Out today, The Story of the Solar System - A Visual Journey, is a sumptuous big book of space infographics written by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock off of The Sky at Night with some help by me and design/illustration by Emma Price. Exactly what you and everyone you know wants for Christmas, if you even dare wait that long.

Out today, The Story of the Solar System - A Visual Journey, is a sumptuous big book of space infographics written by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock off of The Sky at Night with some help by me and design/illustration by Emma Price. Exactly what you and everyone you know wants for Christmas, if you even dare wait that long.Thursday, September 26, 2024

The Story of the Solar System, by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock

Out today, The Story of the Solar System - A Visual Journey, is a sumptuous big book of space infographics written by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock off of The Sky at Night with some help by me and design/illustration by Emma Price. Exactly what you and everyone you know wants for Christmas, if you even dare wait that long.

Out today, The Story of the Solar System - A Visual Journey, is a sumptuous big book of space infographics written by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock off of The Sky at Night with some help by me and design/illustration by Emma Price. Exactly what you and everyone you know wants for Christmas, if you even dare wait that long.Friday, October 20, 2023

Carrying the Fire, by Michael Collins

A BRILLIANT BOOK

- THE BEST BOOK

WRITTEN BY AN ASTRONAUT

BY SEVERAL MILLION MILES!£2

For another, I've long admired Mike Collins's insightful, wry and funny perspective on that extraordinary mission, having first seen him interviewed in the great Shadow of the Moon, about which I blogged at the time.

Carrying the Fire really is an extraordinary book, written by a then 43 year-old Collins just four years after the Apollo 11 landing took place. He covers flight school, life as a test pilot, then work as an astronaut leading up to Gemini 10 and Apollo 11, and details those flights in depth. We finish with a chapter ruminating on what it all means and, given the extraordinary achievement that nothing can hope to eclipse, what he might now do with his life.

The book is packed with compelling bits of information, such as the first alcoholic drink the Apollo 11 crew had on returning to Earth. There's even a recipe for the martini in question:

"A short glass of ice, a guzzle-guzzle of gin, a splash of vermouth. God, it's nice to be back!" (p. 445)

For me, the first big surprise was a personal one. My late grandfather (d. 2007) was born William and known to his mother and siblings as Bill but to everyone else as "Roscoe", a monicker that has been passed on as a middle name to various of his descendants. According to legend, Grandpa got this nickname on the day he arrived as a gunner in India in the mid-1930s, on the same day that headlines in the local paper declared that, "Roscoe Turner flies in!"

My family had always assumed that this Roscoe Turner was some military bigwig of the time. It was a delight to learn the truth from an astronaut, when Collins explains why he doesn't like to give public speeches.

"In truth, the only graduation speaker to make any lasting impression on me was Roscoe Turner, who in 1953 had come to the graduation of our primary pilot school class at Columbus, Mississippi. The most colourful racing pilot from the Golden Age of Aviation between the world wars, Roscoe had had us sitting goggle-eyed as he matter-of-factly described that wild world of aviation which we all knew was gone forever. ... Roscoe had flown with a waxed mustache and a pet lion named Gilmore, we flew with a rule book, a slide rule, and a computer." (p. 16)

The next surprise related to my research into the life of David Whitaker, whose final Doctor Who story The Ambassadors of Death (1970) involves the missing crew of Mars Probe 7. We're told in the story that this is just the latest in a series of missions to Mars - General Carrington, we're told, flew on Mars Probe 6. - just as the Apollo flights were numbered sequentially. But I think the particular digit was chosen by David Whitaker because of an earlier space programme, as described by Collins.

"The Mercury spacecraft had all been given names, followed by the number 7 to indicate they belonged to the Original Seven [astronauts taken on by NASA]: Freedom (Shepard), Liberty Bell (Grissom), Friendship (Glenn), Aurora (Carpenter), Sigma (Schirra), and Faith (Cooper)." (p. 138n)

(The seventh of the Seven, Deke Slayton, was grounded because of having an erratic heart rhythm.)

