I've a handful of things in the new issue. As well as featuring (for the third time) as one of the beauties on page 3 (see below), there's also a news item about my forthcoming book David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television and the launch for it to be held at the Portico Library on 9 November.

On pages 38 and 39, there's "Effective Management", my interview with VFX editor Matt Nathan - the latest of a regular series in which I pester members of the crew. On page 48, there's the first of a new regular feature by me, "Stasis Cube", devoted to a frozen instant in time (in old money, a "photograph") which is bigger on the inside. It's inspired by the series of blog posts I did 10 years ago, starting with an arresting image from the first episode of Doctor Who.

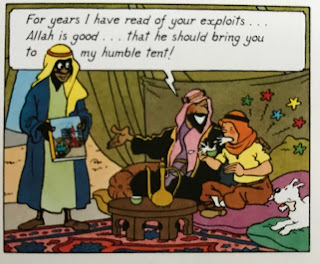

Finally, on page 82, there's the latest "Sufficient Data" infographic, illustrated by Roger Langridge and this time devoted to the number of original instalments of comic strip per incarnation of the Doctor published in DWM over the past 44 years. My post on how I worked out the last "Sufficient Data" seemed to go down well, so here's some more faff about this one.

Deputy editor Peter Ware suggested something related to DWM comic strips to tie in with coverage of The Star Beast. After a bit of thinking, I shared a picture of the "tree maps" we'd used as chapter title pages in our infographics book Whographica, with boxes of different sizes corresponding to the relative number of pages each chapter had.

My idea was to lay a framework of boxes-of-relative-size over a single, full-page illustration of all the Doctors, so that each Doctor appeared in their respective box. I had in mind something like the cover to the first Secret Wars - see my attempt to explain this, right - with lots of characters in one image, and perspective making some bigger than others.This seemed a big ask of the poor artist, so I also suggested that some of the less well represented Doctors might be in silhouette, or in some cases we could use pre-existing artwork from respective eras, blown up in a Pop Art / Roy Lichtenstein way - a David Gibbons Fourth Doctor, a John Ridgway Seventh Doctor, etc. The decision was made to produce one big bit of artwork crowded with 15 Doctors.

With that basic idea approved, I then had to decide exactly what I was measuring.

Editor Marcus Hearn asked for the focus to be on strips from DWM. That was a relief given the volume of comic strips produced by other people. But even this "simple" data set included complications. For example, the first instalment of Ninth Doctor strip Monstrous Beauty wasn't published in a regular issue of DWM but an accompanying supplement. I thought we should include it because it came as part of the package that came with issue #556, so was part of the whole. Marcus went further and asked me to include associated publications. I dug through boxes of old issues working out what this would comprise, and made a list of original comic strips featured in DWM Special Editions, Yearbooks, Storybooks and the 2006 Annual.

DWM has sometimes reprinted comic strips and it didn't seem fair to include the same strip more than once. I initially suggested that they had to be "new to DWM", which meant including in our count some strips first published in Incredible Hulk Presents (Hunger from the Ends of Time! in DWM #157 and #158) and TV Comic (Flower Power in #307). But that surely meant we also had to include all the strips reprinted in Doctor Who Classic Comics, which would have sizeably skewed the figures. We decided to exclude all reprints.

I initially thought I'd count pages of comic strip per Doctor. This proved something of a headache. The very first issue of DWM, then called Doctor Who Weekly, is a good case in point:

- The first episode of main comic strip The Iron Legion comprises five pages

- The Doctor doesn't appear on the first page, so should we count this as four or five pages?

- Do we count the single-panel comic-strip appearances of the Doctor to introduce back-up strips War of the Worlds and The Return of the Doctor? In deciding this, does it matter that these are "new" pieces of artwork rather than reprinted from the main strip?

- Do we include the inside front and back cover, with its full-colour illustrations in comic-strip format, complete with panel boxes, to which readers were invited to add their transfers, creating their own strips? The Doctor features in artwork on both pages.

- Do we include the comic-strip illustration accompanying the letter from the Doctor?

Depending on the answers to the above questions, the Fourth Doctor appears in four, five, six, seven, eight, nine or ten pages of comic strip in this single issue. (Plus there's a photograph of him with a comic-strip style speech bubble.)

If we count pages in which the Doctor appears, things are also complicated by some plot lines where what looks like the Doctor turns out not to be - for example, with the "Nick Briggs" incarnation in Wormwood (DWM #262-#265). There are also strips where events depicted are a dream, such as in The Land of Happy Endings (DWM #337).

Comics material in back issues of DWM also included Lee Sullivan's half-page comic strips advertising Big Finish releases, produced in the same style as his work for the regular DWM strip. If we included those, then why not the comic-style illustrations of text stories or reviews? Given the DWW/DWM regular comic strip can be funny and satirical, was there also a case for including the Quinn and Howett / Nix View / Jamie Lenman / Lew Stringer joke strips? Should I also include pages of comic strip published by DWM/Panini as extra material in collected editions - such as artwork showing the newly regenerated Ninth Doctor featured in the book version of The Flood?

The thing is, there's a useful precedent here. There's a canon of Doctor Who TV episodes, though they can considerably vary in length, and we know which mini-episodes and sketches don't count, however much they might feature the right actors in character tied into the lore. The Five Doctors is an episode and Time Crash isn't. On the same basis as producing infographics on episode numbers, I focused on numbers of instalments of DWM strip.

Even then, I puzzled over how to include Evening's Empire. The first instalment of this was published in DWM #180, then the rest of it failed to appear until published in compendium form some years later. The compendium version used the same artwork from the first instalment but amended some captions and dialogue - so did that make them "original" rather than reprints, meaning they should be counted twice?

Do the collected editions of Evening's Empire and of The Age of Chaos count as one instalment each, or do I count them by the number of episodes/chapters they comprise? Dividing them up was surely counting the format for publication as originally intended rather than how these stories were actually published.

Since we were including Yearbooks and Storybooks published by DWM/Panini, should I also have included the comic strip from Doctor Who Adventures - but only during the period it was published by Panini?

We haggled over this to come up with a discrete set of data from which we could produce a set of different-sized boxes without requiring too many footnotes, which are always a problem to squeeze in to a single-page infographic. We handed this all to Roger Langridge, and he's made it look amazing.