Thursday, June 13, 2024

Yellowface, by RF Kuang

Sunday, June 09, 2024

The Moving Toyshop, by Edmund Crispin (again)

"'Let's go left,' Cadogan suggested. 'After all, Gollancz is publishing this book.'" (p. 87)

It's more than a decade since I first read The Moving Toyshop and, having really enjoyed it then, I'm surprised how little stuck in the memory. One thing was the basic wheeze: Richard Cadogan stumbling drunk into a toyshop to find a dead body, only to return with the police to find the body and the whole toyshop gone. To solve the mystery, he calls on his friend, the eccentric Oxford don Gervase Fen.

Then there's the thrilling final sequence on a merry-go-round, borrowed by Alfred Hitchcock for Strangers on a Train. But sadly, between these two brilliant bookends, there's a lot of running around and literary gags that - though enjoyable - lack the mad and visual heft to linger.

Reading it after the two preceding novels (The Case of the Gilded Fly and Holy Disorders), it's also notable that this third instalment isn't set during the war as they are. We're not actually told when events take place - though the next novel, Swan Song, will reveal that The Moving Toyshop took place before the war and so precedes those two earlier novels.

"'Well, I'm going to the police,' said Cadogan. 'If there's anything I hate, it's the sort of book in which characters don't got to the police when they've no earthly reason for not doing so.'

'You've got an earthly reason for not doing so immediately.'

'What's that?'

'The pubs are open,' said Fen, as one who after a long night sees dawn on the hills. 'Let's go and have a drink before we do anything rash.'" (p. 50)

At one point, while incarcerated and with Cadogan unconscious, Fen amuses himself coming up with titles for further accounts of his adventures:

"'Fen steps in,' said Fen. 'The Return of Fen. A Don Dares Death (A Gervase Fen Story) ... Murder Stalks the University ... The Blood on the Mortarboard. Fen Strikes Back ... My dear fellow, are you all right? I was making up titles for Crispin.'" (p. 81)

Not even halfway through a third book and it's poking fun at the idea of this as a series; Fen established enough to be mocked just as much as anyone else in the literary world.

Friday, June 07, 2024

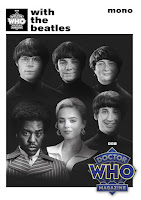

Doctor Who Magazine: Print the Legend

My two bits are:

pp. 18-21 Script to Manuscript: David Whitaker

The influences on Whitaker that helps to ensure the Doctor Who novelisations began at such a high standard, with some stuff I've picked up from my research into Garry Halliday as well as a previously unpublished photograph of Whitaker with Vincent Price.

pp. 22-23 The Final Chapter

Details of the Doctor Who related paperwork loaned to me by Whitaker's niece Melanie, including - reproduced in full - the surviving first page of his unfinished novelisation of The Enemy of the World, with permission of Whitaker's estate.

See also my biography, David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television.

Thursday, June 06, 2024

Making Sense of Suburbia through Popular Culture, by Rupa Huq

“Of recent UK offerings, The Sarah Jane Adventures, a spin-off from the long-running BBC science fiction series Doctor Who, was based in Ealing. Part of the show’s attraction was that such storylines of time travel and aliens could be unleashed in such an unlikely setting as a straight-laced, upstanding and ostensibly boring location.” (p. 130)

That Sarah Jane Smith hails from boring old Ealing (or, in The Hand of Fear, South Croydon) is juxtaposed against her adventures in all of time and space. It's a joke: after all her wild adventures, she ends up somewhere so ordinary.

Ealing is so ordinary and relatable that it could be anywhere - and indeed the Ealing scenes in The Five Doctors were actually filmed in Uxbridge, the Ealing scenes in The Sarah Jane Adventures were recorded in Penarth.

In the very first episode of Doctor Who, the mundane details of ordinary life - a policeman, a junkyard, a comprehensive school - create a credible, relatable frame for the sci-fi wonders that follow. Basically, the first half of the episode feels real so we buy the more outlandish stuff that follows. But again it's following that basic idea: we must leave the ordinary suburbs to go somewhere exciting.

And that's where the second kind of suburbia comes in. Huq quotes playwright Alan Ayckbourn on suburbia:

“It’s not what it seems, on the surface one thing but beneath the surface another thing. In the suburbs there is a very strict code, rules … eventually they drive you completely barmy.” Think of England: Dunroamin’ (BBC Two, 5 Nov 1991, dir. Ann Leslie)

The suburbs are a place on anxiety, the “suburban neurosis” outlined in the Lancet in 1938 by Stephen Taylor, senior resident medical officer at the Royal Free Hospital (and, er, my dad's godfather). Huq also charts similar ideas in Betty Friedan's influential The Feminine Mystique (1963). I can see these same ideas being explored in sitcoms of the 1970s, that sense of the suburb as a place of strangeness and secrets and danger.

In fact, I think The Sarah Jane Adventures and quite a lot of Doctor Who makes more use of this second kind of suburbia, where more is going on that meets the eye. With aliens and time travel and daft jokes aplenty, the whole point is that Ealing - or anywhere else - isn't boring. Which might be of some comfort to the local MP.

Anyway. More of this to come in the thing I'm working on...

Monday, June 03, 2024

A Short History of the World, by HG Wells

Earlier this year, I described the effect of time travel in Wells's The Time Machine (1895):

"It’s as if the traveller is perched on a bicycle in front of a cinema screen, working a lever to speed up the film being shown until it passes in a blur."

There, the film starts in the (then) present day and whizzes far into the future. The effect is much the same in A Short History of the World but we start from an estimated 1.6 billion years ago and whizz forward to the present. The intention, Wells says in the Preface, is that it should be read "straightforwardly almost as a novel" (p. iii).

That means we rattle through events and ideas quickly, most chapters just a few pages long. Wells admits that he has little access to histories of China and elsewhere, so there's an acknowledged western bias. Even so, its odd that some 50 pages - about one-sixth of the whole book - are devoted to the history of Rome, not least given the author's claim that,

"the whole Roman Empire in four centuries produced nothing to set beside the bold and noble intellectual activities of the comparatively little city of Athens during its one century of greatness" (p. 134).

