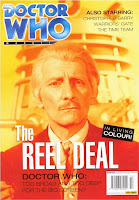

I've been enjoying the new Blu-ray release of the 1985 series of

Doctor Who, adventures that made such an impression on me as kid. And that's prompted me to look out the introduction I wrote for

The Court Jester, the now out-of-print book version of the blog in which

Sue and Neil Perryman watched all the Sixth Doctor's episodes...

Foreword by Simon Guerrier

Thursday, 15 March 1984

My first thought is “good.” Janet Ellis on Blue Peter has just introduced Colin Baker as the new Doctor Who. My family don't buy newspapers and no one's said anything at school, so I'm pretty sure this is the first time I learn that Peter Davison is leaving. I've still not forgiven him for replacing Tom Baker.

Friday, 16 March 1984

The poisonous bat poo the Doctor touched three weeks ago finally kills him. My elder brother and sister join me and my younger brother to watch part four of The Caves of Androzani. I think it's the first time they – now serious, grown-up teenagers – have watched since The Five Doctors. They tell us, as always, that Doctor Who used to be much scarier than this sorry nonsense. I'm certain they're right and can't wait for this story to finish so we can get on to the new Doctor as he's sure to make everything better. I mean, a boy at school insists Colin is Tom Baker's brother.

Thursday. 22 March 1984

The Sixth Doctor era proper begins with part one of The Twin Dilemma. It's a very intelligent story – it must be, as I'm not always sure what's happening or what the Doctor is talking about. It's not exactly a scary story, but the Doctor attacking poor Peri and then later hiding behind her for safety means we're not sure what to make of him. “Look how clever they're being,” I'd tell my siblings if they asked my opinion. But they don't.

Saturday, 5 January 1985

A boring shopping trip to Southampton turns out to be a brilliant trick by my parents, and me and my younger brother are really off to see the stars of Doctor Who in the pantomime Cinderella. Colin Baker runs on to the stage pushing a shopping trolley with a Doctor Who number plate on it, to the most deafening cheer from the audience. People really love his Doctor! My parents' ingenious plan is to see the matinee performance so that we can be home in time for the first episode of the new series of Doctor Who on TV. But we get caught in traffic because of a football match, so I miss Part One of Attack of the Cybermen. There is much weeping.

Saturday, 12 January 1985

I sit entirely baffled by what's happening in Part Two of Attack of the Cybermen, certain it would all make sense if only I'd seen part one. (I don't get to see part one until 1993, and am still not entirely sure what's happening.)

Saturday, 26 January 1985

Part Two of Vengeance on Varos gives me nightmares. I'm really creeped out by the monstrous Sil and the story is full of horrid details, but what really gets me is when the Doctor rescues Peri from being turned into a bird. She looks human but the Doctor has to keep repeating her name to re-imprint her identity. The thought I can't shake is that she might be permanently changed, a monster on the inside...

Saturday, 16 February 1985

ITV shows The A-Team at the same time as Doctor Who. After some discussion with my brother and a friend who doesn't have a telly so is often round to watch ours, we agree to video part one of The Two Doctors and watch The A-Team live. I distinctly remember the logic involved: Doctor Who is the one we'll want to watch more than once. It's not as slick, the fights aren't as good, and it's not so loved by our schoolmates but there's more to each episode. Good thinking, eight year-old me.

Saturday, 9 March 1985

I completely love Part One of Timelash. At school the next week, I insist to a friend that of course bumbling Herbert will be the new companion.

Saturday, 23 March 1985

The scariest moment ever seen in Doctor Who – at least, I think so now. Natasha finds her father, who's being turned into a Dalek and begs her to shoot him. The writing, performance, effects and music are all perfectly horrible. These days, I show a clip of this in talks I give on Doctor Who – just to see the audience squirm. After one talk, the parents of a keen young fan make a point of apologising to me for having told their daughter that Doctor Who wasn't very good in the 1980s.

Saturday, 30 March 1985

We're still watching The A-Team live and videoing Doctor Who, each week recording over the previous episode on the one tape we're allowed to use. Part Two of Revelation of the Daleks is the final episode of this year's series so doesn't get taped over the following week. My younger brother's interest in Doctor Who is waning but my three year-old brother Tom watches that tape again and again for weeks. A moment in that episode haunts me each time I see it, even now. As the Doctor runs down a corridor on his way to battle the Daleks, he thinks he hears Peri being exterminated. There's a moment of horror, of pain, on his face, and then he rallies himself and runs on. No words, just how Colin Baker plays it, so perfectly the Doctor.

