terrance was presented for the first time with a TV story that, for all I enjoy it, is fundamentally flawed. When he had been script editor, it was his job to fix problems in storylines and scripts. Here, the brief was to not fix the story but match what went out on screen. At times, I don’t think he could help himself, whether in trying to correct faults or in offering wry comment on illogical proceedings.

The three pages from his notebook relating to this novelisation give some sense of his approach. They cover events in Chapter 10, which is the end of Part Three and start of Part Four of the TV story, with a line break for the cliffhanger.

“Kellman killed

Harry sees K dead

Doc knocked out —

Harry sees Doc — goes to unstrap b[omb]

Commander — stop! Explain [that undoing the strap will set off the bomb]

Doc survives — Harry idiot

Doc says Commander keep on — rest of u will get grd + attack”

There’s no reference here or in the other pages of notes to what we see on screen, such as what people are wearing or what things looks like. That suggests Terrance worked from the words in the camera script — stage directions and dialogue — rather than from a screening of the episodes, which would have provided visual details. The notes are a summary of plot, Terrance establishing for himself the overall thrust of the action before translating each scene into prose.

(ETA: Nicholas Pegg told me on Bluesky me that “A further indication that Terrance was working from the scripts rather than from the TV broadcast is his retention of ‘cobalt bombs’. On screen they became ‘Cyber-bombs’, which [director] Michael Briant told me was part of a general decision ‘to make everything Cyber’.” Thanks to Nick, who knows a surprising amount about Cybermen given that he is Dalek.)

But there is more than that going on here, too. This page of notes includes the word “gyroscope”, which isn’t used in the scripts or the story as broadcast. I think the word was prompted by something else in the script at this point: the machine that the Cybermen use to track the progress of the Doctor as he carries their bomb is a “radarscope”. The word is used in dialogue at other points of the story but it’s also in the stage directions of the script just after the Doctor insults Harry. And I think that word prompted Terrance to use “gyroscope” in a completely different moment in the novelisation, as an apposite word for the very opening sentence:

“In the silent blackness of deep space, the gleaming metal shape of Space Beacon Nerva hung like a giant gyroscope” (p. 7).

The model used in the TV story (and in The Ark in Space) looks a little like the kind of gyroscope that children have as toys, but that single word also conveys a spinning, moving, mesmerising instrument. We do more than visualise the shape; we can feel its intricate, automated workings. It is tangible and a wonder — all from a single word.

There are plenty of other well-chosen words: p. 49, for example, boasts “imperious”, “melodious” and “ostentation”. The explanation of the “transmat beam” vital to one part of the plot is told from Harry’s perspective, so it is at once conversational, easy-going and fun:

“His travels with the Doctor had familiarised him with this latest triumph of man’s technology, an apparatus that could break down a living human body into a stream of molecules, sent it to a predetermined destination by a locked transmitter beam, and reassemble it unharmed at the other end. With transmat you could send a person as easily as a telephone message” (p. 38).

That page of notes above has another well-chosen word, when the Doctor calls “Harry [an] idiot”. He uses a more offensive term on screen and then falls back unconscious. In the book, he follows the rude comment with something kinder:

“Nevertheless I’m very glad to see you again” (p. 102).

The Doctor is nicer than on TV, Harry is not so undermined; both are more heroic.

In opening the novel, Terrance describes Sarah as a “slim, dark pretty girl” (p. 7), by which he means white but brunette. Her “exceptionally good peripheral vision” (p. 17) explains how, on TV, she alone dodges a Cybermat that has killed more than 40 other people. But when she screams, we’re told it’s in “true feminine style”. That’s the view of the omniscient narrator because Harry, from whose perspective this is sometimes told, knows better. For example, he knows that Sarah “always refused to accept the role of the helpless heroine” (p. 90).

Harry is the same “broad-shouldered, square-jawed young man” (p. 7) as in Doctor Who and the Giant Robot and Doctor Who and the Loch Ness Monster. He has the same vocabulary as in the former, referring here to all the “ruddy gold” (p. 47) on Voga. But there’s a steely side to Harry that we don’t really see on screen, such as when the villainous Kellman is killed in a rockfall that’s partly Harry’s fault.