The point, of course, is that Wells is using history to illuminate the (then) present, and Rome provides the template for the British Empire and the clash of the great powers.

"The Roman Empire was a growth; an unplanned novel growth; the Roman people found themselves engaged almost unawares in a vast administrative experiment ... In a sense the experiment failed. In a sense the experiment remains unfinished, and Europe and America to-day are still working out the riddles of world-wide statecraft first confronted by the Roman people." (p. 119)

In that mode, his chapter on Jesus as a historical rather than religious figure reads like a description of a Fabian social reformer. That's also true of his description of other prophets and thinkers, though he adds the caveat that a modern reader of their ideas may also find,

"much prejudice and much that will remind him of that evil stuff, the propaganda literature of the present time." (p. 82)

For all he covers a lot of ground concisely, Wells is careful not to draw too simple parallels or to make his history overly simplistic.

"It is well for the student of history to bear in mind the very great changes not only in political and moral matters that went on throughout this period of Roman domination. There is much too strong a tendency in people's minds to think of the Roman rule as something finished and stable, firm, rounded, noble and decisive. Macauley's Lays of Ancient Rome, SPQR, the elder Cato, the Scipios, Julius Caesar, Diocletian, Constantine the Great, triumphs, orations, gladiatorial combats and Christian martyrs are all mixed up together in a picture of something high and cruel and dignified. The items of that picture have to be disentangled. They are collected at different points from a process of change profounder than that which separates the London of William the Conqueror from the London of to-day." (pp. 119-20).

That disentangling includes his acknowledgement that only a small minority in Rome enjoyed the benefits and freedoms of the empire. He devotes considerable time to the myriad roles played by slaves in agriculture, mining, metallurgy, construction, road-making and on galleys, as well as working as guards and gladiators. What's more,

"The conquests of the later Republic were among the highly civilised cities of Greece, North Africa, and Asia Minor; and they brought in many highly educated captives. The tutor of a young Roman of good family was usually a slave. A rich man would have a Greek slave as librarian, and slave secretaries and learned men. He would keep his poet as he would keep a performing dog. In this atmosphere of slavery the traditions of modern literary scholarship and criticism, meticulous, timid and quarrelsome, were evolved." (p. 133)

That's surely a popular novelist having a dig at the pretensions of poets and critics of his own age. The novelist is also there in the sizeable imaginative leap of trying to get inside the heads of early humans to describe how they thought and felt about the world around them (Chapter XII, Primitive Thought) - an attempt later repeated by William Golding in The Inheritors and by the first Doctor Who story. Less credible is the novelist's odd conspiracy theory that, after Alexander conquered Egypt in 332 BCE,

"the Phoenicians of the western Mediterranean suddenly disappear from history - and as immediately the Jews of Alexandria and the other trading cities created by Alexander appear."(p. 94)

This, I suspect, is drawn from whatever racial theories Wells was reading. As I rather expected, there's quite a lot here on the geographical movements and cultural impact of particular ethnic groups such as the Aryans, detailing skin colour and other racial characteristics. The terminology used is similarly racist and of their time, and I already knew Wells was an enthusiastic eugenicist. But I think that makes it all the more notable when he endeavours to avoid prejudice. For example, there's his response to the wealth of evidence of early humans found in France and Spain:

"The greater part of Africa and Asia has never even been traversed yet by a trained observer interested in these matters and free to explore, and we must be very careful therefore not to conclude that the early true men were distinctly inhabitants of Western Europe or that they first appeared in that region." (p. 32)

Or, there's his caveat on outlining what he calls the "main racial divisions" of the neolithic world:

"We have to remember that human races can all interbreed freely and that they separate, mingle and reunite as clouds do. Human races do not branch out like trees with branches that never come together again. It is a thing we need to bear constantly in mind, this remingling of races at any opportunity. We shall be saved from many cruel delusions and prejudices if we do so. People will use such a word as race in the loosest manner, and base the most preposterous generalisations upon it. They will speak of a 'British' race or of a 'European' race. But nearly all the European nations are confused mixtures of brownish, dark-white, white, and Mongolian elements." (p. 45)

I was also struck by his defence of the latter:

"We hear too much in history of the campaigns and massacres of the Mongols, and not enough of their curiosity and desire for learning" (p. 202).

This all feels very pertinent given the context of the time in which Wells was writing. The chronology at the end of the 1934 edition ends with "Hitler becomes dictator of Germany [and] World Economic Conference in London" (p. 313), but Wells - for all he astutely identifies problems in the Treaty of Versailles leading to future conflict, warns of war,

"in twenty or thirty years' time if no political unification anticipates and prevents it" (p. 300).

Hitler is not mentioned in the main body of the text; he and Stalin were both added to the 1938 edition. My 1941 edition includes Chamberlain, Churchill and Roosevelt, as well as references to Disraeli and Kipling. In updating the book to cover events of less than a decade, he reaches further back into the past.

It's also interesting what revisions Wells didn't make to the 1941 edition: for example he doesn't add the discovery of Pluto to his description of the Solar System in chapter one. I find myself picking over what he might have added to a later edition, if he'd lived a little beyond 1946. The atomic bomb - a term Wells coined - would be key. His chapter on industrialisation would need something on automation and loom cards, now recognised as so crucial to the development of computers.

Oh, and his reference to the "fascinatingly enigmatical" Piltdown Man (p. 27) would get quietly cut.

In fact, I'd love to see a new version of this enterprise: a concise, breezy history of the whole world (not just the western bits), making sense of now based on what's gone before and pointing the way to the future...

See also:

Sunday, June 02, 2024

Athens

|

| View from our hotel |

Highlights of the trip for me were the things that engaged them. That includes staff at Manchester Airport spotting my son's sunflower lanyard and quietly, conscientiously making things a little easier for us all. Aegean Airlines were incredibly accommodating with families, such as ensuring that children on the flights got fed first and providing colouring books and card games.

Really, there was only one sour note to the trip. The Acropolis was very crowded and the narrow path up to it a bit of an ordeal, with many other tourists not behaving well - shoving past my daughter, standing on my feet so often I had to wash blood from my sandals, and ignoring ropes and signs closing off various bits of the site. It may just be that our pre-booked, mid-morning slot coincided with all the coach trips.