That idea of The Ambassadors of Death mashing up elements of Mercury and Apollo has led me to think of some other ways the story mixes up different elements of real spaceflight... which I'll return to somewhere else. On another occasion, Collins uses a phrase that makes me wonder if David Whitaker also drew on technical, NASA-related sources in naming a particular switch in his 1964 story The Edge of Destruction:

"Other situations could develop [in going to the moon] where one had a choice of a fast return at great fuel cost or a slow economical trip home depending on whether one was running short of life-support systems or of propellants." (p. 303 - but my italics)

Collins certainly has a characteristic turn of phrase, such as when he tells us that, "we are busier than two one-legged men in a kicking contest" (p. 219). This makes for engaging, fun commentary yet - ever the test pilot - he's matter of fact about the practicalities of getting bodies to the Moon and back. For example, there's this, at the end of a lengthy description of the interior of the command module Columbia that he took to the moon:

"The right-hand side of the lower equipment bay is where we urinate (we defecate wherever we and our little plastic bags end up), and the left-hand side is where we store our food and prepare it, with either hot or cold water from a little spout." (p. 362)

This kind of stuff is revealing but I knew a lot of it already from my other reading and watching documentaries. What's more of a surprise, coming at this backwards having read later accounts, is the terminology Collins uses. Flights to the moon are "manned" rather than "crewed", and are undertaken with the noblest of intentions for the benefit of all "mankind" - notable now because the language of space travel tends to be much more inclusive. Then there's how he describes one effect of weightlessness:

"I finally realise why Neil and Buzz have been looking strange to me. It's their eyes! With no gravity pulling down on the loose fatty tissue beneath their eye, they look squinty and decidedly Oriental. It makes Buzz look like a swollen-eyed allergic Oriental, and Neil like a very wily, sly one." (p. 387)

It's a shock to read this - and see it reproduced without comment in this 2009 reprint - not least because Collins is acutely aware of the issue of the Apollo astronauts solely comprising middle-aged white men. Elsewhere, he remarks on his own and the programme's unwitting prejudice in the recruitment of further astronauts. In detailing the rigorous selection criteria, he adds:

"I harked back to my own traumatic days as an applicant, or supplicant, and vowed to do as conscientious a job as possible to screen these men, to cull any phonies, to pick the very best. There were no blacks* and no women in the group." (p. 178)

The asterisk leads to a footnote with something I didn't know:

"The closest this country has come to having a black astronaut was the selection of Major Robert H Lawrence, Jr., on June 30, 1967, as a member of the Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory astronaut group. A PhD chemist in addition to being a qualified test pilot, Lawrence was killed on December 8, 1967, in the crash of an F.104 at Edwards AFB. In mid-1969, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program was cancelled." (p. 178n)

But Collins goes on, in the main text, that the lack of women on the programme was a relief.

"I think our selection board breathed a sigh of relief that there were no women, because women made problems, no doubt about it. It was bad enough to have to unzip your pressure suit, stick a plastic bag on your bottom, and defecate - with ugly old John Young sitting six inches away. How about it was a woman? Besides, penisless, she couldn't even use a CUVMS [chemical urine volume measuring system condom receiver], so that system would have to be completely redesigned. No, it was better to stick to men. The absence of blacks was a different matter. NASA should have had them, our group would have welcomed them, and I don't know why none showed up." (p. 178)

Collins is not alone in this view of women in space: as I wrote in my review, Moondust by Andrew Smith goes into much more detail about the problems of plumbing in weightless environments, and the author concludes:

“Even I find it hard to imagine men and women of his generation sharing these experiences.” (Moondust, p. 247)

But that acknowledges the cultural context of these particular men. The lack of women in the space programme is more than an unfortunate technical necessity; it's part of a broader attitude. Collins enthuses about pin-up pictures of young women in his digs during training and on the Gemini capsule, and tells us bemusedly about a hastily curtailed effort to have the young women in question come in for a photo op. It's all a bit puerile, even naive, of this husband and father.

