In the 1964

Doctor Who episode

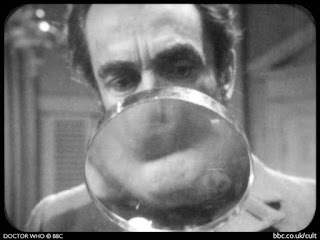

World's End, the TARDIS materialises on the banks of the Thames – but something is very wrong. A sign warns that, under emergency regulations, it is forbidden to dump bodies into the river.

The Doctor's companions also point out what to them is the odd sight of

Battersea Power Station without two of its chimneys (as, er, it is today). All the bustle and business of London, that great centre of trade, has been silenced.

As the Doctor and his friend Ian explore, they discover a clue to what's happening in a desk in a warehouse:

DOCTOR: Ah, here, look. At least we know the century, dear boy. Look.

IAN: 2164.

Now, this calendar is a simple method of telling the audience that we're some 200 years in the future. But I think it also suggests something about the mechanics of the world we've arrived in, as I'll explain in a moment.

Soon the Doctor and his friends discover that Earth has been conquered by Daleks - this is the first episode of a story better known as

The Dalek Invasion of Earth. In the next episode we learn from a man called Craddock how this conquest came about, his speech full of vivid, horrific detail too expensive to realise onscreen:

CRADDOCK: Meteorites came first. The Earth was bombarded with them about 10 years ago. A cosmic storm, the scientists called it. The meteorites stopped, everything settled down - and then people began to die of this new kind of plague ... The Daleks were up in the sky just waiting for Earth to get weaker. Whole continents of people were wiped out. Asia, Africa, South America. They used to say the Earth had a smell of death about it.

Another man, David Campbell, continues the story:

DAVID: The plague had split the world into tiny little communities, too far apart to combine and fight, and too small individually to stand any chance against invasion ... About six months after the meteorite fall, that's when the saucers landed. Cities were razed to the ground, others were simply occupied. Anyone who resisted was destroyed. Some people were captured and were turned into Robomen, the slaves of the Daleks. They caught other human beings and many of them were shipped to the vast mining areas. No one escapes. The Robomen see to that.

The Earth and all its surviving people have become resources for some merciless Dalek project. So what about that calendar? Does it seem likely that after the plague, the invasion and the enslavement of the human race, people continued to print and publish calendars? Or does it seem credible that the Daleks produce them for their human slaves, using our Arabic numerals rather than the Dalek lettering seen elsewhere in the story?

If not, then it seems probable that the calendar was produced before the coming of the meteorites in 2163 (to serve the following year). The TARDIS has landed, according to Craddock, "about 10 years" later so

The Dalek Invasion of Earth is set c. 2173 (23 years after the

movie-version, Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 AD.)

Except that in the 1965 episode

Day of Armageddon, (part of the story known as

The Daleks' Master Plan) the Daleks again threaten Earth, this time in the year 4000. The Doctor refers back to the earlier invasion:

DOCTOR: If the Daleks were going to attack Earth, as you seem to fear, then you must tell Earth to look back in the history of the year 2157 ... History will show how to deal with them.

It's a passing reference. We don't know if 2157 is the date of the meteorites, the plague or the arrival of the Daleks on Earth - or of all three. And perhaps the Doctor has muddled his dates. But if we take him at his word, the invasion of Earth began six years before the production of that calendar.

Now, we could see that as a small continuity error, and conclude that writer Terry Nation or someone on the production team misremembered details of the earlier story. But I prefer to find ways to rationalise such apparent discrepancies - partly )but not only) because I spend a lot of time writing new stories to fit around old episodes of

Doctor Who.

(

Masters of Earth, the very good new story apparently set a year before the events of

The Dalek Invasion of Earth seems to ignore the date given in

Day of Armageddon, using the calendar to conclude that the TV story takes place in 2164, and, following Craddock's "about 10 years ago", that the invasion began in 2153.)

As well as establishing a date, I think we can use the calendar to better understand how the Daleks run their occupation of Earth. Despite enslaving Earth and turning various humans into Robomen, the calendar being produced during the conquest suggests that other humans have at least been granted a level of autonomy to carry out specific tasks set by their Dalek masters. My reasoning is that to complete those tasks successfully requires a certain level of administrative infrastructure, and continuing to print and distribute calendars helps the enslaved humans deliver their tasks on schedule.