“Harry felt no sympathy. As far as he was concerned, Kellman had been luckier than he deserved.” (p. 100).

The Doctor, meanwhile, is a “very tall, thin man whose motley collection of vaguely bohemian garments included an incredibly long scarf, and a battered soft hat jammed on top of a mop of wildly-curling brown hair” (p. 7). It’s the first time in print, I think, that this incarnation is described as “bohemian” — though note in this case that it is only “vaguely”.

(For all his love of specific, well-chosen words, Terrance can also often be vague. On p. 64, two things in quick succession are described as “some kind of”…)

That opening page of the novel also introduces the lead character as “that mysterious traveller in Time and Space known as ‘the Doctor’”, repeating the phrase from The Doctor Who Monster Book and Doctor Who and the Loch Ness Monster; less description now as slogan.

There’s also a reference to the Doctor’s “habitual cheery optimism”, which seems more Terrance than the TV story, and at odds with the lofty, “Olympian detachment” Tom Baker was told to convey by producer Philip Hinchcliffe. It is, I think, a sense of the Fourth Doctor had Terrance stayed on as script editor beyond Robot.

Speaking of which, we’re told it’s been a “few weeks” (p. 8) since that adventure. On TV, the first episode of Revenge of the Cybermen aired 13 weeks after the last part of Robot. Working solely from on-screen evidence, has such a lengthy period really elapsed for our heroes? I would have said it was days.

Page 8 has two footnotes, each referring the reader to other novelisations by Terrance: Doctor Who and the Giant Robot and Doctor Who and the Genesis of the Daleks. The latter was the next of his Doctor Who books to be written and published, so had clearly been scheduled at the time he wrote this — begging the question: why didn’t he write that one first? It’s as if these books were purposefully published in reverse of the order of broadcast so that readers had to puzzle out the correct sequence, encouraging them to be active collectors.

On TV, Revenge of the Cybermen begins with the Doctor, Harry and Sarah finding themselves back on space station Nerva and referring to the previous time they were there, in The Ark in Space. A novelisation of that story had not yet been scheduled, so Terrance omitted these lines and instead makes reference, in his narration, to the adventure they have just concluded, and their efforts to “prevent the growing menace of the Daleks” (p. 8). The continuity references are to Terrance’s other Doctor Who books.

There are a couple of further examples of that: the Doctor uses an eye glass (p. 40 and p. 59) as per Doctor Who and the Giant Robot, and there is a reference to Harry Houdini (p. 121) as per Doctor Who and the Planet of the Spiders. In Terrance’s most recently completed novelisation, Doctor Who and the Loch Ness Monster, there’s reference to the Brigadier’s “recall device”. Here, it’s the “Space-Time telegraph” (p. 127) as per dialogue in the script — where it is “space-time telegraph”, lower case. The book ends with a scene inside the TARDIS, the Doctor tracing the signal to Loch Ness, nicely cueing up the next / previous novelisation.

The continuity of the Cybermen is interesting. Terrance knew the history of the silver giants, having detailed it in The Doctor Who Monster Book, but there’s no reference to their previous encounters with the Doctor here. Humans, on Nerva, have only vague recollections of the Cybermen (p. 30), just one of several species to attack Earth in its early space-faring years. Again, that is as per The Moonbase.

These Cybermen wear “clothes” (p. 64). We’re told several times that they’re emotionless and without feelings, which is a fundamental characteristic, sort of Cybermen 101. But on TV, the Doctor taunts them:

“You've no home planet, no influence, nothing. You’re just a pathetic bunch of tin soldiers skulking about the galaxy in an ancient spaceship.” (Part Three)

What is that all about?

In the novelisation, we’re told that when the Doctor says this, he “seemed to be determined to be as tactless as possible” (p. 76) and “seemed to be set on provoking their captors”, after which “it seemed almost possible to detect the overtones of hate in the Cyberman’s voice”, as the Doctor continues in the same way, “infuriatingly”. It is not clear if this narration is from the perspective of one of the human observers, but the repeated use of “seemed” is Terrance suggesting an explanation for what happens in the script, without imposing his view.

