Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Telescope cherry

My astronomy GCSE course has attempted this before, and again last night we trooped up to the famous 28" inch refracting telescope (the one used by Karen Gillan in Doctor Who Confidential earlier this year) only to find the view again obscured by clouds. The proper astronomer and our teacher filled time, explaining the history and mechanisms and testing our new-learnt knowledge. We waited and waited, and used a clever gadget called a 'window' to check if the sky might be clearing, but eventually decided to troop back into the warm.

Once we'd watched the telescope get put to bed and trooped down the steps and outside the Moon couldn't have been clearer - the tease. So the intrepid Nick who organises our group quickly found us an 8" inch reflector built by Meade: a bucket-shaped thing about the length of my forearm.

As the experts put this contraption together, Nimbos and grabbed a cup of tea and were then out in the cold again to queue up for a look.

The waxing gibbous moon looked shiny bright to the naked eye and, as thin cloud occasionally brushed over it, produced a glowing halo. This is due to icy crystals in the wintry cold atmosphere, which refract moonlight. The centre of the halo is bluish, the edge of it red - for the same reason as the different colours of the rainbow.

Looking through the telescope was something else entirely. At first I could see nothing but a white blur - as we'd been queuing the Earth's rotation had moved the telescope a bit. The helpful astronomer adjusted the setting and then - oh blimey - I saw.

A curved, gleaming surface of white, splotched with little craters, so bright it looked like plaster of Paris that had not quite set, the splotches made just a moment before I looked. The edges of these feature cast long, distinct shadows, picking out the details. The surface rippled slightly, as if I was looking through clear water - an effect of Earth's atmosphere refracting the light, something astronomers call 'seeing'. But another world, and in plain sight, tantalising, just out of reach.

Once we'd all wowed at this incredible view, the astronomers moved the telescope and trained it on Jupiter. With the naked eye, the huge planet looked like a bright star, hanging at about five o'clock below the Moon. Before we'd ventured out into the cold, we'd look at it using the free - and cool - Stellarium software which gave us an idea of what to expect: Jupiter in a line with its four largest moons.

But to actually see it! I took a moment to realise what I was looking at - the telescope flipping the image upside down, a reflection of the Stellarium cheat. A murky, stripey ball hanging in the darkness at the centre of the eyepiece. To the left (in reality, to the right) three bright stars - just the same size as Jupiter appeared to the naked eye. On the right, another star.

These moons, first seen by Galileo 400 years ago, transformed our understanding of our place in the universe. For more than 2,000 years the assumption had been that the Earth was at the centre of everything, that the celestial bodies looped slowly around us. Galileo tracked the positions of his four Galilean moons and showed why they moved and sometimes vanished. Now here was evidence of Moons circling something else: proof that we're not at the centre of things, the first sign that we live and toil on an insignificant sticky rock circling an insignificant star.

That is, except for something that's not insignificant: we look up.

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Meat feast

Friday, November 05, 2010

Where's Simon?

Graceless, the three CD sci-fi mini-series what I wrote, is out this month. The Big Finish website boasts full details and a trailer, and the new issue of free online Vortex magazine interviews stars Ciara Janson and Laura Doddington.

Graceless, the three CD sci-fi mini-series what I wrote, is out this month. The Big Finish website boasts full details and a trailer, and the new issue of free online Vortex magazine interviews stars Ciara Janson and Laura Doddington.Ciara will also be at the Dimensions convention next week, along with director Lisa Bowerman and the Big Finish gang. Me, Ciara, Lisa, Laura and a whole cohort of slebs will also be at ChicagoTARDIS at the end of the month. Hooray!

That sadly means I miss Nev Fountain and Nicola Bryant signing copies of the Mervyn Stone Mysteries at Forbidden Planet on 25 November. The books are now out and already garnering nice comments on the internet. I've been helping with the publicity.

Also out now is Cinema Futura, edited by Mark Morris and containing the wise words of many wise people, including my chums Guy Adams, Paul Cornell, Joseph Lidster, James Moran and Rob Shearman. Oh, and there's me going on about the Peter Cushing Doctor Who films.

Plus I've got a story in the new Bernice Summerfield anthology, Present Danger, edited by Eddie Robson. It's the first thing I've written for dear old Benny in three years - back when I was her boss and king.

I'm afraid there's a load more of stuff by me due out over the next few months. Prison in Space, my adaptation of an unmade 1968 Doctor Who story, is out in December (there's a trailer on the site, too). In January, there's The Perpetual Bond starring Peter Purves and Tom Allen, and a whole bunch of Doctor Who DVD documentaries with my name on the credits. Sorry.

I am, meanwhile, manically busy with a whole bunch of stuff. I'm very nearly done on one extremely thrilling project which I've been slaving on for over a year. Announcements and things in due course. Am also having a lovely time at Doctor Who Adventures, am writing comics and short stories for somebody else and am just about keeping up with my space homework. But phew, knackered. Back to work...

Wednesday, November 03, 2010

Books finished, October 2010

High Rise by JG Ballard is told from the point of view of three men living at different levels of a block going to war with itself.

It's set in a grim future familiar from early 70s films – people living surrounded by concrete and fab gadgets, but where women still know their place and wait for husbands to come back from the office. Like the grim futures of Escape From The Planet of the Apes or A Clockwork Orange, violence seethes barely out of sight of their thick make-up and dinner parties, and suddenly the most respectable figures – think Margot and Jerry Leadbetter – are peeing in the swimming pool, murdering dogs, and caught up in cannibalism and incest.

It's a depressingly cruel and stupid story, playing out scenes of ever more brutal, primal violence in a dispassionate tone. There's little to differentiate our three protagonists apart from the levels at which they live in the building. There's little wit, irony or insight, and a lot of mention of exposed breasts and heavy loins. And yet its easy to get caught up in the collapse, the infantile misanthropy really striking a chord as I read it squodged in among other commuting livestock.

The book also includes various snippets of review, including the following gem:

“Ballard is neither believable or unbelievable ... his characterization is merely a matter of “roles” and his situations merely a matter of “context”: he is abstract, at once totally humourless and entirely unserious...”That sounds rather damning until the next sentence:

“The point of his visions is to provide him with imagery, with opportunities to write well, and this seems to me to be the only intelligible way of getting the hang of his fiction.”'Unbelievable, humourless, abstract... and this is him writing well.Martin Amis, New Statesman, quoted in JG Ballard, High Rise, p. 1.

I read Robert Rogers and Rhodri Walters' How Parliament Works (6th edition) in preparation for a job interview. It's a comprehensive, insiders' account and nicely up-to-date (to 2006), with some good thoughts on the future of the Houses and their procedures which stood me in good stead. I got the job, so woot.

“Long experience has taught me this about the status of mankind with regard to matters requiring thought: the less people know and understand about them, the more positively they attempt to argue concerning them; while on the other hand, to know and understand a multitude of things renders men cautious in passing judgement upon any of them.”Galileo's Dream is a decidedly odd book. About half of it is a historical novel about Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), from his first hearing about the invention of telescopes and endeavouring to build one himself, through to his death under house arrest for daring to suggest, via the evidence of his observations, that the Earth orbits round the Sun.

