As well as all this, there's a new "Sufficient Data" infographic from me and Ben Morris, this time on the ages and ages of the actors playing Doctor Who.

Thursday, June 23, 2022

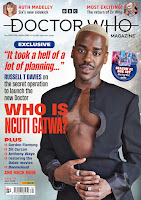

Doctor Who Magazine #579

Wednesday, June 22, 2022

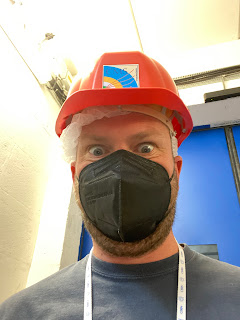

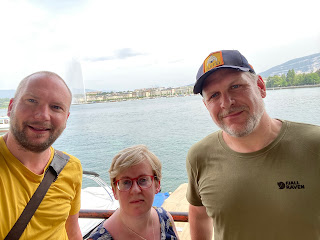

CERN: Science Fiction and the Future of Detection and Imaging

I've had the most amazing few days in Geneva as a guest of Ideas Square at CERN. It's the first time I've been out of the UK in three years, and I was jangly with nerves for a good week before setting off; I'll be jangly with excitement about it all for some time to come.

During lockdown, my friend Dr Una McCormack roped me into some online sessions where sci-fi writers (hello!) were brought in to help / hinder the work being done by students from round the world in attempting to imagine the future impact of technology. This week, a bunch of us assembled in person, got a tour of the Large Hadron Collider and other CERN bits and bobs, and had lots of really interesting chat about, well, everything really. There was high-end physics, and high-end gossip, and high-end physics gossip.

I've returned home with pages and pages of notes in my notebook - bits of new ideas, lists of things to read or look into, random bits of detail. For example, one thing that boggled my brain was that work on constructing the CMS detector (one of a number of detection instruments located round the Large Hadron Collider) was delayed by the discovery of Roman ruins on site which then had to be painstakingly excavated. I'm taken by the Nigel Kneale-ish thought of ancient ghosts being picked up by the sensitive detectors...

Then there was the fact that when building this underground facility the team had to dig through a subterranean river. To do so, they dug down to the level of the river, then froze it and dug through the ice, constructing a concrete-lined shaft through the middle before letting the ice thaw. Ingenious!

And how extraordinary, how liberating, to discover that in visiting the CMS we had crossed the border into France without a moment's thought, let alone all that mucky business with passports. Coming home, there weren't enough ground crew to let us off the plane so we sat stewing for 45 minutes. There must be a better way of doing things, I thought. Which was exactly the sort of thing these few days have been about.

Here are a few pictures...

|

| View of mountains from CERN hostel |

|

| Geneva tram, for my father-in-law |

|

| More mountains, plus v hot writer |

|

| Tour of the CMS facility; photo of detector like a gothic rose window |

|

| Going underground |

|

| Warning signs to give one pause |

|

| The LHC creates a magnetic field; look at its effect on these paperclips! |

|

| Doctor U and her plucky assistant |

|

| New hat / cool museum |

|

| Hot, hot evening, and yet snow on the mountains |

|

| Marie Curie clearly delighted to meet me |

|

| Very heavy lead, so dense it would shatter to dust if dropped |

|

| Arty reconstruction of CMS, using mirrors (cf Maxtible in The Evil of the Daleks) |

|

| Old-skool, pretty wiring in old device |

|

| Where the web, and so much of my life, began |

|

| Cool retro tech in a garden |

|

| More cool, retro tech |

|

| The Champions (ie me, Una McCormack and Matthew De Abaitua) |

Friday, June 17, 2022

Play for Today: The Evolution of Television Drama, by Irene Shubik

The Wednesday Play was a prestigious anthology of (mostly) one-off plays, 182 of them broadcast by the BBC between 1964 and 1970. The series then moved to a different day of the week and, as Play for Today, a further 306 (mostly) one-off plays were broadcast between 1970 and 1984. One of the producers, Irene Shubik published this memoir in 1975 (and produced a revised, updated edition in 2001), detailing how and why plays were put on.

One reason for writing such a book is to have a permanent record of the plays at all. As Shubik says at the end of the book, the most noteworthy episodes were repeated - but usually just once. There was no facility to buy episodes for home viewer or to see them screened anywhere else. In many cases, episodes weren’t kept by the BBC anyway. The British Film Institute, with a remit to collect and preserve key bits of screen culture, lacked the resources to do much.

“All it [the BFI] can do is send its recommended lists to the BBC in the hope that the programmes will not actually have been wiped or junked. Meanwhile, there is no guarantee that a student in a hundred years time, hoping to make a study of English television productions in the 1970s will have sufficient material to do so; most of these ‘chronicles of our times’ will have vanished into the ether, condemned by the sheer weight of their numbers, to oblivion.” (p. 182)

She provides a long list of all the plays broadcast in the series up to 11 December 1972 - a valuable resource in the days before the internet made such things readily available - and then another, shorter version of those plays that she herself oversaw. She divides these plays into chapters based on type or style, and provides us with her insights - how they were commissioned, anecdotes about production, responses they received from the press and public. There's an engaging mix of gossip and technical detail, just the sort of thing I like.

There is a brief history of television drama prior to 1964: BBC Television began in December 1936; in 1937 some 123 plays were broadcast, an “astonishingly high figure” though many “were repeats and most were very short in length, from 10-30 minutes”. The majority were adaptations from stage and prose works,

“But even in 1937 there were two pieces put out which were original commissions for the medium: The Underground Murder Mystery by J Bissell Thomas (lasting ten minutes) and Turn Round by SE Reynolds lasting thirty minutes. These were the first two pieces of original English TV drama.” (p. 33)

Though there continued to be original works in the years that followed, Shubik marks 1953 as a pivotal moment in television drama.

