"Your maths is correct, but your physics is abominable," said

Albert Einstein (in French) of a 1927 paper by a Catholic priest.

Abbe Georges Lemaitre, from a small university in Belgium, had published

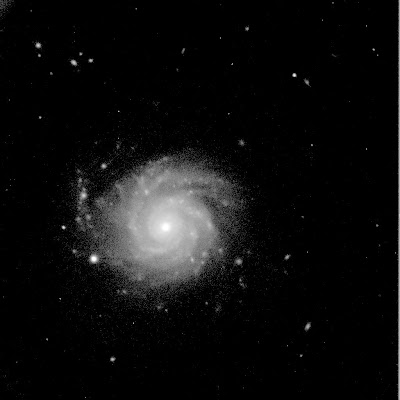

'A homogeneous universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae' in the

Annales de la Societe Scientifique de Bruxelles. Lemaitre - who had previously worked with

Arthur Eddington at Cambridge and then Harlow Shapley at Cambridge, Massachussets - proposed the idea of an expanding universe. At the time, Einstein and physicists generally believed in a "finite, closed and static" universe, a "cosmological constant" - despite the fact that his own theory of relativity suggested otherwise.

But Lemaitre,

"derived the relation for an expanding universe to be between the speed of a galaxy receding from an observer and its distance from the observer. Lemaitre also provided the first observational estimate of the slope of the speed-distance curve that later became known as Hubble's law when the American astronomer Edwin Hubble reported his initial observations on galaxies in 1929. These two important properties of the universe were proposed two years before the measurements that would begin a new era in astrophysical cosmology."

When Hubble published his observations, Lemaitre sent his own paper to Eddington and Einstein quickly confirmed that his theory "fits well into the general theory of relativity". There were still lots of questions to be asked about what

drove the expansion, and several notable physicists were still skeptical (the "Big Bang" was initially a term of contempt for the idea), but Lemaitre has been called "the father of the Big Bang".

And yet, the idea had been proposed 150 years previously. Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove's

Trillion Year Spree refers to a footnote in Erasmus Darwin's 1791 verse discussion,

The Economy of Vegetation.

The footnote explains Darwin's response to William Herschel's own "sublime and curious" ideas about the construction of the heavens. Herschel had discovered 1,000s of star clusters (and the planet Uranus) with his telescope. (You can see

Herschel's 40-foot telescope at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich and visit his

house in Bath.)

According to Darwin, Herschel had observed that there were proportionately fewer stars around the clusters, and concluded that infinite space had first been evenly sprinkled with stars but that, through gravity, they had "coagulated" together. Herschel also observed that the stars were moving round some central axis (that is, that the Milky Galaxy is slowly turning), and concluded that they must "have emerged or been projected from the material, where they were produced."

"It may be objected, that if the stars have been projected from a Chaos by explosions, that they must have returned again into it from the known laws of gravitation; this however, would not happen, if the whole of Chaos, like grains of gunpowder, was exploded at the same time, and dispersed through infinite space at once, or in quick succession, in every possible direction."

I didn't know much about Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) until reading

Trillion Year Spree, whose authors - taking their lead from

Desmond King-Hele's The Essential Writings of Erasmus Darwin (1968) - devote three and a half pages to him. Hele, they say "lists seventy-five subjects in which he was a pioneer".

"Many inventions stand to Erasmus Darwin's credit, such as new types of carriages and coal carts, a speaking machine, a mechanical ferry, rotary pumps, and horizontal windmills. He also seems to have invented - or at least proposed - a rocket motor powered by hydrogen and oxygen. His rough sketch shows the two gases stored in separate compartments and fed into a cylindrical combustion chamber with exit nozzle at one end - a good approximation of the workings of a modern rocket, and formulated long before the ideas of the Russian rocket pioneer Tsiolkovsky were set to paper."

Brian Aldiss with David Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, p. 35.

Darwin's long poems with their awkward rhymes might often seem "daft" to us now (though Aldiss and Wingrove cite some of his deft lines), and his reputation was damaged by parodies in his own time.

"Parodies of his verse in George Canning's Anti-Jacobin, entitled The Loves of the Triangles, mocked Darwin's ideas, laughing at his bold imaginative strokes. That electricity could ever have widespread practical application, that mankind could have evolved from lowly life forms, that the hills could be older than the Bible claimed - those were the sorts of madnesses which set readers of the Anti-Jacobin tittering. Canning recognized the subversive element in Darwin's thought and effectively brought low his reputation."

Ibid., p. 36.

He was also eclipsed by his grandson Charles, though Erasmus's

Zoonomia, published in two volumes in 1794 and 96,

"explains the systems of sexual selection, with emphasis on promiscuity, the search for food, and the need for protection in living things, and how these factors, interweaving with natural habitats, control the diversity of life in all its changing forms."

Ibid., p. 36.

Erasmus acknowledged that these "evolutionary processes need time as well as space" and "emphasizes the the great age of the Earth", contradicting the "then-accepted view" of Bishop Ussher's that the Earth was created in 4004 BC. (Aldiss and Wingrove admit that "the Scot, James Hutton, had declared in 1785, thrillingly, that the geological record revealed 'no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end'.")

Aldiss and Wingrove call Erasmus Darwin "as a part-time science-fiction writer", though I think they rather overplay the case for his,

"prophesysing with remarkable accuracy many features of modern life - gigantic skyscraper cities, piper water, the age of the automobile, overpopulation, and fleets of nuclear submarines".

Ibid., p. 37.

But perhaps Darwin has a part to play in sci-fi. The authors nominate

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein as the first work of science-fiction, a book that Shelley herself claimed to be the result of a nightmare in 1816, following,

"late night conversations with Shelley, Lord Byron and John Polidori, Byron's Doctor. Their talk was of vampires and the supernatural. Polidori supplied the company with some suitable reading material; Byron and Shelley also discussed Darwin, his thought and experiments. At Byron's suggestion, the four of them set about writing a ghost story apiece."

Ibid., p. 53.

I find this all fascinating and have been meaning to write it all up for months. Note to self to investigate Darwin further. I also see you can visit

Erasmus Darwin's House in Staffordshire.