Robinson is, as ever, expert at explaining the science bits and making them a vivid, thrilling part of the story. He's good at the petty jealousies and court politics that surround Galileo, his struggles with his family and commitments, his need to get funding for his work. It never quite needs be spelled out how little the practicalities of research have changed since Galileo's time.

A lot of this is especially enthralling as I'm studying GCSE Astronomy, and was making my own steady progress through the mathematics of lenses and focal lengths at roughly the same rate as the book. There's some interesting stuff about Galileo, the first man ever to gaze at the magnified moon, drawing prominent features bigger than they really are so that future observers would look out for them (p. 38). Observation, he realises in the book, is itself a level of magnification.

Robinson has a knack for getting into the heads of especially clever people. Galileo himself is a richly drawn character, brilliant and bombastic and impetuous. He makes a lot of enemies early on by winning debates rather rudely and not sparing egos. He's blind to how his actions affect others, estranged from family and former lovers. This all set up his enemies' revenge when they accuse of him of being a heretic.

“Galileo kept defending himself, in print and in person ... Whenever he was healthy he begged Cosimo, through his secretary Curzio Pecchena, to be allowed to go to Rome so that he could defend himself. He was still confident that he could demonstrate the truth of the Copernican hypothesis to anyone he spoke to in person. Picchena was not the only one who doubted this. Winning all those banquet debates had apparently caused Galileo to think that argument was how things were settled in the world. Unfortunately this is never how it happens.”Robinson is again good at teasing out the characters and global politics involved, as the new and liberal Pope finds himself undermined by the Medicis and needing to look strong. A war between two Catholic nations is deftly shown to play it's part in bringing Galileo to trial, while we hear of secret documents and meetings long before they play their part in the story.Ibid., p. 153.

The trial itself is, I think, a major stain on the history of the Catholic Church, but Robinson shows admirable restraint in depicting the many pressures on those involved. I expected the final judgement to make me angry; it just left me sad. The last part of the book, as Galileo struggles against infirmity and the deaths of loved ones, make this an effective tragedy. As a historical novel, it's quite a treat: clever, compelling and moving while at the same time an education.

And yet, that's only half the book. For the other half, Galileo travels epileptically (p.235) to the distant future, where humans are busy bothering alien life on Jupiter's moons – the very moons Galileo was first to see. This allows some rather po-faced future people to comment on and contextualise Galileo and his times, muttering about his treatment of women and his role as the inventor – and first martyr - of scientific method.

It's a little like the trick of Life on Mars, where adding a present-day policeman to a 1970s precinct lets you do all that fun cop stuff like out of The Sweeney while tutting at its prejudice and clichés. But I sighed inwardly every time we jumped to the future for another interminable debate about whether we ought to make contact, or if it would have been better for society had Galileo been burnt at the stake.

There's lots on the development of science after Galileo's – and our own – time. He is brought to the future by something called entanglement which is couched in scientific terms. But this made-up science and the made-up future politics do nothing but disservice to the real man and his accomplishments. The book suggests Galileo – and also Archimedes – achieved great things because of what time travellers had told him. It's an insult to the man and his work, otherwise brought so vividly to life.

We discover that the story is being narrated by the Wandering Jew, himself a traveller from the far future, and telling the story as he awaits execution during the Reign of Terror. It's all in highly questionable taste, and is less profound or insightful as it is portentous. It reminded me too often of dreary sci-fi shows in which dreary characters plod dreary corridors earnestly discussing dreary plot. It's a not very good episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, or any episode of the new Battlestar Gallactica. And this is all the more galling because the other half of the book is so good.

I found John Osborne's Look Back in Anger gruelling when I read it at sixth-form half my life ago. Now it just seems painfully arch, two well-to-do young women falling for the same frustrated loser. It reminded me most of angry tirades from my fellow writers about the world failing to provide for their needs. It's not that I don't do that myself from time to time (sorry), but it's no fun to sit through and not exactly profound. The women - and the audience - would be better off walking out.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Sci-Fi Ancient Egypt

(Will add more images and links when I have a chance.)

“With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same.”

“The man who knows and dwells in history adds a new dimension to his existence; he no longer lives in the one plane of present ways and thoughts, he lives in the whole space of life, past and present, and dimly future. He sees the present narrow line of existence, momentarily fluctuating, as one stage like innumerable other stages that have each been the all-important present to the short-sighted people of their own day”.

“The point of archaeology is to carefully recover the past, not disintegrate it.”

SPHINX

1. UC14769 (IC13, 2nd from top): Part of base of a sandstone sphinx with 2 paws and cartouches each side denoting Seti I.

As Petrie argued, understanding the past helps to place the worries and wants of the present day in context. Archaeology strives to understand the past from the meagre fragments left to us. From the exquisitely crafted jewels and sculptures to the shards of broken pottery, collecting and comparing these fragments slowly brings the long dead back to life.

We know the fragment here shows the paws of a sphinx from comparison with other artefacts and sources. A sphinx is a mythological creature, often (though not always) having the body of a lioness and the head of a woman. Sphinxes are usually found “guarding” royal tombs.

Science fiction can also place the worries and wants of the present day in context by imagining things to come. HG Wells wrote what many consider the first science-fiction novel The Time Machine in 1895 when the British Empire reached across the world.

In the story, a Victorian inventor travels to the year 802,701 where he discovers that humans have died out. Instead, creatures called Eloi and Morlocks live in the shadow of an ancient monument, the only visible remaining trace of civilisation. Wells makes this ancient monument a sphinx, likening the fall of civilisation (and the British Empire) to the fall of ancient empires such as Egypt. The story – and these fragments of two paws – remind us that nothing lasts forever.

Several science-fiction stories show us future societies struggling to understand the fragments left of our own civilisation – often for comic effect. In the 2005 Doctor Who story The End of the World, for example, the Lady Cassandra insists that an old Wurlitzer jukebox is an ‘iPod’.

But there's a sadder connection between the fragments of the past and science fiction. The Petrie Museum holds scant fragments of one of the earliest-known copies of The Iliad. Doctor Who visited the events of The Iliad in the 1965 story The Myth Makers, a story that has since been deleted from the BBC archive. Fragments are left: a full soundtrack (released on CD by BBC Audio), some photographs from the set and a few seconds of low-quality footage.

RAT TRAP

2. UC16773 (Object by Site: Lahun, bottom): Pottery rat trap. Handle, one end and trap door missing - one enlarged air slit partly blocked with ancient plaster. (Originally identified as a coop for small chickens or incubator).

Archaeology and science fiction can both show us how similar we are today to the people of the distant past and future, with the same worries and wants. Here is a pottery rat trap from 1985 -1795 BCE. It gives a vivid sense of the kind of everyday problems faced by people 4,000 years ago. Beside the rat trap is a modern version of the type still in use across Africa. The suggestion might be that little has changed in all that time, that people will always be people. This can also be used to dramatic effect.