“The reason why certain names keep recurring from that year [1953] Wilson, Kneale, Philip Mackie, John Elliot, and Anthony Stevens, among them, was that a policy had been adopted of putting certain promising writers on the staff, to form a sort of writer’s workshop. The idea was that by adapting and story-editing other people’s scripts, and working close to the productions, this nucleus of writers could best learn about the medium. Hierarchically, the structure of the department was Head of Drama (Michael Barry) and Head of Script Department (Donald Wilson), with a group of writers and directors working on all types of drama (plays, series and serials) under their supervision. … Nigel Kneale was the first writer to be put on this scheme, in 1951 [having] convinced the BBC drama department to give him a contract (at £5 a week), first to adapt one of is own [prose] stories and later (eventually at £15 a week), to become a staff writer and adapter.” (p. 34)

She remarks on how little this was.

The next pivotal moment in her history is the ITV network ABC (covering the Midlands) making Canadian producer Sydney Newman its head of drama in 1958. Two years later, Newman gave Shubik a job as script editor. In 1963, he began as Head of Drama at the BBC and gave Shubik a job there the following year.

There is a lot of Newman’s character, behaviour and appearance. Shubik quotes fellow story editor Peter Luke’s assessment of Newman as “a cross between Genghis Khan and a pussycat”, refers to his “Groucho-Marx-like sense of humour” and thinks him “undoubtedly one of the most dynamic men who ever worked in English television.” (p. 9). She’s good on why Newman had such an impact, too.

For example, “probably the first controversial piece”, or play, broadcast in the UK under Sydney Newman was Ray Rigby's Boy With a Meat Axe. Shubik quotes from the review by Norman Hare in News Chronicle on 22 November 1958: the play “included a murder accusation, a young girl getting drunk, and a street fight … as well as using a lavatory as one of the settings” (p. 25).

Newman wanted contemporary, revenant drama, yet for all his dramatists tackled the issues of the day, Shubik says Newman also “wanted as much variety as possible on the programme and a few plays starring ‘blondes with big boobs’ to temper the gloom” (p. 19). And while ABC drama anthology series Armchair Theatre did well,

“The size of the audience, as Sydney was always modestly reminding us at script meetings, was undoubtedly helped greatly by the fact that the programme followed [variety show] Sunday Night at the London Palladium” (p. 31)

Given this last point, it’s odd that when Shubik devotes a chapter to audience response, she doesn’t think there’s much to be gained from comparisons across genre. This is her on the merits of knowing numbers of viewers and their percentage score for a given programme (the “appreciation index”):

“Within the framework of his own programme, therefore, the producer can get some idea from programme research as to which plays were most watched and most liked; to compare one’s own programme with other types of programmes, for example comedy or documentary or sport, is a useless occupation as it is accepted that audiences for different types of viewing will differ.” (p. 180)

Newman recognised that this simply wasn’t true: a significant number of those watching a variety show would stay on to watch contemporary drama, even if only because they didn’t make the effort to switch off or over. Likewise, when Newman devised Doctor Who, he wanted a new, made-for-television drama that would retain the audience from sports show Grandstand and appeal to those tuning in for pop music show Juke Box Jury. Achieving this not only made Doctor Who a hit but led to the BBC dominating Saturday evening TV.

There’s no mention of Doctor Who here. Sadly, Shubik tells us that her oversight of anthology series Out of the Unknown (sci-fi) and Thirteen Against Fate (adaptations of stories by Georges Simenon) are not within the purview of this book - a shame, as it would be interested to know how she thought her work on these differed to the more prestigious one-off plays. She briefly mentions her time as story editor on Story Parade, and one episode in particular: an adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel (about a detective who is a robot), but doesn’t mention Terry Nation, who adapted it for TV.

What is useful for my research into Doctor Who story editor David Whitaker is the many insights into Sydney Newman: why he broke up the BBC’s drama department (to increase productivity, p. 32); what made him a good producer (“the ability to assess personalities and match talents successfully”, p. 26); what he thought made a good story or script editor (“the courage to tell the author it [a script] was not good enough”, p. 29); what he’d look for when viewing a “producer’s run” of a play in the rehearsal room ( he had a “keen instinct for what was dramatic in a production and what was boring and self-indulgent on the part of the director or actors” and Shubik learned, from him, to “look at an outside rehearsal not as a stage play, but through the eyes of the cameras”, p. 49).

There are other interesting details too - why filming is more expensive than recording on videotape, the practicalities of working with different writers, the buzz of production with limited budget and time. Plus I have another production to add to my list of TV and film made at Grim’s Dyke: an episode of The Wednesday Play by David Rudkin, House of Character, including filming at “Grims Dyke Manor [sic] and Ham House in thick fog” (p. 91), with production beginning in October 1967.

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

Doctor Who Chronicles: 1967

In "From the Archives", I trawl through BBC paperwork to reveal "the story of a turbulent year and last-minute changes in the making of Doctor Who."

In "Life on Mars", I examine the life of writer Brian Hayles, whose "most enduring contribution to Doctor Who was the creation of the Ice Warriors, but this was just part of his prolific output."

If this is your sort of thing - and why in heaven wouldn't it be? - you can still buy my book on the 1967 Doctor Who story The Evil of the Daleks. And there's also the issue of Doctor Who Chronicles for 1965, in which I wrote some stuff.

Sunday, June 12, 2022

Into the Unknown: the Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale, by Andy Murray

Andy Murray is really good at identifying what makes so much of Kneale's work highly effective. One sentence, from Kneale himself on why the 1979 version of Quatermass didn't match the power of the earlier serials, is telling of his work as a whole:

"The central idea was too ordinary." (p. 210)

Also excellent is teasing out common themes, interests, strengths. I'd always found it odd that the author of Quatermass and Nineteen Eighty-Four wrote sitcom and for Sharpe and Kavanagh QC. Now I see how these things all connect: Murray's especially good on demonstrating how the Kavanagh episode, about an old and respected doctor who might by a former Nazi, is thematically in keeping with Quatermass and the Pit, in which ancient and long buried evil is suddenly brought into the light.

There's a good sense of Kneale in all this - or rather of two Kneales. One is Nigel, the cantankerous, curmudgeonly writer, all too ready to say what he thinks about other people's failings and continually cross about money. The other is Tom: kindly, supportive and practical, a devoted husband and father - and model for the dad in the Mog books.* My sense is that many of the people Murray spoke to either met one or other of these men. There was something mercurial about Kneale; something fittingly impish.