Sometime in April 1985

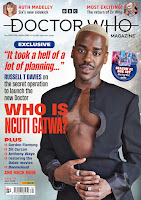

It's all my pocket money, but I spend the vast sum of £1 on the 100th issue of The Doctor Who Magazine. It's a massive disappointment, lacking the weird wonder and excitement the TV series kindles in me. Instead, the magazine is full of lengthy, dense articles about the minutiae of the programme's past. I cannot fathom why anyone would find this of interest. I don't buy DWM again for five years.

Summer 1985, Winter 1985, Spring 1986

Then there's a gap. It came as a complete surprise to me, many years later, to learn that Doctor Who had been on hiatus for 18 months, that there'd been criticism of the violence in the programme, that it was even discussed on the news. At the time, I don't spare the absence a thought – of course Doctor Who will be on again at some point. I don't know there's been a new Doctor Who story, Slipback, on the radio until its released on cassette years later. But I've begun producing my own Doctor Who stories in which my brothers are horribly killed by various monsters.

Tuesday, 24 June 1986

I'm pretty sure I get the novelisation of Timelash for my 10th birthday. The TV version is my favourite of the Sixth Doctor's stories to date, and I read the book over and over. One big appeal is the references to the Third Doctor who, thanks to the Target books I've been picking up second hand and from the library, is my all-time favourite Doctor. But the story also really grabs me, and I spend the summer leaping over the garden sprinkler to be banished back in time.

Saturday, 6 September 1986

Doctor Who returns in a story called The Trial of a Time Lord. I'm especially pleased because we had a school trip to the “ancient” farm at Butser Hill used as a location. But otherwise the first four episodes seem to leave little impression. My memories of the Doctor Who I watched in the 1980s are usually vivid, but when I watch Part One of Trial again on video years later, I'm amazed to discover I can't recall any of what happens next. Perhaps Doctor Who wasn't affecting me as deeply as it once did – no longer the terrifying experience I couldn't bear to miss. Or perhaps these first episodes of the story were completely blotted out of my memory by the ones that followed.

Saturday, 4 October 1986

I am properly terrified by the return of Sil from last year's Vengeance on Varos. This section of the Doctor's trial is the last time Doctor Who ever really scares me. Part of the reason I've stuck with the series all these years on is the morbid hope it will scare me like that again.

Saturday, 1 November 1986

Bonnie Langford makes her début as Mel. My wife says this is when she made the decision to stop watching Doctor Who, which means she still doesn't know the outcome of the Doctor's trial. (Don't tell her.)

Saturday, 6 December 1986

The final episode of The Trial of a Time Lord – and of the year's Doctor Who.

Saturday, 13 December 1986

I sit through hours of programmes on BBC One before the dismal truth sets in that one 14-episode story is all we're getting.

Thursday, 18 December 1986

Colin Baker, in his Doctor Who costume but not quite in character, appears as a team captain on the Tomorrow's World Christmas special. I take this as irrefutable evidence that he's busy filming the new series which must surely start on TV early in the new year. I can't wait!

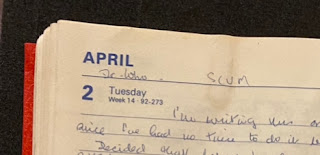

Monday, 2 March 1987

Janet Ellis on Blue Peter has news about the next series of Doctor Who – and chats to her mate Sylvester McCoy who is going to be the new Doctor. I am flabbergasted. Sylvester McCoy is from children's programmes!

Monday, 7 September 1987

The unceremonious end of the Sixth Doctor, who dies by falling over in the TARDIS before the opening titles of Time and the Rani Part One. I sharply recall my embarrassment at how silly the rest of the episode is, sure Doctor Who has lost its way. I've also just started secondary school, and realise that Doctor Who is no longer a programme to be fiercely discussed in the playground over the next week. I mention this to a friend who's gone to a different secondary school and he's astonished. “Are you still watching Doctor Who?”

But I am. It becomes a guilty pleasure. I know – because people keep telling me – that Doctor Who is not as good as it used to be. It was once something everybody watched but now I know hardly anyone who'll admit to having seen the latest episodes.

Today, I know there were problems behind the scenes of the programme: disagreements between those making it, a lack of interest high up at the BBC, a dozen other things. I avidly read – and contribute to – articles in DWM poring over exactly what was to blame. But I also know it was as much to do with the age me and my friends were at the time, and the other pressures and interests affecting us. They simply outgrew this children's programme while I couldn't let it go.

The upshot is that the Sixth Doctor's era marks a fundamental change in my relationship to Doctor Who. Whatever anyone else thinks of this period of the show – and Neil and Sue are about to share their own strong opinions on it – it holds a special place in my heart.

Because at the start of Colin Baker's time as the Doctor, the programme was something I shared with pretty much everyone I knew. By the end, it was mine.

Simon Guerrier

24 April 2017