In the 2008 Doctor Who story The Fires of Pompeii, Caecillius is pretentious about art, worries about his son getting drunk and how his daughter is dressed. Though this is jokey to begin with, when the volcano Vesuvius erupts, the story is all the more effecting because we've seen these people are so like us.

In The Fires of Pompeii, the Doctor mentions meeting the Emperor Nero – as he does in the 1964 story The Romans. 3. Nero is named in the cartouche on the blocks UC14528 and 16516 (case IC16).

MINOTAUR and MEDUSA

4. UC14518 (case IC9): Limestone slab with bull-headed god, between parts of 2 other figures.

We tend to think of ancient civilisations existing in isolation – the ancient Greeks and Romans separate from the ancient Egyptians. But it's evident from finds made by archaeologists that ancient cultures traded with one another, and that ideas and stories spread. Myths were retold and reworked by different people, as they have been ever since.

Gene Wolfe's Soldier of Sidion (2006) is set in Ptolemaic Egypt, the third in a series about a Roman mercenary making his way through the ancient world but one where the ancient gods walk among the ordinary mortals. A rich, clever adventure, it dares suggest itself less “fantasy” as historical novel.

In the examples on display in the museum here, we can see that the ancient Egyptians themselves told stories featuring characters we traditionally think of as “belonging” to other cultures – such as bull-headed people (like the Minotaur from Greek mythology) and gorgons (like Medusa).

Many science fiction stories rework myths or elements of them. They might reveal that the gods and monsters of the ancient world were aliens or robots. They retell the ancient stories in space instead of Egypt or cherry-pick incidents or characters.

5. UC48468 (case PC 35): Terracotta medallion of a gorgon head; there are traces of white paint on the surface. The facial features are sharply moulded and the hair wavy with two entwined snakes at the top.

Medusa appears in the Doctor Who story The Mind Robber (1968), the Minotaur in The Time Monster (1972). The latter was released on DVD in March 2010 as part of the “Myths and Legends” box-set (BBC DVD 2851), along with two other Doctor Who stories that rework ancient stories.

SOUNDS FAMILIAR

Sometimes science fiction doesn't rework the myths so much as just borrow the names. For example, the Doctor and the Daleks briefly visit the pyramids in episodes 9 and 10 of The Daleks' Masterplan (1966).

(Episode 9 no longer exists in the BBC archive but episode 10 is included in the "Lost in Time" box-set, along with the few existing seconds of footage from The Myth Makers).

The three Egyptians who help fight the Daleks are named “Khephren”, “Tuthmos” and “Hyksos”.

Khephren takes his name from Chephren / Khafre (c.2558 - c.2532 BCE), the pharaoh who built the second great pyramid at Giza and whose face was the model for the sphinx that guards it. You can see a cuboid fragment from the second pyramid at 6. UC16043 (entrance case on right).

Tuthmos is derived from “Tuthmosis”, the name of several pharaohs in the 16th and 15th centuries BCE. Most notably, Tuthmosis III (1479 – 1425 BCE) was a military genius who massively expanded the Egyptian empire. A cartouche of his name can be seen at 7. UC14542 (case IC5).

The tomb of Tuthmosis III was excavated in 1898 by Petrie's contemporary, Victor Loret (1859-1946). The tomb (KV34) in the Valley of Kings included the first complete-found “Amduat” - the book of the Underworld. It is also, as Sarah Jane Smith tells the Doctor in the 1975 story The Pyramids of Mars, where an account is given of Sutekh's battle with his brother Horus.

Hyksos is named after the people from Palestine who ruled in Egypt in the 17th century BCE. Examples of pottery from their time and influenced by them include the black duck jug at 8. UC13479 (case PC27), with white incisions on display in the Pottery Gallery.

SEQUENCE DATING

The film and TV series Stargate (1994, 1997- ) explain that the myths and names of ancient Egypt derive from meetings (via gateways across space) with aliens. The hero of the film is an archaeologist and sarcophagi are used to resurrect people. In the film, the planet on the far side of the stargate is called Abydos, which is the name of the place where the tomb of Osiris is located and where this limestone stele 9. UC14488 (case IC2) was found.

The film shows us the “real” Egyptian gods Anubis and Ra. The TV series has also shown Apophis, Anubis, Ba'al, Hathor, Nirrti, Osiris and Seth – among others. It has also freely used names and events from other mythologies.

(By comparing the names and events of other mythologies rather than Egypt specifically, Stargate follows in a tradition of science fiction stories taking their cue from Joseph Campbell's 1949 book on comparative anthropology, The Hero With a Thousand Faces.)

The stargates and other technology in the series are made of an element called “naqahdah”. The name is reminiscent of Naqada, a town on the west bank of the Nile that Petrie excavated in 1894.

Whereas some archaeologists before him had been more interested in finding treasure and texts, Petrie carefully recorded everything he found, including the broken pieces of pottery on display in the Pottery Room. (Start at PC3 and also see www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/pottery/seqdates.html)

By comparing the styles of pottery itself and its decoration, Petrie developed a Sequence Dating system – a timeline of nine developments in Egyptian pottery. This could then be used to give approximate dates to any further finds made which contained fragments of pottery.

According to Petrie's system – and subsequent testing – the town of Naqada is one of the oldest in Egypt, with pottery found from 4000 BCE in the pre-dynastic period. As a result, the name of the town often appears near the top of any timeline. That may well be why the producers of Stargate chose it.

Like Stargate, a 2009 episode of the TV series Primeval suggested that the “gods” from ancient Egypt were real creatures. One of them chased through the Egyptian galleries at the British Museum.

SCARAB BEETLES

10. UC69860 winged scarab beetle (case L)

The way that scarab beetles rolled great balls of dung seemed, to the ancient Egyptians, like the way the Sun rolled across the sky. Perhaps the Sun, too, was pushed by a giant beetle. The beetle was therefore symbolic of time.

The beetles also ate the balls of dung and their young emerged from them – as if, the ancient Egyptians thought, they had been spontaneously created. The beetles were therefore also symbolic of regeneration.

Time and regeneration are, of course, quite important to Doctor Who. But beetles usually play a more sinister role in modern stories that loot the relics of ancient Egypt. In the 1999 film The Mummy, the tomb of Imhotep is guarded by flesh-eating scarabs.

The 1967 Doctor Who story The Tomb of the Cybermen reworks many familiar elements from Mummy stories in a science-fiction context. In the 1959 Hammer film The Mummy, actor George Pastell plays Mehemet Bey, worshipper of Karnak, who pretends to be a friend of the archaeologists then entreats the risen Mummy to kill them. In the Doctor Who story Pastell plays much the same part, but here he's a member of the Brotherhood of Logicians. Instead of scarabs, we are introduced to Cybermats, which poison and kill the archaeologists as the story requires.

The 1967 Doctor Who story The Tomb of the Cybermen reworks many familiar elements from Mummy stories in a science-fiction context. In the 1959 Hammer film The Mummy, actor George Pastell plays Mehemet Bey, worshipper of Karnak, who pretends to be a friend of the archaeologists then entreats the risen Mummy to kill them. In the Doctor Who story Pastell plays much the same part, but here he's a member of the Brotherhood of Logicians. Instead of scarabs, we are introduced to Cybermats, which poison and kill the archaeologists as the story requires.ANKH

11. UC43949 (case WEC9) Light green faience ankh inscribed on both sides of shaft with epithets and cartouches of Aspelta.