Responding to the Doctor, the Cyberleader’s voice rises in volume and intensity. The Doctor continues being annoying and,

“For some reason this childish insult finally broke through the Cyberleader’s control” (p. 77).

It lashes out, exactly as the Doctor has planned; he uses rage against the machine.

I don’t think a Cyberman losing its temper is inconsistent with it being emotionless. It’s sometimes said of the Cybermen that they’ve had their emotions deleted or surgically removed — but what bit of the brain would that be, exactly?

The academic paper that first coined the term “cyborg” and which I think is key to the original conception of the Cybermen, “Cyborgs and Space” by Manfred E Clynes and Nathan S Kline (1960), suggests the use of “an emergency osmotic pump containing one of the high-potency phenothiazines together with reserpine” to automatically respond to abnormal “thought processes, emotions, or behaviour” in the human test-subjects surgically altered for work out in space. The idea was to chemically suppress the emotions.

If the same thing is happening with the Cybermen, they can be emotionless and yet capable of emotion. The Doctor just has to find the right means to trigger them. Note to anti-Cybermen forces: being infuriating and childish works, as here; but don’t waste your time wanging on about sunsets and nice meals, as in Earthshock (1982).

Less fathomable is the sequence in which the Cybermen strap bombs to the Doctor and two humans, then insist that they carry these into the depths of the asteroid Voga. The Cybermen say that, once in the right position, the bombs will begin a 14-minute countdown, allowing the Doctor and the others time to escape with their lives. The Doctor thinks but does not say,

“Pull the other one, it’s got bells on” (p. 82).

So why does he then do as instructed? Well, with the Cybermen using a radioscope to monitor the humans’ progress, and able to detonate the bombs remotely if they veer off course, the Doctor feels he has no other option to escape than to do as bidden, then use the 14-minute countdown to defuse the bombs (p. 83). But we are then told that the Cyberman have anticipated exactly this response; in fact, there is no 14-minute countdown and the bombs will simply explode when they reach the right position. The Cybermen have lied to the Doctor so that he unwittingly does what they want (p. 85).

It’s a clever bit of psychology. But then, almost immediately, one of the other humans asks the Doctor if he really thinks there will be a 14-minute countdown. “I doubt it,” says the Doctor (p. 85). He doesn’t believe the Cybermen’s story, and the humans are at least suspicious. The Cybermen’s clever bit of psychology hasn’t fooled anyone.

So, er, why then is the Doctor willing to carry the bombs into the depths of the asteroid? Well, he says Micawberishly, that he is hoping for something to turn up (p. 86). It’s all a bit woolly and confused, the Doctor relying on luck. We can see that Terrance tried to make sense of it as he wrote this section, but not entirely successfully — because, I think, he couldn’t veer too far from what had been broadcast.

As on screen, Voga is both an asteroid (p. 18) and planet (p. 30), the idea being that the new asteroid is the last-surviving fragment of the planet. On screen, it is also described as a satellite — ie moon — of Jupiter, to which the Doctor responds:

“What, do you mean there are now thirteen?” (Part One)

Terrance cut this line, perhaps because he knew that a 13th moon of Jupiter had already been found by the time of publication: Leda, discovered on 14 September 1974. A 14th moon, Themisto, was spotted in 1975 but not confirmed until years later. But Terrance also refers to Voga as a meteorite (p. 43), suggesting his knowledge of space science was on a par with his knowledge of cars.

The plot hinges on Voga being an asteroid/planet/satellite/meteorite comprised largely of gold, which is immediately lethal to Cybermen. We see the evidence of this on screen: throw a bit of gold in their general direction and they choke and die. Yet Cybermen can also teleport into the caverns of Voga, stomping around and battling Vogans there with no perceived adverse effects. I suppose Terrance could have fixed this by suggesting that the gold must be forced into their breathing systems, and in sufficient quantities, to be deadly. Perhaps that would only have served to highlight this basic flaw in the story.

But I think the fundamental problems of Revenge of the Cybermen are the structure and the tone. Let’s start with the structure.