On another occasion, a double entendre shared with Buzz Aldrin leads to a flight of fancy:

"Still... the possibilities of weightlessness are there for the ingenious to exploit. No need to carry bras into space, that's for sure. Imagine a spacecraft of the future, with a crew of a thousand ladies, off for Alpha Centauri, with two thousand breasts bobbing beautifully and quivering delightfully in response to their every weightless movement..." (Collins, pp. 392-3)

I've seen some of this sort of thing in science-fiction of the period. It's all a bit sniggering schoolboy, and lacks the kind of practical approach to problem-solving that makes up most of the rest of the book. How different the space programme might have been if these dorky men had been told about sports bras.

Later, back on earth, Collins shares his misgivings about taking a job as Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs where he was tasked with increasing youth involvement in foreign affairs. He glosses over the conflict here, of talking to "hairies" - as he calls them - on university campuses in the midst of the conflict in Vietnam. One gets the sense that this was a more technically complicated endeavour than his flight to the moon, and less of a success. It's extraordinary to think of this man so linked to such an advanced, technological project and representative of the future put so quickly in a situation where he seems so out of step with the times.

Collins is more insightful as observer of his colleagues' difficulties in returning to earth: Neil Armstrong rather hiding away in a university job, Buzz Aldrin battling demons in LA. In fact, I found this final chapter in many ways the most interesting part of the book, Collins full of disquiet about what the extraordinary venture to the moon might mean, and uncertain of his own future. He died in 2021 aged 90, so lived more than half his life after going to the moon and after writing this book. By the time he wrote it, the Apollo programme had already been cancelled and space travel was being restricted to the relatively parochial orbit of earth.

"As the argument ebbs and flows, I think a couple of points are worth making. First, Apollo 11 was perceived by most Americans as being an end, rather than a beginning, and I think that is a dreadful mistake. Frequently, NASA's PR department is blamed for this, but I don't think NASA could have prevented it." (p. 464)

Collins thinks the American people viewed landing on the moon like any other TV spectacular, akin to the Super Bowl, and so they couldn't then understand the need to repeat it. I'm not sure that's the best analogy given that the Super Bowl is an annual event, but it's intriguing to think of the moon landing as circus. Then again, does that explain the similar loss of interest in the space programme from those outside the US?

I'm more and more interested in the way Apollo was explained and framed for the public at the time...

|

| TV Times listings magazine 19-25 July 1969 "Man on the Moon - ITN takes you all the way" |

- Me on Apollo by Fitch, Baker and Collins

- Me on Ad Astra, An Illustrated Guide to Leaving the Planet by Dallas Campbell

- Me on Moonglow by Michael Chabon

- Me on #Cosmonauts and #OtherWorlds

- "So What If It's All Green Cheese? The Moon on Screen", my essay in the exhibition catalogue accompanying "The Moon" at Royal Museums Greenwich

- "Man on the Moon", my essay on the psychology involved, in medical journal Lancet Psychiatry

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Countdown to the Moon #771

The things I held up at the beginning are:

The Moon - A celebration of our celestial neighbour (ed. Melanie Vandenbrouck, 2019), which accompanied the National Maritime Museum's exhibition The Moon

Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters (2020), in which Dr Who meets early lunar colonists all making the "great leap" in giving up their Earth citizenship. Oh, and some Sontarans.

Sunday, April 25, 2021

The Relentless Moon, by Mary Robinette Kowal

The Lady Astronaut series is set in a world where a meteor smashes into the US in the 1950s, with a dramatic effect on the climate which only looks to get worse. This accelerates the space programme, with the active involvement of women. The first two books in the series are led by Dr Elma York, "the" Lady Astronaut as far as the press are concerned. This new book is focused on one of her colleagues, Nicole Wargin - an accomplished astronaut in her own right but also the wife of the governor of Kansas. He's struggling with the fact that a lot of people object to the expense of the space programme, and many want to deny the existence of the global crisis. An "Earth First" movement is flexing its muscles with ever more menace.