Egyptian gods are often shown carrying the ankh, also known as the “key of life”, the hieroglyphic symbol for eternal life. There are several different theories about what the ankh derives from. Is it meant to show a man and woman united under the Sun, or does it show the Nile at the centre of Egypt, the loop at the top representing the Nile Delta, or a penis sheath?

In Neil Gaiman's award-winning Sandman comics, the ankh is the symbol of the character Death. In the TV series Lost, several characters are seen wearing ankh pendants, while the giant statue of the hippo-god Taweret holds an ankh in each hand. (Lost is littered with Egyptian symbols and hieroglyphs, see http://lostpedia.wikia.com/wiki/Hieroglyphs.)

NEMES HEADRESS

12. UC14363 (case IC17) Head of mottled diroite (about 1/2 size) of King Amenemhat III, wearing Nemes head-dress and uraeus.

The distinctive striped “nemes” head cloth was worn by Egyptian pharaohs. The flaps of the head cloth taper out behind the wearer's ears and hang down below both shoulders. The golden mask of Tutankhamun and the great statues of Ramesses II are famous examples of pharaohs wearing the nemes. It was often worn with a “uraeus” or “cobra” on the forehead, symbol of royalty.

The space helmets worn by Viper pilots in the original Battlestar Galactica TV series (1978-9) were based on the nemes head cloth, subtly suggesting the links between the human refugees seen in the series and the “legendary” planet Earth they were searching for. The helmets featured a viper symbol instead of the uraeus.

The modern version of Battlestar Galactica (2004- ) has not retained the nemes-style helmets, but there are still occasional hints of the links between the refugees and Earth's ancient civilisations. For example, pyramids can be glimpsed on the colony planet Kobol.

Both the original and modern versions of Battlestar Galactica are available to buy on DVD.

MAGIC

13. UC36314 (case J): Hippopotamus ivory clapper, reconstructed from fragments, in form of right hand; incised bracelet band at wrist and ornate net pattern on arm.

There are many theories about the wands found, usually made of hippopotamus ivory. Hippopotamuses and elephants are dangerous creatures, so acquiring the ivory from a living animal may have been part of the ritual. The wands do not use all of the tusk, either, so each tusk may have produced a “family” of linked wands (not dissimilar to the families of wands in Harry Potter). Wands were clearly of great value. Some use ebony and other precious materials.

Little is known of Egyptian magic, which makes it ripe for speculation in horror and science fiction stories. The Book of the Dead is central to many stories dealing with mummies and resurrection. But Egyptian magic is also used to time travel in both Tim Powers' award-winning The Anubis Gates (1983) and Terry Pratchett's less serious Pyramids (1989).

SUTEKH

14. UC45093 (case IC7): Upper part of a green glazed steatite round-topped plaque incised with image of Seth standing, to his right a column of hieroglyphs 'excellent praised one, beloved of Seth lord of Nubt'.

In the 1975 Doctor Who story The Pyramids of Mars, the Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith battle the Egyptian god Sutekh – also known as Set or Seth. The inscription says that Seth was “Lord of Nubt”, the ancient name for Naqara (see above).

Though Seth was Lord of Nubt, the opening shot of The Pyramids of Mars uses stock footage of the step pyramid at Saqqara. A block, possibly an altar or the top of a pyramid looks like the Step Pyramid in Stonework: Statuary IC15 15. UC69838.

Sarah knows about Sutekh's battles with his brother Horus: she explains Sutekh was captured by Horus and “the 740 gods named on the tomb of Tuthmosis III”.

The story includes robot mummies, sarcophagi that transport people, a forcefield controlled by canopic jars, and sphinx-like riddles to get into the pyramid on Mars. It draws heavily on the 1959 Hammer film The Mummy, as did The Tomb of the Cybermen (see above).

While Egyptian mythology (and Doctor Who) is full of creatures that are human but for animal heads, unusually, the animal that provides Seth with his head is unknown to science.

HEROES

16. Portrait of Flinders Petrie by Fülöp László (1934). The old man in the picture might not seem a likely inspiration for Indiana Jones. Yet the traveller-archaeologists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries told exciting tales of the worlds they'd discovered – and the adventures they had in discovering them.

Indiana Jones, Rick O'Connell in The Mummy, Daniel Jackson in Stargate and the Doctor's future wife, River Song in Doctor Who have followed that lead. The archaeologist battles the odds to uncover strange and surprising artefacts that change how we see our own place and time.

Like detectives, they use the clues left behind (17. UC50615 Roman Terracotta Tower lamp, like the ‘TARDIS’ lamp on the altar to the household gods in The Fires of Pompeii), the battered artefacts and writings. They don't use them just to solve crimes but to build whole cities and empires and worlds. Exploring the real, ancient world turns out to be just as rich, strange and exciting as anything we can imagine in a story.

© Simon Guerrier, 2010

Primary sources

Battlestar Gallactica (1978-9, 2004-)

Doctor Who

- The Romans (1964) – BBC DVD 2698

- The Myth Makers (1965) – soundtrack available from BBC Audio

- The Daleks' Masterplan (1965-66) – episode 10 available on Lost in Time, BBC DVD 1353

- The Tomb of the Cybermen (1967) – BBC DVD 1032

- The Mind Robber (1968) – BBC DVD 1358

- The Time Monster (1972), included in Myths and Legends, BBC DVD 2851

- The Pyramids of Mars (1975) – BBC DVD 1350

- Battlefield (1989) – BBC DVD 2440

- The End of the World (2005) – BBC DVD 1755

- The Fires of Pompeii (2008) – BBC DVD 2605

Lost (2004-10)

The Mummy (1959)

The Mummy (1999)

Rowling, JK, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (1997)

Powers, Tim, The Anubis Gates (1983)

Pratchett, Terry, Pyramids (1989)

Primeval (2007-)

Stargate (1994, 1997-)

Wells, HG, The Time Machine (1895)

Wells, HG, The War of the Worlds (1898)

Wolfe, Gene, Soldier of Sidion (2006)

Secondary sources

Burdge, Anthony, Burke, Jessica, and Larsen, Kristine (eds.), The Mythological Dimensions of Doctor Who (2010)

Campbell, Joseph, The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949)

Dowden, Ken, The Uses of Greek Mythology (1992)

Petrie, WM Flinders, Methods and Aims in Archaeology, (1904)

Thanks to Scott Andrews, Debbie Challis, John J Johnston and Stephen Quirke.

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Books finished, September 2010

A better result than last month. I read The Number Mysteries by Marcus du Sautoy in preparation for an interview for a job I then didn't get (I also had to give a presentation with a mathematics theme and chose the Monument in London). It's a lively, approachable introduction to lots of big ideas, most of which I kept up with.