Among the many fascinating details, I was struck that, though Kneale left his staff-writing job at the BBC to go freelance from 1 January 1957, he continued to make use of his office at the BBC - presumably in or around Lime Grove - which was convenient for meeting up with directors etc. His wife, Judith Kerr, continued to work in the BBC's script unit until the end of 1957 - her six-part adaptation of Buchan's The Huntingtower was broadcast in June and July (Murray says the Scottish dialogue polished by head of department Donald Wilson (p. 88)); another adaptation by Kerr, The Trial of Mary LaFarge, was broadcast on 15 December. Kerr left the BBC around this time as her daughter was born the following month.

That means she must have overlapped with David Whitaker, whose life I'm currently researching. He joined the unit around October 1957, his first work as a staff writer - for which he didn't get a credit on screen or in Radio Times - broadcast less that two weeks after Kerr's last. I'm rather taken by the potential of that overlap, given that Whitaker later asked Kneale to write for Doctor Who.

This has sparked some further thoughts - but more on that anon.

* How amazing to learn (p. 145) that the dad in The Tiger Who Came to Tea was in part modelled on Alfred Burke, at the time the star of detective series Public Eye, and a neighbour of Kneale and Kerr.

Wednesday, June 08, 2022

Competition, by Asa Briggs

Very quickly after launching in September 1955, ITV offered more hours of entertainment than the BBC. Advertising revenue also quickly made ITV very profitable - a one-shilling share in 1955 was worth £11 by 1958 (p. 11). With more money on offer, there was a huge flow of talent from the BBC; 500 out of 200 staff members moved to ITV in the first six months of 1956. The result was a desperate need for new people and a sharp rise in fees, doubling the cost of making an hour’s television (p. 18). Audiences responded to the fun, less formal ITV. The low point for the BBC came in the last quarter of 1957,

“when ITV, on the BBC’s own calculations, achieved a 72 per cent share of the viewing public wherever there was a choice.” (p. 20)

A lot of what follows is about the BBC’s concerted efforts to claw back that audience. But the book is as much about rivalry inside the BBC - the infighting of different departments, the effort to make the new BBC-2 different from and yet complementary to BBC-1, and the ascendance of TV over radio.

The latter happens gradually but with telling shifts. Since 1932, the monarch had addressed the nation each Christmas by radio; in 1957, Queen Elizabeth made the first such broadcast on TV (p. 144). That seems exactly on the cusp of the audience making the switch: in 1957 more radio-only licences were issued than radio-and-TV licences (7,558,843 to 6,966,256); in 1958 there were more TV-and-radio than radio-only licenses (8,090,003 to 6,556,347) (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). There’s a corresponding flip in the money spent on the two media: in 1957-8, expenditure on radio was more than on TV (£11,856,120 to £11,149,207); in 1958-9, more was spent on TV than radio (£13,988,812 to £11,441,818), and that gap only continued to widen (source: Appendix C, p. 1007). Yet aspects of BBC culture were slower to shift: Briggs notes that “The Governors … held most of their fortnightly meetings at Broadcasting House [home of radio] even after Television Centre was opened [in the summer of 1960]” (p. 32).

Television was expensive to buy into: the “cheapest Ferguson 17” television receiver” in an advertisement from 1957 “cost £72.9s, including purchase tax” (p. 5). Briggs compares the increased uptake of TV to the ownership of refrigerators and washing machines - 25% of households in 1955, 44% in 1960 - as well as cars (p. 6). So there was more going on that what’s often given as the reason TV caught on - ie the chance to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953. The sense is of new prosperity, or at least an end to post-war austerity. Television was part of a wider cultural movement. The total number of licences issued (radio and TV) rose steadily through the period covered, from 13.98 million in 1956 to 17.32 million in 1974 (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). By 1974, the Report of the Committee on Broadcasting Coverage chaired by Sir Stewart Crawford felt, according to Briggs, that,

“People now expected television services to be provided like electricity and water; they were ‘a condition of normal life’.” (p. 998)

This increase in viewers and therefore in licence fee revenue, plus the competition from ITV, led to a change in attitude at the BBC about the sort of thing they were doing. Briggs notes that the experimentalism of the early TV service gave way to more and more people speaking of “professionalism” - skill, experience and pride in the work being done (p. 24). I’m struck by how those skills was shared and developed:

“The Home Services, sound and television, gain … from the fact that they are part of an organisation of worldwide scope [with staff] freely transferred … from any one part of the corporation to another [meaning that Radio and TV had] a wide field of talent and experience to draw upon in filling their key positions”. (pp. 314-15)

There are numerous examples of this kind of cross-pollination. Police drama Dixon of Dock Green was produced by the Light Entertainment department. Innes Lloyd became producer of Doctor Who at the end of 1965 after years in Outside Broadcasts, which I think fed in to the contemporary feel he brought to the series, full of stylish location filming. Crews would work on drama, then the news, then Sportsview, flitting between genre and form. Briggs cites a particular example of this in two programmes initiated in 1957 following the end of the “toddlers’ truce”.

For years, television was required to stop broadcasting between 6 and 7 pm so that young children could be put to bed and older children could do their homework. But that meant a loss in advertising revenue at prime time, so the ITV companies appealed to Postmaster General Charles Hill, who was eventually persuaded to abolish the truce from February 1957. But what to put into that new slot?

“Both sides [ie BBC and ITV] recognised clearly that if viewers tuned into one particular channel in the early evening, there was considerable likelihood that they would stay with it for a large part of the evening that follows.” (Briggs, p. 160)

The BBC filled the new gap with two innovative programmes aimed at grabbing (and therefore holding) a very broad audience. From Monday to Friday, the slot was filled by Tonight, a current affairs programme that basically still survives today as The One Show. The fact that it remains such a staple of the TV landscape can hide how revolutionary it was:

“Through its magazine mix, which included music, Tonight deliberately blurred traditional distinctions between entertainment, information, and even education; while through its informal styles of presentation, it broke sharply with old BBC traditions of ‘correctness’ and ‘dignity’. It also showed the viewing public that the BBC could be just as sprightly and irreverent as ITV. Not surprisingly, therefore, the programme influenced many other programmes, including party political broadcasts.” (p. 162)

Briggs argues that part of the creative freedom came because Tonight was initially made outside the usual BBC studios and system, as space had been fully allocated while the truce was still in place. The programme was made in what became known as “Studio M”, in St Mary Abbots Place, Kensington. But the key thing is that this informality, the blurring of genre, spread.