It's a thrilling read, full of incident and twists - the end of Part II in particular made me gasp. The nerdy technical stuff is also threaded with raw emotion: Nicole's anorexia is as much of a wrench for those around her as it is to her. There's grief, too, and the PTSD of those surviving the meteor in the first place, and lots on race and sex (both gender politics and nookie). Lots of this is conveyed in telling detail: an argument where we glean that racial epithets have been used without being told exactly what was said; the mouthfeel of apple sauce or cottage cheese when Nicole is under stress; the chilling etiquette in not asking people where they're from in this world, since it may well have been destroyed.

In her "About the History" notes at the end, Kowal says that in her "LAU", the meteor prevented Jonas Salk working on his polio vaccine which is why the disease is such an issue in the novel.

"The headline about Chicago refusing to vaccinate children? That is real. The vaccination program did work though and brought the polio epidemic to a standstill. The last case of wild polio in the United States was in 1979 ... When I wrote this book, COVID didn't exist. As we go to press ... the choices that I've made to be religious in my social distancing and mask-wearing are directly influenced by the research I did about polio. My father says that he remembers movie theatres being shut down, how no one would get into a public swimming pool, and that 'everyone was afraid of getting it.' Everyone knew someone who had gotten polio." (p. 698)

As well as the disease itself, Kowal deals with denialism, and in Part III there's the horrible, practical issue of a funeral attended over video link. It's a coincidence that it all feels so timely, but it's a testament to Kowal's skill that this stiff feels so credible having now lived such experience.

Other elements of the plot may have been borrowed from fiction. The front cover of my copy includes an endorsement from Andy Weir, author of The Martian, and I think that book might be the inspiration for Nicole making use of stuff left over from previous expeditions. Earlier, the crew of Nicole's moonbase are compromised using the same method deployed by the Cybermen in 1967 Doctor Who story The Moonbase - and I know Kowal has admitted sneaking the Doctor into other books.

But the success of The Relentless Moon is all down to Kowal as expert pilot. For all the thrills and danger, as readers we're in safe hands: the setting and characters grounded in reality, each of the myriad mysteries tied up by the end, the technical stuff balanced with plenty of humour and insight. It's a hugely satisfying read. The epilogue, set two years after the main events, took me completely by surprise but in retrospect seems inevitable, the ground skilfully prepared - so what felt at first like a giant leap is really a small step. And that, I think, is what makes this book so appealing: it's all about small steps forward in dealing with crises. We can work our problems.

- Last year, I took part in an online panel with Mary Robinette Kowal - World-Building: How Science Shapes Science Fiction

Friday, March 05, 2021

Doctor Who Magazine #562

First, in "Moonbase 3" Rhys Williams and I have scrutinised recently discovered studio floor plans for 1967 story The Moonbase, focused on the ingenious way designer Colin Shaw maximised limited space. The CGI recreations of the studio set-up for episode 3 are by clever Gav Rymill. I also got some insight into the kind of person Colin Shaw was from his friend and colleague (and my old boss) John Ainsworth. Thanks to researcher Richard Bignell for alerting me to the discovery of the floor plans and helping my poor old brain make some kind of sense of them.

Secondly, "Sufficient Data" is a new regular column by me (and, from next issue, Steve O'Brien) illustrated by Ben Morris and exploring numbers and concepts in Doctor Who in what we hope will be a fun and surprising way. This issue we're all about the number 13. Steve, Ben and I previously worked together on the book Whographica, which is still available in bookshops.

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Wicked Sisters cover

Big Finish have put up Tom Newsom's amazing cover art for Doctor Who - Wicked Sisters, the trilogy of audio stories I've written that is out in November.

Wicked Sisters stars Peter Davison as the Doctor, Louise Jameson as Leela, Ciara Janson as Abby and Laura Doddington as Zara, with Anjli Mohindra as Captain Riya Nehru and Dan Starkey as the Sontarans. It's directed by Lisa Bowerman and produced by Mark Wright.

ETA The Big Finish website has added a trailer for Wicked Sisters, blurbs for the three stories and a full cast list.