It covers five main topics: prime numbers; shapes; probabilities; encryption; and how we can use maths to predict the future. There are exercises to do along the way, and more activities on the website. There are QR codes all the way through the book, too, offering additional insights should you be reading with your phone. Du Sautoy ably delivers his lessons to readers of all ages and abilities - and the back cover quotes come from Richard Dawkins and an eight year-old.

It's an engaging and informative book, and proved useful for both my interview and the Astronomy GCSE I've just started. How brilliant to understand how prime numbers might helped cicadas evolve defenses against predators. But, just as at school, I struggled to maintain interest when the numbers were all in the abstract. It's the application of the numbers to solving real-world problems that most excites. Interactive content won't in itself help make the thought-experiment stuff any more enticing.

Kraken by China Mieville was a bit of a disappointment after the glorious and award-winning The City and The City. A whopping great specimen of a Kraken in formaldehyde vanishes from the Natural History Museum, and curator Billy Harrow soon finds himself in amid the increasingly weird underground of competing religious groups with vested interested. While Mieville's work has often been so compellingly original, this felt too often like a knock-off Christopher Fowler, and I found the jokes about Star Trek and pop music a bit trite. It's a fun knockabout thriller with some nice ideas and surprises, which any other day would be quite a recommendation.

Adopting a Child is a guide produced by the BAAF and is part of our initial efforts into the Plan B Spawning Project. Have read various other bits and pieces sent by councils and charities, but they don't count as books.

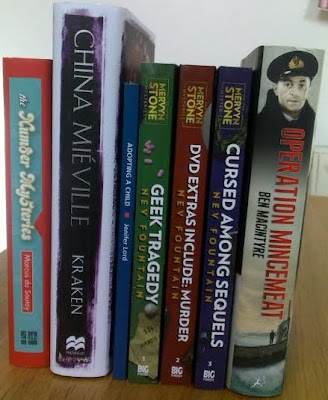

I'm working on the publicity for Nev Fountain's Mervyn Stone Mysteries, so got to read advance copies ahead of hardbacks and leather-bound editions coming out later this month.

And finally, Operation Mincemeat which is a superb bit of work by Ben Macintyre, whose Agent Zigzag I also adored. It's the true story of the man who never was, the dead body planted on a Spanish beach with fake papers in World War Two, to convince the Nazis that the Allies were going to invade somewhere that they weren't.

Macintyre seems to have followed up every possible lead and angle, speaking to the people who were really involved or their families, in the UK and Spain and Germany. He's got a brilliant eye for odd and telling details - there's the man on page 43 who "never wore a hat", or the tradecraft description on page 71 of "wallet litter". The story is fascinating - the plot itself concocted by a bunch of thriller writers - with an extraordinary cast of extraordinary people. A marvel of a book.

Monday, September 27, 2010

The fictional facts of June

26 March 2008

Big cheese Justin Richards asks if I’d write a Slitheen novel. “It'd be set in the past on earth (probably – I'm open to offers!), c50,000 words, Doctor with no companion.”

27 March

I reply with the usual serious, stoic professionalism:

“Ha ha, yes I'd love to. I'd quite like to do something based around the Acropolis in Athens - going back to Ancient Greece but also somehow incorporating the night in 1687 when the Turks blew the place up.

According to Bronowski's "The Ascent of Man", the Greeks what built the Acropolis were at about the same level of sophistication as the Mayans were when the Spanish turned up and wiped them out (they hadn't discovered the load-bearing abilities of arches, for example).

When you say no companion, can I create a one-book one? Maybe a girl from the near future (when the Elgin marbles have been given back to the Athenians)?

Also, woohoo!”

We knock some ideas back and forth, first thinking that the book might start with June visiting the British Museum, then (because that's how The Stone Rose begins) with June on a school trip.

I set to work on a first synopsis, which begins:

“June is 17 and not very confident about her forthcoming A-levels. She’s on a college trip to the Palace of Westminster (not, she has learnt that morning, the “Houses of Parliament”) when she spots the Doctor. He must be important because he doesn’t have a security pass – not even the pastel-coloured stickers that they give to the tourists – and yet the policemen with machine guns let him go where he likes.

June dares to follow him and saves his life when a monster jumps out on him. The Doctor stops the monster by talking nonsense. It feeds on nonsense and illogic – so the Palace is like a restaurant. The Doctor owes June a favour and she asks if he can help with her essay. She’s got to write about the history of democracy.”

She’s called June after my mother-in-law, who has loyally read all my stuff and who likes David Tennant.

Justin has notes on the story itself, and as I work on these over the next week two things occur about June. First, it would help for her to know a bit about Ancient Greece. If I tell the story from her perspective, she can explain the context as we go, rather than relying on lots of exposition from the Doctor. I make her a bit older and a university student, so she’s a bit more of an expert. In fact, I’ll put her on the degree course that my wife and some of our friends did. Then I can pick their brains.

Second, the Doctor’s met all his New Series companions in London so far, so let’s do something different. I could set my prologue in a museum in Manchester (there’s a cast of the Parthenon frieze above the main staircase of Manchester Art Gallery), or I could just cut to the chase…

5 April

Version 2 of the synopsis now begins:

“The Acropolis in Athens, present day. June is 20 and on holiday before her final year at university, where she’s studying Classics. She’s taking notes, ignoring the other, brasher tourists, and trying to work out how she can get this all into her dissertation.

And then she spots the TARDIS materialising down on the road to the theatre. A skinny man emerges… and is promptly set upon by some monsters. No one else notices so June hurries down to investigate.”

16 April

Justin is happy with the synopsis, and just needs a shorter, two-page version for sending to Cardiff for approval.

23 April

Cardiff approves the outline – I’ve now got until 1 October to get the thing written. And a Primeval novel to write at the same time.

I’ve been making notes and reading up on the history. Ken Dowden’s The Uses of Greek Mythology has got me thinking how the events of this story will be retold after the Doctor has gone, so I’m reading Louise Schofield’s The Myceneans looking for stuff I can provide an origin for: bull-leaping, the worship of bulls generally, Deukalion, an image on p.104 of a warrior woman (possibly Athena) in a boars’ tusk helmet and holding a baby griffin...

And I’ve an idea how to tie June into that. One bit of scribble in my notebook reads:

“June's dad is more English than the English, though he was born in Uganda + had to leave when Amin expelled the Indians. These identities are complex. And, of course, the statue of June (i.e. Athena) at the Acropolis has her as a white girl.”

19 May

I visit the set of Primeval as research for that book. Get to meet Laila Rouass who's playing new regular character Dr Sarah Page – an archaeologist working in the British Museum. It looks like the new series of Primeval will air in February 2009, a good two months before my Slitheen book comes out. So if I stick to my plans for June it'll look like I'm copying. Or, since I'm writing both books at the same time, there's more chance I'll get confused.

It’s not that I’m planning to #racefail and make her someone else. It’s more how I’ll portray her. I’m telling my story from June’s perspective anyway, so let’s see her character from her thoughts and actions and not what she looks like.

Think now I could have done that by giving her a surname that suggested her heritage, as we tried to do with Emily Chaudhry. (Though note plenty of companions don’t have surnames: Vicki, Polly, Leela, Adric, Nyssa and Ace.) I shall leave that to the fanfic.