“This [1960] was a time when old distinctions between drama and entertainment were themselves becoming at least as blurred as old distinctions between news and current affairs and entertainment.” (p. 195)

|

| Jon Pertwee, Adam Faith Six-Five Special (1958) |

“along with a number of other Saturday programmes, it [Six-Five Special] helped to reconstruct the British Saturday, which had, of course, begun to change in character long before the advent of competitive television [and was, with Grandstand, part of] a new leisure weekend.” (p. 199)

Elsewhere, Briggs notes the impact of TV - especially of ITV - on other forms of entertainment: attendance at football matches and cinemas dropped, with many cinemas closing (p. 185). Large audiences of varied ages were becoming glued to the box. I’d dare to suggest that this was not a “reconstruction” but the invention of Saturday, the later development of Juke Box Jury, Doctor Who, The Generation Game etc all part of a determined, conscious effort to compete with ITV with varied, engaging, good shows.

(On Sundays, the BBC continued to honour the truce, with no programming in the 6-7 slot that might compete with evening church services. From October 1961, the slot was taken by Songs of Praise.)

One key way of making good television was to write especially for the small screen. Briggs, of course, cites Nigel Kneale in this regard - though his The Quatermass Experiment and Nineteen Eight-Four are covered in Briggs’ previous volume. But Stuart Hood in A Survey of Television (1967) notes how sitcom grew out of the demands that TV placed on comedians:

"the medium is a voracious consumer of talent and turns. A comic who might in the [music or variety] halls hope to maintain himself with a polished routine changing little over the years, embellished a little, spiced with topicality, finds that his material is used up in the course of a couple of television appearances. The comic requires a team of writers to supply him with gags, and invention" (Hood, p. 152)

Briggs has more on this. For example, Eric Maschwitz, head of Light Entertainment at the BBC, remarked in 1960 that,

“We believe in comedy specially written for the television medium [and recognise] the great and essential value of writers, [employing] the best comedy writing teams [and] paying them, if necessary, as much as we pay the Stars they write for” (Briggs, p. 196-97)

Briggs makes the point on p. 210 that, “The fact that the scripts were written by named writers - and not by [anonymous] teams - distinguished British sitcom from that of the United States.” Some of these writers, such as Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, became household names. Frank Muir and Denis Norden appear, busy over scripts, in Richard Cawston’s documentary This is the BBC (1959, broadcast on TV in 1960): these are writers as film stars.

Hancock’s Half Hour (written by Galton and Simpson) and Whack-o (written by Muir and Norden) were, Briggs says, among the most popular TV programmes of the period, but he also explains how a technological innovation gave Hancock lasting power.

In August 1958, the BBC bought its first Ampex videotape recording machine. At £100 per tape, and with cut (ie edited) tapes not being reusable, this was an expensive system and most British television continued to be broadcast live and not saved for posterity. (Briggs explains, p. 836n, that Ampex was of more practical benefit in the US, where different time zones between the west and east coasts presented challenges for broadcast.)

From July 1959, Ampex was used to prerecord Hancock’s Half Hour, taking some of the pressure of live performance off its anxious star (p. 212). Producer Duncan Wood, who’d also overseen Six-Five Special, then made full use of Ampex to record Hancock’s Half-Hour out of chronological order,

“allowing for changes of scene and costume … Wood used great skill also in employing the camera in close-ups to register (and cut off at the right point) Hancock’s remarkable range of fascinating facial expressions … Galton and Simpson regarded the close-up as the ‘basis of television.’” (p. 213)

Prerecording allowed editing, which allowed better, more polished programmes. What’s more, prerecording meant Hancock’s Half-Hour could be - and was often - repeated, even after his death. The result was to score particular episodes and jokes - “That’s very nearly an armful” in The Blood Donor - into the cultural consciousness. Another, later comedy series, Dad’s Army, got higher viewing figures when it was repeated (p. 954).

|

| Clive Dunn, Michael Bentine It's a Square World (1963) |

Briggs says of the appeal of the later Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which he insists on referring to as “the Circus” rather than the more common “Python”) that,

“It took basic premises and reversed them. It’s humour, which was visual as much as verbal, again often succeeded in fusing both.” (p. 950)

More than that, it was comedy that spoofed and subverted the structures and furniture of television itself. In this, it surely owed a big debt to Bentine.

He’s not the only one to have been rather overlooked in histories of broadcasting. I’ve seen it said in many different places that Verity Lambert, first producer of Doctor Who, was also at the time,

“the BBC’s youngest, and only female, drama producer” (Archives Hub listing for the Verity Lambert papers)

Yet Briggs cites Dorothea Brooking and Joy Harington as producers of “memorable programmes” for the children’s department, referring to several dramas adapted from books. Harington had also produced adult drama - for example, she oversaw A Choice of Partners in June 1957, the first TV work by David Whitaker (whose career I am researching). In early 1963, “drama and light entertainment productions for children were removed from the Children’s Department,” says Briggs on page 179, with this responsibility going to the newly reorganised Drama and Light Entertainment departments respectively. Lambert may have been the only female producer in the Drama Department at the time she joined the BBC in June 1963. Except that Brooking produced an adaptation of Julius Caesar broadcast in November 1963, and Harington was still around; she produced drama-documentary Fothergale Co. Ltd, which began broadcast on 5 January 1965.

(Paddy Russell’s first credit as a producer was on The Massingham Affair, which began broadcast on 12 September 1964. Speaking of female producers, Briggs mentions Isa Benzie and Betty Rowley, the first two producers of the long-running Today programme on what’s now Radio 4 (p. 223). My sense is that there are many more women in key roles than this history implies.)

Stripped of responsibility for drama and light entertainment, the children’s department was incorporated into a new Family Programming group, headed by Doreen Stephens. According to Verity Lambert, this group was envious of Doctor Who - a programme they felt that they should be making. When, on 8 February 1964, an episode of Doctor Who showed teenage Susan Foreman attack a chair with some scissors, it was felt to break the BBC’s own code on acts of imitable violence. As Lambert told Doctor Who Magazine #235,

“The children’s department [ie Family Programming], who had been waiting patiently for something like this to happen, came down on us like a ton of bricks! We didn’t make the same mistake again.”