The Doctor is recruited by Leela for a vital mission on behalf of the Time Lords.

Together, they must track down and destroy two god-like beings whose extraordinary powers now threaten all of space and time. These beings are already known to the Doctor.

Their names are Abby and Zara...

1. The Garden of Storms

In pursuit of Abby and Zara, Leela pilots the TARDIS to the eye of a violent storm in time. Yet she and the Doctor find themselves in an idyllic garden city, the people contented and happy. They soon discover that this bliss comes at a terrible cost, and that Abby and Zara are determined to put things right… so how can Leela and the Doctor stop them?

2. The Moonrakers

Life is hard for the early pioneers building the first settlements on the Moon. The laws of Earth don’t apply here, and there are tussles over limited resources vital to survival. Arriving on the Moon, the Doctor and Zara discover that an aggressive alien species lies in wait. Yet there’s something very strange about these particular Sontarans: they refuse to fight.

3. The People Made of Smoke

Abby and Zara strive to use their powers for good but it’s clear they are damaging reality - and allowing monstrous creatures to bleed through from beyond. The Doctor knows he can only save the universe by destroying his friends. But just how much might he be willing to sacrifice if there’s a chance to save them?

Cast:

Peter Davison (The Doctor)

Louise Jameson (Leela)

Ciara Janson (Abby)

Laura Doddington (Zara)

Lisa Bowerman (Smoke Creatures)

Pandora Clifford (Zeeb / Zeet)

Paul Courtenay Hyu (Wei)

Nicky Goldie (Polk)

Tom Mahy (Brody)

Anjli Mohindra (Captain Riya Nehru)

Dan Starkey (Stent / Sontarans)

Saturday, July 11, 2020

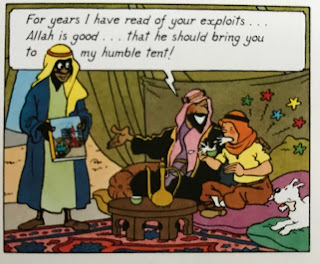

Tintin, by Herge

“That is fraught with difficulty. Where does it stop? I'm reading Tintin with my son at the moment and an exhibition of tolerance it certainly is not. It reads like one long parade of racial cliches.” (Tweet by Amol Rajan, 10 June 2020)

“she turns up in the oddest places: Syldavia, Borduria, the Red Sea… She seems to follows us around!” (p. 13)

“EXTRACT FROM THE LOG BOOK BY PROFESSOR CALCULUS 4th June - 2150 hrs. (G.M.T.) Wolff and I spent the day studying cosmic rays, and making astronomical observations. Our findings have been entered progressively in Special Record Books Nos. I and II. The Captain and Tintin have nearly finished assembling the [reconnaissance] tank.” (p. 98)

Saturday, April 25, 2020

The Fated Sky, by Mary Robinette Kowal

There are all kinds of hazards along the way, including diarrhoea in space - a hundred times more horrible than it sounds - and Earthbound conspiracists attacking their own technological infrastructure in ways that echo recent attacks on 5G. In fact, this tale of people cooped up together for long stretches really resonates just now, the astronauts missing loved ones and unable to do anything about the medical emergencies affected their loved ones back home...

Yet for all the big events and hard science, this is a novel about the little stuff - the interpersonal relationships, the struggle not to be That Arsehole.

"Space always sounds glamorous when I talk about it on television or the radio, but the truth is that we spend most of our time cleaning and doing maintenance." (p. 425).I'm keen for the next instalment, The Relentless Moon, due out later this year, but the author's website includes links to some short stories in the meantime:

Here's the list in internal chronological order:

"We Interrupt This Broadcast"The Calculating Stars"Articulated Restraint"The Fated SkyThe Relentless Moon - coming 2020

The Derivative Base - coming 2022

"The Phobos Experience" - in Fantasy & Science Fiction July 2018"Amara's Giraffe""Rockets Red""The Lady Astronaut of Mars"

Tuesday, April 07, 2020

Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters

It's been a thrill to reunite the Doctor with the leads from my sci-fi series Graceless, and I couldn't be happier with the result. The series stars Peter Davison, Louise Jameson, Ciara Janson and Laura Doddington - plus some amazing guest actors who will be announced in due course.