8 June

June is visiting Athens with some other backpackers, ones who don't share her enthusiasm. Extract from my notebook:

“Unreliable history; Chinese whispers etc. & at start June cross cause has read her friend's diary, and it paints June as naïve + wowed by it all. And bored, just wants pizza and beer. And June sees the tourists, only stopping to take photos, not LOOKING, THINKING, IMAGINING”

5 July

I watch Journey's End and the Doctor’s left travelling on his own and all gloomy. It makes more sense for June to be travelling on her own, too, escaping stuff back at home.

10 September

I’m still trying to seed clues about June’s heritage into the book, but they all feel clunky and awkward. From the first draft of chapter one:

“'You're not from round here, are you?'

June's eyes narrowed. 'I'm English,' she told him.

'Oh yes,' said the Doctor. 'From somewhere round Winchester if I'm not mist judging by the accent. But you've spent some time recently in Birmingham + you like the Aussie soaps.'”

Instead, I decide I’m not going to tell you what she looks like at all. We know what sort of person she is from the things she thinks, says and does. We know what drives her – there’s plenty of stuff about what Greece means to her and why she’s out here alone. We see how her perspectives are changed by being with the Doctor. But otherwise the wheeze is she’s an everywoman, looking however the reader wants. In fact, I’m hoping she might even be the reader.

I take solace in this when the angrier end of the internet declares she’s “dull” or “generic”. (Though my favourite comment so far is from someone who’s cross I’ve got “basic fictional facts wrong”.)

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Pornography in hospitals

"Fascinating article, thank you. We finished our final course of IVF earlier this year with no good result and are now looking into adoption. We found the whole process of IVF utterly harrowing: I blogged about it at http://0tralala.blogspot.com/2010/02/ivf.html and then again at http://0tralala.blogspot.com/2010/04/game-over.html.

We were caught between three health authorities so I've used the wanking rooms in four different hospitals in the last few years.

They all provide instructions. For the initial tests into infertility, you're meant to abstain from sex for three days prior to producing a specimen. When it gets to the IVF itself the instructions are more complex – you have to ejaculate as near to 48 hours before as possible, and then on the day itself, once the eggs have been prepared, everyone's just down the corridor waiting on you. So no pressure.

But otherwise the hospitals do very different things. Hospital #1 had a photocopied sheet (which I kept because I thought no one would believe me) that explains things like, “The specimen must be obtained by masturbation...”. It also says, in bold, “NB There are no facilities for the specimen to be produced at [Hospital #1]” and that specimens must be delivered within 45 minutes.

This is something of a bother if you live 45 minutes away from the hospital by car, and worse if you don't have a car. At exactly what stage in the process do you ring for the taxi – before or after?

The taxi driver will inevitably arrive earlier than you're expecting, and then – as you sit red-faced and guilty in the cab – will not know where the hospital is. So you get out the photocopied sheet for the address, and realise as you show it to him that it says in big letters “Semen samples for infertility investigation”.

There is not a lot of dignity in this process.

I've sadly not been able to find the photocopied sheet from Hospital #2, but I'm pretty sure I kept it because it said something along the lines of, “Please do not produce specimens in the waiting room.” I assume they need to tell us this based on past experience.

At Hospital #3 there's a special toilet cubicle with its own key and a small offering of tatty pornography. You collect the key from the nice lady at reception, who provides you with a pot and a brown envelope. You produce your specimen, fill in the label on the jar and hide the jar in the envelope. You then take it back to reception, but don't hand it to the receptionist. Instead, you put it in one of the lockers opposite, lock the door and hand the key to the locker and the key to the wanking room to the receptionist. That way, of course, she won't know what you've just done.

If someone else is waiting for the room, you don't hand the key to them. Instead, you pass it to the receptionist who leaves a beat before handing it the next wanker. You shuffle off, trying not to make eye contact.

Worse is when the next person is already waiting before you go in. You find yourself wondering if you've been to quick or slow. Is there a study on the optimum time spent having a wank?

Because of building work at Hospital #3, our last go at IVF was split between there and at Hospital #4, with me dashing across town in a taxi to deliver freshly harvested bits of my wife. Hospital #4 is an altogether different operation, with a very smart room for a better class of wank. There's a light outside the door to let other people know its occupied, a DVD player as well as the magazines, and a comfy leather chair. Well, I say “comfy” - it would be in any other circumstance. You try not to wonder if the seat is warm from the last occupant, and not to make the chair squeak.

Instead of a locker system, you put your labelled jar into a pneumatic tube. It's like a wank from the future.

The porn was still just as cheap and tatty as that in Hospital #3 – which I'm sure will come as some comfort to taxpayers and think-tanks. And it's a stressy, pressured thing to have to do anyway, and so spectacularly unerotic. As a bloke, this is your one contribution to a process that is, for your partner, awful and intrusive and bruising - physically and mentally. You spend most of your time as a useless spare part, while the person you love goes through hell.

You get used to the matter-of-fact and brutal language with which your plumbing and parts are discussed. You get used to the numbers these tests produce, and the stark probabilities of success. You and your partner are utterly objectified, cuts of meat on the slab.

I appreciate the objections to porn, and in the context a workplace. But as my blog post says, there's a lot of weird reactions to IVF, and the way some people judge you for it – or seem to – is particularly cruel.

IVF is a desperate and terrible thing to go through. I'd have stabbed myself in the eye if the doctors had said it increased the chances of success. £20 a year on some tatty jazz mags doesn't seem very excessive."

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Forthcoming events

Here are two things I'm up to:

Astrobiology at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

Thursday 14 October, 18:30-21:00

The range of talks, screenings and activities include "Good monster/bad monster – scientists and writers discuss what makes a believable alien lifeform. With Simon Guerrier and Dr Zita Martins." (Part of Sci-Fi London)

Sci-fi Egypt at Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

Saturday 23 October, 19:00-21:00

Time travel back to Ancient Egypt to see monsters and aliens pitted against the Egyptian Gods. From the Daleks, who visited the building of the Pyramids, to the Stargates which reach across space and time, the history of Egypt has been a rich source for science-fiction. Grab a free trail, written by Doctor Who books author Simon Guerrier, on Egypt's use in sci-fi and explore the Petrie Museum with a glass of wine! (Part of the Bloomsbury Festival)

Saturday, September 11, 2010

"There are more wild horses in Australia than any other country."

Wednesday, September 08, 2010

"Where they burn books..."

"We pass through Bebelplatz, the square where the Nazis burnt 25,000 books.

The well-read Dr quotes Heine’s remark that,“where they burn books they will also, in the end, burn people,”and wonders whether the burning of the Satanic Verses all those years ago was the first symptom of more recent religious tensions. I start to answer that burning books is easier than burning people, but that’s not actually true.

The destruction of books is the destruction of social structure. The law is in books, as is religion and science and history. To burn a book is a refusal to empathise, to think, to engage. When you have burned down people’s ideas and opinions there is nothing left to stop you burning the people down, too.