Lambert had to write Doreen Stephens an apology, so it’s interesting to read in Briggs that Stephens didn’t think violence on screen was necessarily bad. In a lecture of 19 October 1966, she spoke of “overcoming timidity” in making programmes, and believed that,

“violence and tension [don’t] necessarily harm a child in normal circumstances [while] in middle-class homes of the twenties and thirties, too many children were brought up in cushioned innocence … protected as much as possible from all harsh realities.” (Briggs, p. 347).

|

| "Compulsive nonsense" Doctor Who (1965) |

“The university lecturer Edward Blishen called Doctor Who ‘compulsive nonsense’ [footnote: Daily Sketch, 3 July 1964, quoting a Report published by the Advisory Centre for Education], but there was often shrewd sense there as well. At its best it was capable of fascinating highly intelligent adults.” (p. 424)

Beyond the specific subsection, there are other insights into early Doctor Who, too. For example, Briggs tells us that,

“nearly 13 million BBC viewers had seen Colonel Glenn entering his capsule at Cape Canaveral before beginning his great orbital flight [as the first American in space, 20 February 1962]. An earlier report on the flight in Tonight had attracted the biggest audience hat the programme had ever achieved, nearly a third higher than the usual Thursday figure [footnote: BBC Record, 7 (March 1962): ‘Watching the Space Flight’’]” (p. 844)

Could this have inspired head of light entertainment (note - not drama) Eric Maschwitz to commission - via Donald Wilson of the Script Department - Alice Frick and Donald Bull to look into the potential for science-fiction on TV. Their report, delivered on 25 April that year, is the first document in the paper trail that leads to Doctor Who.

Then there is the impact of the programme once it was on air. On 16 September 1965, Prime Minister Harold Wilson addressed a dinner held at London’s Guildhall to mark ten years of the ITA - and of independent television. Part of Wilson’s speech mentioned programmes that he felt had made their mark. As well as Maigret, starring Wilson’s “old friend Rupert Davies”,

“It is a fact that Ena Sharples or Dr Finlay, Steptoe or Dr Who … have been seen by far more people than all the theatre audiences who ever saw all the actors that strode the stage in all the centuries between the first and second Elizabethan age.” (Copy of speech in R31/101/6, cited in Briggs, p. 497).

Two things about this seem extraordinary. One, Wilson - who was no fan of the BBC, as Briggs details at some length - quotes four BBC shows to one by ITV. And at the time, Doctor Who was not the institution it is now, a “heritage brand” of such recognised value that its next episode will be a major feature in the BBC's centenary celebrations this October. When Wilson spoke, this compulsive nonsense of a series was not quite two years-old.

But such is the power of television...

More by me on old telly:

- Nigel Kneale: a centenary celebration

- The influence of The Inheritors by William Golding on the first Doctor Who story

- A Survey of Television by Stuart Hood

- Mary Whitehouse vs Doctor Who

- Starlight Days, by Cecil Madden

- Writing for Television, by Sir Basil Bartlett

- The Intimate Screen, by Jason Jacobs

- I’m Just the Guy Who Says Action, by Alvin Rakoff

Saturday, May 28, 2022

Rosewater, by Tade Thompson

This is a gripping, intelligent thriller, full of big, mad ideas and images. The world Thompson has created is rich enough for multiple stories - this is the first of a trilogy, and in the closing pages we discover someone close to Kaaro does not think of herself as a supporting character but is the heroine of her own tale.

Bayo Gbadamosi's reading of the audiobook is especially good, giving voice to an array of different characters. It's suspenseful, it's weird and visceral, and has that brilliant science-fiction thing of being at once utterly extraordinary and also tangibly real.

Rosewater won the Clarke Award in 2019. Other books on the shortlist were Semiosis by Sue Burke, Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, and The Loosening Skin by Aliya Whiteley.

Friday, May 27, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #578

Had it not been for this exciting announcement, the cover would probably have gone to Peter Cushing, star of the 1960s Dalek movies that are being re-released this summer. There is lots about the films this issue, including two things by me.

In "Sets and the City", Rhys Williams and Gav Rymill recreate the sets from the 1965 film Dr Who and the Daleks, with commentary by me and Rhys. This month's "Sufficient Data" infographic by me and Ben Morris charts actors from the first Dalek movie who were also in TV Doctor Who.

(By nice coincidence, almost exactly 20 years ago, my first ever work for DWM was a feature on that first Dalek movie and big-screen Doctor Who generally. That was a cover feature, too.)Plus, in "Hebe Monsters", I speak to Ruth Madeley about playing Hebe Harrison, new companion to the Sixth Doctor in his latest audio adventures.

Given all this, they've also put a photo of niceish me on page 3, taken by the Dr.

Sunday, May 01, 2022

Amongst Our Weapons, by Ben Aaronovitch

What I especially like is how this standalone adventure still moves the series on, with Peter's imminent fatherhood creating ripples for the whole series, and then a quiet word from another character at the end promising more radical shake-ups to come. I also really like the sense of Peter trying to make connections between different magical communities, breaking down the idea so common to fantasy of wizarding as an elite.

The Waterstones edition includes a bonus story, "Miroslav's Fabulous Hand", narrated by Peter's mentor Nightingale and set just before and then during the Second World War. It's thrilling in itself - like an old-school James Bond adventure - but also exciting to see some of Nightingale's early life in more detail. This sort of thing could support a whole novel of its own. (See also what I said about the recent novella, What Abigail Did That Summer.)

By coincidence, I finished this while the Dr is on holiday in Thessaloniki, which is where I was in 2011 when I read the first Rivers of London book. By coincidence, the Dr now works at one of the places featured in this new book. By coincidence, as I was making my way to the Nigel Kneale centenary event last week, I got to the reference on page 218 to "the original Quatermass".

Thursday, April 28, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #577

A lot of attention has been given to Doctor Who Christmas specials, but to date 14 episodes have first been broadcast on Christmas Day, while 20 have premiered on Holy Saturday (the day between Good Friday and Easter Sunday):

- 28 March 1964 - Mighty Kublai Khan

- 17 April 1965 - The Warlords

- 9 April 1966 - The Hall of Dolls

- 25 March 1967 - The Macra Terror Episode 3

- 13 April 1968 - Fury from the Deep Episode 5

- 5 April 1969 - "The Space Pirates" Episode 5

- 28 March 1970 - Doctor Who and the Silurians Episode 2

- 10 April 1971 - Colony in Space Episode One

- 1 April 1972 - The Sea Devils Episode Six

- 21 April 1973 - Planet of the Daleks Episode Three

- 13 April 1974 - The Monster of Peladon Part Four

- 29 March 1975 - Genesis of the Daleks Part Four

- 26 March 2005 - Rose*

- 15 April 2006 - New Earth*

- 7 April 2007 - The Shakespeare Code

- 11 April 2009 - Planet of the Dead

- 3 April 2010 - The Eleventh Hour*

- 23 April 2011 - The Impossible Astronaut*

- 30 March 2013 - The Bells of Saint John*

- 15 April 2017 - The Pilot*

Six of those (marked with an asterisk) were the first of a new series, using Easter as part of the launch. Planet of the Dead (2009) and this year's Legend of the Sea Devils were special, one-off episodes for the Easter weekend.

Legend of the Sea Devils is the first episode of Doctor Who to debut on Easter Sunday itself. And the 1993 repeat on BBC Two of Revelation of the Daleks Part Four is the only episode of Doctor Who broadcast on terrestrial TV on Good Friday.

Monday, April 25, 2022

Skyward Inn, by Aliya Whiteley

A long time ago, Jem escaped her home in Devon and young son to cross through the Kissing Gate and journey into space. There she met and bonded with an alien called Isley, then brought him home to run a pub, the Skyward Inn, and reconnect with her own people. But the "brew" that Isley supplies has unusual properties, forging connections across time and memory, even giving visions of the future. As a disease takes hold of the Earth, the community starts to break down, people together and yet somehow utterly alone...

As strange and haunting as Whiteley's previous books, Skyward Inn is full of threat just under the surface, a pervasive wrongness that we can't always quite touch. The last section plays out as a nightmare, as unsettling as any Kneale. It's horrible yet beautiful, too - the prose full of feeling and pathos. We're made to understand why people make the awful choice to surrender entirely to the thing that's happening. The ending hangs on our belief in the strength of a connection between two individuals on separate planets and in different periods of time; it's brilliant.

The book owes something to Jamaica Inn, and is about the cross-pollination cultures. At its heart is the colonisation of another, populated world, its native people not resisting human invasion. As with previous Whiteley, that passivity is deeply unsettling. But this is all mirrored with an incursion by humans from across the boundary wall round Devon (now known as the "Western Protectorate"). There's lots on "good" immigrants bringing needed skills and expertise, deemed more worthy of acceptance than other individuals. There's lots on dysfunctional families and how we choose our connections. There's lots about how we interact and are shaped by interaction. We are our connections.

Sunday, April 24, 2022

Nigel Kneale: A Centenary Celebration

The first panel, "Nigel Kneale, Quatermass and the BBC", was chaired by Kneale biographer Andy Murray and featured Dick Fiddy from the BFI, Toby Hadoke and comedian Johnny Mains - the latter daring to admit that he doesn't much like Doctor Who. Kneale famously hated that series, but many of us got into Kneale's work via Doctor Who. I've been trying to puzzle out why, and think a lot of fandom - of anything - is trying to recapture the strong feelings of our past. For those thrilled and terrified by Doctor Who as kids, Kneale offers a grown-up version of those feelings, and - since he was so often borrowed from - an understanding of how they were kindled.

The panel was a good, breezy introduction to Kneale and the impact of his work on television in the 1950s, though a lot of the ground here was familiar to me from Toby's recent Radio 4 Extra programme, Remembering Nigel Kneale, and Cambridge Festival's "Televising the future: Nineteen Eighty-Four and the imagination of Nigel Kneale". I'd also just read Andrew Pixley's 1986 interview with Kneale.

Next up, we watched the extraordinary opening episode of The Quatermass Experiment from 1953 (available on the Quatermass Collection DVD set). It's a while since I'd last seen this, and I'd forgotten how blurry, clunky and techbnobabble-heavy its early scenes are as we watch serious, posh scientists at their desks in a tracking control room. But that soon gives way to the extraordinary sight of a house half-demolished by the world's first crewed space rocket. We see before the characters on screen that there's an old woman trapped in the exposed upstairs; she's played by Katie Johnson who two years later was the similarly dotty Mrs Wilberforce in The Ladykillers, only without her scene-stealing cat. It's just one of a number of well-observed comic characters enlivening the serious horror plot, adding a touch of realism - and fun - to the fantasy.

Having read The Intimate Screen by Jason Jacobs, I can understand why The Quatermass Experiment made such an impact: an original drama for television, rather than an adaptation of a stage play or book, that makes full use of the strengths of the medium to conjure an intimately creepy atmosphere. It's so busy, so populous, so nakedly ambitious - and all broadcast live. All these years later, it is thrilling. No wonder it stuck so powerfully with those who saw it at the time. As several panelists said, Quatermass was a thing that terrified our parents, that we first heard about from them decades afterwards - a folk memory of horror. (My mum says the girls at her school would make a lot of noise at the start of each episode, so the grown-ups in charge would not hear the warning of it not being suitable...)

Next up was Tom Baker in a bookish office to narrate Kneale's short story "The Photograph", in a 1978 episode of Late Night Story - a sort of grown-up Jackanory. It's an unsettling story about a sick child, but I was mostly struck by how little Baker blinked throughout what seemed to be a single take (and presumably involved him reading the story off an autocue).

Then Douglas Weir discussed the the new restoration of Nineteen Eighty Four (1954). The audience gasped at a particular example showing Peter Cushing's Winston Smith walking through Hampstead. The version screened by BBC Four a few years ago had Cushing moving through what looked like silver fog; the restored version shows him moving between trees, individual leaves crisp and clear. (I'm on the new Blu-ray release, by the way, just about audible asking Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray the question about Kneale's never-made scripts.)