Full press release as follows:

- The Garden of Storms

- The Moonrakers

- The People Made of Smoke

Producer Mark Wright said: “It’s been ten years since we first took Abby and Zara off on their own adventures, and it’s fun to get the team that’s worked on every episode of Graceless together every couple of years.

Friday, October 11, 2019

The Calculating Stars, by Mary Robinette Kowal

So, despite the devastation the space programme is well ahead. In our universe, the space race began years after this, on 30 August 1955, when lead engineer Sergei Korolev got the Soviet Academy of Sciences to agree a programme to beat the Americans into orbit. The result was Sputnik (4 October 1957), followed by the first person - Gagarin - sent into space, on 12 April 1961. A month later, President Kennedy announced plans to land people on the Moon by the end of the decade.

Part of the joy of The Calculating Stars is how much of "our" history is woven into the alternate timeline: our heroine, Dr Elma York meets Wernher von Braun, while among her fellow trainee astronauts listed on page 426 are "Collins, Aldrin and Armstrong". Her husband reads science-fiction by Ray Bradbury, his visions of settlements on Mars apparently coloured by the events in this timeline.

Also great is the technical detail. We encouter this world through Elma's perspective as a former WASP, a qualified pilot and extremely competent mathematician. She works as a human computer, outperforming the nascent IBM machines - at one extremely tense moment in the story, her speed and accuracy with complex numbers are vital. Robinette Kowal's acknowledgements include real astronauts and other experts: she admits she doesn't understand the maths herself. As a nerd for the early days of space travel, there was lots I recognised - and lots that came as new.

"There is something about having your legs over your head that makes you need to pee. This makes it into none of the press releases, but every single astronaut talks about it." (p. 493)But the book is also excellent on the social detail: the drama of this post-meteorite world is overshadowed by inherent sexism and racism, our Jewish heroine not immune to her own prejudice. Elma also suffers from anxiety and there's lots on the shame and secrecy surrounding mental illness. Characters are well drawn, and Elma must learn to work alongside people she doesn't necessarily like, managing rivalries and her own privilege, for all she is discriminated against. Each chapter opens with a quote from a newspaper filling in more of the background detail of this world, and full of telling turns of phrase. It all makes for a rich and real version of history, a compelling world in which this adventure takes place.

It is an adventure, full of twists and turns. Robinette Kowal nicely manages the personal stakes with the technical and global. I zipped through the almost 500 pages and am keen for the next instalment.

Sunday, August 04, 2019

Doctor Who: The Invasion, by Ian Marter

I’ve looked it up, and that book was originally published on 10 October 1985, not quite 17 years after the TV version was broadcast. It was a window on to ancient history – Doctor Who from before even my elder brother and sister had watched it, so old it had been in black and white. Of course, this was also the closest I ever thought I’d come to seeing the episodes themselves. I’d not yet seen any old Doctor Who on video and there’d been just a handful of repeats on TV. But I knew the photo of the Cybermen outside St Paul’ Cathedral from the Doctor Who Monster Book, and remember the vivid thrill of realising this was that story.

Other bits of the book stuck fast in my memory: the ongoing joke where the Doctor mixes up radio etiquette, or Isobel writing notes on her wall because its harder to lose than a scrap of paper. I’m struck now how much Isobel and Zoe vanish from the first half of the story, their insistence on being involved in the second half feeling a little too late. I also liked Ian Marter’s invention of the Russian rocket base (named after Nicholas Courtney) and the collaboration between US and USSR that’s needed to stop the invasion.