Bebelplatz is an empty, open space amid the university, and though there are a couple of artworks about books in general, I think there should be something more lasting. They should have something like the stalls of mixed second-hand reading outside the National Film Theatre, with all kinds of well-thumbed, unsuitable ideas at tantalisingly affordable prices."

Monday, September 06, 2010

Monument to certainty

This is the Monument, built between 1671 and 1677 to commemorate the Great Fire of London.

Climb the 311 steps to the viewing platform – as I did on Tuesday – and as well as the nice views you get a certificate. But the Monument is more than just a memorial to the fire. It was built by Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke – members of the Royal Society.

This is Hooke in a modern painting by Rita Greer. He deduced the wave theory of light and the law of elasticity – which is named after him. He was a pioneer of surveying and map-making. He wasn't a little guy in science. But it was to Hooke that Isaac Newton wrote his famous remark, “If I have seen further [than others] it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants”.

It's a back-handed compliment: Hooke had come close to deducing – before Newton – that gravity follows an inverse square law and that this explains the movement of the planets. Newton developed Hooke's ideas but – Hooke felt – didn't credit him sufficiently. So perhaps Newton's remark is rubbing Hooke's nose in it: the “giant” Newton was standing on had a stoop and may have been a hunchback.

The remark though, is often seen as a testament to scientific endeavour – scientists and mathematicians building on the work of their peers and predecessors. That's why it's engraved on £2 coins (though perhaps that's not the best example of engineering prowess - the coin also shows a a series of cogs in a circle, but there's an odd number so the machinery would not be able to turn as it would pull against itself). As Jacob Bronowski said in The Ascent of Man,

“Year by year, we devise more precise instruments with which to observe nature with more fineness.”Jacob Bronowski, The Ascent of Man (1973), p. 356.

This is Hooke's drawing of a flea from Micrographia, published in 1665. It was the Royal Society's first major book – and the first scientific bestseller.

Micrographia isn't just about looking at tiny things through a microscope. It includes drawings of distant objects, such as the Moon and the star cluster Pleiades (see below). Large and small, these observations changed our view of the universe and our place in it. Theories on gravity needed more and better data about the stars – that meant better telescopes.

In principle, the mathematics of improving a telescope are simple. A lens defracts the light so when you look through it things seem bigger. Look through two lenses at once and they're bigger still. The easiest way to do that is to place a lens at either end of a tube. Increase the distance between the two lenses and you increase the magnification. So to really study the stars, Hooke needed a really long tube...

The Monument was built as a zenith telescope – one that looks straight up. By looking at a fixed star, Hooke hoped to gain evidence that the Earth moved round the Sun. Maths provided the theory: now Hooke would prove it for certain.

The spiral staircase inside means there's a clear view all the way up to the top of the Monument, where a trapdoor would open to reveal the sky. To make the telescope even longer, Hooke worked down in the small cellar – you can see it through the grill in the floor as you begin your climb.

Sadly, though, the telescope didn't work. The vibration from London's traffic meant the readings were never accurate enough. The mathematics of lenses is simple, but the reality is more complicated.

The Monument was used for other experiments. The steps were designed to be used in pressure studies, and are all exactly six inches high.

Hooke continued to study the stars. He worked on the design of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, the first purpose-built research facility in the country. And the more we've discovered since Hooke about space and the position of the stars, the more we come back to the problems that vexed him.

This is me at the 76-metre Lovell radio telescope at Jodrell Bank. It's the third-largest steerable radio telescope in the world. But, like the Monument, size isn't everything. Just beside it is a 38-metre Mark II dish which turned out to be much more accurate and better at listening to higher frequencies.

There's also the accuracy of the observations we make. “Astronomical instruments have been improved,” says Jacob Bronowski.

“We look at the position of a star as it was determined then and now, and it seems to us that we are closer and closer to finding it precisely.

“But when we actually compare our individual observations today, we are astonished and chagrined to find them as scattered within themselves as ever. We had hoped that the human errors would disappear ... but it turns out that the errors cannot be taken out of the observations. And that is true of stars, of atoms, or just ... hearing the report of somebody's speech.”Ibid., p. 358.

Bronowski called this,

“the crucial paradox of knowledge ... we seem to be running after a goal which lurches away from us to infinity.”Since Newton, we tend to assume that the laws of nature are regular, simple and mathematical, and that any deviation from that regularity in our measurements is likely to be our own error. Mathematics can help clarify our observations.Ibid., p. 356.

“When an observer looks at a star, he knows there is a multitude of causes for error. So he takes several readings, and he hopes, naturally, that the best estimate of the star's position is the average – the centre of the scatter.”Ibid., p. 358.

Johann Gauss (1777 to 1855), sometimes known as the “Prince of Mathematicians”,

“pushed on to ask what the scatter of the errors tells us. He devised the Gaussian curve in which the scatter is summarised by the deviation, the spread, of the curve. And from this came a far-reaching idea: the scatter marks an area of uncertainty.

We are not sure that the true position is the centre. All we can say is that it lies in the area of uncertainty, and that the area is calculable from the observed scatter of the individual observations.”Ibid.

The folly of the Monument is not that it didn't work as a telescope but that Hooke, looking up through it from his cellar, was looking for certainty, for proof of the mathematical theory. It's not that maths or physics are uncertain, but measurement is. Bronowski described measurement as "personal". Maths doesn't prove with certainty, but it can show the extent of what we don't know.

(Thanks to Simon Belcher, Danny Kodicek and Marek Kukula who looked this over, and Marcus du Sautoy who pointed out the cogs on £2 coins.)

Friday, September 03, 2010

Books finished, August 2010

Ah. Have been a bit busy on other things - research and job hunting and a new on-spec novel which is currently called "The Dream". But am almost at the end of two books now, so September might be bumper crop.

In other news, the cast for my mini-series Graceless has been announced, and I really couldn't be happier.

Saturday, August 28, 2010

"Give me a Viking funeral"

The Sagas of the Icelanders is a 780-page brick of a book, a selection of the best sagas from the newly translated and spangly complete collection. It's a lovely edition, printed on thick paper cut like crinkly chips.

The Sagas of the Icelanders is a 780-page brick of a book, a selection of the best sagas from the newly translated and spangly complete collection. It's a lovely edition, printed on thick paper cut like crinkly chips.The sagas are fascinating, a collection of histories and adventures about the earliest settlers of Iceland, from about 800 to 1100 AD, and written down a couple of hundred years later (so roughly contemporary with Chaucer). They're a rich and vivid window onto the culture I'd previously read about in my chum Jonathan Clements' Brief History of the Vikings.

The sagas tell of the lives of particularly noteworthy individuals and their families. They explain why different families left Norway and Denmark, how places in Iceland were named and how the land was divided up and fought over. Characters appear in more than one saga, so the stories build up a rich and cross-referenced history packed with detail.

