Arrived in Palma on Sunday evening, guests at the

Mallorca Marriott Son Antem Golf Resort and Spa. They rang up a few months ago on the basis of all the Marriott's I've stayed in over the years, offering a cheap break on condition me and the Dr sat through a pitch from them. We thought what the hell.

Surprised by how rude a lot of the passengers were on the Easyjet flight, barking and snapping at the staff as if they thought they were going first class. We taxied to the hotel to find it was packed out with golfing Germans. So the hotel offered us one of their three-bedroom villas with a bathroom each. Just the downstairs was bigger than our flat at home, with a jacuzzi bath and a telly in every cupboard.

Perhaps this was part of the pitch they were going to make us - it just seemed to good to be true. We unpacked, we bought some food and we sat outside and read

The Graveyard Book. When it got too cold to be outside, the Dr cooked and I discovered our tellies oddly got BBC One and Three. So we got to watch the finale of

Being Human.

Got up Monday and collected our welcome pack: a bottle of wine, a map of Palma and Mallorca, some coupons for the spa and other Marriott hotels, and a list of restaurants and beaches. The nice bloke reminded us of the pitch we'd have to attend the next day, and when I told him we'd not taken the hire car gave me advice on parking in Palma anyway.

After a healthy breakfast, we grabbed a taxi in town. The sun was out and we basked under it, in view of the striking cathedral,

La Seu.

It's an oddly blocky oblongs, tall flying buttresses kept in tight, so it feels more like a mad design from a fantasy movie rather than a real gothic building. The Dr was especially excited that

Antoni Gaudi had worked on tidying the place up at the turn of the twentieth century.

We made our way up the steps and made our way round to the left of the cathedral, in between it and the Almudaina Palace. The front of the cathedral could almost be brand new: immaculate pale stone framing the darker, more weathered medieval original. I struggled to get the grand majesty of the front into the frame of my mobile.

It was just €2.50 each to get in and we shuffled into the darkness. Yet the strangest thing about La Seu is that its so beautifully light.

Gaudi, we learned from the book we bought afterwards, unbricked the windows and brought in electric candles, part of a general movement in the church in the time to build up the response of the congregation, a movement which led to Vatican 2 in the sixties.

Of course my phone doesn't pick up on half the subtleties of the light.

Here's the other side of the main window which I'd snapped from outside. The colours are bright and cheery, not like other so many churches in Spain which I felt seek to cower and terrify.

I realise I've not written up my notes on Seville and Cordoba from last

September, but how different this simple grandeur is to the oppressive Catholicism of the

Mesquita. The extraordinary thing there is the beauty of the original mosque, and the heavy-handed vulgarity of the Christian imposition.

A lot of Spanish churches proclaim the patronage of the conquistadors and the awful power of the priests. In the Mesquita, that's like vandalism written in stone. And when you take pictures the architectural prowess of the Moors is even more self-evident. The Moorish bits shine in the natural, subtle light; the Catholic bits are dumped in their darkness.

But La Seu is nothing like that. Yes, there's the grotesque, bloody statues of martyrs and sinners alike. But the efforts in the early twentieth century, such as Gaudi moving the choir stalls to nearer the altar, created a whole new sense of space.

They're still working on the place; Gaudi's gold leaves around the altar shrouded by high scaffolding, reaching up into the heavens. Oddly, the workers up there had a radio on, and - muted yet still distinct - Robbie Williams' "Angels" curled round the cathedral.

But there was something about the modern pop music that worked. It seemed to fit La Seu's historic embrace with modern art and design, to engage with the people who come through its doors and the everyday detail of their lives.

To the right of the main altar is a chapel recently done up in style. The windows are shaded in grey, the gothic brickwork hidden behind cracked plaster that suggests the seabed. I assume its acknowledging the debt that Palma - and the island - owes the sea, and the price its people have paid in those who've not come back from the water.

There's the suggestion of skulls under the altar itself, and amorphous creatures float round the walls, which might be angels or jellyfish. It's a haunting and strange place, and a bold commission for such a church. But I found myself lingering there, drawn by its strangeness, trying to puzzle it out.

I then noticed the organ, set up high above the way we'd come in. Again it's oddly incongruous with the rest of the cathedral. My almost-black picture doesn't quite show how the pipes are arranged. There's a cluster of vertical tubes like most organs, then a line of horizontal ones striking out like a line of muskets or blunderbusses.

I've no idea if that's the intention, but the same thought struck the Dr independently. Perhaps she got better pictures...

There was a fun Victorian monument as we made our way out. I ignored the poor dead bloke on the slab and the respectable chap mourning behind him. To the right was this lady who seemed rather bored by the whole thing. And at her feet nestled a lion with the most marvellous boggling expression:

And lastly, there was a series of portraits telling the life stories of important saints. These can often be excitingly grisly, and sure enough the nearest panel shows a lady looking quite smug about having her head chopped off. Look at the smile on those innocent features. Behold her spurting neck.

I'm never sure in these kind of narratives what the call to action is meant to be. Are you meant to look on this work and feel consumed by outrage that a saint's been killed? Or when you see the horrid things done to them because they did right by God are you meant to think, "That could be me!"? Wouldn't that rather put you off coming back to church?

The sun awaited us outside. We emerged into cloisters with a good view back up at the buttresses, like seeing the tricks done backstage.

We filed out into the medieval streets and wandered a bit, looking in on a nice ornate garden, its pond stocked with bright, happy goldfish. We were making it up as we went along, no idea where we were going.

Then we made out way up the high street in the direction of the train station. It's funny seeing the familiar brand names and shops mixed up with things unique to a city. And I boggled at an advert in a shoe shop, not quite sure what it was trying to sell:

We arrived at the main train station and the Dr remembered something about an old-fashioned train journey that would take us up into the mountains. Had to leave the modern station and cross a road to find what we were after.

The train to Soller first opened in 1912, and still uses authentic wooden trains from before the invention of leg room. We gleefully piled aboard, and spent the hour journey reading and staring out the window at the orange trees and scenery. Once you're out of the industrial bits of Palma its really very beautiful. A young couple a few rows ahead of us snogged every time we went into a tunnel, but the Dr and I are too long married and jaded for anything like that.

The weather was turning when we reached Soller, and we nosed round two small, free galleries showing original works by Miro and Picasso. Then there wasn't much to tempt us but okay enough places to eat, so we paid the €21 for a cab to Deia, where

Robert Graves had lived.

Clambered our way to the top of the small, pretty town in the smattering of rain, but couldn't spot him in the graveyard. We found his widow, Beryl, who'd only died in 2003, and wondered whether Graves' grave was somewhere else. The Dr teased me that we'd be able to hear it if we were near; the spinning his response to

what I've done to his myths.

So instead we made our way back down the road to his house - now a little museum. We had about half an hour before the one bus back to Soller, so not loads of time to look round. But the keen girl on the gate took us into the garage to watch a short film full of BBC archive material and narrated as if by Graves himself. It was a bit harsh on

Laura Riding, but didn't avoid discussing Graves' complicated love life. And dammit, his grave

was up in that little church but we didn't have time to go back.

We crossed through the neat garden of orange trees and into his simple house. There was his writing room, there the printing press that got him arrested and deported at the start of the Civil War. The Dr was surprised by the volume of communist literature in Beryl's study - and wondered how Graves could have been welcomed back to Mallorca after World War Two, for thirty years under Franco.

She also felt that if one day our home is opened up to my legion of disciples, she'll leave special instruction not to leave it so tidy. Visitors will have to step over my discarded underpants and around the stacks of papers and mess.

The bus was 15 minutes late, and we were anxious we'd miss the last train back to Palma. We were even more anxious that the double-decker bus might survive the winding, mountainous roads. And then we failed to notice our stop and had five minutes of panic in Porte de Soller before getting back on the same bus which was heading back the way it had come. We were in Soller again in time for a beer and a sandwich, and to buy some home made white chocolate. Then the Dr slept on the train back to Palma and I read two-thirds of The Man Who Would Be King on her Sony e-reader.

We nosed through the dark, atmospheric city looking for places to eat. It was a Monday so most places seemed closed, or perhaps we were just in the wrong area.

We followed our earlier footsteps back to the cathedral, hoping we'd find somewhere, and if not we'd get a taxi. The cathedral loomed beautifully in the quiet darkness and we stopped to take pictures. But our tummies were grumbly.

But still there was nothing open. We passed down through government offices, sporting this sign which I thought was funny. "Bombers" means "firemen" rather than "terrorists".

After that, we found a brilliant place called Forn des Teatre on Pza Weyler for wine and tapas. There was gambas in plenty of garlic, and bocquerones and local cheeses and meat. Then a taxi back to our villa. As we pulled up into the resort complex, we felt slightly uneasy. The hotel is lavish and luxuriant, but it could almost be anywhere, a gated suburb outside of the real world. It seemed to have no connection with any of the history or people we'd seen that day. And on balance we'd have been happier living in a small town like Deia than this anonymous place...

So we were a little hesitant as we made our way next morning to the all-important pitch. The nice bloke was there and fixed us coffees, and explained that "timeshare" has a lot of negative connotations, so Marriott has worked up a flexible system with all kinds of options. He talked through them, but it was obvious pretty quickly that none of it was quite right for us. Neither of us really value holidays where you

don't do anything.

It was all very genial, and it makes you feel quite adult to be there at all. But I felt a little like we'd been spotted as frauds or children. Afterwards, we went to the spa, and I wondered about the other people there. Did they all sign up to villas? Did they come back here every year?

I could see it would be good if you had young children to have a regular escape. Or if you liked golf, or wanted somewhere to retire too... There's comfort in the recognisable brand of the hotel chain and the high standards of customer service. But it's not just for us.

That night we drank in the hotel bar, enjoying lavish measures of gin. I'd not taken any work with me on purpose, but had made some notes for something I want to pitch someone, and was already thinking about getting back to work. At the moment it's called "Machine code", but I will not speak more of it just yet.

I guess a resort like this is great if you want to get away from the real world, to escape the tedium of work. I can see how you'd judge your success in a job by how much time you can get away. But again, it's not us. I miss writing when I away.

Tuesday looked grey as we packed our bags and I finished

Pashazade. We checked out and got the taxi to the

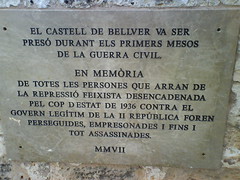

Castell de Bellver, overlooking Palma.

It took a bit of time to find our way in 'cos the taxi driver had directed us to a locked door. But then we were into a top-quality castle, with all kinds of clever defences. There were moats within moats and round walls to resist undermining, bridges across that had kinks in them, and other cunning ways to impede access. Inside there were exhibits of Roman sculpture and casts, which greatly pleased the Dr.

We wandered around for a couple of hours quite happily, and then had an easy lunch before cabbing it to the airport and wending our way home.