That said, it’s striking how much the novelisation lacks in context of other Doctor Who. How strange to begin with a hanging reference to one of the most extraordinary moments in the series ever, without ever explaining:

“The disintegration of the TARDIS in their previous adventure had been a horrifying experience,” (p. 8.)The novelisation of that previous adventure, The Mind Robber, was not published until 1987 (I never read it, and watched the TV repeat in 1992 with no idea what was about to happen). We’re not told, either, in what context Jamie and Zoe have both met the Cybermen before – for the latter, The Wheel in Space wasn’t published until 1988 – or that Zoe hasn’t already met Lethbridge Stewart.

There’s something strange, too, about referring to this Doctor as “the dapper Time Lord” (p. 11). Dapper isn’t right for this scruffy vagabond of time, and we didn’t learn that he’s a Time Lord until four stories later. (There’s also something odd about referring to him like that anyway, wrote this human.)

Ian Marter is also profligate with adverbs and often he tells us how dialogue is spoken – tersely or sarcastically, gasped or panted – when the words spoken tell us implicitly. But the main thing is how violent this version is.

“The Cyberman’s laser unit emitted a series of blinding flashes and Packer’s body seemed to alternate from positive to negative in the blistering discharge. His uniform erupted into flames and his exposed skin crinkled and fused like melted toffee papers.” (p. 145)If nothing else, Jamie wouldn’t be able to rob the dead Packer of his jacket, which he then wears in The War Games.

(Actor Frazer Hines tells me about that in the Jamie and Second Doctor set from the Doctor Who Figurine Collection.)

Thursday, July 11, 2019

Floating in Space repeat

On Tuesday, I was in the audience at Broadcasting House for the recording of James Burke: Our Man on the Moon, to be broadcast on Radio 4 on 20 July. It's full of great clips - many of them new to me - and Burke presented with characteristic insight, intelligence and wit. It's superb.

Monday, July 01, 2019

Man on the Moon - the psychology of Apollo 11

You need to subscribe to read the whole thing, but here's the opening paragraph:

"In May 1960, Brooks Air Force Base in Texas (USA) hosted a symposium on psychophysiological aspects of space flight. The meeting aimed to present what was known about human behavioural capabilities in space and to recommend directions for further research. It was still relatively early days in the Space Race. The first human ventured into space the following April, and the first American human a month after that. Only then did the American president announce his ambitious plan to land people on the Moon and get them home safely by the end of the decade. But the delegates at the symposium looked boldly forward to the long-term conquest of space, even considering voyages lasting several thousand years..." ("Man on the Moon", Simon Guerrier, The Lancet Psychiatry, Vol. 6, No. 7, pp. 570–572. Published: July 2019.)(I've another essay, "So What If It's All Green Cheese? The Moon on Screen", in the exhibition catalogue accompanying "The Moon" at Royal Museums Greenwich.)

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Arrival of Moon

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

The Moon - A celebration of our celestial neighbour

I've an essay in The Moon - A celebration of our celestial neighbour, a new book edited by Melanie Vandenbrouck.

I've an essay in The Moon - A celebration of our celestial neighbour, a new book edited by Melanie Vandenbrouck. In July it will be 50 years since the first crewed landing on the Moon and this book accompanies the forthcoming major exhibition at Royal Museums Greenwich - where I did my GCSE in astronomy all those years ago. Full blurb as follows:

Official publication for the Royal Museums Greenwich major exhibition The Moon, marking the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s ‘small step’, with the Apollo 11 Moon landing. Written by the Royal Observatory’s leading astronomers and moon experts, this landmark work explores humankind’s fascination with our only natural satellite.

Highly illustrated with 180 fascinating colour and black and white photographs this book is a treasure trove for all amateur and professional Moon watchers.

Sections include:

A constant companion

Learn how we started to observe the Moon, how we used it to mark time and navigate, how lunar lore developed across the world, how the Chinese developed calendars and predicted eclipses. See how the Moon has influenced African art, and also acted as a muse for artists in other parts of the world in a variety of media.

Through the lens

Once the telescope was invented the Moon was observed, drawn and mapped and highly detailed artworks were also created. When photography came along the Moon was an early target until we eventually landed on the Moon surface in July 1969, 50 years ago. Today we can process images of the Moon to show it in extraordinary colour.

