|

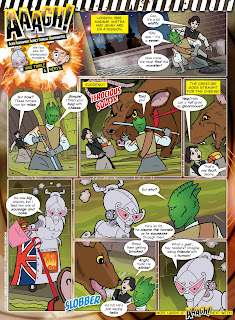

| AAAGH! Steampunk Mrs Tinkle |

Thursday, May 31, 2012

AAAGH! Steampunk Mrs Tinkle

Sunday, May 06, 2012

What they thought, felt and said

Generally, it’s excellent, such as when detailing Wells’ argument with the Fabians – here a bunch of well-meaning middle-class liberals who want to bring about socialism in Britain, but not so soon as to affect their own cosy standard of living. Wells is much more impatient to bring about social revolution and welfare, what with the practical experience of his youth.

“It wasn’t real poverty. We never starved, but we had a poor diet, which stunted my growth, and made me susceptible to illness. We never went barefoot – but we wore ill-fitting boots and shoes. It was a kind of genteel poverty. I was never allowed to bring my friends home to play because they would see that we couldn't afford a servant, not even the humblest skivvy, and word would get around the neighbourhood. My parents scrimped and saved so they could send me to the cheapest kind of private school, and avoid the shame of a board school, where I might have had better-trained teachers.”It’s a revealing portrait of a lower middle-class existence, all too aware of and aspiring towards a better social standing. But the real skill is in how this description echoes later. Without making a direct link to this earlier passage, Lodge describes Wells – as an established author – wooing the socialist Fabian Society with his essay, The Misery of Boots (1908). There, he uses a working man's ill-fitting boots – the pain and discomfort caused, the effect on the man's posture – to show how poverty defines a person's outlook and ambition, going on to deplore the preventable misery of social injustice and call for the end of private property.

David Lodge, A Man of Parts, p. 45.

Later still, the dying Wells concludes that the Labour party of 1945 is a creation of these same Fabians, still – despite their campaign for a welfare state – in no rush to deprive themselves of comfort. Even if that was what Wells thought at the time, it sits oddly given that the Labour government brought in such radical social change and nationalisation in the post-war years. They did the things Wells complains they will not do.

I suspect that Wells' remarks are aimed less at his own time as the (New) Labour party of today. Lodge is keen to underline Wells' continuing relevance to us, and the book ends with a rather clumsy metaphor about this common man prophet. On learning of Wells' death, Rebecca West remarks (through Lodge) that Wells was not a meteor who burned brightly once but a comet in a long orbit, whose time will come again.

There's plenty of evidence that Wells was ahead of his time. He lived to see the reality of things he predicted decades before – aerial bombardment of cities and the atomic bomb. But the book credits him with more than he can really have claim to, such as in this clunky bit of wordplay:

“I imagined an international Encyclopaedia Organisation that would store and continuously update every item of verifiable human knowledge on microfilm and make it universally available – a world wide web of information.”

Ibid., p. 485.That’s not really a web so much as a centrally controlled giant library. And that word “verifiable” doesn’t exactly describe much of the internet as we know it. I’m wary, anyway, of a writer's worth being judged by how much he guessed correctly. Wells also dreamt up a time-travelling bicycle and invaders from Mars, and those novels are no poorer because they did not happen in reality.

For a writer of books ‘of ideas’, Wells’ story is full of human drama which Lodge has mined for psychological detail. We really get under Wells' skin. One highlight is when Wells – himself causing a stir for promoting and living ‘free love’ – discovers that the pious, conservative Hubert Bland (husband of children's author E Nesbit) who opposes him is a serial womaniser whose household includes two children born out of wedlock to his maid. We, too, have come to love the Nesbits and their home, and we, too, feel the vicious betrayal of this hypocrisy.

Yet having followed Wells’ life in detail up to the 1920s, we then rather skip on to the end. The death of his loyal wife Jane is little more than an aside, which is an extraordinary and glaring omission. It's remarked on merely when Wells fears going through his late wife's things and finding evidence that she have had a lover of her own. That's especially strange given how much she's supported him – in his work and his affairs. There's little on what he thought or felt in her final days, or how her illness affected him or made him rethink what he'd done.

Perhaps that would detract from Lodge's sympathetic portrait of Wells, or perhaps Lodge loses interest in Wells once he's peaked as a writer. It seems odd to brush over a decade of the man's life then attempt to sum the whole of him up.

Lodge's Wells is defined by his frustrations – sexual, political and artistic. There's a telling admission in the closing pages:

“I was outwardly successful – ‘the most famous writer in the world’ – but inwardly dissatisfied. The praise I got was not the kind I wanted or from people I wanted to get it from. It made me arrogant and irritable – I was aware of that, but I couldn’t control myself at times.”

Ibid., p. 499.But I think the most telling statement is Lodge's own, before the novel begins:

“Nearly everything that happens in this narrative is based on factual sources – 'based on' in the elastic sense that includes 'inferable from' and 'consistent with'. All the characters are portrayals of real people, and the relationships between them were as described in these pages. Quotations from their books and other publications, speeches, and (with very few exceptions) letters, are their own words. But I have used a novelist's licence in representing what they thought, felt and said to each other, and I have imagined many circumstantial details which history omitted to record.”

David Lodge, preface to A Man of Parts.There's something deceptive about these words. It's as if what these people thought, felt and said is just a slight embroidery on the solid, historical facts. But invented motives don't just frame what happened, they shape our whole perception of the man and his world. This is not simply a literary biography but a novel with Wells a character of Lodge's own invention, thinking and feeling what Lodge wants him to feel.

The book is a fascinating, compelling story full of great anecdotes and insights. But I couldn't shake the sense that it's more about Lodge than it is Wells.

Tuesday, December 06, 2011

Hundred year-old cat

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

John

I loved the brooding power of John's portraits when I first saw them during my A-levels, then discovered the artist lurking in old photos of the Fitzroy Tavern (John first met Dylan Thomas there, says the book). I'd seen the book a few times in remainders and second-hand shops, but been scared off by the size and its strikingly ugly cover.

But John's name and work has continued to crop up in other things I've been reading, and when I was in Cardiff in March, his portrait of Mavis Wheeler at the National Museum Wales was the one that held me transfixed. In a few, simple lines – seemingly dashed off – he conveyed not just a beautiful woman but a tantalising sense of her character: thrilling, smart and naughty.

Mavis was wife of another hero of mine, the twinkly archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler. So I thumbed through the book to see if Mortimer got a mention. And bought the book on the basis of this single line:

“Wheeler, Sir Mortimer: challenged to a duel by AJ, 526-7”

Index to Michael Holroyd, Augustus John – The New Biography, p. 717.Holroyd tells John's life broadly in chronological order, from his days in fear of a strict father in Tenby, through art school rebellion into established notoriety – as much for his private life as his work. John was fascinated by the gypsy life, learning their language, living among them, wearing big hoop ear-rings. And there's a constant wanderlust in the book; in his last few years he seems especially fidgety because he can't just climb into a young woman's bed or disappear off across the country. There’s the striking image of him, a month before he died, frail and ill, but taking part in an anti-bomb sit-in in Trafalgar Square.

John's the archetype of a particular kind of artist: a beardie, boozy, bombastic womaniser, father of too many children to keep track of, constantly getting into rages and fights. He's not a particularly likeable man – he treats his wife Ida particularly badly – but Holroyd mines his antics for detail, insight and comedy. There's a particular gem of rascally, drunk lechery on pages 289-91 that’s got the feel of Withnail. John sneaks round a friend's house at night in search of his two pretty “secretaries”, gets the wrong room and ends up in the nursery with the governess (a dwarf). In the scandal the next morning, he leaves in disgrace but is pursued by the friend who John takes to the pub to set things right, where they get into a boxing match with a complete stranger. As Holroyd says, the stories about John are much more fun to read than be a part of.

For all his unconventional ways, John mixed with key figures of the period, painting their portraits, getting them drunk and – if they were women – fucking them. Ian Fleming's mum, the wives of both Mortimer Wheeler and Dylan Thomas, his own son's girlfriends (and possibly, their wives) and any number of models are included in the list. This sexual appetite is mixed up with anecdotes about his friendships with Hardy, Bertrand Russell, Lawrence of Arabia, Prime Minister Asquith and the Queen.

The book is often engrossing because of other people's lives – John's wife Ida, his sort-of wife Dorelia and sister Gwen are as much part of the story. But even the smaller roles are vivid. Take the subject of the portrait that made me buy the book. Mavis – really Mabel – Wright had an affair with John before she married Mortimer Wheeler. And it looks like they overlapped long afterwards, too. The first mention of her reminded me of Sarah, Pauline Collins' character in the first series of Upstairs, Downstairs:

“About her background she was secretive, confiding only that her mother had been a child stolen by gypsies. In later years she varied this story to the extent of denying, in a manner challenging disbelief, that she was John's daughter by a gypsy. In fact she was the daughter of a grocer's assistant and had been at the age of sixteen a scullery maid. During the General Strike in 1926, she hitchhiked to London, clutching a golf club, and took a post as nursery governess to the children of a clergyman in Wimbledon. A year later she was a waitress at Veeraswamy's, the pioneer Indian restaurant in Swallow Street”.

Ibid., p. 524.Holroyd uses these relationships to cast light on John's own work. But I found there was generally little analysis of John the painter. The book reproduces only a handful of his works and though we're told of fashions and fights in the art world, I didn't ever feel the book explained or grouped his work. His portraits are discussed in terms of how much they looked like or pleased the sitter:

“Men he was tempted to caricature, women to sentimentalize. For this reason, as the examples of Gerald du Maurier and Tallulah Bankhead suggest, his good portraits of men were less acceptable to their sitters than his weaker pictures of women.”

Ibid., p 469.There's even less on the style or composition of his landscapes, and his still life work is almost dismissed out of hand. We’re told he only tried clay late in life.

John’s frustration with his own work is evident – a late anecdote has the old man crying in the street at his own lack of ability. Holroyd details him prevaricating for years over particular portraits, or painting over or destroying work he alone seemed not to like. Despite saying that he didn’t fulfil his potential, Holroyd tells us that John worked hard and continually – the cruel irony being that work wasn’t necessarily improved in proportion to the hours devoted.

I'd have liked more on the traditions he worked with in, the tools he used, the kind of brushwork and marks on the canvas. Holroyd seems to agree with critics who claim (and did so at the time) that John never quite realised the promise of his early work, but doesn't venture an opinion on why or what he should have done.

It's a rich and rewarding biography of the man but not the artist.

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Francis Galton and eugenics

Galton, who invented the term eugenics and liked his statistics, also sported a fine pair of sideburns which are still the fashion. The Dr's worked on exhibitions and things to mark the centenary of his death.

Monday, May 31, 2010

Books finished, May 2010

I've already blogged about Doctor No. I reread The Mythological Dimensions of Doctor Who - for which I wrote a foreword - in advance of being on a panel at the launch last week. (I've also skimmed through a PDF of Daddy's Girl by Deborah Watling, in advance of interviewing her a fortnight ago at Utopia.)

Roald Dahl is keen to explain upfront that Boy is "not an autobiography", but rather a series of vivid memories that made an impression on him. This first volume sees him up to leaving school, and is full of the kind of hi-jinks we'd expect from his fictional stories. There are beastly teachers and grown-ups, outrageous (and cruel) pranks like putting a dead mouse in a jar of sweets or making his brother-in-law smoke a pipe of poo.

The book is aided by extracts from Dahl's own letters, meticulously kept by his mother. We get glimpses of the rather serious child, struggling with spelling and the expectations of his posh school. There are plenty of insights into corporal punishment and the etiquette of the tuck box.

It's a fun, engaging read but there's little to suggest Dahl has particularly re-examined these scenes. There's little reappraisal or apology, so that though we learn a lot about the early life of the author, there's no sense that, in writing this, he has.

Going Solo - which I'd not read before - is an altogether more adult book, and I think would have shocked me as a child. Dahl joins Shell and is posted out to Africa, where he lives a rather comfy existence with servants (or "boys" - he doesn't notice the irony of his own nickname) before the outbreak of war.

The episodes are a lot more vicious than the innocence of Boy, with a man being shot in the face right in front of him and his servant murdering a German. As always, Dahl is good on vivid detail, and the book is again littered with extracts from his original letters and also from his log book.

There's a lot on Dahl the pilot, flying in the 1941 Battle of Athens and barely surviving a crash in Egypt. Writing decades after the events, he's still furious about the poor management of the air force and the ghastly waste of lives. Characters are introduced quickly and are then abruptly shot down. While Dahl never shies away from telling us he was a brilliant flyer, he also admits repeatedly that he only got through it by luck.

The book ends with Dahl sent back to England in the summer of 1941, the persistent headaches following his crash invaliding him out of service. It's frustrating to leave it there with so much more still to tell, and I assume there'd have been at least a third volume if Dahl had only lived. With a birthday looming I've set the Dr to find me a good biography so I can find out what happened next (and how much of the story Dahl's already told me can be considered true).

"The achievements of great men always escape final assessment. Succeeding generations feel bound to reinterpret their work. For the Victorians, Morris was above all a poet. For many today he is a forerunner of contemporary design. Tomorrow may remember him best as a social and moral critic of capitalism and a pioneer of a society of equality."Shankland's introduction to a short supplement on Morris the designer underlines the emphasis of this odd collection. The first 180 pages comprise letters, lectures and reflections in which Morris puts forward socialist ideas, plus some pretty uninspiring poetry and hymns with which to entertain the workers. Though the sentiments are noble, there's little of great wit or insight, and I couldn't help feeling I'd read this kind of thing better put by other people.Graeme Shankland, "William Morris - Designer", in News From Nowhere and Selected Writings And Designs (ed. Asa Briggs).

Shankland's short supplement addresses the extraordinary design work, with 24 photographic plates that, being in black and white, don't quite show the sumptuous richness of the man's achievements. Vibrant and heavy, Morris's stuff is from an age of large rooms with high ceilings before the anti-chintz mandate of Ikea. Even in their own time they were retro, harking back to a pre-industrial, hand-crafted age.

Being so woefully impractical myself, I view Morris with considerable envy. (The Dr is also a great fan, so I live with a fair bit of his wallpaper.) He willfully embraces a romantic myth of England's past in his subjects, and believes in good and practical design. His infamous quotation to "have nothing in your home that is neither beautiful nor useful” is a rejection of Victorian tat and ornament but is all the more relevant in our jostling flats and apartments. Ikea might have extolled us to chuck out the chintz, but it's elegant, uncluttered and socialist use of space is not a million miles from his.

The main meat of the book, though, is a maddeningly abridged News From Nowhere, the science-fiction tract about a man from 1890 popping to the 21st Century. It's largely a chance to explore a sunshiney, communist idyll, where dustmen wear gold clothes, the Palace of Westminster is used for storing manure and crime and ugly children no longer exist. There's equality between the sexes and a minimum wage.

It'd difficult reading this idealised parable without comparing it to the practical examples of Communism that existed in the 20th Century. As in Child 44, the dogma that socialism will rid the world of crime merely meant crimes were ignored or brushed under the carpet, and the abuses of the capitalist system were replaced by abuses of different kinds. We keep being told it's like something out of the 14th Century, too, which hardly makes it sound inviting.

There are some fascinating things in Morris' vision, though. London seems comfortably multiracial in this future:

"Within [the shop] were a couple of children - a brown-skinned boy of about twelve, who sat reading a book, and a pretty little girl of about a year older, who was sitting also reading behind the counter; they were obviously brother and sister."(Yes, I appreciate that the boy might just be tanned from lots of time playing outside, but that's not quite how it reads today.)Morris, William, "News From Nowhere And Selected Writings And Designs", p. 212.

There's free love and yet with the propriety of marriage (a young couple have been married, she's then married someone else, and now they're getting back together). People are prettier and seem younger than they would in 1890 as a result of better living conditions (something that turns out to be true).

There are also odd things: quarrels between lovers leading to death is not uncommon in this paradise. They still use whips to drive their horses, and it's weird reading of,

"the natural and necessary pains which the mother must go through [in childbirth, that] form a bond of union between man and woman".Mostly, the book is taken up by a long dialogue between our Victorian traveller and an ancient man who knows his 20th Century history, explaining some of the changes. For all its aping the style of Plato's Republic, this is really a monologue setting out the vision of a cheery future.Ibid., p. 235.

And, then at the end of this lengthy interview, this edition skips to the end:

"[Chapters 19 to 32 describe Morris's journey up the River Thames past Hampton Court and Runnymede, the characters he met and the sights he saw. The book ends with a feast at Kelmscott and his sudden return from utopia to the nineteenth century, from the world of 'joyous, beautiful people' to the 'dirt and rags' of his own time. He ends with these reflections.]"It's like deciding to publish 1984 but only with the excerpts from The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, and none of that boring stuff between Winston and Julia. This edition could easily have included the whole unabridged text, making room for it by excising the selected other writings. You can't hope to convince us of the importance of Morris's utopian vision by such brazen selective quotation.Ibid., p. 300.

Saturday, April 17, 2010

Volcano Day

I escaped the hotel room earlier so the Nice Lady could make the bed and towels all tidy. The Nice Lady warned me to watch out for falling ash and hellfire, as the papers are warning its not good for your health to stand downwind of an explosion.

The hotel reception was packed full of airline cabin crew and other people all hoping desperately for rooms. It's the first sign of the fall-out from Iceland that I've seen (though apparently my brother and his family are also stranded in Crete, having a lovely time.)

Anyway, with the imminent prospect of death, I headed to the cathedral to see the Necropolis, which is apparenltly based on Pere Lachaise in Paris. It's high on a neatly-mowed hill overlooking the city, and suitably bleak and Mad Victorian. It pattered with rain as I nosed about. Other tourists check nervously to see it was only water. But I knew we were being watched over by a guardian angel, parked under the no parking sign just by the Necropolis gate...

(There are also, of course, TARDES parked all over Glasgow. The Dr has taken pictures of me sulking by the fine example on Buchanan Street.)

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Underground movement

It's been closed since 2007 for major refurbishment and opens again in May as part of the Overground network (which runs about 600 yards from my house). I hope it will then be tweeting.

Yesterday was a last chance to walk under the river. This was, of course, magnificently exciting.

Photo by Nimbos. More photos of the tunnel on Facebook for those as fancy.

Sunday, February 21, 2010

Domestic bliss

On Friday, I took a few hours off to go to London Zoo with the Dr. It was 10 years since I'd first stumbled up to her and said "You're lovely." As I said this time last year,

"The lesson is, my young padawans, that if you fancy someone, tell them."

We'd adopted each other animals at London Zoo - I got the Dr an Asian lion, she got me a lady gorilla reputed to stink of garlic. The Asian lions were best, all snuggled up in a pile, watching us visitors languorously. We also liked the baby monkeys and the owls. I took a picture of the Dr playing with the tiger-paw gloves, and realise now we should have bought them.

We'd adopted each other animals at London Zoo - I got the Dr an Asian lion, she got me a lady gorilla reputed to stink of garlic. The Asian lions were best, all snuggled up in a pile, watching us visitors languorously. We also liked the baby monkeys and the owls. I took a picture of the Dr playing with the tiger-paw gloves, and realise now we should have bought them.We were home well in time for the live EastEnders, which was all rather manic and brave. M'colleague Lisa Bowerman says that audio drama separates the men actors from the boys, and the same seems to be true of live telly. Turned over to BBC Three after, to shout at the obscenely indulgent behind-the-scenes thing. Managed about 20 minutes.

Instead we put on another True Blood - we're now five episodes into season 2. It's much stronger than season 1, with more screen-time and plot for the other characters around Sookie and Bill. The Dr loves the comedy vampires. But it is all having an effect on the cat.

Instead we put on another True Blood - we're now five episodes into season 2. It's much stronger than season 1, with more screen-time and plot for the other characters around Sookie and Bill. The Dr loves the comedy vampires. But it is all having an effect on the cat.Yesterday I wrote a comic strip and two (very) short stories, which I hope will be approved by the Masters. Then I went out to see Ghosts, a play by Ibsen reworked by Frank McGuinness, starring Lesley Sharp and Iain Glen. It's a brilliant play about the shadow cast over a family by a long-dead father - who remains a constant presence though never appearing in person. A very deft bit of writing, and Sharp and Harry Treadaway (playing her son) were incredible. Not entirely convinced by some of the accents, though. Glen seemed to be playing the vicar as Abraham Lincoln.

Today, I was interviewed about my Being Human book and am writing more stuff, while the Dr is finishing her William Morris embroidery by attaching it to a cushion. Later we shall eat the kilo of best beef what I bought as a treat.

Today, I was interviewed about my Being Human book and am writing more stuff, while the Dr is finishing her William Morris embroidery by attaching it to a cushion. Later we shall eat the kilo of best beef what I bought as a treat. But perhaps our most exciting news is that we have a bath. It's been five weeks since the shower was pulled apart. B&Q's promise to deliver our purchases "within three weeks" turned out to be not entirely true. Their promise to ring us with a date of delivery, and to let us know why things were delayed, was not entirely true either. The Dr chased and chased - and spoke to some helpful, apologetic people - and the stuff was finally delivered on Thursday. Well, all except the end panel for the bath which we hope will now come next week.

But perhaps our most exciting news is that we have a bath. It's been five weeks since the shower was pulled apart. B&Q's promise to deliver our purchases "within three weeks" turned out to be not entirely true. Their promise to ring us with a date of delivery, and to let us know why things were delayed, was not entirely true either. The Dr chased and chased - and spoke to some helpful, apologetic people - and the stuff was finally delivered on Thursday. Well, all except the end panel for the bath which we hope will now come next week.The delays have meant our helpful Man has taken on other works, but he was round late last night getting it set up so that we can at least have a wash. It stills needs plenty of work, and there's a sink to be put in, but we're both skippy with delight.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Books finished, January 2010

"The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart" by Jesse Bullington

"The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart" by Jesse BullingtonReviewed this for Vector, so I'll blog that later this year. But spectacularly not my cup of tea and I struggled to find anything nice to say. Sorry, Jesse. Amazon's reviewers clearly like it.

