Part one

The blog of writer and producer Simon Guerrier

Good news first. Having blogged yesterday I popped to the shops for a copy of the Times - and was a bit surprised to find that the brother's jaunt occupies all of page 3. And he gets a credit for his precious photos.

Good news first. Having blogged yesterday I popped to the shops for a copy of the Times - and was a bit surprised to find that the brother's jaunt occupies all of page 3. And he gets a credit for his precious photos.

K. had also organised big-screen Doomsday, punters assembled before a projector screen as if it were a new kind of England game. The sound popped and pixellated every now and again, but otherwise we were dumbstruck. Cor, that was a bit bloody good wasn't it? See right for one quarter of the verdict from the Time Team.

K. had also organised big-screen Doomsday, punters assembled before a projector screen as if it were a new kind of England game. The sound popped and pixellated every now and again, but otherwise we were dumbstruck. Cor, that was a bit bloody good wasn't it? See right for one quarter of the verdict from the Time Team.

“I was reading in the paper the other day bout those birds who are trying to split the atom, the nub being that they haven’t the foggiest as to what will happen if they do. It may be all right. On the other hand, it may not be all right. And pretty silly a chap would feel, no doubt, if having split the atom, he suddenly found the house going up in smoke and himself torn limb from limb.”

PG Wodehouse, Right ho, Jeeves, pp. 170-171.

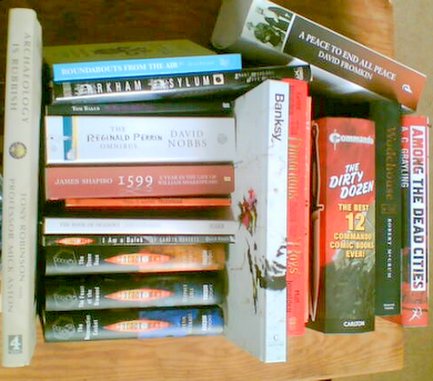

This reminds me of Chaplin’s Great Dictator, in which there’s some silly mucking about in a concentration camp, an astonishingly misjudged laugh. Chaplin later said that he regretted these scenes, and would never have dreamt of doing them had he known what the camps really involved. Though there’s arguments about what people would and should have known at the time, it now plays as woefully crass. Some of my more bookish correspondents complain that I did not include full details of the volumes received on Saturday. Having counted again, I also realise there are 20 of the blighters - and that's not including the collected "Gifted" which my boss Joe sent just because he's so nice.

Some of my more bookish correspondents complain that I did not include full details of the volumes received on Saturday. Having counted again, I also realise there are 20 of the blighters - and that's not including the collected "Gifted" which my boss Joe sent just because he's so nice. So all in all I shall be busy for the next few weeks. Have yet to attempt the making of bread or afixing my shiny new monitor. Been a bit caught up with other pressing bits of work.

So all in all I shall be busy for the next few weeks. Have yet to attempt the making of bread or afixing my shiny new monitor. Been a bit caught up with other pressing bits of work.

“Some people act a memory, the Superintendent thought, noticing his concentration, others have one. In the Superintendent’s book, memory was the better half of intelligence, he prized it highest of all mental accomplishments; and Smiley, he knew, possessed it.”

John le Carre, Smiley’s People, p. 43.

And so my hunt for Karla comes to an end (having previously read Tinker, Tailor and the Honourable Schoolboy).“I have destroyed him with the weapons I abhorred, and they are his.”

Ibid, p. 391.

We’re kept guessing right up to the end about whether it’s going to all work out or implode into some grisly snafu. That uncertainty is helped by knowing that le Carre stories so often end with someone’s sudden and miserable death. A great raft of things I'm producing has been announced: Season 7 of Bernice Summerfield.

A great raft of things I'm producing has been announced: Season 7 of Bernice Summerfield.  Arrived at something ungodly in Caen next morning, woken to classical music which got ever more insistent. With time just to wolf a coffee, we found the car again and rode out on the D84 (also, I explained to my delighted fellow passengers, the name of a nifty robot in Old School Dr Who).

Arrived at something ungodly in Caen next morning, woken to classical music which got ever more insistent. With time just to wolf a coffee, we found the car again and rode out on the D84 (also, I explained to my delighted fellow passengers, the name of a nifty robot in Old School Dr Who). “[Viv’s] nicknames were ‘the spine’ and ‘crime’. I don’t know where the first came from, but the latter predicated on his ability to spend all day in the pub, and always with discretion navigate his turn to buy a drink. ‘Crime doesn’t pay.’ But none of us cared because his company was worth the price. Viv was into literature, Keats and Beaudelaire, and turned me on to both these great poets. Plus the funniest book I’ve ever read, the great A Rebours, is one of the two novels Marwood shoves into his suitcase at the end of the film.”

Bruce Robinson, Introduction to Withnail and I – the screenplay, p. viii.

A Rebours (or, “Against Nature” as it’s published in English) is a hugely self-indulgent French decadent novel first published in 1884. It influenced the fin de siecle of Oscar Wilde, and is referred to in A Picture of Dorian Gray as “the strangest book he had ever read”. It remained something of a cult hit ever after, and was especially cool in the 1960s. The introduction to the Penguin Classics edition cites Marianne Faithfull’s autobiography where she’d ask her dates if they’d read A Rebours.“And if he said yes you’d fuck.”