The only alternative I can think of is that the calendar has been produced by the human resistance - the allies of Craddock and David Campbell. Perhaps it's useful when planning anti-Dalek activities. But then there's the Doctor's response when he first walks into the warehouse:

DOCTOR: A musty smell. This place hasn't been used in years.

That suggests the warehouse is not in active use by either the Daleks or the human resistance - which is why it's a convenient place to hide a murdered Roboman. But that also suggests the calendar found in the drawer there is a few years' old - so the TARDIS has arrived sometime after 2164. If the Doctor is right in

Day of Armageddon about the invasion beginning in 2157, then Craddock's "about 10 years ago" suggests this is c. 2167, and the warehouse has been abandoned for about three years. But it was still being used six years into the invasion.

For the sake of argument, let's say the calendar was produced by the Daleks and the warehouse, before it was abandoned, was used by the Daleks, too (I'll come back with some corroborrating evidence for that in a bit). The warehouse doesn't seem directly connected to the Daleks' mining project in Bedford - a key part of the plot of the story - so it seems there were other Dalek initiatives going on, which needed warehouses and schedules. There are plenty of other things the Daleks might find useful to exploit from Earth: minerals, or information, or perhaps human slaves they could ship out to work on other Dalek worlds.

That speculation about this particular story is backed up by what happens in 1972 story

Day of the Daleks, when the Daleks have again conquered Earth in the 21st century. Note, it's not the

same invasion as last time, for all it might take place in the same period of future history. In episode 4, the Daleks' human Controller explains to the Doctor and his friend Jo what happened:

CONTROLLER: Towards the end of the 20th century, a series of wars broke out. There was a hundred years of nothing but killing, destruction. Seven-eighths of the world's population was wiped out. The rest were living in holes in the ground, starving, reduced to the level of animals.

JO: So the Daleks saw their opportunity and took over.

CONTROLLER: There was no power on Earth to stop them.

DOCTOR: So they've turned the Earth into a giant factory, with all the wealth and minerals looted and taken to [Dalek planet] Skaro.

CONTROLLER: Exactly. Men who were strong enough, of course, were sent down the mines, the rest work in factories.

JO: Why? Why are they doing all this?

CONTROLLER: They need a constant flow of raw materials. Their empire is expanding.

For all the parallels with the earlier story, we don't see any Robomen in this Dalek-conquered Earth. Instead, the human Controller and his staff of technicians and guards collaborate with the Dalek regime - the Doctor calls the Controller a "

Quisling". In fact, we seen this sort of collaboration in

The Dalek Invasion of Earth when the Doctor's friend Barbara meets a woman and girl who appear to be free:

WOMAN: We make clothes for the slave workers. We're more use to them [the Daleks] doing that than we would be in the mine.

The woman and girl soon betray Barbara to the Daleks in exchange for a small amount of food. To survive, these humans conspire in their own oppression.

There's another clue to the way the Daleks run the planets they conquer in

Death to the Daleks (1974). Here, we learn of a disease wreaking havoc across various worlds. But this is a not a Dalek plot, a prelude to yet more invasion. As the Doctor explains in episode 2:

DOCTOR:

Several of the planets the Daleks have colonised are suffering from the

same disease. They're dying in millions. Now they need that chemical

just as badly as you [humans] do.

His choice of words is interesting - he refers to planets the Daleks have "colonised" not conquered, which (for all

Doctor Who of the period critiques colonies in space) almost sounds like he thinks they're there legitimately. More pertinently, the Daleks have been prompted to act because people are "dying in their millions". Why would the merciless Daleks care about that? I think the only reason can be that the Daleks

need these people to make their empire work. They may talk about wanting to exterminate all other life forms, but in the short-term they must be more pragmatic. They need us.

(ETA: Jonathan Morris points out that later in the story the Daleks say that, having gathered up all the supplies of this special chemical, they "can force the space powers to accede to our demands. If they do not, millions of people on the outer planets will perish." But if the Daleks have, as the Doctor says, colonised worlds with millions of people, that potential for blackmail is in addition to that need to cure their own workers.)

(ETA 2:

Paul Smith points out that we're given no indication that these "colonised" worlds of the Daleks were populated by anyone other than Daleks, so that it is Daleks "dying in the millions". That's not how I'd interpreted it, but watching again I think Paul is right. Even so, we know from other examples how the Daleks treat native populations as their exploit a planet's resources: see their invasions of Earth (above), Spiridon (in

Planet of the Daleks (1973) and Exxilon (in

Death to the Daleks (1974).)

The expanding Dalek empire is not only reaching out into space for ever more resources.

Day of the Daleks also suggests something new, as the Doctor is told in episode 4:

DALEK:

The Daleks have discovered the secret of time travel. We have invaded

Earth again. We have changed the pattern of history.

The Daleks had the ability to travel in time in three of their four previous onscreen adventures,

The Chase (1965),

The Daleks' Master Plan (1965-6) and

The Evil of the Daleks (1967).

But note that the Dalek says "again". They're using time travel to

rewrite the events of

The Dalek Invasion of Earth, coming back to conquer the Earth at the same point in

future history, but this time doing it better to more efficiently exploit Earth's resources.

The Doctor defeats this attempt to change future history, and the suggestion at the end of

Day of the Daleks is that he has thwarted the Dalek invasion. Yet in part 1 of

Remembrance of the Daleks (1988), we're told this:

ACE: And now [the Daleks] want to conquer the Earth [in 1963].

DOCTOR: Nothing so mundane. They conquer the Earth in the 22nd century.

So the Doctor prevented the invasion in

Day of the Daleks from ever happening, but not the one from

The Dalek Invasion of Earth - which now takes place as before. There's a clue as to why that might be in part 3 of

Remembrance of the Daleks, when the Doctor warns Ace about changing history:

DOCTOR: Ace, the Daleks have a mothership up there capable of eradicating this planet from space, but even they, ruthless though they are, would think twice before making such a radical alteration to the time line.

Note that it's not that they wouldn't do it, just that they'd think twice. Why?

As we've seen, the Dalek empire depends on expansion to gain ever more resources, and the gathering of those resources depends on the work of enslaved people. The most efficient use of these people is not merely to enslave them, robotised or otherwise, but to offer some of them autonomy to run particular tasks themselves, with an infrastructure to support them which includes printing calendars. But all of this takes ever more resources, so the Dalek empire must constantly expand. And that brings them up against a people just as powerful as they are.

TIME LORD: We foresee a time when they will have destroyed all other lifeforms and become the dominant creature in the universe.

In

Genesis of the Daleks (1975), the Time Lords send the Doctor back in time to the point where the Daleks were created. He is meant to either destroy the Daleks entirely, or affect their creation so that they will develop to be less aggressive. It's effectively what the Daleks do in

Day of the Daleks - using time travel to pre-emptively weaken a rival.

It's been argued that

Genesis of the Daleks sees the Time Lords strike the first blow in what will become the devastating Time War between them and the Daleks, which has haunted all of

Doctor Who since 2005.

But we don't hear of the Time Lords battling the Daleks again until the events of the Time War. Indeed, Davros - creator and later emperor of the Daleks - tells the Doctor in

Resurrection of the Daleks (1984):

DAVROS: You are soft, like all Time Lords. You prefer to stand and watch. Action requires courage, something you lack.

The suggestion is that, despite provocation, the Time Lords are not acting against the Daleks - yet Davros is still plotting to wage war on them. Then, in

Remebrance of the Daleks, the Daleks battle for control of a remote stellar manipulator that will give them the same power over time as the Time Lords.

I noted before the Doctor's comments in this story that the Daleks would be wary of making big changes to history. We've seen them change (future) history before, so perhaps the wariness is because they know they lack the same powers over time as the as the Time Lords, who would thwart such interference (just as the Doctor, a Time Lord, does in

Day of the Daleks).

So my thesis is that the Daleks cannot expand their empire through history while the Time Lords have superior power over time. But the Daleks must expand their empire through history because of the way that empire operates, guzzling up ever more resources.

And we can trace how it operates - and thus the economic root of the Time War - from that calendar found in

World's End.

(I'm thinking through this kind of stuff as I work on my book about

The Evil of the Daleks (1967), to be published by the

Black Archive next May. So expect more. Sorry.)

"Dancing at the end of time," proclaims the newly released cover for Graceless IV, the artwork by Anthony Lamb.

"Dancing at the end of time," proclaims the newly released cover for Graceless IV, the artwork by Anthony Lamb.