It's a fascinating story of a fascinating life. Highsmith is a complex, contradictory subject - on several occasions we're given completely different accounts of her, by turns cruel or kind, quiet or outspoken, fearful or bold. There are lots of reasons not to like her - the racism, the snobbery, the meanness with money when she was so wealthy. Yet understanding her background, her relationship (or lack of it) with her mother and her various struggles and heartbreaks makes this a compelling read.

There are all kinds of odd, striking moments. As well as the snails, there's her short-lived relationship with Tabea Blumenschein,

"the 25 year-old star and producer of the lesbian avant-garde pirate adventure Madame X" (p. 366).

Highsmith and Blumenschein spent six days together in a flat in Pelham Crescent, South Kensington, in May 1978 and at one point browsed the record shops. Blumenschein told Wilson that,

"Pat bought me the Stiff Little Fingers record" (p. 367),

presumably the band's debut single "Suspect Device" (released 4 February that year), before they went to dine with Arthur Koestler. The incongruity of that is even more striking when compared to Highsmith's selection the following year for Desert Island Discs: Bach (twice), Mahler and Mozart, and George Shearing's "Lullaby of Birdland".

A number of things made me begin to suspect that Highsmith was neurodiverse, and late on in the book her friend and neighbour Vivien De Bernardi told Wilson,

"In hindsight, I think Pat could have had a form of high-functioning Asperger's Syndrome. She had a lot of typical traits. She had a terrible sense of direction ... She was hypersensitive to sound and had these communication difficulties. Most of us screen certain things, but she would spit out everything she thought. She was not aware of the nuances of conversation and she didn't realise when she had hurt other people," (p. 394).

De Bernardi said this explains why Highsmith's relationships did not last; I think that's a bit glib - and that Highsmith may also have had some kind of attachment disorder, not helped by her (lack of) relationship with her mother. But I'm struck by De Bernardi's perspective of how this neurodiversity impacted Highsmith the writer:

"Although she didn't really understand other people - she had such a strange interior world - she was a fantastic observer. She would see things that an average person would never experience," (ibid).

Wilson has much to say about the content of and responses to Highsmith's lesbian novel The Price of Salt (1952), later republished as Carol and adapted into the acclaimed film. Highsmith originally published the book under a pseudonym and even when it went out in her own name was guarded in interviews about her sexuality. Often, people who knew Highsmith speak of her attitude to women as if from an outside perspective - as if she were a man. Wilson quotes Highsmith's own cahiers (notebooks) at great length, including a passage from 1942 that is ostensibly about other women and yet surely about herself.

"The Lesbian, the classic Lesbian, never seeks her equal. She is ... the soi-disant [self-styled] male, who does not expect his match in his mate, who would rather use her as the base-on-the-earth which he can never be," (p. 48, quoting Highsmith's Cahier 8, 11/18/42, Swiss Literary Archives in Berne).

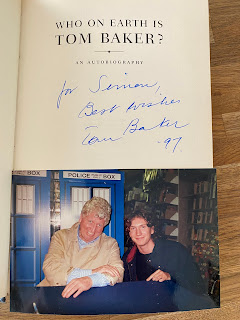

Repeatedly, Highsmith identified with her most famous fictional creation Tom Ripley, signing a copy of Ripley Under Ground for her friend Charles Latimer as "from Tom (Pat)," (p. 194, but see pp. 194-6, 199, 350 and 454 for further examples). I now want to reread The Talented Mr Ripley (1955) with all this stuff in mind - from a queer (in the sense of both "strange" and "homosexual"), autistic, trans perspective. It's a book about somebody wanting to be and transforming themselves into someone else; an act of disguise that I think, having read this biography, might be very revealing.

.jpg)