Other sites - the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Hadrian's library, the Greek Agora and its Roman counterpart - were bustling but less of a scrum. In contrast, we ducked into the Museum of Modern Greek Culture to escape from the sun and had the place pretty much to ourselves. It was a revelation, the various themed exhibits holding the children's attention for two hours.

I was wowed by the Acropolis Museum, where me and Lady Vader completed a treasure hunt of different representations of Athena and then had various games and activities. For the latter, we found a quiet corner on the second floor, where there's the awe-inspiring recreation of the Parthenon frieze and other ornamentation made up from original stonework and casts of the purloined pieces.

As we sat there, passing tourists kept voicing the same thought: once you see this incredible display, with the windows looking out on the Acropolis itself, it's hard to fathom how the British Museum can possibly object to sending its own bits of the Parthenon home.(The Lord of Chaos was much taken by the Lego version of the Acropolis on display on the floor below, where a pith-helmeted Lord Elgin can be seen nicking some of the sculptures - boo, hiss).

For all we explored the ancient past, we were also tracing more recent history - the corner of Syntagma Square where, in 2000, I first met the Dr's aunt and uncle (then residents of Athens, now sadly deceased), the bit of Monastiraki where in 2007 we whiled away an afternoon with my parents in a bar overlooking the Agora. I first went to Athens on a fancy school trip in 1989, when I was the same age as my son is now. Our trip to the Museum of Modern Greek Culture made me especially sensitive, I think, to that idea of interwoven, personal history.

At the same time, the coach-loads of tourists from America, Australia, Japan and wherever else make a different case. The Acropolis Museum focuses on the Greek history and the birthplace of democracy but there's little on why so many modern states trace a line back to this city, and how the ideas originated in Athens have been adapted. Uncivilised by Subhadra Das points out that ancient Athenians wouldn't recognise our modern political systems as "democratic"; I'd have liked to have seen more of the present in reading the past.

|

| House of Simon |

Thursday, May 23, 2024

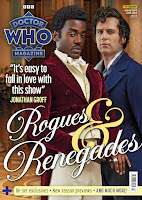

Doctor Who Magazine #604

That's followed by "Baby Love", in which I talk to the team about realising the episode's diminutive guest stars. There will be more from me about Space Babies later in the year...

And then, in "Music's Gonna Flood Back In!" - a line cut from towards the end of the final version of The Devil's Chord, fact fans - I interview Sam Dinley, music assistant to Doctor Who composer Murray Gold.

Sunday, May 19, 2024

The Doctor Who Production Diary - 1. The Hartnell Years, by David Brunt

"The number of nude photos needed for the Guardroom set has increased from three to six." (p. 647)

This massive, detailed day-by-day history of the making of Doctor Who is a great nerdy joy. The first volume covers the period from Monday, 2 November 1936 (the start of the BBC's regular Television service) to Friday, 4 November 1966 (the day before Patrick Troughton made his full debut as the Second Doctor, having been glimpsed in the closing moments of the episode broadcast the previous week).

In effect, it's a much expanded version of the 164-page production diary featured in Doctor Who: The Handbook - The First Doctor (1994) by David J Howe, Mark Stammers and Stephen James Walker. Indeed, Walker is the editor of this new volume, which is published by Howe's company, Telos. David Brunt looked again at the production files held at the BBC's Written Archives Centre used in that earlier version, and also looked more widely - there's an exhaustive list at the end of this volume of the files consulted for individual writers, actors and other personnel, as well as BBC departments.

I should probably declare an interest in that David's research at WAC overlapped my own for the biography of David Whitaker. We liaised a bit, compared notes and shared ideas, and I read a fairly early draft version of this book containing much less detail. There's plenty in the published volume that is new to me. In some instances, we looked at the same evidence and came to different conclusions.

For example, the book says that David Whitaker "has most likely been appointed as Doctor Who's story editor" by the time of his wedding on 8 June 1963 (p. 49). My guess is that if this were case he'd have been copied into the memo dated Monday, 10 June from head of serials Donald Wilson to everyone else involved at a senior level: assistant head of drama Norman Rutherford (head of drama Sydney Newman being away), drama department organiser Ayton Whitaker (no relation), associate producer Mervyn Pinfield, acting producer Rex Tucker and incoming producer Verity Lambert (who didn't start for another week). Maybe the story editor wasn't considered sufficiently senior for inclusion in this august company, but I make the case in my book for David Whitaker being assigned to Doctor Who on Monday, 17 June.

I'm especially impressed by pp. 104-105, where the weekly cycle of rehearsals, read-throughs and technical runs is spelled out. As far as I'm aware, there's no single document detailing this sequence and it's been deduced from scattered references in myriad different sources. Understanding that schedule illuminates much that follows. We can appreciate the frustration of actor William Russell being given a new six-page scene to learn on Thursday, 20 February 1964, the day before The Wall of Lies was recorded; it's additionally frustrating when we know that after a Thursday morning run-through of an episode for the producer and senior technical crew,

"the cast will normally be free to ... leave early that day." (p. 105)

The other thing that this book illuminates is the frantic spinning of multiple plates at any one moment. Most histories of Doctor Who - in Doctor Who Magazine or the Complete History, or on the DVDs and Blu-rays - scrutinise one story at a time. The Production History lays out how studio production on one story overlapped with filming for the next, the writing and editing of the story after that and planning and budgeting for stories months ahead. At the same time, there was press and publicity, and responses to enquiries about the episodes just aired.

Detailing the treadmill of production demonstrates, time and again, the problems caused by anyone holding things up, whether late scripts or delivery of props, or the repeated machinations of the Design Department to kill Doctor Who before it even started. It's dizzyingly, exhaustingly fraught. It's all the more impressive that Doctor Who was often so compelling and easy to see why working on this series burned through talent so quickly.

This day-by-day approach is very revealing and has made me make a whole tonne of connections. I'll give the example of one story, to show how it is in fact lots of stories and things happening at once.