"The Story of Parliament in the Palace of Westminster" by John Field

A rather dry, worthy and partisan history of the buildings most people refer to as the "Houses of Parliament" - you can tell Field was a teacher. Some periods in history are lavished in detail, others barely get a mention. For example, Field abruptly jumps from the Second World War to the end of the 20th Century, with a rant about democracy now and our place within it.

Yet there's plenty of fascinating top facts and insights. There's the appalling comedy-of-errors as bureaucracy and petty politics, committees, inquiries and an ever-changing brief hamper the building of Pugin and Barry's new palace in the mid-Nineteenth Century - and killed off both those men. The frescoes of radiant British history famously came out too dark because of the inclement British weather, while the over-large statues of major British figures were quietly moved elsewhere. It leaves you amazed that we ever had an Empire. You can almost believe the old argument that we took Africa and India more by accident than design.

I was also fascinated by subtle changes wrought on the constitution during the brief reign of Edward VI. His dad, remember, had broken off from the Catholic church so as to get a new wife (which is why anyone from the Church of England who speaks against divorce and remarriage should be beheaded for Treason). During Edward's reign (with my emphasis in bold),

"The 1548 Parliament passed the First Act of Uniformity, which introduced an English prayer book, imposed penalties for non-observance, and ordered the suppression of both images and Latin primers. It was the first occasion when religious practice had been proscribed by a secular authority. The Second Act of Uniformity followed in the 1552 Parliament which required every subject to attend church on Sunday, at one of the rechristened services of morning prayer, evening prayer, or the Lord's supper. This Act was the beginning of 'keeping Sunday special'. It was accompanied, appropriately by an Act for the control of alehouses by Justices of the Peace, when liquor began for the first time to be licensed."So "keeping Sunday special" was a specifically anti-Catholic measure, not our version of the Sabbath. It's also worth noting that Edward VI did not so much rule himself as governed through helpful "uncle" figures and Parliament - nearly a century before Oliver Cromwell, let alone the constitutional monarchy of William and Mary.John Field, "The Story of Parliament in the Palace of Westminster", p. 79.

It's packed with stuff like this. Another favourite is in 1842, when the non-parliamentary Royal Fine Arts Commission held a competition for the interior decoration of the new palace, with two notable firsts:

"Cartoons were invited, either of subjects from British history, of of scenes from the works of Spenser, Shakespeare and Milton. The exhibition [of these] was the occasion for Punch to appropriate the word 'cartoon' and apply it for the first time to comic subjects, the magazine's own spoof entries. It was the first time that state patronage had been offered to artists."Field is right that the palace today still feels like a gentleman's club, with arcane rules and traditions deliberately aimed at tripping up the newcomer. He's also good on Lords reform, and the value of individuals of experience and with ostensibly less party allegiance to the scrutiny of Bills. So plenty of valuable research and insight, but the phrasing and grammar could be better, and there are odd concentrations of focus which mean the book loses a few marks.Ibid., p. 191.

"Matilda" by Roald Dahl

"It's a funny thing about mothers and fathers. Even when their own child is the most disgusting little blister you could ever imagine, they still think that he or she is wonderful."I've long meant to remedy the Dr's ignorance of the works of Roald Dahl. This was a perfect place to start, with a small, bespectacled and earnest girl who was reading newspapers at the works of Charles Dickens at the age of five. She was quite enthralled.Roald Dahl, "Matilda", p.1.

It's odd for me reading it again how thrilling and vivid it is, with Dahl simply and elegantly drawing us in to the adventure. It struck not only how black and white his characters are - villains like Matilda's parents and Miss Trunchball are 100 per cent villainous - but that this reflects a child-like view of grown-ups. There's no sense of these adults having once been children themselves - Miss Trunchball denies that very thing - or of their characters and outlooks developing. What, I wondered, went so wrong to turn Miss Trunchball into such a monster?

It also seems of its time, with Dahl sniffy about television and Matilda's dad a brash, conscience-less small businessman, reaping the boon of the Eighties. The plot is about a young girl taking charge of her life and reclaiming a stolen inheritance - just like the Victorian novels that Matilda reads. But it's also about the pernicious greed of its age.

It also seems odd now that Dahl recommends Hemmingway and, "Brighton Rock" to the children readers, and quotes from Dylan Thomas' haunting, "In Country Sleep". And I'm delighted this edition includes writing tips from Dahl, which includes his "constant unholy terror of boring the reader". We're already working our way through more of Dahl, so will blog some more on him soon.

"Family Britain 1951-57" by David Kynaston

I loved "Austerity Britain", which I read last year and singularly failed to blog. This picks up the story, a whopping, fat mash of diary extracts, political journals, news, sport and current affairs, building up an impression of the era. It's utterly compelling and covers such enormous ground. Kynaston's got an eye for details which inform or reflect the worries of our own age - the terror of "coshing" from teenage boys, the fury of the tabloid press, the floods and train disasters and the impact of invading - in this case, Suez - without a UN mandate. The truth is just starting to come out as the book closes, with Prime Minister Eden's explicit lie to the Commons about there having been no secret plot with Israel.

Kynaston's also good at explaining the effect of such moments, such as this quotation from the Daily Mirror on 5 November 1956, explaining why everyone must abide by international law if it's to have any meaning:

"'Once British bombs fell on Egypt the fate of Hungary was sealed,' asserted its leader. 'The last chance of asserting moral pressure on Russia was lost when Eden defied the United Nations over Suez.' Almost certainly Khruschev would have acted as he did anyway, sooner rather than later, but undeniably Suez provide opportune cover."The struggles of the British Communist Party to reconcile themselves to the fate of Budapest - and to revelations about all Stalin had been up to - seem another world, as are the worries about coal fires and rationing, or the assigned roles for men and women. It's the world we live in and another planet - something you can experience with this incredible, haunting slideshow of photographs of the 1950s.

Three choice moments from the book to whet your need to read it: in 1952 in Oxford,

"a thrusting Australian undergraduate had stood for secretary of the University Labour Club and, in defiance of the rule against open canvassing, had campaigned on the slogan, 'Rooting for Rupert'. Complaints were made to the club's chairman, Gerald Kaufman, who initiated a tribunal. The outcome was that young Rupert Murdoch was not allowed to stand for office."That same year, the forthcoming White Paper about ending the BBC's monopoly on television - allowing the creation of ITV - led to "agitated correspondence" in the Times:Ibid., p.102.

"'This is the age of the common man, whose influences towards the deterioration of standards of culture are formidable in all spheres,' warned Lord Brand. 'It is discouraging to find that it is in the Conservative Party which one would have thought would be by tradition the party pledged to maintain such standards, that many members in their desire to end anything like a monopoly, seem ready to support measures which will inevitably degrade them.' Violet Bonham Carter agreed: 'We are often told the B.B.C. should "give the people what they want". But who are "the people"? The people are all the people - including minorities. Broadcasting by the B.B.C. has no aim but good broadcasting. Broadcasting by sponsoring has no other motive but to sell goods."Just as today, hacking flesh from the BBC might let other people make money - some of them Tory grandees - but does it mean any improvement in telly? There's an argument now that ITV has suffered not because it's up against the BBC, but because commerical television can only flourish and not dilute the quality of its material while it has a monopoly, too.Ibid., p. 106.

And though I don't agree with the sentiment, I loved Churchill's masterful analogy for the political divide at the 1955 General Election:

"'Queuetopia remained Churchill's central metaphor for socialism in action - a term designed specifically to appeal to housewives. 'We are for the ladder,' he declared in his election broadcast. 'Let all try their best to climb. They are for the queue. Let each wait in his place till his turn comes.'"In all the book is a window into an age so much like and so different from our own - an expert piece of world-building, to use the science-fiction term. Interspersed with the names of films and performers, brands of cigarette and clothes, sportsmen and commentators and etc., the impression builds into a vivid portrait. It's a place of green smog that stings the throat like pepper and shrouds the stage from an opera-going audience, of "National butter", of the slow, slow end of rationing and the first shifts in public opinion on the medieval laws on homosexuality and on capital punishment. A glorious book and enthralling. I eagerly await the next volume.Ibid., p. 33.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Will scrawl for food

Got plenty of work on, and am working every spare moment, but not all of it's very highly paid. Then there's the projects which get cancelled when I'm already well into them, or the fun discussions after delivery where it turns out the bosses can't pay all that they said.

This sort of thing has gone on since I went freelance back in 2002, but it seems to be happening a lot more in the Current Climate. There seem to be far more people gunning for the jobs, and that can even mean the applications process is all much more complicated so as to ward some of these people off.

But a desperate Tweet earlier this week has paid off rather nicely, and I've spent a busy few days pitching stuff every which way. Got some meetings and things coming up, too, so it's all looking a bit more hopeful.

In the meantime, I had a lovely afternoon at the NFT on Saturday, with Bernard Cribbins on fine form as he entertained a packed cinema mostly full of geeks. I think I must have known half the people there, and got to say "Wotcher" to most of them. Also chastely admired a pretty lady two rows in front, before realising it was Channel 4 News' Samira Ahmed.

On Sunday, the Dr dragged me from the typing to go see Sherlock Holmes. Must admit I dragged my feet a bit - I've avoided Guy Ritchie since Revolver [my review of which has vanished from the Internet; I shall look into that]. But it's a smart, exciting and funny film, packed with glorious details, from the works of Conan-Doyle himself and Victoriana. The House of Lords is too wide, and an insider would spot that it's got the wrong walls and ceiling. And Tower Bridge was built in 1894, so some years after Holmes' fateful adventure with the chap with chalk on his lapel. But that's me desperately trying to find fault with the thing. Go see; it's really good.

Oh, and the church down the road is now extolling that Jedward is a lot like the story of Jesus:

Saturday, November 21, 2009

Victorian rhapsody

There seemed to be too audiences for the event – the goths affecting the age with barely corsetted flesh and those wanting to perambulate round the Points of View exhibition (free until 7 March 2010), which tells the history of photography through some rare and extraordinary images.

We ably straddled both factions. The exhibition is glorious – and free. There's film explaining the difference between the Daguerre and Fox Talbot methods, and a wealth of nineteenth century capturings from all round the world.

The Dr was thrilled by the archaeological specimens – including that famous shot by Corporal J McCartney of Charles Newton and the ropes round the lion of Cnidus, on which she wrote a book. I loved Philip Henry Delamotte's images from the construction of the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, including my beloved monsters.

There was also the splendid Victorian hippopotamus and an astonishing nineteenth century photographic atlas of the moon, and photography changing our understanding of family, history, science and our own time. The explanatory panels delved into the politics of photographing empire and criminals, and the assumptions made by the “reality” of the image. There were gems embedded all through the thing, and I will have to go again.

It perhaps dwelt too much on the process and practice of photography, with less on the way the ordinary punter might collect, display and use the images. And, of course, the shop was shut by the time we came out, so there was no chance of checking which images exist as postcards.

Friday, November 13, 2009

Then welcome

It's a fun film, in which Annette Badland and Patricia Hodge are competing to make the best jam, as judged by Frank Skinner. The cast includes Linda Bellingham, Paul Daniels and Debbie McGee, Stephen Fry, Gary Rhodes and Philip Schofield. And also, on the left-hand back row, two other chums of mine.

Having dabbled a bit in short films myself this year (I was a runner on "Origin", a crucial-to-the-plot copper in "Girl Number 9" and am trying to set up my own effort at the moment), was really impressed by the look of the thing, the money on screen, the comic timing and just what can be achieved for next-to no money. Damn them.

On the strength of this short, I'm keen to see what they can do with Clovis Dardentor, the feature film they're trying to set up, based on a little-known Jules Verne novel from 1896 and also adapted by Lizzie. You can help by buying a credit.

The event at BAFTA was packed with frighteningly young and pretty people. I hunched in a corner with a couple of folk I already knew, feeling old and ugly. But there was a free beer, and mostly I was just consumed with envy.

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

Three items with increasingly tenuous links to Victorians

Secondly, you’ve five days left to hear the Radio 3’s Sunday night feature, “Vril”. Says the BBC's own website:

“Matthew Sweet finds out about Vril, the infinitely powerful energy source of the species of superhumans which featured in Victorian author and politician Edward Bulwer Lytton's pioneering science fiction novel The Coming Race (1871). Although it was completely fictional, many people were desperate to believe it really existed and had the power to transform their lives. With a visit to Knebworth House, Lytton's vast, grandiloquent Gothic mansion, where Matthew meets Lytton's great-great-great-grandson, and hears how his book was meant to be a warning about technology, soulless materialism and utopian dreams. At London's Royal Albert Hall, he discovers how a doctor, Herbert Tibbits, along with a handful of aristocrats, tried to promote the notion of electrical cures and the possibility of a 'coming race'. Along the way, Matthew and his contributors consider why so many English people have been so desperate to see the fantasy of regeneration transformed into fact.”Thirdly, last night the Dr and I attended a special screening of Slumdog Millionaire, followed by a Q and A with director Danny Boyle.

A lowly “chai wallah” in Mumbai makes it to the last round of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? The police can’t believe he’s not cheating, so attach electrodes and smack him about. Slowly they unfold his story…

It’s a great, on-the-whole feel-good film, probably Boyle’s best since Trainspotting. In fact, it’s full of the same chases, frenetic editing, wild mix of comedy and horror, and even a bit that’s quite like the “worst toilet in Scotland”. It’s fast and noisy and vivid, buzzing with wild, desperate life.

Jamal’s brother and the use of local talent (plus Dev Patel from Skins) reminded me of Children of God, but screenwriter Simon Beaufoy says its “Dickensian”. I can kind of see that, with the comedy and tragedy as pressed together as the very rich and very poor. It made me think of Charles Booth’s 1891 poverty map of London – which I only saw last week. There are issues of urban development, social mobility and education that might spring from Victorian novels or pamphlets. Yet Dickens made much more memorable wrong ‘uns – there’s no Skimpole, Micawber or Dombey here, just a motley crew of hoods.

The questioners – uniquely, in my experience – didn’t ask for advice for budding film-makers but instead challenged Boyle on the morality, truth and disregard for the horizon in his films. Some who knew India expressed amazement at his getting past red tape and state interference (he said they allowed the film to show police torturing a suspect so long as it involved no one of higher rank than inspector).

He talked about the complex moral quagmire of casting people from the real slums: does he take them and their families to the Oscars? And he explained that, with Disney and Sony already producing their first films in Hindi, we’re going to see much more erosion of the line between Bolly- and Hollywood.

Afterwards, we went for a pizza and shared a bottle of wine and a Banoffi pie. The Banoffi pie was, of course, first invented by Nigel McKenzie for the Hungry Monk restaurant, Jevington, in 1972. No, I can’t think of a way to link this last bit to the Victorians.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Stamp duty

Royal Mail is fast running out of solid ground under it, like the polar bears. Branches of Post Office are closing up and down the country – which, one claimant argues, is a breach of human rights.

There was also a story a couple of weeks ago that, since 2006 and the end of Royal Mail’s 350-year monopoly on delivering post in this country, nobody’s actually come forward to try to compete.

It’s apparently just not worth their while; the volume of letters is declining at the same rate as the polar icecaps. And of course, the postal regulator thinks the solution to this is privatisation.

The mail system we understand today is a Victorian invention – Rowland Hill’s revolutionary “Post-office reform: its importance and practicability” was published in 1837, the year Victoria gave up being a princess.

Hill begins his argument for reducing the cost and complexity of the postal system with some numbers. Taxing postage is counter-productive, he says. The tax deters people from using the state-owned mail, and fewer people using the system means less revenue to the state overall – Hill himself quotes a loss of some half a million pounds for 1835 on page 2.

“The loss to the revenue is, however, far from being the most serious of the injuries inflicted on society by the high rates of postage. When it is considered how much the religious, moral, and intellectual progress of the people, would be accelerated by the unobstructed circulation of letters and of the many cheap and excellent non-political publications of the present day, the Post Office assumes the new and important character of a powerful engine of civilization; capable of performing a distinguished part in the great work of National education, but rendered feeble and inefficient by erroneous financial arrangements.”

Rowland Hill, “Post-office reform: its importance and practicability” (1937), p. 7.

Admittedly, Hill argued that the system would probably be better administered in private hands:“There cannot be a doubt that if the law did not interpose its prohibition, the transmission of letters would be gladly overtaken by capitalists, and conducted on the ordinary commercial principles, with all that economy, attention to the wants of their customers, and skilful adaptation of means to the desired end, which is usually practised by those whose interests are involved in their success.”

Ibid.

But, since there is a monopoly, he argued, the state had a duty to make the system work, to make it work well, and to maximise revenues. And, because it had a monopoly, the costs would be easily spread across the whole country. In fact, if you had a national network anyway, the difference in cost of sending a letter 100 miles rather than 10 was almost negligible; either way, it was still even less than a penny.So Hill rather brilliantly argued that you would raise revenues by at least quartering the price of postage (from the usual 4d) – and paying the fare in advance of posting, to avoid people cheating the system.

“I therefore propose –

That the charge for primary distribution, that is to say, the postage on all letters received in a post-town, and delivered in the same, or any other post-town in this British Isles, shall be at the uniform rate of one penny per ounce ; – all letters and other papers, whether single or multiple, forming one packet, and not weighing more than one ounce, being charged one penny ; and heavier packets, to any convenient limit (say one pound,) being charged an additional half penny for each additional half ounce.”

Ibid., pp. 33-34.

While Hill also called for a “great increase” in the number of receiving houses, he argued that a uniform rate of postage would make their job easier and more efficient: letters would either be paid for or not, so they’d just need distributing. It’s not dissimilar to recent discussions of micropayments: if there’s a system of handling them cheaply and efficiently, then there’ll be enough of them to make it pay.And Hill’s brilliant system worked.

“In 1839 on average each person in the UK received just 4 letters a year. That figure doubled in 1840 to 8; in 1871 it was 32; by 1900 it had almost doubled again to 60.”

Simon Eliot, “Aspects of the Victorian Book – The Economic and Social Background to Victorian Print Culture: postal system”.

(See the graph at the foot of the page for the extraordinary scale of that…)

The Penny Black, the world’s first postage stamp, was issued on 6 May 1840. Soon there were wildly exciting technological developments like envelopes and, in 1843, Hill’s mate (and something of a hero of mine) Henry Cole invented the Christmas card. Hill, still the radical pioneer, was suggesting outlandish things like people having letter shaped holes in their front doors to make delivering post that much easier.

“Reducing the cost of mail would be a boost to literacy and democratise the use of the post,” says the British Postal Museum and Archive – arguing that Hill’s changes to the system were a deliberate social reform. But cheaper postage (and speedier services when post got sent my rail and, in London, it’s own private underground train) benefited everyone: the workings of business, of Empire, of news and thought and science were all given a great push.

As a result, and with Hill’s reforms being quickly adopted abroad, the world became a smaller place; our conversations became more widespread, diverse and quicker.

It’s no wonder that many commentators feel Hill’s postal system has been undone by the Internet – which, since 1990, has had just as huge an impact on worldwide work and natter. But the Internet is not the guilty party; the killer has been choking Hill’s system since long before 1990. Hill argued that the system would work because Royal Mail had its monopoly, and it is whittling away that monopoly that is causing the harm.

Telegrams, phonecalls and later faxes and pagers all competed with old-fashioned post; the speed and convenience of modern technology making many kinds of letter redundant. No longer would a courting couple arrange their dates by post; instead they’d enrage their parents by spending all night saying nothing down the phone.

But until (relatively) recently these technologies were no threat to Hill’s system because they too were part of Royal Mail’s monopoly. With its Victorian communication network set up, Royal Mail was inevitably in the best place to nurture the nascent technologies of telegraph and phone. Telegrams were sent and received from the local Post Office, and via cables that swam from Porthcurno in Cornwall, they reached the whole of the world. Britain’s telephone network was run by the General Post Office until 1980 – when British Telecom was created.

Now I’m not arguing that the telephone lines be renationalised. (But I can see an argument for making letters and parcels part of BT’s licence, that they’re as much “telecommunications” as telephone lines and broadband.) I’m just making the point.

But where the Royal Mail really was screwed was by being split into three. They separated the businesses of delivering letters, delivering parcels and operating post offices in 1986.

Oddly, Rowland Hill might have approved of this split. Having outlined his proposals for the fee of “an additional half penny for each additional half ounce” on parcels, he conceded his own doubts:

“The charge for weights exceeding one ounce should not, perhaps, in strict fairness, increase at so great a rate ; but strict fairness may be advantageously sacrificed to simplicity ; and it is perhaps not desirable that the Post Office should be encumbered with parcels.”

Hill, p. 34.

And yet, I’d argue that the parcels – and post that needs signing for – is the profitable bit. It’s the service you pay a premium on, and it’s the bit phone, fax and email can’t do. Tellingly, Parcelforce doesn’t have a monopoly on this stuff and – as Hill did sort of predicted (see above) – capitalists have skilfully, economically made parcels big business. There are expensive, elaborate advertisements for why one courier’s that millisecond quicker or how you can follow the progression of what you’ve sent to the square quantum particle.And it’s simple to see why: the transmission of abstract ideas can be done in the electronic ether, as fast and free as available technology; but you’re always going to need someone to shift physical stuff.

And the Internet, I’d argue, has increased the postage of physical stuff. People shop online and then have their wares sent to them from all over the country and even from abroad. They swap stuff, they auction stuff, they send gifts to the people and communities they met online. All the stuff you can’t just do by talking, that needs someone getting off their arse.

It’s difficult to quote any numbers when the infrastructure is in bits, but without competing couriers paying for lavish advertisements, or even paying separately and on top of each other for their networks to have the same reach, surely it’d be cheaper for all of us to send stuff. And, on Hill’s model, that means we’d do it more.

Dividing the postal system up ever further is just slash and burn economics; you strip out the bits of an ecosystem that will yield short term returns, but you do so at the expense of that system having a future.