Destination moon

We have travelled to the Moon in stories for a long time, using fantastical machines and strange substances. When film arrived we transferred the stories to that medium and the space race was on long before we ever made it in person.

Nevertheless, we have satarized our satellite, we have reported fantastical events in our newspapers and artists have used it as a subject in many different styles of artwork. The Moon and space programmes have also influenced fashion, toys and culture.

For all mankind?

Scientists have investigated what it is made of, how its craters were formed and its origin and great steps have been taken since the Moon landings. Meantime in cinema and television Moon topics continue to appear. Poets have long been influenced by it and this continues today, science fiction is still flourishing. Artists also continue to use new media such as video and others have created a series of works. The Moon has not escaped geopolitics with various treaties being signed in relation to space debris.

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

The Sky at Night Book of the Moon, by Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock

BBC Books (who, I should declare, publish stuff by me) sent me this fun new volume from TV's Dr Maggie, which she herself describes as, "a voyage that has explored the physical, mental and emotional impact of the Moon on all of us."

BBC Books (who, I should declare, publish stuff by me) sent me this fun new volume from TV's Dr Maggie, which she herself describes as, "a voyage that has explored the physical, mental and emotional impact of the Moon on all of us."Much of the collected material is familiar from her BBC Two documentary, Do We Really Need the Moon?, detailing the history of our relationship with the Moon and how it benefits us. For example, its relatively large size stabilises Earth's orbit; it has slowed the spin of the Earth to the 24-hour cycle we're used to; the tides it creates may have played an essential role in the development of the very first life.

There's a lot more science, too - including updates on the latest efforts to return humans to the Moon - but also a selection of favourite Moon-related poetry, art and stories, and an exploration of the oldest Moon-related artefacts. I was captivated by the entry on "En-hedu-ana: Astronomer Princess of the Moon Goodess (c. 2354), who is,

"the first female name recorded in history and the first poet known by name too." (p. 65)On the next page, we're told that at least one of the numerous depictions labelled as En-hedu-ana shows her with a "substantial beard."

I read the book as research for a potential project, and now I have another one...

Tuesday, June 19, 2018

Apollo, by Fitch, Baker and Collins

The comic begins in the moments before launch, and concludes with the Command Module on its way back to Earth. It seems largely told from the freely available NASA transcripts of the flight, and a number of books - including those written by Aldrin and Collins (the astronaut) about their own experiences. We also hear from witnesses at various levels of remove - Armstrong's wife, Aldrin's dad, soldiers out in Vietnam - and skip back in time to formative moments in childhood and the catastrope of Apollo 1.

In addition, there are the astronauts' dreams and nightmares, and I wondered if these were based on things the astronauts themselves reported, or are the invention of the writers. Really, what I'd like are exhaustive endnotes detailing every source, in the manner of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell in From Hell.

The halftone colour, provided by Kris Carter and Jason Candy, suggests the feel of comics from the period, too. Pulpier, less glossy paper and design might have better suggested an authentic artefact of the Apollo age. But this is a sumptuous physical object - which is hardly a criticism, is it?

The comic is good at underlining the dangers involved at each stage of the mission, and reveals plenty of telling detail as the story unfolds - Aldrin's efforts to be the first on the Moon's surface, Nixon's realisation that he'd be remembered as president if the mission failed, Kennedy if it succeeded. There are maybe some things that might have helped with that: Nixon actually recorded the speech mentioned here, to be broadcast in the event that a failure left Armstrong and Aldrin to die, stranded on the Moon's surface (it's included in the amazing documentary, In the Shadow of the Moon). That message may - I've not been able to find enough hard evidence - have been recorded just as Nixon was preparing to make a live phone call to the two astronauts as they bounced around in the moondust. No wonder Nixon was sweating during that call...

That's a minor quibble; this is an absorbing, detailed and arresting account that manages to bring something new to the so thoroughly picked over story. I shall be sure to pick over it again during the coming 12 months, in the lead up to the 50th anniversary of that first Moon landing.