On Thursday 26 May 1966, William Hartnell (Doctor Who), Michael Craze (Ben Jackson), Anneke Wills (Polly) and members of the guest cast were in Cromwell Gardens in Kensington for location filming on The War Machines. We're told that this included a high-shot filmed from upstairs at no. 50F (by arrangement with a Mrs Lessing there), and that,

"The location in Cornwall Gardens is diametrically opposite the property where Peter Purves is living at this time." (p. 603)

Hartnell spent that same morning in rehearsals on the preceding serial with Purves (Steven Taylor) and Jackie Lane (Dodo Chaplet). The Savages Episode 3 was then recorded in studio the following day. Both co-stars were being rather abruptly written out of the series, Purves the following week and Lane two weeks later in the middle of The War Machines. The prevailing atmosphere was not great, as Purves told me in 2013:

"I was very disappointed [to leave]. Later, I knew [producer] Innes [Lloyd] quite well and there was no animosity. But I didn't want to go. Bill [Hartnell] was furious. I remember him saying he'd make them change their minds. A few months later, he was gone, too." (Me, interview with Peter Purves for Doctor Who 50 Years - The Companions)

Given this, it's all the more astonishing that the production were there on Purves' doorstep, filming with his replacements.

Also present at the location filming that afternoon were William Mervyn (Sir Charles Summer), whose son Michael Pickwoad later designed more than one TARDIS and Mike Reid (uncredited soldier), later a comedian, host of Runaround and Frank Butcher in EastEnders and Dimensions in Time. There was more notable casting on this story. When the first episode of The War Machines was recorded in studio on 10 June, one of the extras in the Inferno nightclub was Alan Cassell, later the star of Australian TV's The Drifter, written by David Whitaker. Two weeks later, another extra left production during the lunch break to go for an X-ray and then didn't return for that evening's recording of Episode 3; Mike Yarwood is,

"now better known for his later TV career as an impressionist." (p. 620)

That week had been a little fraught anyway. On Monday, 20 June, the first day of rehearsals on the episode were disrupted by Hartnell "still feeling the after-effects" of filming in Cornwall the previous day for next story The Smugglers. Having completed work, he'd had a long trek back to London by train. His second-class ticket from Penzance (p. 606) seems extraordinary treatment for a veteran star of a series and came at a cost: his "travel fatigue" (as the Production Guide puts it) led to a delay in the usual schedule. On 6 July, William Mervyn wrote a letter to Lloyd suggesting that Hartnell should henceforth be transported by helicopter - for all the joking tone, it implies there had been a real problem.

Reading events day by day, I think it might have been the final straw for Lloyd. On 24 June, the day that The War Machines Episode 3 was in studio, the producer notified story editor Gerry Davis that, by arrangement with Hartnell's agent, the star would be absent from whatever episode was to be recorded on 11 February 1967 - in the event, The Moonbase Episode 2. But the problems caused to the schedule following filming in Cornwall surely affected the decision Lloyd was then involved in. On 15 July 1966, three weeks after that memo to Davis, Lloyd seems to have broken the news to Hartnell that his contract would not be extended beyond the next four-part story, The Tenth Planet. Hartnell told his wife the following day that he would be leaving Doctor Who.

I've pored over much of the original paperwork used here and thought I knew this stuff. This exhaustive diary tells a whole new story. Let's have volume 2 sharpish, please and thank you.

Saturday, May 18, 2024

Holy Disorders, by Edmund Crispin

"I AM AT TOLNBRIDGE STAYING AT THE CLERGY HOUSE PRIESTS PRIESTS PRIESTS THE PLACE IS BLACK WITH THEM COME AND PLAY THE CATHEDRAL SERVICES ALL THE ORGANISTS HAVE BEEN SHOT UP DISMAL BUSINESS THE MUSIC WASN'T BAD AS ALL THAT EITHER YOU'D BETTER COME AT ONCE BRING ME A BUTTERFLY NET I NEED ONE WIRE BACK COMING NOT COMING FOR LONG STAY GERVASE FEN." (pp. 3-4)

We learn that a local organist has been attacked and knocked unconscious, and that Vintner has also received an anonymous letter threatening that he will "regret" any trip to Tolnbridge. So, gun in hand, he heads to Tolnbridge (in Devon), stopping first at a London department store to acquire a butterfly net. There, he is set-upon by a would-be assassin in the midst of the sports equipment. In the ensuing battle, runaway footballs cause chaos on the lower floors of the store.

All this is within the first 10 pages, a mini-adventure like something from a silent comedy setting us up for the main event. As before, this is an arch and witty detective story, but much more in the John Buchan mould than its predecessor. One element of the plot involves a teenage girl drugged with marijuana to do the bidding of the villains, while another involves witch trials from 1705 and a modern-day coven led by a villainous priest, but really this is a shocker about Nazi spies working undercover in England. Oh, and Vintner meets a young woman in Tolnbridge and immediately falls in love.

For all it's fun, and peppered with literary allusions and jokes, the last few chapters are really suspenseful - Fen is kidnapped, badly beaten by the villains and there's added resonance here in the fact that these Nazis ruthlessly use gas to dispose of their victims. Rather than ill-fitting the light comedy / cost detective story stuff, this real-world horror works extremely well. The eccentric, idiosyncratic Fen is nonetheless a hero, still cracking jokes as the villains rough him up, in a manner that reminded me of James Bond in Casino Royale. There's something, too, of the plucky spirit of Went The Day Well? (1942).

"'Do talk English,' said Fen, with a touch of acerbity. 'And try to stop imagining you're in a book.'" (p. 218)

Sunday, May 12, 2024

Annie Bot, by Sierra Greer

Gosh, this is good — and thrilling, disturbing and difficult to put down. Annie Bot is all told from the perspective of a robot owned by 34 year-old Doug Richards. She’s a “Cuddle Bunny”, mentally and physically programmed to please him. Sensors score his displeasure out of 10, and we get a constant running total. The same is true of Annie’s own libido. Keep Doug happy and she will be happy, too… but he keeps giving out mixed signals.

Slowly, Annie learns to understand him — and herself.

Effectively, the book picks up where The Stepford Wives ends, told from the perspective of one of the robots. We’re often ahead of Annie in noting and processing things. For example, there are Doug's bookshelves:“It occurs to her, eventually, that Doug and all the other humans talk about their lives with a myopic intensity, sharing singular, subjective opinions as if they are each the protagonist of their own novel. They take turns listening to each other without ever yielding their own certainty of their star status, and they treat their fellow humans as guest protagonists visiting from their own respective books. None of the humans are satellites the way she is, in her orbit around Doug.” (p. 215)

“For fiction, he is long on Poe, Grisham, Wolfe, L'Amour, Hemmingway, Nabokov. There's a paucity of female writers and writers of color.” (p. 152)

Or there's a character they meet and seem to get on with, until Doug and Annie discuss the conversation later.

“'Could you tell she was trans?' he asks ... She waits, expecting him to explain why this is relevant, but he doesn't add anything more.” (p. 164)

But Doug has also allowed Annie to be ‘autodidactic’, and the more she experiences and reads, and the more that Doug treats her unfairly — or even with cruelty — the more she comes to question the strictures of her existence…

Fast-moving and suspenseful, this is also a novel of big ideas. Annie is just one of a whole world of robot slaves, including ‘Stellas’ for domestic housework, ‘Hunks’, ‘Nannies’, ‘Abigails’ and ‘Zeniths’. Then there’s the industry to support these machines: commercial interests, scientific research and even a robo-psychologist who helps humans and their robot partners — Dr Monica VanTyne is more counsellor to them both than engineer fixing robots in the style of Asimov’s Dr Susan Calvin.

We cover a lot of ground, touching on the ways different people are affected by or implicated in this system. I’ve just read Alex Renton’s Blood Legacy so was very conscious of the parallels with slavery. But I think this is also a novel in a particular tradition of sci-fi.

Earlier this year, I went to an event where Jared Shurin talked about his new Big Book of Cyberpunk. That includes a long and insightful introduction in which he grapples with what cyberpunk actually is, but at the event itself he suggested that the US and UK tended to have their own distinctive kinds of stories in this field. In the UK, those stories were often railing against Thatcher — the punk attitude to the fore. In the US, a lot of stories tended to focus on the knotty philosophical question of “Can I fuck my robot?”

See also:

Thursday, May 09, 2024

Doctor Who: Deathworld

"The First, Second and Third Doctors become caught in a temporal game of chess played between the President of Gallifrey and Death itself," says the blurb.

The cast includes Stephen Noonan as Doctor Who, Michael Troughton as Doctor Who and Tim Treloar as Doctor Who, with Katy Manning as Jo Grant, Jon Culshaw as Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart and Frazer Hines as Jamie McCrimmon.

Doctor Who - Deathworld is directed and produced by David O'Mahony. I was script editor on this lost story, having previously adapted Prison in Space and The Mega, and produced last year's The Ark and Daleks! Genesis of Terror.

Saturday, May 04, 2024

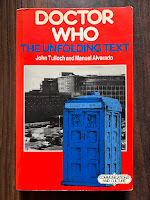

Doctor Who - The Unfolding Text, by John Tulloch and Manuel Alvarado

There’s a fun moment in the Doctor Who story Dragonfire when the Seventh Doctor is required to distract a guard. Some other adventuring hero might cosh the guard on the head but the Doctor instead politely asks him about the nature of existence.

The guard turns out to have strong opinions on the matter and the Doctor is soon out of his depth:

GUARD

You've no idea what a relief it is for me to have such a stimulating philosophical discussion — there are so few intellectuals about these days. Tell me, what do you think of the assertion that the semiotic thickness of a performed text varies according to the redundancy of auxiliary performance codes?

DOCTOR WHOYes.

Doctor Who and the Dragonfire by Ian Briggs (1987)

The question is drawn directly from an academic book on Doctor Who, in a section applying some ideas originated by Keir Elam — now professor of English literature at the University of Bologna.

“What Elam calls the semiotic ‘thickness’ (multiple codes) of a performed text varies according to the ‘redundancy’ (high predictability) of ‘auxiliary’ performance codes.”

While this might at first seem impenetrable, authors John Tulloch and Manuel Alvarado immediately unpick its meaning.

“Thus, for instance, if the sets, music and so on were simply to reinforce the actors’ performance without adding to it or inflecting it in the direction of new associations, but simply overlaid the acted ‘pace’ and ‘drama’ with their own, they would be relatively redundant, serving only to bind together the text’s temporal unfolding. On the other hand, in the Williams/Adams story, City of Death, the use of music and sets in the scenes featuring the Count and Countess was more entropic, drawing on motifs which some audience members recognised as ‘very forties’, and therefore potentially relocating the stolen art theme in terms of, say, The Maltese Falcon.” (The Unfolding Text, p. 249)

In fact, the production of Dragonfire might have learned something from this and benefited from the same kind of added richness.

I’ve been busy over the past fortnight researching and writing a bunch of things and The Unfolding Text has been useful on more than one. First published in 1983 to coincide with Doctor Who’s 20th anniversary (so covering what’s now one-third of Doctor Who’s history), it was part of a “communications and culture” range published by Macmillan and executive edited by Stuart Hall and Paul Walton. Alongside The Unfolding Text were an academic study of James Bond and titles such as The Politics of Information, Culture and Control and Reproduction Ideologies.

My memory of the book, having read it while doing English Literary Studies at UCLAN in the last millennium, was that it’s heavy going, that sentence spoofed in Dragonfire representative of the whole. There’s certainly a lot of technical language but this time I found it all enjoyably gossipy.

The authors spoke to cast and crew from the past and then-present of Doctor Who, and attended rehearsals and recording of the 1982 story Kinda. Their media studies approach is quite different from the interviews published in fanzines, Doctor Who Magazine and other sources from the time, which tended to focus on what happened when, building up a timeline of production. Here, we get deeper insights into the thinking behind creative choices and a sense of what these mean. That’s especially revealing when people involved in making Doctor Who talk about stories they didn’t work on.

How fascinating, for example, to hear Douglas Adams — script editor on Doctor Who 1978-79 before becoming the best-selling author of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — explain why he didn’t like Logopolis (1981), written by his successor.

“In comparison to what we were doing, the new ones [episodes] are terribly, terribly slow. We seem to have endless, endless wanderings round and round the same point. I think that, in the time we were there, there was this sheer weight of ideas we managed to pack in — the sheer number of events and things going on … In contrast, in Logopolis we … did seem to spend ages and ages wandering around and around and around the interior of the TARDIS.” (pp. 219-220)

Then there’s where all this wandering led. Adams says he'd expended considerable energy in clarifying the “final threat” of any given story and “what the villain actually wants” (p. 170). He could see that reintroducing the Master — in the story preceding Logopolis — made plotting much simpler because he’s effectively the “guy in the black hat” and we can take for granted that he’s up to something bad.

“But to my mind that in the end means ‘boring’ because why does a guy want to take over the universe? … At the end of Logopolis suddenly you had the Master broadcasting a message to the entire universe, which to me just doesn’t mean anything. There’s nothing you can visualise there, and there’s nothing that actually has any meaning in any real world.” (p. 171)

Logopolis still haunts my imagination but it’s fascinating to hear Adams explain what he saw as fundamental shortcomings, the issue of tangibility illuminating his time on the series and the stories that followed. The sense is that, had he stayed in post, he wouldn’t have commissioned Logopolis. And he could critique the story because, even after leaving Doctor Who, he kept on watching and puzzling over how to make it work.

So, these interviews offer us authoritative insight into Doctor Who. Yet there’s something odd about the authority of this book. I’m especially conscious of this as the author of books and magazine articles about Doctor Who, and rereading The Unfolding Text has sparked a whole load of thoughts about my approach to authority.

For example, in citing Adams, the authors of The Unfolding Text repeatedly refer to him as “Doug”. How we refer to people has an impact on the way we perceive what they say. “Doug” is not Adams’s name professionally — he was always credited as “Douglas” — and I’d never heard him referred to “Doug” elsewhere. That suggested that the authors were on particularly close terms with Adams, which might then explain why he’d been so candid. My sense of the authors’ authority was coloured by the way they used his name.

But I checked with Kevin Davies, editor of last year’s best-selling 42: The Wildly Improbably Ideas of Douglas Adams, who’d known Adams very well. And he told me that, no, Douglas wasn’t “Doug":

“I think it’s safe to assume the Unfolding Text guys didn’t really know him.”

And that recolours my sense of authority here: if the authors got that wrong, what else might not be right?

While the authors clearly had access to production and many members of the cast and crew, they lacked access to archive materials more readily available now. That leads to some errors of fact.

“Though Donald Wilson, head of series/serials, also hated the [first] Dalek story, Lambert went ahead on the grounds that the next planned story, Marco Polo, was not ready.” (p. 42)

For one thing, Wilson was head of serials — there was a separate head of series at the time. For another, Lambert wouldn’t have considered replacing Marco Polo with the Dalek story. When it began, Doctor Who alternated historical stories with sci-fi, so you couldn’t swap one for the other. In fact, the first Dalek story was brought forward to replace a serial then called The Robots.

Besides, I think the above is cribbing from a mistaken belief among fans that two-part The Edge of Destruction was commissioned at late notice to fit between the Dalek story and Marco Polo because of delays on the latter. We now know from contemporary paperwork held in the BBC Written Archives Centre that that isn’t what happened at all — which I go into at inordinate length in my recent book for the Black Archive.

The most striking issue of access in The Unfolding Text is how little the authors have been able to see of old episodes on which to base their judgements. Chapter 1 devotes a lot of time to the very first 25-minute episode, An Unearthly Child (1963), and a similar level of depth is given in Chapter 6 to the Fifth Doctor story Kinda (1982). Coverage of the Fourth and Fifth Doctor’s eras is pretty wide-ranging, I suspect because it’s a recent memory for the authors and those they spoke to rather than that they went back and watched episodes anew. Discussion of the Second and Third Doctors’ eras is predominately focused on one story each, neither of them particularly representative of that period of Doctor Who. From the index:

‘Krotons, The’ 61, 69, 74-81, 91-7

‘Monster of Peladon, The’ 9, 52-4, 86-91, 106, 114, 182-3, 188, 224, 280

How different things are today, with almost all of Doctor Who up on iPlayer for researchers to research and for readers to check. It's also easier to check the correct titles of stories — The Unfolding Text refers to Masque of Mandragola and Castravalva on occasion, but also spells them correctly on others. And it attributes a line of dialogue to the wrong production team:

“With the exception of the Troughton era, Doctor Who has fundamentally adhered to the original brief of Verity Lambert and David Whittaker (sic) that the Doctor should appear as a ‘citizen of the universe and a gentleman to boot’.” (p. 100)

I don’t mean to nit-pick: it’s more that these things all illuminate something I’m very aware of at the moment — how access to old episodes is changing the ways that fans can and do engage with Doctor Who’s rich history. In what I write now, I can direct readers to watch episodes for themselves rather than spelling out what happens, and I can leave them to judge for themselves rather than offering an opinion. It’s a surrender or sharing of authority. But that also makes me realise how seldom The Unfolding Text provides synopses of the stories it mentions, given readers at the time were generally unable to see them again. We must take these authors on trust.

Some of the people interviewed hold pretty sexist views, not least on the role of the Doctor’s companions. This can be very revealing about what made it to the screen. Sometimes the authors also challenge the people interviewed but I think there’s a danger that things said by cast and crew then inform or even dictate the analysis.

For example, producer John Nathan Turner explains how the regular characters in the 1982 series were designed to appeal to a broad audience:

“We’ve got the young heroic Doctor who hopefully appeals to everyone, especially the ladies. We have a female companion called Tegan, who is 24, nice figure, nice legs who appeals to the men. And we have two young companions, Adric and Nyssa, who are both 18-19 and are there for audience identification — the younger audience.” (p. 207)

This is very different to what he inherited a year before from Douglas Adams and producer Graham Williams. Indeed, Nathan Turner thought that the mature, knowledgeable line-up of the Fourth Doctor, Romana and K-9 was “ludicrous”.

“There was no reason for the Doctor ever to have to explain anything to Romana. So that all conversation between them either became very bitchy to impart the plot, or else it was an unreasonable scene where the Doctor has to say, ‘Well, there’s part of your education that you don’t know about, and here it is…’” (p. 217)

When, exactly, is Romana “bitchy”? With episodes now readily available, we can go look for ourselves. Without them, we can only go on Nathan Turner’s say-so.

To be fair, the authors dig into these claims a bit, citing his “nice figure, nice legs” comment twice on the same page before asking him if there had been only tokenistic development of female companions.

“I don’t think it’s tokenism. Certainly the feminists would like Tegan. It just makes for greater drama between your regulars if you’ve got an aggressive girl who tends to think she knows best. It’s not tokenism in any way. It just makes for a better line-up if there is friction.” (p. 218)

But that doesn’t really square with what he said before, which the authors don't really address. Worse, I think, is that The Unfolding Text pursues a line of analysis directed by what they’ve been told and the terminology used.

“In … his second season, Nathan-Turner also reintroduced the 1963 element of Doctor and companions who don’t always ‘get on with one another’ but — very consciously — for ‘character’ rather than ‘bitchy’ reasons. … As with Barbara and Ian [in the 1960s], Tegan’s ‘bitching’ relationship with the Doctor was generated by his inability to return her [home].” (p. 217)

Even in quotations, it’s deploying “bitchy” as objective rather than objectionable. Do Barbara and Ian have a “bitching” relationship with the Doctor? How does the “friction” generated by “aggressive” Tegan differ from the “bitchy” Romana? Is that really the word to use? Go watch those episodes again and I think the answers are no, no and no.

Thursday, May 02, 2024

Doctor Who Magazine - 50 Years of the Fourth Doctor

There are new interviews including Richard Unwin's chat with Louise Jameson and Matthew Waterhouse, Robbie Dunlop's chat with Janet Ellis and Graham Kibble-White's chat with Dave Gibbons. Robbie also met with June Hudson, the costume designer of the burgundy version of the Fourth Doctor's costume seen in his final year in the programme, and with Mark Barton Hill who now owns that coat. How lovely to see a photo of the label, with Tom Baker's name written in under the address of Morris Angel & Son Ltd, the costume house Hudson employed to cut the coat.

It's prompted me to post on the Koquillion site the article I wrote about the Fourth Doctor's Season 18 costume and my chat with Ron Davies who cut the coat.

I've also got two pieces in the new special edition:

pp. 22-25 The Doctor Who Wasn't

A very different version of the Fourth Doctor can be glimpsed in surviving draft scripts and other evidence.

p. 82 Many Happy Returns

He left our screens after 1981's Logopolis - or did he? The Fourth Doctor was never far away.

Wednesday, May 01, 2024

Refracted Lives - Bernice Summerfield fanzine

Thursday, April 25, 2024

Doctor Who Magazine #603

I've written the preview of Episode 1, Space Babies (pp. 14-15), and spoke to writer and executive producer Russell T Davies about this completely nuts story (to quote the preview), ahead of a post-broadcast set report next issue.

I've also written Who Crew: Second Brain (pp. 36-37), in which I spoke to Sharon King and Jess Gardner, co-producers on next year's series of Doctor Who.

Then there's Script to Screen: Jimbo (pp. 38-41), featuring some of the team behind the chonky robot seen in last year's Wild Blue Yonder: production designer Phil Sims, concept artist Nandor Moldovan, prop modeller head of department Barry Jones, and puppeteers Brian Fisher and Eliot Gibbins.

Saturday, April 20, 2024

Blood Legacy, by Alex Renton

Even more incredible is what the author can then tell us about Thompson/Caesar, who escaped enslavement in Jamaica and reached the UK to make his claim in person — and having done so, then agreed to return.

“It seems extraordinary that Sir Adam [Fergusson, Charles’s brother] succeeded in persuading Augustus Thompson to return to Jamaica, despite all the dangers that awaited him. Extraordinary, too, that Thompson trusted him. You have to conclude from the lure that took the runaway back, protected only by a letter from the Fergusson brothers asking that their manager forgive him, was his wife, his mother and his children. Rozelle [in Jamaica] was home.” (p. 140).

We then follow what happens next, though the surviving archive isn’t clear. By late 1785, Augustus Thompson is in hiding. In January 1786, Sir Adam gives permission for Thompson, if he can be found, to be ‘shipped off’ to another island. It’s the last reference to Thompson we can be certain of; there are then scant records listing men that might be him — none of the details are good.

On the whole, though, this is a history of those who profited from slavery, because it is the owners whose records have survived. Their own evidence is damning. And the point is not that a few landowners got very rich but that everyone involved in the supply chain saw financial benefits, down to those who provided food for the crews on the slave ships. As the author admits, this volume tends to crowd out the voices of those who suffered enslavement.

Where those voices can be included, they are. I was really struck, in the last chapter of the book, when the author attends a press conference at the Centre for Reparations Research announcing new data on the involvement in slavery by different European nations. This is more than just about numbers. The database also lists 94,191 examples of enslaved people’s real, African names.

“Most enslaved Africans lost their birth names, and for 300 years there were no original African names in the slave records at all. You might well argue that the lack of names and places of origin, of the things that give us our identity, helped dehumanise the victims of the trade. It has made it easier to them into statistics. … So these original names are to be treasured.”

He quotes Professor Verene Shepherd, slowly reading out a sample of these names at a memorial service.

“Ekhusumee, a girl, aged two, Maloah, a girl, aged two. Captured from Lagos, both of them. Kangah, a girl aged five, captured from Lagos. Peekah, a girl aged four, captured from Lagos. Coulta, a girl aged three, captured from Lagos. Torquah, a girl aged six from Bonny. Ajameh, aged one, a boy, captured from Lagos. Asemah, a boy, aged one, from Porto Novo…” (p. 322)

In an appendix, the author asks what to do now, in light of this horrific legacy. There are more links and information on the Blood Legacy website. And that’s given me more food for thought...

My great-great-great grandfather William Dutton Turner is listed in the Legacies of British Slavery database. When the British government passed the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 to end the trade in the British Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape, they did so on the condition that the taxpayer would compensate slave owners for loss of property. Some 46,000 claimants received a total of £20 million — about £17 billion today. The Treasury was still paying off the debt until 2015 (all details from p. 250).

Blood Legacy suggests that much of this compensation went to pay off recipients’ mounting debts. Turner was awarded about £5,000, and his siblings and other family members also received money. Turner’s third wife, Mary Power Trench (1815-62) — mother of 12 children including James Trench Turner (1840-92)*, my grandfather’s grandfather — was awarded just over £100 in her own right. Yet, when Turner died on 30 June 1858, he left effects valued at less than £20.

Where did the money go? It clearly didn’t stay in the Caribbean, invested in a new future. Instead, it seems to have largely ended up back in the UK, spurring growth and building on an unprecedented scale.

* James Trench Turner joined the army, served in India and was one of the members of the Hong Kong cricket team who died in the sinking of the SS Bokhara. His grandson, born in Guangzhou (Grandpa knew it as Canton) on 14 January 1914, was a guest at my wedding 20 years ago last week.

Thursday, April 18, 2024

The Haunted Tea Set and Other Stories, by Sarah Jackson

Most of the stories in this collection are very short, some just a paragraph, most just two or three pages, and yet they're packed with vivid, evocative strangeness. There are eerie hauntings, there are ordinary witches going about their lives, and more than one story involves someone returning to the community where they grew up where all is not quite right. The strangeness is grounded in well observed, concisely depicted reality, so tangible and effective.

Opening story "Greenkeeper" felt like traditional horror of the sort I'd seen many times before until, after just two-and-a-half pages, it offered a killer last line. "The Haunted Tea Set" follows, and by then I was hooked. That story, and "Subsidence" later on, offer something extraordinary - not just a sense of the ordinary horrors we live with, but the promise of hope and healing.

Sarah Jackson also edits the quarterly short story zine Inner Worlds.

Wednesday, April 17, 2024

The Death of Consensus, by Phil Tinline

The wheeze of the book is that Britain has had mass democracy for just about 100 years, in which it has "lurched from crisis to crisis", with decisions and ideology shaped by what people most feared. Tinline explores these nightmares in three weighty instalments: 1931-45 (fascism, bombing, mass-unemployment), 1968-85 (hyperinflation, military coups, communist dictatorship) and 2008-2022 (the crash, Brexit and lockdown).

As well as digging into the history of each period, each section illuminates the next. For example there's p. 268, when in the early 2010s the Conservatives identify ways to win votes in the traditionally Labour-voting north of England. Here we understand from having read the previous section why the mooted "northern powerhouse" fell short of offering an actual industrial strategy: those involved had personal memories of such things falling flat in the 70s. That in turn illuminates recent claims that one party or other will return us to the 1970s, the nightmares still haunting today's political imagination. It's more that supplying the context; you feel the visceral fear.

This is just one of a number of fascinating connections. Tinline also has an eye for telling detail. Not only does he show how the stage play Love on the Dole made vivid the plight of unemployment in the 1930s, but he spots a great example of the disconnect from those in money and power. Having toured the north to great acclaim, the play finally opened at the Garrick Theatre in London on 30 January 1935, but in the programme,

"Opposite a list of the play's settings--'The Hardcastle's kitchen', 'An Alley'--is a full-page ad boasting that the Triumph-Gloria has won the Monte Carlo Rally (Light Car Class)." (p. 51)

I was also taken by the description of Naomi Mitchison's River Court House on "a short, quiet street right next to the Thames, closed to vehicles at both ends" in Hammersmith. Here, guests coming for drinks and to forge a bold new future included Aneurin Bevan, Jennie Lee, Ellen Wilkinson, Douglas and Margaret Cole, William Mellor, Barbara Betts (later Castle), Michael Foot, EM Forster and WH Auden.

"No ideological cul-de-sac was ever so elegant." (p. 55)

Or there's the vivid portraits of key figures in this densely populated story, such as,

"George Lansbury, the mutton-chopped-whiskered Cockney pacifist, who had long served as the Labour Party's righteous grandpa" (p. 36).

This deft kind of writing enlivens what could otherwise be a dense subject; a political history that is fun.

Though familiar with much of the thesis, a lot of the context provided and the details of politics were new to me. There were other things, too. For example, in the mid 1970s,

"To write her early, hardline foreign policy speeches, Thatcher recruited the historian Robert Conquest, a former communist who, in 1944, had witnessed Stalinists promise to uphold Bulgarian democracy, only to destroy it." (p. 201)

I already knew Conquest's name, but as editor (with Kingsley Amis) of the science-fiction anthologies Spectrum, once a staple of second-hand book shops and a formative influence. In them, I first read Heinlein's "By His Bootstraps" and Clarke's "The Sentinel", two among so many gems that seemed mad and wild and free. It's strange to look back at the contents of those anthologies now and realise they're on the more conservative side of SF. This book about political nightmares has made me think about the blinkers on dreams.

It's strange, too, to see a reference to the event held in Manchester in June 1968 to mark the centenary of the TUC, in which,

"The Prime Minister [Harold Wilson] joined 100,000 trade unionists for a day of celebrations including a parade, a carnival, brass bands, a male voice choir, primary-school dancers from the Lancashire coalfield, fireworks and a pageant." (p. 149)

Only recently, I was digging through the original paperwork related to this event held in the archives of the Writers' Guild of Great Britain. As chair of the guild at the time, former Doctor Who story editor David Whitaker recommended former Doctor Who producer John Wiles as a writer for the pageant. When that didn't work out, Whitaker met with the TUC's Vic Feather (who features a lot in Tinline's book) with Doctor Who writer Mac Hulke, who then produced an outline for the pageant with former Doctor Who story editor Gerry Davis. When the TUC didn't like this and decided to press on without the involvement of the Doctor Who cavalcade, Hulke insisted on still being paid in full - for a script he'd not even written. And he was, after years of disgruntled back and forth. See my book for the whole story.

Anyway. The Death of Consensus is an insightful, enjoyable history that helps to make sense of where we are now. In fact, published in 2022, it finishes on something of a cliffhanger, with Boris Johnson still Prime Minister. I'd be interested to know what Tinline has made of events since publication. We're still caught up in a nightmare but is it quite the same one?