Next was the panel "From Taskerlands to Ringstone Round – Nigel Kneale in the 70s", chaired by Howard David Ingham with panelists William Fowler, Una McCormack and Andrew Screen. I've been guilty of overlooking Kneale's 1970s output - The Stone Tape (1972), which I'd at least seen, and the anthology series Beasts (1976), which I haven't yet. That led into a screening of Murrain, Kneale's contribution to a 1975 anthology, Against the Crowd (included on the DVD release of Beasts).

David Simeon - who sadly couldn't be at yesterday's event - plays a vet called to a small village by a farmer played by Bernard Lee from the James Bond films. The farmer has some sick pigs and his water supply has dried up, plus a young boy in the village has had something like flu for a month. The farmer and the villagers think this all the work of a local woman, played by Una Brandon-Jones (who I recognised at once as Mrs Parkin in Withnail & I). The villagers want the vet's help in dealing with her; he's determined to champion science over superstition, insisting that "We can't go back" to the old ways. It's a compelling piece: real, sometimes funny and increasingly sinister. With a start, I recognised some of the scenery: the Curious British Telly site says Murrain was recorded in Wildboarclough, not far from where I now live. A local film for this local person, indeed.

Then Matthew Sweet chaired a panel on "Kneale on Film" with panelists Jon Dear, Kim Newman and Vic Pratt. This covered a lot of stuff I didn't know about: Kneale's work on the movie version of stage plays Look Back in Anger (1959) and The Entertainer (1960), and the mutiny-at-sea story HMS Defiant (1962) - all a long way from the weird-thriller stuff. Because of that, I'd not been much interested; the panel made me want to look them out and understand the weird stuff in context. I want, too, to see his last work, a 1997 episode of legal drama Kavanagh QC.

A clip from the movie version of The Quatermass Xperiment ((1955) showed infected astronaut Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth) stalk a Little Girl (Jane Asher), who offers it imaginary cake. Asher then joined us to discuss this early role and her later, more prominent part in The Stone Tape (1972) - which was then shown in full. I'd seen this before, but it was fascinating to see beside Nimbos, who didn't know what was coming, and in the context of the day's other offering. Again what struck me was how funny it was, especially the visual gag of Reginald Marsh's hands being outlandish colours as he experiments with dyes. Toby Hadoke pointed out that Neil Wilson appears as a salt-of-the-earth security guard having been seen as a salt-of-the-earth policeman in The Quatermass Experiment, so I wonder how much Kneale consciously used the same actors over the years.

This was followed by a live reading of Kneale's 1952 radio play, You Must Listen. Mark Gatiss played the lawyer who has a new telephone installed in his office, only to find he can hear a young woman talking sauce to an unheard lover. Again, it's very funny, the lawyer embarrassed and outraged but the telephone staff all keen to listen in on this rude stuff. And then, as before, it becomes ever more sinister as we realise this saucy woman is an echo from the past. In that sense, it dovetails with The Stone Tape from 20 years later, and with elements of the other stuff we'd seen. How well chosen all these examples were; we could see we were engaged in an experiment ourselves, to trace the resonant echoes of Kneale.

By this time Nimbos and I were flagging as the short breaks between screenings had not been long enough for us to eat any food, and I was getting a bit wobbly. So we sadly missed the panel on “'The inventor of modern television': Kneale’s influences and Legacy" chaired by Jennifer Wallis with panelists Stephen Gallagher, Mark Gatiss, Andy Murray and Adam Scovell. The day ended with a screening of the movie Quatermass & The Pit (1967), and then much natter in the bar.

It was all a bit overwhelming. There was the sheer amount of stuff covered and shown, but also the way the selection encouraged us to tease out shared themes, techniques, stylistics. Then there was the visceral thrill of being in company, catching up with so many friends. I had a long drive home today, passing close to Wildboarclough and its Murrain, brain abuzz from things learned and spotted and argued. That's the thing about Kneale, who died in 2006, and the stuff he wrote that was largely screened long before I was born...

It is potent. It is alive.

Tuesday, April 19, 2022

The Far Country, by Nevil Shute

In Australia, sheep farmer Jack Dorman finally pays off decades of debt and - despite a large tax bill to come - realises he is now wealthy. His wife Jane is worried about her elderly Aunt Ethel back in England, who she's not seen in 32 years (when Ethel was the sole member of Jane's family to back her relationship with Jack). Jane intuits that Ethel is short of money, so the Dormans, who've regularly sent Ethel letters and cake mix, now send her £500.

Things are far worse than they could imagine, and Ethel is starving to death in her nice house in Ealing, having sold most of her furniture and anything else of value from her days abroad. Ethel's granddaughter, Jennifer Morton, finds her in this state and cares for the old woman in her last days. But the book is pretty blunt about what has done for this poor woman: having once lived a rather grand life in Petersfield and then as a dutiful wife of empire out in Burma, she's been left destitute and unnoticed by, er, the new National Health Service. The independence of India has also meant the end of her pension. It's as if no one was neglected before the NHS; that before the welfare state there was no need of welfare. Or perhaps there's something more sinister: that if only we still had an empire and people knew their place, this sort of thing wouldn't happen to someone of her class.

The war is also to blame, but the privations suffered in England - which are ever increasing, long after the end of the war - seem to be the fault of the post-war government so far as the author is concerned. Jennifer works for a ministry, and we're told,

"It was manifestly impossible for anyone who derided the Socialistic ideal to progress very far in the public service; if a young man aimed at promotion in her office he felt it necessary to declare a firm, almost a religious, belief in the principles of Socialism." (p. 91)

It's quite a claim, but really it's Shute who is being unfairly partisan. The sense is of an old, glorious England now lost to the awful unfairness of egalitarianism. Dying, Ethel tells Jennifer,

"It's not as if we were extravagant, Geoffrey and I. It's been a change that nobody could fight against, this going down and down. I've had such terrible thoughts for you, Jenny, that it would go on going down and down and when you are as old as I am ... you'll think how very rich you were when you were young." (p. 71)

When the old woman dies, Jennifer's father goes through her things and finds a telling document - a recipe for a cake given to Ethel on her wedding day.

"What a world to live in, and how ill they must have been! His eyes ran back to the ingredients. Two pounds of Jersey butter... eight weeks' ration for one person. The egg ration for one person for four months... Currants and sultanas in those quantities; mixed peel, that he had not seen for years. Half a pint of brandy, so plentiful that you could put half a pint into a cake, and think nothing of it. ... He had eaten such cakes when he was a young man before the war of 1914, but now he could hardly remember what a cake like that would taste like." (p. 77)

The irony, of course, is that this woman starved to death, with only the cake mix to sustain her.

Ethel leaves her new money to Jennifer, making the girl promise to use it to visit Jane in Australia, and perhaps look for a better life there - like the one Ethel once knew in England. The doctor who treated Ethel is also leaving the country for a better life but Jennifer has reservations about leaving her elderly parents. Others suggest Australia will "probably be all desert and black people" (p. 95), or make an economic case for the value of migrants as an investment made by a particular country.

"For eighteen years somebody in this country fed you and clothed you and educated you before you made any money, before you started earning. Say you cost an average two quid a week for that eighteen years. You've cost England close on two thousand pounds to produce. ... Suppose you go off to Canada. You're an asset worth two thousand quid that England gives to Canada as a free gift. If a hundred thousand like you were to go each year, it'ld be like England giving Canada a subsidy of two hundred million pounds a year. It's got to be thought about, this emigration." (p. 89)

Despite this, Jennifer sets off to Australia for a temporary visit, certain she will then return home. At 24, she has never eaten grilled steak until boarding the ship - which comes as a great surprise to the Australians (p. 135). She in turn thinks very highly of their modest work in farming and producing food. A lot is made of the virtue of hard graft. The Dorman's have become wealthy after 32 years of toil, and repeatedly say they're glad that wool prices will soon fall so that their children don't end up too indolent. At the end of the book, Jennifer is appalled by a man visiting a doctor in the NHS wants,

"medicine and a certificate exempting him from work because he couldn't wake up in the morning." (p. 314)

Yet on the very same page, Jennifer organises things so that the doctor in question can have more lunches and dinners away from his patients, helping him to bunk off. And then,

"She was staggered to find out how much her mother's illnesses had cost, how much her father had been paying out in life insurance premiums for her security (pp. 314-5)

- presumably under the old, unjust system that the NHS replaced.

In Australia, there is no desert and there are no aboriginal people, though migrants from eastern Europe are treated as a lower order. Jennifer is welcomed by the Dormans, and cannot persuade their young daughter that a trip to England will only be a disappointment. Then there's a serious accident and no doctor available to help two men desperately in need. Carl Zlinter, a Czech immigrant working the land, was a doctor in his own country before serving with the Nazis, but he is not allowed to practice in Australia without retraining for three years. With the men in desperate peril, Jennifer assists Zlinter in carrying out highly risky operations to save the two men's lives, but one of them doesn't survive.

As an inquest looks into this and threatens to deport Zlinter, he gets closer to Jennifer, and is also haunted by the discovery of a gravestone bearing his own name and place of origin. It's for a man who died some decades previously, on the cusp of living memory. Zlinter is soon on the trail of the surviving, elderly people who might have known his namesake and can shed light on his story...

This particularly struck a chord because I'm researching the life of David Whitaker, who in 1971 adapted this novel for Australian TV (broadcast on ABC in 1972). Just as with Zlinter, I've been tracking down surviving paperwork and trying to speak to now-elderly people who might remember my man. There are many parallels between The Far Country and Whitaker's life. In 1950, he was living with his family in Ealing, streets away from the fictional address of Aunt Ethel. The house may also have had relics from India, where Whitaker's mother was born. The age difference between Zlinter and Jennifer is similar to that between Whitaker and his first wife June Barry. As with Jennifer, June Barry returned to Australia leaving Whitaker to work in Australia, with a shadow over their future together...

In fact, for all Jennifer clearly falls for Australia, there is plenty here to count against moving to this far country. There's the boredom of life on the farms, especially for the lone women keeping homes there. There's palpable danger given the lack of qualified doctors and the frequent risks of fire. There's also the philistine culture. Zlinter isn't the only one whose skills are overlooked in Australia. He buys a painting of Jennifer from Stanislaus Shulkin, a plate layer on the railway line who was once professor of artistic studies at the University of Kaunas.

Perhaps there's something here of the author: an engineer who also wrote novels, at once dirty-handed grafter and lofty man of arts. But surely it can't be a virtue to overlook the talents of Zlinter and Shulkin; it's squandering the investment, just as Shute argued before.

For all Australia offers a future to those prepared to work, Zlinter and Jennifer's happiness is secured by an inheritance that comes quite by chance and to which they're not entitled, requiring Zlinter to transact business with some slightly dodgy characters. He and Jennifer agree to keep the details secret - implicitly because they know that this is wrong. It's a necessary cheat because (just as with the Dormans), the rewards take a long time to win if they're to come at all. There are plenty of characters for whom things haven't worked out.

One reading of all this might be that Shute sets up an initial prejudice - bad old England against verdant, rich Australia - which he then proceeds to complicate and pick at, resulting in a richer, more complex portrait. But if so, the case is made in bad faith and the result is a very odd book.

Monday, April 18, 2022

What Abigail Did That Summer, by Ben Aaronovitch

Abigail Kamara is Peter Grant's 12 year-old cousin, as featured in several of the books about Grant, a London copper who investigates weird bollocks. This novella is what happens while Peter is away in Hereford (during the events of Foxglove Summer), looking into the disappearance of a bunch of kids her own age from Hampstead Heath. There's some suggestion this is going to riff on Pied Piper of Hamelin but it goes more The Stone Tape, but full of the usual smart, funny observation that makes the main series so compelling. There's a posh boy called Simon who prefers climbing trees to school work which particularly struck a chord.

Shvorne Marks is an excellent reader, with dour footnotes provided by Kobna Holbrook-Smith (who usually narrate's Peter's audiobook adventures). What strikes me is how easily Abigail could lead further adventures - as could many of the other rich and well-drawn characters in the series. Ben has created a whole world, one that could survive the death or retirement of its lead character. I'm all too aware off that as I begin Amongst Our Weapons...

On other titles in the series: