"a deep dive into the life and career of story editor David Whitaker in LOOKING FOR DAVID."

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

Doctor Who: Season 2 Blu-ray

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Head of Drama, by Sydney Newman (with Graeme Burk)

Burk had access to the Newman archive, and I'm beside myself with envy at some of the material he's had at his fingertips. The Ur-text of all Doctor Who archaeology is the 1972 book The Making of Doctor Who by Malcolm Hulke and Terrance Dicks. According to Burk, Hulke wrote to Newman on 6 August 1971 asking him for memories of how the programme came about. On 28 September, Newman replied:

“I don't think I'm immodest in saying that it was entirely my concept, although inevitably many changes were brought about by Verity Lambert, who was its first producer. She would be the very best source of information, better than say, David Whitaker or even Donald Wilson.” (pp. 448-449)

However, by the time Newman sent this, Hulke had spoken to Donald Wilson (on 8 September) who told him what's generally considered the fact: that Doctor Who was created by Newman and Wilson.

“It was just Sydney and I together, chatting. At an early stage we discussed it with other people, but in fact the title, as I remember, I invented…” (p. 450)

Burk digs into this, citing some counterclaims, analysing the surviving paperwork from those early days and addressing the issue that some key papers appear to be missing from the archive. I've some more to add to this in my forthcoming book on story editor David Whitaker.

Anyway, Doctor Who is just one of the many, many shows Newman worked on. Head of Drama conveys the extraordinary range and impact of his work, from documentary films to opera and everything in between. There's what he learned from double-checking ticket sales in a cinema and watching the reactions of different audiences to the same film, and what working in newsreel and sport taught him about staging drama. He delights in telling us when he got something wrong - he was against employing chat-show host Ed Sullivan, tried to cancel the Daleks and resisted Donald Wilson in commissioning The Forsyte Saga.

But time and again, Newman's instincts for what would be popular and connect with a broad audience were dead right. Just one example of his many, many insights here:

“I laid down some simple notions [while at ABC]. Some people become physically ill when they see blood, and only a fool wants an audience to puke. Ergo, show blood with care. Some in the audience are daffy with hate, so don’t show them how to make a bomb. Viewers will identify with the innocent character, so being bound and helpless and tortured becomes powerfully disturbing, and that kind of reaction is a turn off. And finally, avoid common, easily available weapons such as a kitchen knife, so as not to provoke a viewer who may be feeling momentary murderous rage to act upon it in the moment.” (p. 304)

Newman gives full credit to the many writers and producers and talented people he worked with, but he's an amazing, funny and honest storyteller. There are some amazing stories here. Just before the Second World War, he was offered a job with Disney but had to head to back to Canada to sort out a visa. On the way, a fellow passenger seems to have reported him - as being an illegal immigrant from Mexico! The result was jail and some very hairy moments, but Newman tells it all with compassion and a wry smile, tying it all into a broader theme of having always been an outsider, an exile. And then he concludes that without this sorry business and the problems of a visa, had he been able to take that Disney job, he'd have ended up drafted into the US army and killed at Iwo Jima.

He shrugs that all off and is then onto the next drama.

Friday, June 24, 2022

On the Sixth Doctor Who

Foreword by Simon Guerrier

Thursday, 15 March 1984

My first thought is “good.” Janet Ellis on Blue Peter has just introduced Colin Baker as the new Doctor Who. My family don't buy newspapers and no one's said anything at school, so I'm pretty sure this is the first time I learn that Peter Davison is leaving. I've still not forgiven him for replacing Tom Baker.

Friday, 16 March 1984

The poisonous bat poo the Doctor touched three weeks ago finally kills him. My elder brother and sister join me and my younger brother to watch part four of The Caves of Androzani. I think it's the first time they – now serious, grown-up teenagers – have watched since The Five Doctors. They tell us, as always, that Doctor Who used to be much scarier than this sorry nonsense. I'm certain they're right and can't wait for this story to finish so we can get on to the new Doctor as he's sure to make everything better. I mean, a boy at school insists Colin is Tom Baker's brother.

Thursday. 22 March 1984

The Sixth Doctor era proper begins with part one of The Twin Dilemma. It's a very intelligent story – it must be, as I'm not always sure what's happening or what the Doctor is talking about. It's not exactly a scary story, but the Doctor attacking poor Peri and then later hiding behind her for safety means we're not sure what to make of him. “Look how clever they're being,” I'd tell my siblings if they asked my opinion. But they don't.

Saturday, 5 January 1985

A boring shopping trip to Southampton turns out to be a brilliant trick by my parents, and me and my younger brother are really off to see the stars of Doctor Who in the pantomime Cinderella. Colin Baker runs on to the stage pushing a shopping trolley with a Doctor Who number plate on it, to the most deafening cheer from the audience. People really love his Doctor! My parents' ingenious plan is to see the matinee performance so that we can be home in time for the first episode of the new series of Doctor Who on TV. But we get caught in traffic because of a football match, so I miss Part One of Attack of the Cybermen. There is much weeping.

Saturday, 12 January 1985

I sit entirely baffled by what's happening in Part Two of Attack of the Cybermen, certain it would all make sense if only I'd seen part one. (I don't get to see part one until 1993, and am still not entirely sure what's happening.)

Saturday, 26 January 1985

Part Two of Vengeance on Varos gives me nightmares. I'm really creeped out by the monstrous Sil and the story is full of horrid details, but what really gets me is when the Doctor rescues Peri from being turned into a bird. She looks human but the Doctor has to keep repeating her name to re-imprint her identity. The thought I can't shake is that she might be permanently changed, a monster on the inside...

ITV shows The A-Team at the same time as Doctor Who. After some discussion with my brother and a friend who doesn't have a telly so is often round to watch ours, we agree to video part one of The Two Doctors and watch The A-Team live. I distinctly remember the logic involved: Doctor Who is the one we'll want to watch more than once. It's not as slick, the fights aren't as good, and it's not so loved by our schoolmates but there's more to each episode. Good thinking, eight year-old me.

Saturday, 9 March 1985

I completely love Part One of Timelash. At school the next week, I insist to a friend that of course bumbling Herbert will be the new companion.

