Spent the weekend typing things as-yet unannounced (two of which I’ve now delivered), then yesterday afternoon saw some sunshine and the

Shah ‘Abbas exhibition at the British Museum (until 14 June).

It’s the latest in the BM’s shows on ‘great rulers’ – following on from

China’s first Emperor and

Hadrian, with Moctezuma to come in the autumn. This seems a less block-busting show than those last two; it was certainly pretty empty yesterday, which meant I could actually get a look at all the exhibits and didn’t have to queue to read any captions. Out of the sunshine and crowds, the dark reading room gave the exhibition a reverent air. A visitor just ahead of me respectfully bowed before each beautifully bound Qu’ran on display; I tried not to make any sound as I followed in my vulgar shorts and flip-flops.

Perhaps the quiet is because the shah or Iran are not such a draw, or it’s because the show lacks any must-see exhibits. There were a lot of faded old rugs and examples of calligraphy, plus examples of Iranian trade: coins and silks from Europe, illustrations from India, crockery from China. Though these were interesting in themselves, there was nothing with particular wow factor. (The Dr also noted that comparatively few of the exhibits came from the museum’s own collections.)

That said, where (as

I blogged in December), the BM’s Babylon exhibition,

“struggle[d] to convey the scale of the Biblical city, squeezed as it is into the upstairs of the old Reading Room,”

there’s a much better sense here of the world these artefacts come from. At the centre of the exhibition were projected huge photos the mosque of Shaykh Lutfullah in his capital, Isfahan, and the shrine of Imam Riza in Mashhad. As so often, I was stunned by the Arabic script worked so beautifully into the plaster – a sign that the workmen were literate.

Shah ‘Abbas promoted Mashhad as a rival place of pilgrimage to Mecca (he expanded Iran’s borders during his reign, but not quite that far). The exhibition was good at explaining the political context of the shah’s reign, too. He established Shi’a Islam as the country’s state religion – which it remains to this day. Yet his reign, says the exhibition guide, was also,

“notable as a period of religious tolerance in Iran – a privilege extended to Armenian Christians, Jews and others.”

It nicely dovetailed the context with English history, as an early caption explained:

“Shah ‘Abbas, like his contemporary Elizabeth I, inherited an unstable country that had recently redefined its religion and was surrounded by powerful enemies.”

Known in English as “the Sophy”, Shah ‘Abbas is mentioned in Twelfth Night and the Merchant of Venice. Reigning from 1587 to 1629, he overlapped with the first two Stewart kings. Yet the Iranian monarchy had very different ideas about the succession – the English monarchs might have bumped off various rivals to the throne, but they didn’t murder their own off-spring.

There’s a small amount on science towards the end of the exhibition. As the caption says,

“The books that Shah ‘Abbas gave the shrine of Iman Riza included an early text from the 1200s on medicinal plants by the ancient Greek scientist Dioscorides. Translated from Syriac into Arabic, his text was one of the foundation stones of medieval Islamic medicine.”

Beside this was a page from book four of Dioscorides’

De Materia Medica, with a picture of something I thought might be a radish, whose seeds it recommends,

“as a purgative, for bruises and itchy skin, and, when, chewed for toothache and painful gums.”

Oddly the illustration doesn’t give the name of the plant – only the picture, which I can see leading to wrong prescriptions. The caption guesses stavesacre (Delphinium staphisagria), though

Wikipedia warns that “all parts of this plant are highly toxic and should not be ingested in any quantity.”

Perhaps the most interesting item in the whole exhibition, though, is one small, innocuous image of the shah with a caption that doesn’t quite spell-out what it seems to be showing. We know it’s the shah from his tell-tale huge moustache (he apparently set a fashion). The image, painted by Muhammad Qasim in 1627 and on loan from the Louvre, has the shah sitting rather close to a long-sideburned page boy. The caption translates the Arabic text: it’s a romantic poem.

This, we’re told, is from a picture album for the shah’s own private enjoyment. It includes the impression of a royal seal, suggesting it’s not propaganda. The Hadrian exhibition had a whole section on pretty boy Antinous – though left him out its family guide. Whatever the purpose or origin of the image here, and though the exhibition frames the picture with a discussion of the succession, it's odd the reference to the Shah's sexuality is only implicit.

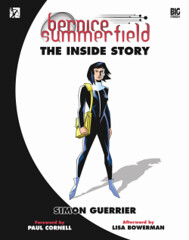

Big Finish have announced that my book, Bernice Summerfield - The Inside Story, will be out in August. Pre-order it NOW and get your copy signed by me and Lisa Bowerman.

Big Finish have announced that my book, Bernice Summerfield - The Inside Story, will be out in August. Pre-order it NOW and get your copy signed by me and Lisa Bowerman.