The blurb lays out the stakes:

“A mysterious plague strikes Space Beacon Nerva, killing its victims within minutes. When DOCTOR WHO lands, only four humans remain alive. One of these seems to be in league with the nearby planet of gold, Voga… Or is he in fact working for the dreaded CYBERMEN, who are now determined to finally destroy their old enemies, the VOGANS? The Doctor, Sarah and Harry find themselves caught in the midst of a terrifyingly struggle to death—between the ruthless, power-hungry Cybermen and the desperate determined Vogans.”

A central part of the story, then, is who Kellman really works for. Yet I think, ironically for a story about Cybermen, that it is difficult for us to care.

The trouble is that Kellman is, when we meet him, a sardonic, mean-spirited character. There is no great mystery about him being involved in the “plague” that has killed more than 40 people. This horrible fact is not mitigated by the discovery that he is really working for the Vogans, not least because it seems he does so because they will pay him in gold.

Villains in other stories, such as Broton or Davros, present articulate reasons for the evil they do, challenging the Doctor. Kellman offers no such challenge. In fact, he speaks in cliches — at one point using what Terrance calls, “one of science fiction’s immortal cliches” (p. 65). There is no redemption: he proves to be a bit cowardly and is then killed in a rockfall. The usually kind-hearted Harry has no sympathy at all. Kellman deserves only scorn.

That is unusual for Terrance, who so often in a conflict endeavours to see the other point of view. And I think that is the fundamental problem here: there is no depth to or interesting aspect of Kellman. I find myself wondering what Terrance would have done had he been allowed to fix this.

My sense, from the notes he gave as script editor to writers on other stories (available in the production paperwork included on the Blu-ray boxsets), is that he would have wanted to simplify unfolding events and concentrate on revelations of character. So, with that in mind…

At the start of the story, Kellman should be the last person we’d suspect of controlling the Cybermats or working with the Cyberman. A kindly, warm-humoured character, to whom our heroes — and we — take a shine. Only later, when he’s exposed, should we see his colder, more ruthless side, as when James Bond shifts from charmer to hitman. That, in turn, would give the actor a bit more to work with.

Then, over time, we come to learn his vital but morally difficult mission: sacrificing the crew of Nerva to gain the trust of the Cybermen so that he can destroy them and in doing so save countless more lives. Just as Harry learns that he’s got Kellman completely wrong, that the man is a hero, they are both caught in a rockfall. Kellman dies. And Harry realises that he will have to complete the mission, no matter the cost…

Something along those lines. But I think if you can fix Kellman, you fix much of what’s wrong in this story.

Then there’s the tone. The story begins with the Doctor and his friends returning to Nerva to find, instead of Vira and their other friends from The Ark in Space, something out of a horror film for grown-ups. Terrance acknowledges the effect:

“For the rest of her life Sarah Jane Smith was to be haunted by the memory of that nightmarish stumble down the long curved corridor filled with corpses” (p. 14).

It is not a moment of peril in a science-fiction adventure, where our heroes are at risk. It is them stalking their way through the carnage of something brutally realistic that has already taken place and so they are powerless to stop. It is horrific because it is hopeless.

Later, Harry witnesses the brutal death of someone at first hand, and we’re told “it remained for ever photographed on his memory” (p. 107). Then, the Cybermen are defeated and Nerva and Voga are saved, but on screen there's barely time to draw breath or acknowledge what our heroes have been through before they head off to their next adventure.

Terrance adds a brief moment of reflection, addressing the oddness of this, with Sarah,

“surprised to find herself as calm as she was. She supposed so much had happened recently that they’d both lost the capacity to be surprised” (p. 127).

It’s a damning diagnosis. The implication is that Sarah and Harry are both suffering from PTSD… Either that, or from bad writing.

*

These great long posts take time to put together and incur expenses. I’ll keep doing them while I can afford to, so do please support the cause if you are able.

Next time: the last of the Mounties books, War Drums of the Blackfoot, which borrows some of the plot of one of the Doctor Who stories on which Terrance was script editor. And then it’s Genesis of the Daleks…