As the Vikings trade with, explore and raid other countries, we get glimpses of Denmark, England, Finland, Ireland, North America, Norway and Scotland – and their kings – as well as meeting characters from Rome and Russia. There are all sorts of morsels to be gleaned from this, such as on language:

"King Ethelred, the song of Edgar, was ruling England at that time. He was a good ruler, and was spending that winter in London. In those days, the language in England was the same as that spoken in Norway and Denmark, but there was a change of language when William the Bastard conquered England. Since William was of French descent [though, er, also a Norman or Norseman], the French language was used in England from then on.”Or there's the insights into contemporary fashion, for example the kjafal, worn in Scotland by both men and women:Katrina C Attwood (trans.), 'The Saga of Gunnlaug Serpent-Tongue' in The Sagas of the Icelanders, p. 572.

"which had a hood at the top but no arms, and was opens at the sides and fastened between the legs with a button and loop; they wore nothing else.”We also learn about romance. There are plenty of loving relationships and a fair few nagging wives. And then there's this telling detail about a lover who knows her business:Keneva Kunz (trans.), 'Eirik the Red's Saga', in ibid., p. 667.

“She welcomed him warmly and offered to search his hair for lice.”While the sagas spare none of the explicit details when it comes to violence, they're coy about the rude stuff. Gisli falls out with his wife, whose gossiping can only lead to trouble. He's so appalled by her, he won't let her in his bed. But she's not taking no for an answer as she climbs in beside him:Keneva Kunz (trans), 'The Saga of the People of Laxarddal',p. 342.

"She soon made clear what she wanted to do, and they had not been lying together for too long before they made up as if nothing had happened.”Generally the sagas tell us two things: what people were like and what they fought over.Martin S Regal (trans), 'Gisli Sursson's Saga', p. 511.

Egil Skallagrimsson, star of his own saga and a cameo in several others, is tall, bald and generally bad news. He continually causes trouble, saying the wrong thing or killing the wrong people, leaving his mates to sort out the mess. On no account should Egil ever be allowed near booze.

"Egil ... stood up and walked across the floor to where Armod was sitting, seized him by the shoulders and thrust him up against a wall-post. Then Egil spewed a torrent of vomit that gushed all over Armod's face, filling his eyes and nostrils and mouth and pouring down his beard and chest. Armod was close to choking, and when he managed to let out his breath, a jet of vomit gushed out with it. All Armod's men who were there said that Egil had done a base and despicable deed by not going outside when he needed to vomit, but had made a spectacle of himself in the drinking-room instead.A page later, for no other reason than to add injury to insult, Egil kills Armod. But that's apparently okay because a) Egil is a big guy who's good at fighting and b) he has a line in sarcastic poetry. The saga continues in broadly the same vein until, in his 80s, Egil manages to start one last scrap before he dies.

Egil said, 'Don't blame me for following the master of the house's example. He's spewing his guts up just as much as I am.'

Then Egil went over to his place, sat down and asked for a drink.”Bernard Scudder (trans) 'Egil's Saga' in ibid., p.139.

There are plenty of other mischievous, selfish and unlikely characters. 'The Saga of the People of Laxardal' is full of strong women, but it's Freydis in 'Eirek the Red's Saga' that most strikes a chord. She's pregnant when some Native Americans / Injuns attack, but berates the other Vikings for running off. Then she spots a dead man:

"His sword lay beside him, and this she snatched up and prepared to defend herself with it, as the natives approached her. Freeing one of her breasts from her shift, she smacked the sword with it. This frightened the natives, who turned and ran back to their boats and rowed away.”These are savage and pagan times, full of dark magic and dreams that predict the future. That said, the Vikings don't behave any different after they convert to Christianity. In fact, they are made to convert with nothing short of brute force:Keneva Kunz (trans), 'Eirek the Red's Saga' in ibid., p. 671.

"King Olaf sent his own royal cleric, a man named Thangbrand, to Iceland ... He preached the Christian faith with both fair words and dire punishments. Thangbrand killed two men who most opposed his teachings.”Christianity seems to co-opt many of the pagan traditions. The Vikings give gifts at winter festivals – men are judged not on what they own but what they give away. Then there are their naming ceremonies:Keneva Kunz (trans), 'The Saga of the People of Laxarddal', p. 352.

"vatni ausinn: Even before the arrival of Christianity, the Scandinavians practised a naming ceremony clearly similar to that involved in the modern-day 'christening'. It is mentioned in eddic poems such as Rigspula (The Chant of Rig), st. 21, and Havamal (The Sayings of the High One), st. 158. The action of sprinkling a child with water and naming it meant that the child was initiated into society. After this ceremony, a child could not be taken out to die of exposure (a common practice in pagan times).”The things these people fight over seem very familiar, too – they might have come from the plots of Charles Dickens. There's various examples of people getting snitty because their neighbours graze animals on their land. There's the fighting over inheritance, there's the perceived slights between families and friends, there's a long whispering campaign against a chap called Thorolf (there are quite a few in the book) by relations of his wife's first husband who feel they're entitled to part of his lands.Glossary, p. 756.

In fact, there's a lot on inheritance – money owed to children, but also the importance of good family and people knowing who your parents are. The implication is that there's virtue in blood. It's something that crops up in 19th Century novels, too. If this belief in the importance of blood has been long-ingrained by culture for 1,000 years, it might explain why it's been so difficult to get past.

Anyway, the chief difference from Dickens is the way these things get dealt with. On a few occasions, one neighbour murders the slaves of another, or sneaks in to the neighbour's house at night to do away with the neighbour. In a particularly grisly example, two 10 year-old children try to fight their fathers' battle and end up killing each other. Murder in Dickens is a Big Plot Thing, here it's an everyday occurrence.

But these things are also long remembered. Sons and grandsons seek revenge for slights visited on dead ancestors. The courts – or allthings – attempt settlements of disputes, but it's an odd process. On page 450, Hrafnkel is prevented from hearing the case made against him by a crowd outside the court. But he's a villain, so that's okay.

Often we're told that someone acted honourably or wisely when all he's done is butcher his enemies or bribed the judges. Honour is a major theme of the stories – and often a catalyst for things going wrong. For all the greed, ambition, sulking and stupidity on display, it's often long-standing oaths that get people in trouble.

The sagas struggle to draw moral lessons from these savage times, and – as with Beowulf – there are odd inconsistencies. Gisli, for example, finds himself ambushed by 12 men who've been wound up by his wife's rumours. He fights bravely:

“Then, when it was least expected, Gisli turned around and ran from the ridge up on the crag known as Einhamer. There, he faced them and defended himself.”But a page later, the odds are too much against him and he dies. The saga adds its own note on his heroism, and despite what we've just been told about him running back to a better position, tells us:Martin S Regal (trans), 'Gisli Sursson's Saga', p. 554.

“They say that he never once retreated.”In short, the sagas are full of rich adventure, vivid characters and telling details. But I can't help feeling they confirm the cliché of the Vikings as brutish, pillaging thugs. As a kid, a description of the Viking way of life struck me as downright cowardly. There's little in the sagas to convince me I was wrong.Ibid., p. 555.

"If the enemy was more powerful than you, you went away. If he could be defeated, you killed, imprisoned or enslaved. You were unswayed by pity or mercy.”Gerry Davis, “Prologue: The Creation of the Cybermen” in Doctor Who and the Cybermen (1974), p. 3.