Basically, they're vignettes from all round the capital, edited versions of Morton's column for the Daily Express. He visits Big Ben, goes back stage at the Old Vic, sits on more than one night-time riverboat on the look-out for suicides. There are flea markets and dances, a tour of the Royal Mint, a boxing match, a gambling den and much more. At one point, he's in the tower at Croydon Aerodrome, gazing across the Surrey fields to the twin towers of Crystal Palace - and somewhere in between, my old home.

At his best, Morton has access and insight so that it feels authoritative. Quite often, though, he gives full rein to whimsy, allowing himself to imagine the conversations - the whole lives - of people he merely glimpsed in passing, many of them salt-of-the-earth Londoners he names "Alf". More than once I was left thinking, 'But how could you know this?' or 'How could you have overheard?', so it lacks the authenticity of my friend Miranda Keeling's observations of real life.

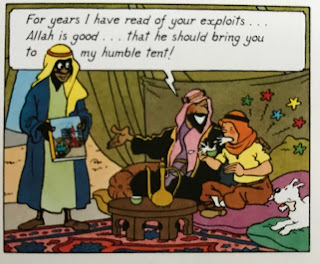

At worst, Morton is misogynist and racist. His wandering eye falls, for example, on a pretty girl, but he assumes she is Jewish and will therefore soon grow fat. Another time, he describes the Chinese community in Limehouse as monkeys and is baffled by evidence that the men might be good to their wives. They allow him into their homes and bars; the threat of violence is all imposed by Morton. All of this stated quite openly, and shared in the popular press. It's not merely shocking; it is not the London I know.

Morton's is a strikingly dirty and polluted London, full of junk markets and rag fairs, worthless rubbish even sold from the windowsills and steps of the crumbling tenements. Almost every description of a landmark is shrouded in mist. One particular smog comprises,

“Many flavours. At Marble Arch I meet a delicate after-taste like melon; at Ludgate Hill I taste coke. … Everywhere the fog grips the throat and sets the eye watering. It puts out clammy fingers that touch the ears and give the hands a ghostly grip.” (p. 25)

The landmarks, too, are sooty. Viewed from the clock tower that houses Big Ben, he spies Nelson's column,

"stood up jet black like a cairn above the mist of a mountain top" (p. 160).

This juxtaposition of the modern and the mythic is a favourite trick of Morton's - wowed by a room in which Dickens once stood, or sounds that might have been familiar to Romans. It can get a little repetitive and yet his interest in the ancients can often provoke his most evocative writing, such as this from a visit to Cleopatra's Needle:

"Did you know that beneath the famous stone is buried a kind of Victorian Tutankamun’s treasure, placed there to give some man of the future an idea of us and our times? Did you realise that the London municipal authorities could do anything so touching? … In 1878 sealed jars were placed under the obelisk containing a man’s lounge suit, the complete dress and vanities of a woman of fashion, illustrated papers, Bibles in many languages children’s toys, a razor, cigars, photographs of the most beautiful women of Victorian England, and a complete set of coinage from a farthing to five pounds. So the most ancient monument in London stands guard over this modernity, rather like an experienced old hen, waiting for Time to hatch it.” (p. 78)

Again, he can't resist playing this against aching modernity:

"I stood there with the tramcars speeding past and the criss-cross traffic," (p. 79).

But it's a spot I know very well, and those tramcars are from a lost world.

In describing how omnibuses have changed within his own memory, Morton reveals what else is different (as well as his usual predilection for women's underthings):

“In 1925, when this was written, London omnibuses had open roofs, and the seats were protected by black tarpaulin covers which travellers could adjust in wet weather. Nowadays the London omnibus is an enclosed juggernaut and wet seats are things of the primitive past. Also, the Strand has changed since 1925. It has been widened in parts, and it is no longer an exclusively masculine street. Silk stockings are probably now more in evidence there than pith helmets and spine pads [from the imperial outfitters].” (p. 34n)

This throng of Londoners heading out into the Empire he finds straightforwardly heroic, but anything of that world coming into London is straightforwardly threatening. In Morton's view, all foreigners are at best suspect; often they're also monstrous. Then, while out on the Thames at 2 am, he spots, “a queer fleet at anchor” in Limehouse:

“‘The smallpox boats,’ said the sergeant [giving him this tour]. ‘They are always fitted up ready to take patients [arriving in ships] down to the isolation hospital in the event of any outbreak.’” (p. 400)

It's not as if the capital is otherwise a bastion of good health. There are no gyms or joggers in this London. Morton's description of conditions in the few free hospitals in a time pre-NHS is gruelling, for all he admires the good-hearted people running such charity. He also visits St Martin's by Trafalgar Square, where the homeless men offered shelter are divided into three types: ex-prisoners with a grudge against the world; those who won't work; and,

"those who went to the war as boys and came back men with boys’ minds" (pp. 42-43).

"A parcels delivery boy riding a tricycle van takes off his worn cap [as he passes]. An omnibus goes by. The men lift their hats. Men passing with papers and documents under their arms, attache and despatch cases in their hands—and the business of life—bare their heads as they hurry by." (p. 19)

That's all the more poignant given when this edition was compiled. Morton's first introduction to these three books was written in August 1940, addressing fellow imperilled Londoners. His theme is the pride and interest the Second World War has ignited in their city as it faces devastation.

"Men who in former years hardly knew where their town hall was to be found, now sleep there regularly, and have become familiar with many a municipal mystery. Men and women, to whom a fire hydrant was once a technical term which cropped up occasionally in the newspapers, can now draw you an accurate map of the water-supply of their district. Countless diligent wardens know by heart streets which, until recently were an untracked wilderness to them, although they lived just round the corner." (p. vii)

A second introduction, written in February 1941, is for American readers. London, he informs them gravely,

“has experienced the mass raid; the single nuisance raider; the high explosive raid; the fire raid; the mixed h.e. and fire raid; the raid directed against docks and warehouses; and the raid directed, apparently, against Wren churches and hospitals.”

But there are broadly two types of air raid: day and night.

“When London is raided by day, people no longer rush into shelters and cellars at the first note of the siren, as they used to when they were new to bombing.” (p. viii)

Instead, Londoners look around for signs of alarm or haste, but the traffic otherwise continues. Yet, hyper-vigilant to all sounds and senses, they will suddenly scatter. Night raids are another matter - altogether more tense and exhausting, even before the bombs come.

"As darkness approaches people become restless and begin to think of getting home before the black-out. Shops and businesses close early in anticipation of ‘siren time.’ Dusk falls, and the streets empty. It is not a pleasant experience to stand, say, in Bond Street, the pavements deserted except for anxious groups round the bus stops, every taxi-cab either occupied or else driven by a man who cannot take you back where you wish to go because he is himself trying to race the black-out to the other side of London." (p. ix)

"The task of such civilians in war is infinitely more difficult than that of the soldier, who is a single-minded man trained to fight with others and untrammelled by any struggle to maintain the normalities. … Most gallant, and tragic, are those others who have been bombed out of flats and houses, some of them losing everything they possessed. The ability to ‘double-up’ with relatives and friends in times of misfortune, formerly an exclusive habit of the poorest classes, is now a general tendency. Admiration for those who have no homes, who spend their nights in other people’s shelters, and turn up at their offices in the morning to carry on as usual, is beyond expression.” (p. xix)

"The result [of the Blitz] is a grim city, a shabby city, a scarred city, but not a devastated city, except round and about Guildhall, where several famous streets have been burned to the ground.” (p. x)