Saturday, 23 March 1985

The scariest moment ever seen in Doctor Who – at least, I think so now. Natasha finds her father, who's being turned into a Dalek and begs her to shoot him. The writing, performance, effects and music are all perfectly horrible. These days, I show a clip of this in talks I give on Doctor Who – just to see the audience squirm. After one talk, the parents of a keen young fan make a point of apologising to me for having told their daughter that Doctor Who wasn't very good in the 1980s.

Saturday, 30 March 1985

We're still watching The A-Team live and videoing Doctor Who, each week recording over the previous episode on the one tape we're allowed to use. Part Two of Revelation of the Daleks is the final episode of this year's series so doesn't get taped over the following week. My younger brother's interest in Doctor Who is waning but my three year-old brother Tom watches that tape again and again for weeks. A moment in that episode haunts me each time I see it, even now. As the Doctor runs down a corridor on his way to battle the Daleks, he thinks he hears Peri being exterminated. There's a moment of horror, of pain, on his face, and then he rallies himself and runs on. No words, just how Colin Baker plays it, so perfectly the Doctor.

Sometime in April 1985

It's all my pocket money, but I spend the vast sum of £1 on the 100th issue of The Doctor Who Magazine. It's a massive disappointment, lacking the weird wonder and excitement the TV series kindles in me. Instead, the magazine is full of lengthy, dense articles about the minutiae of the programme's past. I cannot fathom why anyone would find this of interest. I don't buy DWM again for five years.

Summer 1985, Winter 1985, Spring 1986

Then there's a gap. It came as a complete surprise to me, many years later, to learn that Doctor Who had been on hiatus for 18 months, that there'd been criticism of the violence in the programme, that it was even discussed on the news. At the time, I don't spare the absence a thought – of course Doctor Who will be on again at some point. I don't know there's been a new Doctor Who story, Slipback, on the radio until its released on cassette years later. But I've begun producing my own Doctor Who stories in which my brothers are horribly killed by various monsters.

Tuesday, 24 June 1986

I'm pretty sure I get the novelisation of Timelash for my 10th birthday. The TV version is my favourite of the Sixth Doctor's stories to date, and I read the book over and over. One big appeal is the references to the Third Doctor who, thanks to the Target books I've been picking up second hand and from the library, is my all-time favourite Doctor. But the story also really grabs me, and I spend the summer leaping over the garden sprinkler to be banished back in time.

Saturday, 6 September 1986

Doctor Who returns in a story called The Trial of a Time Lord. I'm especially pleased because we had a school trip to the “ancient” farm at Butser Hill used as a location. But otherwise the first four episodes seem to leave little impression. My memories of the Doctor Who I watched in the 1980s are usually vivid, but when I watch Part One of Trial again on video years later, I'm amazed to discover I can't recall any of what happens next. Perhaps Doctor Who wasn't affecting me as deeply as it once did – no longer the terrifying experience I couldn't bear to miss. Or perhaps these first episodes of the story were completely blotted out of my memory by the ones that followed.

Saturday, 4 October 1986

I am properly terrified by the return of Sil from last year's Vengeance on Varos. This section of the Doctor's trial is the last time Doctor Who ever really scares me. Part of the reason I've stuck with the series all these years on is the morbid hope it will scare me like that again.

Saturday, 1 November 1986

Bonnie Langford makes her début as Mel. My wife says this is when she made the decision to stop watching Doctor Who, which means she still doesn't know the outcome of the Doctor's trial. (Don't tell her.)

Saturday, 6 December 1986

The final episode of The Trial of a Time Lord – and of the year's Doctor Who.

Saturday, 13 December 1986

I sit through hours of programmes on BBC One before the dismal truth sets in that one 14-episode story is all we're getting.

Thursday, 18 December 1986

Colin Baker, in his Doctor Who costume but not quite in character, appears as a team captain on the Tomorrow's World Christmas special. I take this as irrefutable evidence that he's busy filming the new series which must surely start on TV early in the new year. I can't wait!

Monday, 2 March 1987

Janet Ellis on Blue Peter has news about the next series of Doctor Who – and chats to her mate Sylvester McCoy who is going to be the new Doctor. I am flabbergasted. Sylvester McCoy is from children's programmes!

Monday, 7 September 1987

The unceremonious end of the Sixth Doctor, who dies by falling over in the TARDIS before the opening titles of Time and the Rani Part One. I sharply recall my embarrassment at how silly the rest of the episode is, sure Doctor Who has lost its way. I've also just started secondary school, and realise that Doctor Who is no longer a programme to be fiercely discussed in the playground over the next week. I mention this to a friend who's gone to a different secondary school and he's astonished. “Are you still watching Doctor Who?”

But I am. It becomes a guilty pleasure. I know – because people keep telling me – that Doctor Who is not as good as it used to be. It was once something everybody watched but now I know hardly anyone who'll admit to having seen the latest episodes.

Today, I know there were problems behind the scenes of the programme: disagreements between those making it, a lack of interest high up at the BBC, a dozen other things. I avidly read – and contribute to – articles in DWM poring over exactly what was to blame. But I also know it was as much to do with the age me and my friends were at the time, and the other pressures and interests affecting us. They simply outgrew this children's programme while I couldn't let it go.

The upshot is that the Sixth Doctor's era marks a fundamental change in my relationship to Doctor Who. Whatever anyone else thinks of this period of the show – and Neil and Sue are about to share their own strong opinions on it – it holds a special place in my heart.

Because at the start of Colin Baker's time as the Doctor, the programme was something I shared with pretty much everyone I knew. By the end, it was mine.

Simon Guerrier

24 April 2017

Thursday, June 23, 2022

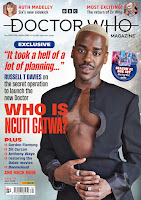

Doctor Who Magazine #579

As well as all this, there's a new "Sufficient Data" infographic from me and Ben Morris, this time on the ages and ages of the actors playing Doctor Who.

Wednesday, June 08, 2022

Competition, by Asa Briggs

Very quickly after launching in September 1955, ITV offered more hours of entertainment than the BBC. Advertising revenue also quickly made ITV very profitable - a one-shilling share in 1955 was worth £11 by 1958 (p. 11). With more money on offer, there was a huge flow of talent from the BBC; 500 out of 200 staff members moved to ITV in the first six months of 1956. The result was a desperate need for new people and a sharp rise in fees, doubling the cost of making an hour’s television (p. 18). Audiences responded to the fun, less formal ITV. The low point for the BBC came in the last quarter of 1957,

“when ITV, on the BBC’s own calculations, achieved a 72 per cent share of the viewing public wherever there was a choice.” (p. 20)

A lot of what follows is about the BBC’s concerted efforts to claw back that audience. But the book is as much about rivalry inside the BBC - the infighting of different departments, the effort to make the new BBC-2 different from and yet complementary to BBC-1, and the ascendance of TV over radio.

The latter happens gradually but with telling shifts. Since 1932, the monarch had addressed the nation each Christmas by radio; in 1957, Queen Elizabeth made the first such broadcast on TV (p. 144). That seems exactly on the cusp of the audience making the switch: in 1957 more radio-only licences were issued than radio-and-TV licences (7,558,843 to 6,966,256); in 1958 there were more TV-and-radio than radio-only licenses (8,090,003 to 6,556,347) (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). There’s a corresponding flip in the money spent on the two media: in 1957-8, expenditure on radio was more than on TV (£11,856,120 to £11,149,207); in 1958-9, more was spent on TV than radio (£13,988,812 to £11,441,818), and that gap only continued to widen (source: Appendix C, p. 1007). Yet aspects of BBC culture were slower to shift: Briggs notes that “The Governors … held most of their fortnightly meetings at Broadcasting House [home of radio] even after Television Centre was opened [in the summer of 1960]” (p. 32).

Television was expensive to buy into: the “cheapest Ferguson 17” television receiver” in an advertisement from 1957 “cost £72.9s, including purchase tax” (p. 5). Briggs compares the increased uptake of TV to the ownership of refrigerators and washing machines - 25% of households in 1955, 44% in 1960 - as well as cars (p. 6). So there was more going on that what’s often given as the reason TV caught on - ie the chance to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953. The sense is of new prosperity, or at least an end to post-war austerity. Television was part of a wider cultural movement. The total number of licences issued (radio and TV) rose steadily through the period covered, from 13.98 million in 1956 to 17.32 million in 1974 (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). By 1974, the Report of the Committee on Broadcasting Coverage chaired by Sir Stewart Crawford felt, according to Briggs, that,

“People now expected television services to be provided like electricity and water; they were ‘a condition of normal life’.” (p. 998)

This increase in viewers and therefore in licence fee revenue, plus the competition from ITV, led to a change in attitude at the BBC about the sort of thing they were doing. Briggs notes that the experimentalism of the early TV service gave way to more and more people speaking of “professionalism” - skill, experience and pride in the work being done (p. 24). I’m struck by how those skills was shared and developed:

“The Home Services, sound and television, gain … from the fact that they are part of an organisation of worldwide scope [with staff] freely transferred … from any one part of the corporation to another [meaning that Radio and TV had] a wide field of talent and experience to draw upon in filling their key positions”. (pp. 314-15)

There are numerous examples of this kind of cross-pollination. Police drama Dixon of Dock Green was produced by the Light Entertainment department. Innes Lloyd became producer of Doctor Who at the end of 1965 after years in Outside Broadcasts, which I think fed in to the contemporary feel he brought to the series, full of stylish location filming. Crews would work on drama, then the news, then Sportsview, flitting between genre and form. Briggs cites a particular example of this in two programmes initiated in 1957 following the end of the “toddlers’ truce”.

For years, television was required to stop broadcasting between 6 and 7 pm so that young children could be put to bed and older children could do their homework. But that meant a loss in advertising revenue at prime time, so the ITV companies appealed to Postmaster General Charles Hill, who was eventually persuaded to abolish the truce from February 1957. But what to put into that new slot?

“Both sides [ie BBC and ITV] recognised clearly that if viewers tuned into one particular channel in the early evening, there was considerable likelihood that they would stay with it for a large part of the evening that follows.” (Briggs, p. 160)

The BBC filled the new gap with two innovative programmes aimed at grabbing (and therefore holding) a very broad audience. From Monday to Friday, the slot was filled by Tonight, a current affairs programme that basically still survives today as The One Show. The fact that it remains such a staple of the TV landscape can hide how revolutionary it was:

“Through its magazine mix, which included music, Tonight deliberately blurred traditional distinctions between entertainment, information, and even education; while through its informal styles of presentation, it broke sharply with old BBC traditions of ‘correctness’ and ‘dignity’. It also showed the viewing public that the BBC could be just as sprightly and irreverent as ITV. Not surprisingly, therefore, the programme influenced many other programmes, including party political broadcasts.” (p. 162)

Briggs argues that part of the creative freedom came because Tonight was initially made outside the usual BBC studios and system, as space had been fully allocated while the truce was still in place. The programme was made in what became known as “Studio M”, in St Mary Abbots Place, Kensington. But the key thing is that this informality, the blurring of genre, spread.

“This [1960] was a time when old distinctions between drama and entertainment were themselves becoming at least as blurred as old distinctions between news and current affairs and entertainment.” (p. 195)

|

| Jon Pertwee, Adam Faith Six-Five Special (1958) |

“along with a number of other Saturday programmes, it [Six-Five Special] helped to reconstruct the British Saturday, which had, of course, begun to change in character long before the advent of competitive television [and was, with Grandstand, part of] a new leisure weekend.” (p. 199)

Elsewhere, Briggs notes the impact of TV - especially of ITV - on other forms of entertainment: attendance at football matches and cinemas dropped, with many cinemas closing (p. 185). Large audiences of varied ages were becoming glued to the box. I’d dare to suggest that this was not a “reconstruction” but the invention of Saturday, the later development of Juke Box Jury, Doctor Who, The Generation Game etc all part of a determined, conscious effort to compete with ITV with varied, engaging, good shows.

(On Sundays, the BBC continued to honour the truce, with no programming in the 6-7 slot that might compete with evening church services. From October 1961, the slot was taken by Songs of Praise.)

One key way of making good television was to write especially for the small screen. Briggs, of course, cites Nigel Kneale in this regard - though his The Quatermass Experiment and Nineteen Eight-Four are covered in Briggs’ previous volume. But Stuart Hood in A Survey of Television (1967) notes how sitcom grew out of the demands that TV placed on comedians:

"the medium is a voracious consumer of talent and turns. A comic who might in the [music or variety] halls hope to maintain himself with a polished routine changing little over the years, embellished a little, spiced with topicality, finds that his material is used up in the course of a couple of television appearances. The comic requires a team of writers to supply him with gags, and invention" (Hood, p. 152)

Briggs has more on this. For example, Eric Maschwitz, head of Light Entertainment at the BBC, remarked in 1960 that,

“We believe in comedy specially written for the television medium [and recognise] the great and essential value of writers, [employing] the best comedy writing teams [and] paying them, if necessary, as much as we pay the Stars they write for” (Briggs, p. 196-97)

Briggs makes the point on p. 210 that, “The fact that the scripts were written by named writers - and not by [anonymous] teams - distinguished British sitcom from that of the United States.” Some of these writers, such as Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, became household names. Frank Muir and Denis Norden appear, busy over scripts, in Richard Cawston’s documentary This is the BBC (1959, broadcast on TV in 1960): these are writers as film stars.

Hancock’s Half Hour (written by Galton and Simpson) and Whack-o (written by Muir and Norden) were, Briggs says, among the most popular TV programmes of the period, but he also explains how a technological innovation gave Hancock lasting power.

In August 1958, the BBC bought its first Ampex videotape recording machine. At £100 per tape, and with cut (ie edited) tapes not being reusable, this was an expensive system and most British television continued to be broadcast live and not saved for posterity. (Briggs explains, p. 836n, that Ampex was of more practical benefit in the US, where different time zones between the west and east coasts presented challenges for broadcast.)

From July 1959, Ampex was used to prerecord Hancock’s Half Hour, taking some of the pressure of live performance off its anxious star (p. 212). Producer Duncan Wood, who’d also overseen Six-Five Special, then made full use of Ampex to record Hancock’s Half-Hour out of chronological order,

“allowing for changes of scene and costume … Wood used great skill also in employing the camera in close-ups to register (and cut off at the right point) Hancock’s remarkable range of fascinating facial expressions … Galton and Simpson regarded the close-up as the ‘basis of television.’” (p. 213)

Prerecording allowed editing, which allowed better, more polished programmes. What’s more, prerecording meant Hancock’s Half-Hour could be - and was often - repeated, even after his death. The result was to score particular episodes and jokes - “That’s very nearly an armful” in The Blood Donor - into the cultural consciousness. Another, later comedy series, Dad’s Army, got higher viewing figures when it was repeated (p. 954).

|

| Clive Dunn, Michael Bentine It's a Square World (1963) |

Briggs says of the appeal of the later Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which he insists on referring to as “the Circus” rather than the more common “Python”) that,

“It took basic premises and reversed them. It’s humour, which was visual as much as verbal, again often succeeded in fusing both.” (p. 950)

More than that, it was comedy that spoofed and subverted the structures and furniture of television itself. In this, it surely owed a big debt to Bentine.

He’s not the only one to have been rather overlooked in histories of broadcasting. I’ve seen it said in many different places that Verity Lambert, first producer of Doctor Who, was also at the time,

“the BBC’s youngest, and only female, drama producer” (Archives Hub listing for the Verity Lambert papers)

Yet Briggs cites Dorothea Brooking and Joy Harington as producers of “memorable programmes” for the children’s department, referring to several dramas adapted from books. Harington had also produced adult drama - for example, she oversaw A Choice of Partners in June 1957, the first TV work by David Whitaker (whose career I am researching). In early 1963, “drama and light entertainment productions for children were removed from the Children’s Department,” says Briggs on page 179, with this responsibility going to the newly reorganised Drama and Light Entertainment departments respectively. Lambert may have been the only female producer in the Drama Department at the time she joined the BBC in June 1963. Except that Brooking produced an adaptation of Julius Caesar broadcast in November 1963, and Harington was still around; she produced drama-documentary Fothergale Co. Ltd, which began broadcast on 5 January 1965.

(Paddy Russell’s first credit as a producer was on The Massingham Affair, which began broadcast on 12 September 1964. Speaking of female producers, Briggs mentions Isa Benzie and Betty Rowley, the first two producers of the long-running Today programme on what’s now Radio 4 (p. 223). My sense is that there are many more women in key roles than this history implies.)

Stripped of responsibility for drama and light entertainment, the children’s department was incorporated into a new Family Programming group, headed by Doreen Stephens. According to Verity Lambert, this group was envious of Doctor Who - a programme they felt that they should be making. When, on 8 February 1964, an episode of Doctor Who showed teenage Susan Foreman attack a chair with some scissors, it was felt to break the BBC’s own code on acts of imitable violence. As Lambert told Doctor Who Magazine #235,

“The children’s department [ie Family Programming], who had been waiting patiently for something like this to happen, came down on us like a ton of bricks! We didn’t make the same mistake again.”

Lambert had to write Doreen Stephens an apology, so it’s interesting to read in Briggs that Stephens didn’t think violence on screen was necessarily bad. In a lecture of 19 October 1966, she spoke of “overcoming timidity” in making programmes, and believed that,

“violence and tension [don’t] necessarily harm a child in normal circumstances [while] in middle-class homes of the twenties and thirties, too many children were brought up in cushioned innocence … protected as much as possible from all harsh realities.” (Briggs, p. 347).

|

| "Compulsive nonsense" Doctor Who (1965) |

“The university lecturer Edward Blishen called Doctor Who ‘compulsive nonsense’ [footnote: Daily Sketch, 3 July 1964, quoting a Report published by the Advisory Centre for Education], but there was often shrewd sense there as well. At its best it was capable of fascinating highly intelligent adults.” (p. 424)

Beyond the specific subsection, there are other insights into early Doctor Who, too. For example, Briggs tells us that,

“nearly 13 million BBC viewers had seen Colonel Glenn entering his capsule at Cape Canaveral before beginning his great orbital flight [as the first American in space, 20 February 1962]. An earlier report on the flight in Tonight had attracted the biggest audience hat the programme had ever achieved, nearly a third higher than the usual Thursday figure [footnote: BBC Record, 7 (March 1962): ‘Watching the Space Flight’’]” (p. 844)

Could this have inspired head of light entertainment (note - not drama) Eric Maschwitz to commission - via Donald Wilson of the Script Department - Alice Frick and Donald Bull to look into the potential for science-fiction on TV. Their report, delivered on 25 April that year, is the first document in the paper trail that leads to Doctor Who.

Then there is the impact of the programme once it was on air. On 16 September 1965, Prime Minister Harold Wilson addressed a dinner held at London’s Guildhall to mark ten years of the ITA - and of independent television. Part of Wilson’s speech mentioned programmes that he felt had made their mark. As well as Maigret, starring Wilson’s “old friend Rupert Davies”,

“It is a fact that Ena Sharples or Dr Finlay, Steptoe or Dr Who … have been seen by far more people than all the theatre audiences who ever saw all the actors that strode the stage in all the centuries between the first and second Elizabethan age.” (Copy of speech in R31/101/6, cited in Briggs, p. 497).

Two things about this seem extraordinary. One, Wilson - who was no fan of the BBC, as Briggs details at some length - quotes four BBC shows to one by ITV. And at the time, Doctor Who was not the institution it is now, a “heritage brand” of such recognised value that its next episode will be a major feature in the BBC's centenary celebrations this October. When Wilson spoke, this compulsive nonsense of a series was not quite two years-old.

But such is the power of television...

More by me on old telly:

- Nigel Kneale: a centenary celebration

- The influence of The Inheritors by William Golding on the first Doctor Who story

- A Survey of Television by Stuart Hood

- Mary Whitehouse vs Doctor Who

- Starlight Days, by Cecil Madden

- Writing for Television, by Sir Basil Bartlett

- The Intimate Screen, by Jason Jacobs

- I’m Just the Guy Who Says Action, by Alvin Rakoff

Friday, May 27, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #578

Had it not been for this exciting announcement, the cover would probably have gone to Peter Cushing, star of the 1960s Dalek movies that are being re-released this summer. There is lots about the films this issue, including two things by me.

In "Sets and the City", Rhys Williams and Gav Rymill recreate the sets from the 1965 film Dr Who and the Daleks, with commentary by me and Rhys. This month's "Sufficient Data" infographic by me and Ben Morris charts actors from the first Dalek movie who were also in TV Doctor Who.

(By nice coincidence, almost exactly 20 years ago, my first ever work for DWM was a feature on that first Dalek movie and big-screen Doctor Who generally. That was a cover feature, too.)Plus, in "Hebe Monsters", I speak to Ruth Madeley about playing Hebe Harrison, new companion to the Sixth Doctor in his latest audio adventures.

Given all this, they've also put a photo of niceish me on page 3, taken by the Dr.

Thursday, April 28, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #577

A lot of attention has been given to Doctor Who Christmas specials, but to date 14 episodes have first been broadcast on Christmas Day, while 20 have premiered on Holy Saturday (the day between Good Friday and Easter Sunday):

- 28 March 1964 - Mighty Kublai Khan

- 17 April 1965 - The Warlords

- 9 April 1966 - The Hall of Dolls

- 25 March 1967 - The Macra Terror Episode 3

- 13 April 1968 - Fury from the Deep Episode 5

- 5 April 1969 - "The Space Pirates" Episode 5

- 28 March 1970 - Doctor Who and the Silurians Episode 2

- 10 April 1971 - Colony in Space Episode One

- 1 April 1972 - The Sea Devils Episode Six

- 21 April 1973 - Planet of the Daleks Episode Three

- 13 April 1974 - The Monster of Peladon Part Four

- 29 March 1975 - Genesis of the Daleks Part Four

- 26 March 2005 - Rose*

- 15 April 2006 - New Earth*

- 7 April 2007 - The Shakespeare Code

- 11 April 2009 - Planet of the Dead

- 3 April 2010 - The Eleventh Hour*

- 23 April 2011 - The Impossible Astronaut*

- 30 March 2013 - The Bells of Saint John*

- 15 April 2017 - The Pilot*

Six of those (marked with an asterisk) were the first of a new series, using Easter as part of the launch. Planet of the Dead (2009) and this year's Legend of the Sea Devils were special, one-off episodes for the Easter weekend.

Legend of the Sea Devils is the first episode of Doctor Who to debut on Easter Sunday itself. And the 1993 repeat on BBC Two of Revelation of the Daleks Part Four is the only episode of Doctor Who broadcast on terrestrial TV on Good Friday.

Friday, April 01, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #576

First, there's a tribute to the actor Henry Soskin who, as Henry Lincoln, co-wrote The Abominable Snowman and The Web of Fear, and - under another pseudonym - The Dominators. Lincoln then want on to investigate the Knights Templar, and co-wrote the best-selling The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. It was a fun challenge to dig through the various things said about - and by - him to piece together the true story was; how very fitting for him, I thought.

Then the latest instalment of Sufficient Data is on the different cat badges worn by the Sixth Doctor, as always illustrated by the amazing Ben Morris.

Saturday, March 26, 2022

17 years of new Doctor Who

But I wonder how Rose would look to someone coming to it only familiar with Doctor Who from Jodie Whittaker's Doctor. Would it seem so very different? In the intervening years, there have been new lead actors, the move to high definition TV, and there's a lot more CGI - but in its pace and feel and imagination, and in the character and motivations of the Doctor, it's still recognisably the same programme.

How that contrasts with the first time Doctor Who turned 17, on 23 November 1980. The night before that birthday, State of Decay Part One saw the Fourth Doctor and his companions - two aliens and a robot - meeting vampires in a bubble universe, in a clash of old mythology and cutting edge physics. A few weeks before, on 4 November, is was announced that Peter Davison would be taking over the title role in the series, a markedly younger actor than the previous incumbents, promising new life for the then-venerable series. And a little before that, on 25 October, the first episode of Full Circle made a big impression on me; it's the earliest thing I remember.

For a long time, to me Doctor Who before then was essentially myth. My elder siblings shared tantalising memories of Doctor Who stories from just a few years before that I thought I'd never see. Old Doctor Who had been better, scarier, stranger - and theirs. Then came fleeting glimpses of what had been. At the end of 1981, BBC Two repeated some old stories, including ones older than my siblings. I vividly remember the awe with which we met Doctor Who's very first four episodes, relics of another age.

For one thing, they were so strikingly different from the Doctor Who of 17 or 18 years later. They were black and white, but also dark and spooky and shot in a completely different way: long scenes with lots of close-ups, and little in the way of effects. There was also the character of the Doctor, this grumpy, cowardly, selfish figure - literally a different person, not just played by a different actor.

This extraordinary difference was evident to the people who worked on the programme. Jacqueline Hill, who played Barbara Wright in the first 18 months of Doctor Who, returned to the series in 1980 to play Lexa, an alien priestess. If Billie Piper, who played Rose, were to return to Doctor Who now, I wonder how much she'd share these sentiments:

"We did Meglos in different studios, and of course television had moved on in leaps and bounds so that the technique was completely different. The special effects were a lot more dominant. It was recorded entirely out of order and there was nobody working on the story who could remember as far back as me – which was something of a humbling experience. I did enjoy it very much, though, mainly because the part I played was so very different to the calm and unflappable Barbara. It was a happy reunion with a show that was really only the same show by name alone." (Jaqueline Hill in Doctor Who Magazine #105 (1985)

As it happens, this week I was in London to research more about the early days of Doctor Who and the people who made it - stuff now on the cusp of living memory. Since I was passing that way, I called in at a particular tree.

Wednesday, March 23, 2022

The Inheritors, by William Golding

"A man for pictures [ie thinking]. A woman for Oa [ie having children.] (p. 117)

"Clearly, the secret of fire-making has been lost, and so the fire must be transported as a constant. Likewise, in The Cave of Skulls, Hur tips ash ("the dead fire") over Za's kindling. Both Golding's and Coburn's Neanderthals have something like a religion - the first devoted to "Oa", a kind of "Earth-Mother", the other to "Orb", a sun-god. But perhaps the best reason for believing that Coburn was acquainted with The Inheritors lies in the similarities between Golding's Neanderthal names and Coburn's: the names of 'Ha', the leader, and the woman 'Fa', are echoed by Coburn's 'Za', for instance, with the male names 'Lok' and 'Mal' resembling ancestors of 'Kal'."(Alan Barnes, "Fact of Fiction: 100,000 BC", DWM #337 (2003))

"'Mal! Mal! We have meat!'

Mal opened his eyes and got himself on one elbow. He looked across the fire at the swinging stomach [of a doe they had scavenged] and panted a grin at Lok. Then he turned to the old woman. She smiled at him and began to beat the free hand on her thigh.

'That is good, Mal. That is strength.'" (p. 58)

KAL: My eyes tell me what has happened... as they do when I sleep and I see things. Za and Hur came here to free them, and find out the a way to make fire. The old woman saw them and Za killed old woman. Za has gone with them... taking them to their tree [ie the TARDIS]. Za is taking away fire.HORG: The old woman is dead. It must have been as your eyes said it was. (Doctor Who episode 3: The Forest of Fear]

"An earthquake in the petrified forests of the English novel."

Wednesday, March 02, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #575

There's also another "Sufficient Data" by me and Ben Morris, this time on the subject of antimatter to mark 40 years since it killed poor Adric.

Sunday, February 27, 2022

Mary Whitehouse v Doctor Who

Disgusted, Mary Whitehouse will be broadcast on Radio 4 on Saturday 5 March. Produced by me and brother Thomas, it’s presented by Samira Ahmed who has spent months researching Whitehouse’s diaries, now in the collections of the Bodleian Library in Oxford; Samira has written a blog post about it all. For our programme, we spoke to Whitehouse’s granddaughter Fiona, to critics Michael Billington and Nicholas de Jongh, and to actor / director Samuel West. Oh, and Lisa Bowerman is amazing as Mary Whitehouse.

I’ve spent weeks going through the BBC archives for suitable clips to use. The earliest surviving example is from 5 May 1964, a news report about the Clean-Up TV event held at Birmingham Town Hall, where Whitehouse was one of the speakers. The clip of Whitehouse is brief but quite well known:

“Last Thursday evening we sat as a family and we saw a programme that started at six thirty-five and it was the dirtiest programme that I have seen for a very long time.”

The consensus seems to be that this dirty programme was a Scottish sketch show, Between the Lines, starring Tom Conti and Fulton Mackay. On the edition of 30 April, Conti met an attractive woman at a dance and we then heard his internal monologue. Sadly, the episode seems to be missing from the archive, so we can’t tell how “dirty” it was. We can’t judge the language used, the tone of it, the general effect.

Surely, one would think, a programme shown at 6.35 in the evening couldn’t be too rude. And yet there’s lots in old telly that was thought innocuous at the time but seems remarkable now. The Wheel of Fortune is an episode of Doctor Who written by David Whitaker and first broadcast at 5.40 pm on 10 April 1965. It includes a scene in which a man called Haroun helps companion Barbara Wright to hide from some soldiers. Haroun leaves Barbara with his young daughter, Safiya, while he goes to look for a safe route out of town. He gives Barbara his knife: if she thinks the soldiers will find them, she is to kill Safiya and then herself. Barbara protests, but Haroun persuades her:

You would not let them [the soldiers] take Safiya?

No, of course I wouldn’t!

Then I'll leave the knife.

It’s an extraordinary thing to include in a family drama aimed at kids aged 8 to 14, and just one of several examples from early Doctor Who where Barbara is under threat of sexual violence.

Right from the beginning of Doctor Who, there had been questions about how suitable it was for children. Opinion on this was “strongly divided” at the executive meeting of the BBC’s Television Programme Planning Committee on 4 December 1963 - after just two episodes of the series had been broadcast. The following week it looked like the programme might be moved to a later time in the schedule, though this was over-ruled by Head of Drama (and co-creator of Doctor Who) Sydney Newman.

Then, on 12 February 1964, at the same committee Donald Baverstock (Chief of Programmes, BBC-1, listed in minutes as “C.P.Tel”) thought one scene in The Edge of Destruction - in which the Doctor’s granddaughter Susan attacks a chair with a pair of scissors while in the grip of some kind of madness - might have breached the BBC’s own code on depictions of inimitable violence. Baverstock’s then boss, Stuart Hood, later wrote that the BBC’s code of practice on violence in television, drawn up in 1960, was.

“a remarkably sane and enlightened document, which acknowledged the fact, for instance, that subjects with unpleasant associations for adults will often be taken for granted by children and vice versa. ‘Guns … and fisticuffs may have sinister implications for adults; seldom for children. Family insecurity and marital infidelity may be commonplace to adults; to children they can be deeply disturbing.’” (Stuart Hood, A Survey of Television (1967), p. 90.)

That reference to guns is interesting in the light of Mary Whitehouse’s first-known objections to Doctor Who. Whitehouse believed that depictions of sex and violence on TV had a corrupting effect on the viewer, and led to an increase in sexual and violent crime more broadly. She gave some examples of this in an interview with the Daily Mirror on 29 November 1965:

“‘I know a 14-year-old girl who was so physically affected by a sexy play that she went out and offered herself to a 14-year-old boy. … And I know a boy who listened to a doctor expounding the virtues of of premarital sex and went out and got VD… I mean, where is it going to end? We've even got the Daleks in Dr. Who—a children's show, mind you—chanting 'Kill, kill, kill.' One day a youngster is going to go out and do just that…’ AT this point MRS. FOX said something that sounded like ‘twaddle.’”

That’s Avril Fox, “mother and Harlow councillor”, contesting Whitehouse’s claims. I found several examples of this in the archive, too: Whitehouse claiming to represent the views of ordinary people, and then ordinary people quickly saying she didn’t speak for them. (We use one example in our documentary, from an episode of Talkback on 7 November 1967 in which Whitehouse and other members of the public responded to Stuart Hood and the claims made in his book, not least that most people who write into TV companies are “cranks”.)

I also found several examples of Whitehouse conflating what are surely different issues, such as in this case undercutting her point about protecting children from sexualised content by equating it with the supposed effects of fantasy violence. Yes, children mimic Daleks - that’s part of the Daleks’ appeal - but they don’t then go on to kill people. Suggesting they do undercuts the whole argument; the serious point about sexualised content is also dismissed as twaddle.

There’s a third characteristic: that Whitehouse may have been complaining about something she’d not actually seen. The Daily Mirror interview was published two days after the broadcast of Devil’s Planet, an especially notable episode of Doctor Who in that it killed off a companion. But Katarina is not killed by Daleks; she is ejected from a spaceship airlock. The Daleks do appear, and execute a wicked alien called Zephon, but there is no chanting of “Kill”.

Famously, the Daleks don’t chant “Kill”, but prefer the term “Exterminate”. One Dalek does repeat, “Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill,” in the episode Flashpoint (broadcast 26 December 1964), so either Whitehouse was remembering that untypical sequence from a year before, or she invented the thing she criticised - perhaps repeating what other people said about the Daleks, rather than what she’d observed herself. (As we detail in our documentary, she consciously chose not to see The Romans in Britain at the National Theatre, but led a private prosecution against its director for a scene in it that she considered to be grossly indecent.)

In her later criticism of Doctor Who, Whitehouse was more specific - and effective. Since m’colleague Jonathan Morris wrote about this in more depth in his 2003 feature for Doctor Who Magazine, “Sex and Violence”, a wealth of press clippings have been posted on the Doctor Who Cuttings Archive relating to Mary Whitehouse. Planet of the Spiders (1974) had, she claimed, led to an “epidemic” of “spider phobia” in children. In Genesis of the Daleks (1975),

“Cruelty, corpses, poison gas, Nazi-type stormtroopers and revolting experiments in human genetics are served up as teatime brutality for the tots.” (The Mirror, 27 March 1975)

She was concerned about specific scenes in The Brain of Morbius and The Deadly Assassin (both 1976), and could vividly recall them almost 20 years later when interviewed, on 22 November 1993, for the documentary Thirty Years in the TARDIS. Director Kevin Davies kindly provided me with a longer version of that interview, though we couldn’t make it fit in our programme:

“Now, there’s one particular programme - and I can see it still in my mind’s eye - where Doctor Who, the final shot of the episode, was Doctor Who drowning. And these sort of images, the final shots of the programme, with the image that was left in the mind of the child for a whole week, not knowing whether his beloved Doctor Who or whatever would have drowned or not have drowned. And another programme finished with a girl who was with him, and she had a pincer put around her neck. And the holding of that pincer round her, again, was the last shot. And to me, I think it’s extraordinary that people with the brilliance, in many ways, in making a programme of that kind couldn’t have extended their awareness not only to their cameras or all the rest of it, but to the effect of what they were doing upon the children who were receiving it. That was almost as thought they were a bit dumb in that area.”

Back in 1976, and following her criticism, the last shot of the drowning scene was cut from the master tape of the episode by the programme’s then producer. On the 30 Years documentary, a subsequent producer says he secretly hoped Mary Whitehouse would complain about his Doctor Who because it was always good for viewing figures; yet her complaints about violence in the series in his time overseeing the series were used as justification when the programme was then taken off the air. Today, Doctor Who isn’t shown so early in the evening and - I’d argue - is marketed much less as a show for children. I find myself wondering how much that sort of thing is in the shadow of Mary Whitehouse.

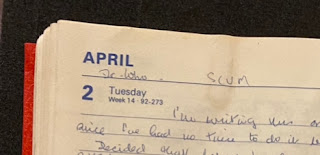

Going through her diaries, I found a number of other things. There’s the entry in the 1985 diary where she has two concerns about recent television: her discussions with Michael Grade, then Controller of BBC-1, about violence in the recent season of Doctor Who and the legal judgment on yet another private prosecution she’d brought, this time about the broadcast on Channel 4 of a controversial film set in a borstal. So the page is headed “Dr. Who - SCUM”

And another one I noted. On 18 March 1982, the legal case against The Romans in Britain was withdrawn. Mary Whitehouse was on that evening’s Newsnight to discuss the case, and spent most of her time correcting what she felt were errors in the reporting. Then, interview done, the cameras wheeled away to the other side of the studio for further discussion of the case, with Joan Bakewell speaking to Sir Peter Hall from the National Theatre and Sir Lois Blom-Cooper.

Again, Whitehouse thought what they said was wrong. In her diary, she says she asked the presenter who’d just interviewed her if she could intercede. The presenter checked with the producer who said no. So Mary Whitehouse heckled anyway.

“Whereupon the cameras came chasing across the studio, like a lot of Daleks, leaving Joan Bakewell and her guests in darkness! … I came fully onto the screen as I was saying my bit.” (Mary Whitehouse, diary entry for events of 18 March 1982, written on the page for 10 March 1982)

I was really struck by that moment - and that telling word. Alas, as the Daleks close in on Mary Whitehouse for this hero moment, she’s not clutching her lapels.

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

Doctor Who: Chronicles - 2007

For his article on the Doctor Who books published that year, Mark Wright spoke to me about writing The Pirate Loop, the one with the space-pirate badgers. The Dr still thinks that book is the best thing I've ever written, so it's been 15 years all downhill.

Wednesday, February 02, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #574

This one marks 50 years of Day of the Daleks and owes a little to the blog post I wrote a while ago on the economics of the Daleks.

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Few Eggs and No Oranges: The Diaries of Vere Hodgson 1940-45

They certainly do that. Hodgson wrote her diaries to share with family abroad, letting them know about life in London during the Blitz and the welfare of various relatives there and in Birmingham, too. We get to know these people - and feel the loss of those who die. Hodgson also updates us on various neighbours and friends, and keeps up with the latest news. She's got a keen eye for telling detail - about the war, about London, about extraordinary times.

Two things really help in her perspective. First, there's her job at the Sanctuary at 3 Lansdowne Road, run by the spiritualist Greater World Association Trust and doing a lot of good work during the war sorting out money, food and clothing for anyone in need. That gives Hodgson an insider's view of just how much damage was done by the bombing, the lives lived among burned-out buildings, the character of endurance. She skips days in her diary as she throws herself into the annual fund-raising fair, and despite the privations of war there's a sense of the community coming together and helping out. Every year through the war, there's more damage, more rationing, more difficulty - and yet they raise more money each time.

Secondly, Hodgson previously worked as a teacher in Italy - she once shook hands with Mussolini, she tells us, whose daughter was a pupil. As she follows news of allied troops ascending through Italy, she peppers her diary with first-hand knowledge: the landforms, tunnels, buildings and art being fought over, what it all actually signifies.

For my purposes, there's the sense of the nightly lottery as London is attacked. I spent a lot of time checking her reports of bomb damage against a street map, trying to judge - just as she does in her diary - how bad things really are, how close the bombs are to her home, how much danger she might be in. There's a good sense, too, of the over-fatigue that resulted from night after night of Blitz, as described as well by Judith Kerr in Out of the Hitler Time.

There's lots on what ordinary people did to prepare for the Blitz: on 1 July 1940, Hodgson had respirator drill at Kensington Town Hall; the next day she reported on shelters being built all over Kensington and the new orders that people were to continue in their work until they heard gunfire. On 11 July, she had a practice session in a chamber of tear gas and sat through lectures on gas. Four days later, there was a trip to the Gas Cleansing Station at Earls Court, then on the 18th she took a course on Fire-Fighting at the Convent of the Assumption on Kensington Square, in which she had to climb and drop from a 10-foot wall.

Then there's the things she finds surprising: on 14 August 1940, she was amused to hear people took shelter under dining tables in their homes (something she would herself do later). Or, after a night out to a play in Birmingham on 7 September 1941:

“In London theatre-going at night can be a nightmare in these difficult days." (p. 208)

That was not due to the bombs, but the lack of street lighting and buses to get safety home. A year later, on 13 September 1942, she was struck that,

“Nobody dresses in London these days, even at the smartest places.” (p. 315)

On 7 December 1944, she found it remarkable that,

“A [horse-drawn] Hansom cab is seen periodically doing duty round here. I gaze at it with great satisfaction. I never rode in one. They had just gone out when I had money to do such things. We also have to taxis..." (p. 544)

Yet working animals were a familiar sight to her. On 9 July 1944, she says - to show how life was going on as normal - that,

“Our milkman comes round as usual with his white pony.” (p. 494)

And I'm struck by her reference to Shepherds Bush, a shortish walk from where she lived, as,

“the next village to Notting Hill” (p. 565).

That sense is there in her local shops, all within walking distance: the Polish greengrocer who lets her have an extra orange, the cobbler, the cat-meat seller, the Mercury cafe where she sometimes has lunch alongside ballerinas from the Rambert school at the adjacent theatre.

As with Wartime Britain, several things here chime with the current pandemic. For example, on 5 July 1944, Hodgson is,

“Very sorry for children who have to take exams in Air Raid Shelters, not able to concentrate after a bad night.” (p. 491)

But I was looking specifically for anything that might echo in David Whitaker's later work on Doctor Who. A few things resonate. On 7 August 1940, Hodgson remarked on the great many refugees now in Kensington, because of "everybody leaving Gibraltar and Malta" (p. 28), and there are later references to refugees - these ones and more - grubbing along and needing support. That put me in mind of the Doctor and Susan as we first meet them, and also the Thals in the first Dalek story. Then, on 18 April 1943 Hodgson reported that the previous evening,

“Marie and I went to Petrified Forest. Setting in Arizona. All very exciting." (p. 379)

On 20 August 1944, she remarked of the new plague of V1 pilotless planes that,

“These Robots have changed everything. The Germans can, in the future, in complete secrecy underground, prepare in the years to come, more of such things and launch them on an unprepared world. … Men will perish under the machines that he has made.” (p. 517)

But when a few weeks later there was a lull in the bombing, it was more unnerving, as she reported on 3 September:

“Here we are at with the end in sight - and we are intact. The silence at the moment is / uncanny. After listening to sirens on and off all day and all night for ten weeks, it seems strange without them. Have we finished with them?” (pp. 526-527)

London is eerily silent at the beginning of The Dalek Invasion of Earth... Maybe Whitaker (and Terry Nation) didn't draw on this kind of stuff consciously - or at all - but it's made me think about the tone of the first two Dalek stories, and how much they're grounded in something that feels real, at least compared to third story The Chase, which Whitaker wasn't involved in. I need to think a bit more on this but that's where I am at the moment.

Oh, and then there's this from 30 November 1940 where, as Hodgson and her colleagues at the Sanctuary are busy with their charitable work, they compare notes on the previous night's Blitz:

“From Mrs Whittaker we heard that part of the roof of the Daily Telegraph had gone. Everything was so hot no one could go near.” (p. 100)

That might just be David's mother.

Wednesday, December 29, 2021

Journeys into Genealogy

Podcast website: https://journeysintogenealogy.co.uk

Also available on: