We had a great day at two neighbouring exhibitions on the gosh-wowness of space. First,

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age at the Science Museum (until 13 March 2016).

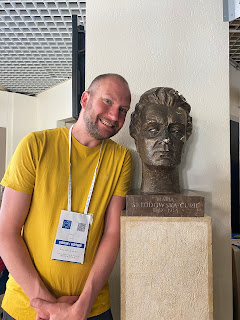

The show begins with

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the visionary physicist who was testing rockets a full decade before the Wright brothers achieved the first manned flight. A huge, hand-made ear trumpet gives a vivid sense of the man, whose deafness stemmed from scarlet fever as a child. That he survived such hardship by being both tough and resourceful is also what makes him the founding figure of the space age.

Sketches from his notebooks show Tsiolkovsky's perceptive sense of what the future in space would be like - with fun drawings of ordinary life while weightless, and of a cosmonaut rushing to rescue a comrade whose lifeline has snapped. Yet facing this is a model of a rocket based on another Tsiolkovsky design, one level naively fitted with baths.

What follows is in the same vein: the incredible vision and ambition, tempered by the tricky, counter-intuitive practicality of getting into and surviving in space.

The exhibition covers the politics behind the Soviet space programme - for example, lead rocket engineer

Sergei Korolov had spent years in the gulag. But I'm glad I'd recently read

Nick Abadzis's Laika (2007), an extraordinary, gripping, harrowing account of the first dog in space and the humans responsible for her, which gave a more rounded account of Korolov and the pressures under which he and other Soviets existed.

In fairness, an exhibition panel on

Yuri Gagarin, who in 1961 became the first person in space, underlines the politics:

“In the end, the decision to select Gagarin as the first cosmonaut was highly symbolic and political, and his working-class upbringing and photogenic smile were just as important as his ability to withstand the extreme conditions of space flight.”

Last year,

I wrote a piece about a Communist pamphlet signed by Gagarin in the possession of Croydon Airport Society. Gagarin's success was a propaganda coup - the exhibition shows him touring the UK, meeting Harold Macmillan and factory workers, and shows off the signed photograph of the royal family he received after he dined with them. But the pamphlet, with its cover illustration showing a black-and-white Gagarin looking down on a pale blue Earth, underlines a missed opportunity: the Soviets had not thought it necessary to provide Gagarin's capsule with a camera.

That error was quickly realised, and the exhibition includes the Konvas cine camera used by second cosmonaut Gherman Titov, the first person to photograph and film the Earth from space. There's also a blurry, black and white image that he took on 6 August 1961.

Another PR coup is spelt out on the panels beside the spacesuit and capsule of

Valentina Tereshkova, who on 16 June 1963 became the first woman in space. If that was not enough, her spaceflight lasted just less than three days,

“longer than all the preceding American manned space flights combined”.

But despite these propaganda successes, the Americans were fast catching up - and the exhibition suggests that this pressure on the Soviets to stay ahead meant they pushed too far, resulting in a series of accidents and failures, and them falling behind in the race to the Moon.

Having made that point, the exhibition then quite takes your breath away by presenting the

Soviet LK lander from the never-attempted manned mission to the Moon. Its striking how similar much of it is to the American version - though we wondered how much that was down to both programmes being faced with the same set of problems, or whether there'd been some copying. But the differences are compelling, too, such as the spherical rather than boxy module, and the flourish of the curling handholds.

A lot of the American space programme's rockets and spacesuits are in dazzling white, so a spacecraft in bare, grey metal seems almost naked. I wondered if that also meant cosmonauts were exposed to more extreme temperatures and conditions than astronauts. We learned later that at one point in the programme the Soviets saved space inside their capsules by putting cosmonauts not in spacesuits but in ordinary clothes - a much more hazardous way of doing things.

There's lots to admire in the simple, user-friendly designs of a lot of the Soviet spacecraft. I particularly like the control boxes including a globe of the Earth that rotated in keeping with a capsule's relative position. But I'm a bit glad to be too tall to fit any of the tiny, tight boxes on display, cosmonauts squished up small for hours on end. If we were still under any illusion of space travel being glamorous, a panel tells us that

Helen Sharman - first Briton in space - sweated two litres into her endearingly little spacesuit, and had to dry it out afterwards to prevent it going mouldy

It's more than there being a distinct lack of comfort. The exhibition celebrates the

incredible mission in 1985 to save space-station Salyat 7 - but considering the risks involved and the conditions faced by the cosmonauts, I wondered if the US would ever have countenanced trying something similar.

Laika is good at showing individuals subsumed by the Soviet state, their personal feelings discretely put to one side. And perhaps that's characteristic.

Lucy Worsley's Empire of the Tsars showed how little the lives of most Russians counted for, how many died on projects such as building St Petersburg or in fighting horrific wars.

That's the haunting sense I'm left with at the end of the exhibition: that these extraordinary men and women were so readily expendable.

After coffee and cake, we mooched next door to

Otherworlds at the Natural History Museum (until 15 May 2016). Brilliantly curated by

Michael Benson, it's a collection of jaw-dropping images from the Solar System, blown up large and presented in darkness with a soundtrack by Brian Eno.

|

Crescent Jupiter and Ganymede

Mosaic composite, Cassini, 10 Jan 2001 |

A lot of the images present boggling juxtapositions: a close up Moon with a crescent Earth behind it, or a vista of Martian sand dunes that might be waves on an alien sea. A series showing the small black dot of Earth transiting over the fiery disc of the Sun is another good example. There are plenty of unusual angles and perspectives that take a moment to "get".

The trick is that these still images suggest movement on an enormous scale. With perfect simplicity, they show not individual bodies in space but the way they - and little us - are related. After the noise of

Cosmonauts and the crowds in the main parts of both museums, it was utterly captivating - not just to me, but to the rest of the visitors gawping round in wonderstruck hush.

(If you can't make it, there's an

accompanying, eye-popping book.)