Marianne Faithfull, Faithfull, p.100, cited in ‘Introduction’ by Patrick McGuinness, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against nature (a rebours), p. xv.

After a life of sex, drugs and rock and roll that eats up too much of his inheritance, the aristocratic Des Esseintes retires to a small house and solitary life of thought and indulgence. We glimpse his put-upon servants, cabbie and doctor, and there are fleeting accounts of his exes and parents, but mostly it’s Des Esseintes’s views on life, subject by subject.“I have a great deal of sympathy with the hon. Lady's comments on seemingly cumbersome words such as “impliedly''. However, lawyers tell me that, over the years, those words acquire a meaning that all lawyers understand in the context of Acts of Parliament and Bills before Parliament. Although she is worried about the cumbersome and alienating nature of the prose, “impliedly'' achieves something in the text. If we did not keep it, we would have to list every possible purpose in the agreements reached with other countries, which would almost certainly result in their being revisited often. Fraud, international or otherwise, evolves and changes over time. As one loophole closes, others may open and other ways of defrauding the system are created. The language we use in our Acts of Parliament seeks to put a stop to such practices and to keep up with that evolution.”

Angela Eagle on the Social Security Fraud Bill [Lords], Official ReportCommons Standing Committee A, 9/4/01.

So, er, international fraud would get away with new tricks if a law said “definition is implied” or that something “implies definition”?“Many different styles can be characterised as Modernist, but they shared certain underlying principles: a rejection of history and applied ornament; a preference for abstraction; and a belief that design and technology could transform society.”

Information board at the V&A's Modernism exhibition, June 2006.

The huge exhibition (until 23 July) makes clear that Modernism emerged as a rejection of terrible things past, advocating a new, post-world-war order. Much of it derives from friendly, leftie ideas about social equality: better housing for the poor, workplaces that ease the burden on the worker. But there’s a great difference between equality and the sort of uniformity these grand designs impose."At age fourteen, by a process of osmosis, of dirty jokes, whispered secrets and filthy ballads, Tristan learned of sex. When he was fifteen he hurt his arm falling from the apple tree outside Mr Thomas Forester's house: more specifically from the apple tree outside Miss Victoria Forester's bedroom window. To Tristan's regret, he had caught no more than a pink and tantalising glimpse of Victoria, who was his sister's age and, without any doubt, the most beautiful girl for a hundred miles around."

Neil Gaiman, Stardust, p. 29.

Knocked through this very quickly and pleasurably, patting myself on the back for noting various references to what Grimm fairy-tales I've read (the Dr got both books for Christmas). Gaiman's got the feel, the strangeness and the Freudian undertones (glimpses of vivid sex and brutality) spot on, though his morality is more fathomable and consistent. Went to the exhibition of Michelangelo’s sketches at the British Museum (until 25 June) which was really rather busy. In between getting shoved and stepped on by the myriad other punters, saw some really fascinating stuff.

Went to the exhibition of Michelangelo’s sketches at the British Museum (until 25 June) which was really rather busy. In between getting shoved and stepped on by the myriad other punters, saw some really fascinating stuff.

“The whole experience of being hit by a bullet is very interesting and I think it is worth describing in detail.”

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, p. 137.

No, this is E. Blair, not T. Had read this while doing my A-levels and took it to Spain to reread. How’s that for diligent?“The human louse somewhat resembles a tiny lobster, and he lives chiefly in your trousers. Short of burning all your clothes there is no known way of getting rid of him. Down the seams of your trousers he lays his glittering white eggs, like tiny grains of rice, which hatch out and breed families of their own at horrible speed. I think the pacifists might find it helpful to illustrate their pamphlets with enlarged photographs of lice. Glory of war, indeed! In war all soldiers are lousy, at least when it is warm enough. The men who fought at Verdun, at Waterloo, at Flodden, at Senlac, at Thermopylae – every one of them had lice crawling over his testicles.”

Ibid., p. 51.

We only rarely get any hint of how the events affect Orwell himself (or his wife – I’d be fascinated to know what she thought about it all). He’s a bit surly and he could do with more cigarettes, that’s about it.“When Helen saw a movie in which the happy ending was that the super-intelligent working-class girl received the letter telling her she’d been accepted for the swanky academy, she always wondered whether that really was a happy ending. The likely outcome of the girl getting her education would be that in the future even if she loved her parents dearly she wouldn’t be able to stop herself being bored and petulant with them and though she struggled against it she wouldn’t be able to resist finding her home town tedious, tiny and peculiar.”

Alexei Sayle, The Weeping Women Hotel, pp. 147-8.

Finished this while on the plane out to Malaga, and as those who replied to my thoughts on Sayle’s Overtaken advised, it’s really rather special."Is all my brain and body need..."Off to Spain 'cos someone who's almost family is getting hitched. And as we hurry ourselves out the door, it strikes me as odd where Dr Who thought'd make a good date with Rose.

"Das ist gut! C'est fantastique!

Hit me! Hit me! Hit me!"