For my forthcoming book on 1967 Doctor Who story The Evil of the Daleks, I undertook some especially nerdy investigation.

Of the seven episodes of the story, only episode 2 exists in the BBC archive, but from the other six episodes there are a total of 414 off-air photographs (that is, taken of the story playing out on a screen, rather than on set during production). There are four main sources of these images:

1. THE SEQUENCE OF THE OFF-AIR IMAGES

We know the order in which to view the tele-snaps because they were printed in strips, and we know the order of Chris Thompson's images because the negatives still exist - again, in strips - so it's easy to follow the sequence. But how do we work out the order when we put both sets of images together?

A useful aid is the camera scripts - that is, the scripts detailing how the cameras should cover the action, as used in the studio recording of the episodes. The camera scripts for this story are included on the CD soundtrack in the box-set Doctor Who: The Lost TV Episodes - Collection Four.

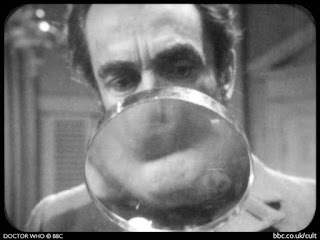

As an example, scene 4 of episode 1 is set in the study of an antique shop and according to the camera script began with a tracked-out close-up shot of Waterfield through a magnifying glass.

A tele-snap shows this, the magnifying glass filling the middle of the lower half of the frame, obscuring Waterfield’s mouth and nose as we look at him face on:

The script says there was then a knock on the door, and the camera was to elevate and track out as Waterfield went to answer it, providing the first establishing shot of the room. That’s what we see in the first of Chris Thompson’s images: a wide shot of the room full of antiques, Waterfield with his back to us as he bends to unlock the double doors in the centre of frame:

We can see Waterfield from head to toe, but with his back to us it’s not clear from this image – as it is in the script – that he’s wearing Victorian clothes. Note that the dialogue in the scene doesn’t refer to what he is wearing: it’s a visual clue to him being out of his own time, bolstered by Waterfield’s later, spoken, mix-up over guineas and pounds.

The next tele-snap is from a moment later: the same camera position but with the door now open. Waterfield has stepped back and to the right, and is in profile as he faces Keith Perry:

The next tele-snap is a close two-shot of Perry and Waterfield as Perry admires an antique that’s apparently just off the left-hand edge of frame. The camera script says this is a clock on Waterfield’s desk, but Waterfield’s desk is later visible on the other side of the room. The dialogue doesn’t say ‘clock’, so Perry might be admiring something else.

Thompson’s next photograph shows Perry in roughly the same position, but Waterfield some distance behind him, on the other side of his desk:

This is almost identical to the next tele-snap, except Perry is bent a little lower to examine whatever antique is just out of shot, and Waterfield is slightly further left behind the desk – the suggestion being that after the previous tele-snap he moved right, off the edge of frame, and then came into shot again behind the desk.

Again, the next of Thompson’s images is almost identical to the next tele-snap, looking down on Perry as he seems to admire the room’s chandelier, and it’s difficult to tell which of the two images comes first. So we need another clue...

The last of Thompson’s images from this scene still has Perry gazing upwards at the chandelier, but we can also see Waterfield standing behind his desk. Since that suggests the camera has pulled back and to the left since the previous two images, we can perhaps work out the order by comparing the position of the leg of Waterfield’s desk to Perry’s shoulder. In the tele-snap, the leg is some distance from Perry; in Thompson’s similar image, Perry’s arm just obscures the very end of the leg; in Thompson’s next image the leg is completely behind him. So, watch the position of the table leg adjacent to Perry's arm:

2. HOW MUCH THE SURVIVING EPISODE 2 HAS BEEN CROPPED

When The Evil of the Daleks was made, the episodes were recorded on two-inch videotape. None of those original recordings survive, but a copy of episode 2 made on 16mm film is held by the BBC, and was used for the commerical releases on VHS and DVD.

To make a 16mm copy from the two-inch videotape in the first place, a film camera was positioned in front of a screen on to which the episode was played from the tape. As Richard Molesworth explains in his brilliant book, Wiped! Doctor Who’s Missing Episodes (Second Edition), ‘the 16mm film recordings were slightly zoomed in ... to ensure that the edges of the screen were never captured’ (pp. 273-4). This means that the existing 16mm episode is a slightly cropped version of the original. Can the off-air photographs tell us how much has been cropped?

Here are two comparisons from the beginning of episode 2, in which a character called Kennedy is cornered by a Dalek.

In this second comparison, we can see more of the upper-most hexagon on the panel behind Kennedy than we can in the episode:

Overall, it’s about 2% from the top and about 1% of the bottom from the total height of the tele-snaps. But when I put this to Steve Roberts, of the Doctor Who Restoration Team which prepared the episode for DVD, he said that:

3. ANIMATING THE OFF-AIR IMAGES

Lastly, in several cases, two separate off-air images are almost identical - some where John Cura took two "tele-snaps" in very quick succession, and other where two photographers happened to capture the same instant.

But that means we can return something of the missing story to life:

Thanks to Simon Belcher for technical brilliance, Tom Spilsbury and Peter Ware at Doctor Who Magazine and Richard Bignell at Nothing at the End of the Lane for sharing images, and Steve Roberts for his patience in untangling my muddled thinking.

Of the seven episodes of the story, only episode 2 exists in the BBC archive, but from the other six episodes there are a total of 414 off-air photographs (that is, taken of the story playing out on a screen, rather than on set during production). There are four main sources of these images:

- 383 "tele-snaps" taken by John Cura - most of them published as a "photonovel" on the BBC Doctor Who website, and in Doctor Who Magazine's special, The Missing Episodes - The Second Doctor Volume Two

- 26 photographs from episode 1 taken by the story's designer, Chris Thompson and published in issue three of fanzine Nothing at the End of the Lane in 2012

- 2 photographs from episode 4 and 1 photograph from episode 5 taken by fan Terry Reason, published in Doctor Who Magazine #200 in 1993, and again in Nothing at the End of the Lane #3.

- 2 photographs from episode 5 taken by fan Gordon Lengden and now in the posession of Tony Clark, again published in Nothing at the End of the Lane #3

1. THE SEQUENCE OF THE OFF-AIR IMAGES

We know the order in which to view the tele-snaps because they were printed in strips, and we know the order of Chris Thompson's images because the negatives still exist - again, in strips - so it's easy to follow the sequence. But how do we work out the order when we put both sets of images together?

A useful aid is the camera scripts - that is, the scripts detailing how the cameras should cover the action, as used in the studio recording of the episodes. The camera scripts for this story are included on the CD soundtrack in the box-set Doctor Who: The Lost TV Episodes - Collection Four.

As an example, scene 4 of episode 1 is set in the study of an antique shop and according to the camera script began with a tracked-out close-up shot of Waterfield through a magnifying glass.

A tele-snap shows this, the magnifying glass filling the middle of the lower half of the frame, obscuring Waterfield’s mouth and nose as we look at him face on:

The script says there was then a knock on the door, and the camera was to elevate and track out as Waterfield went to answer it, providing the first establishing shot of the room. That’s what we see in the first of Chris Thompson’s images: a wide shot of the room full of antiques, Waterfield with his back to us as he bends to unlock the double doors in the centre of frame:

We can see Waterfield from head to toe, but with his back to us it’s not clear from this image – as it is in the script – that he’s wearing Victorian clothes. Note that the dialogue in the scene doesn’t refer to what he is wearing: it’s a visual clue to him being out of his own time, bolstered by Waterfield’s later, spoken, mix-up over guineas and pounds.

The next tele-snap is from a moment later: the same camera position but with the door now open. Waterfield has stepped back and to the right, and is in profile as he faces Keith Perry:

The next tele-snap is a close two-shot of Perry and Waterfield as Perry admires an antique that’s apparently just off the left-hand edge of frame. The camera script says this is a clock on Waterfield’s desk, but Waterfield’s desk is later visible on the other side of the room. The dialogue doesn’t say ‘clock’, so Perry might be admiring something else.

Thompson’s next photograph shows Perry in roughly the same position, but Waterfield some distance behind him, on the other side of his desk:

This is almost identical to the next tele-snap, except Perry is bent a little lower to examine whatever antique is just out of shot, and Waterfield is slightly further left behind the desk – the suggestion being that after the previous tele-snap he moved right, off the edge of frame, and then came into shot again behind the desk.

Again, the next of Thompson’s images is almost identical to the next tele-snap, looking down on Perry as he seems to admire the room’s chandelier, and it’s difficult to tell which of the two images comes first. So we need another clue...

The last of Thompson’s images from this scene still has Perry gazing upwards at the chandelier, but we can also see Waterfield standing behind his desk. Since that suggests the camera has pulled back and to the left since the previous two images, we can perhaps work out the order by comparing the position of the leg of Waterfield’s desk to Perry’s shoulder. In the tele-snap, the leg is some distance from Perry; in Thompson’s similar image, Perry’s arm just obscures the very end of the leg; in Thompson’s next image the leg is completely behind him. So, watch the position of the table leg adjacent to Perry's arm:

2. HOW MUCH THE SURVIVING EPISODE 2 HAS BEEN CROPPED

When The Evil of the Daleks was made, the episodes were recorded on two-inch videotape. None of those original recordings survive, but a copy of episode 2 made on 16mm film is held by the BBC, and was used for the commerical releases on VHS and DVD.

To make a 16mm copy from the two-inch videotape in the first place, a film camera was positioned in front of a screen on to which the episode was played from the tape. As Richard Molesworth explains in his brilliant book, Wiped! Doctor Who’s Missing Episodes (Second Edition), ‘the 16mm film recordings were slightly zoomed in ... to ensure that the edges of the screen were never captured’ (pp. 273-4). This means that the existing 16mm episode is a slightly cropped version of the original. Can the off-air photographs tell us how much has been cropped?

Here are two comparisons from the beginning of episode 2, in which a character called Kennedy is cornered by a Dalek.

- Top left: a screengrab from the repeat of this sequence in 1968 story The Wheel in Space episode 6 - where it's shown on the TARDIS scanner screen.

- Top right: a screengrab from episode 2 of The Evil of the Daleks, as featured on the Lost in Time DVD box set.

- Bottom left: John Cura's tele-snap, care of Doctor Who Magazine.

- Bottom right: John Cura's tele-snap, care of the photonovel on the BBC Doctor Who website.

In this second comparison, we can see more of the upper-most hexagon on the panel behind Kennedy than we can in the episode:

Overall, it’s about 2% from the top and about 1% of the bottom from the total height of the tele-snaps. But when I put this to Steve Roberts, of the Doctor Who Restoration Team which prepared the episode for DVD, he said that:

"The amount of image crop in a film recording is variable. Mostly you’ll find that there is more cropped from the top than the bottom – as demonstrated in your comparisons ... The film recorder camera had to ideally pull-down the next frame – pulling out the registration pins, accelerating it from stationary, decelerating it back to stationary and putting in the registration pins again – in the 1.6 milliseconds of video field blanking. This was extremely difficult and in practice it wasn’t actually possible to do it, which would result in distortion at the top of the image as the first few lines were being recorded to film as the film was still settling to stationary. To avoid this distorted area being seen on subsequent projection, the film recorder would blank the first few lines of the picture so that they were never recorded to film.So the existing episode is missing material from the top and bottom of the frame, but we can’t be sure how much is missing, and some of it might have been missing on the original two-inch videotape.

There are so many variables. Cura’s monitor would be over-scanned too, there would be some overscan and blanking in the film recorded as discussed and there’s always some overscan at the telecine stage – where film recorded on location is played into the studio recording of the episode – to avoid the ragged edges of picture appearing in the video frame."

3. ANIMATING THE OFF-AIR IMAGES

Lastly, in several cases, two separate off-air images are almost identical - some where John Cura took two "tele-snaps" in very quick succession, and other where two photographers happened to capture the same instant.

But that means we can return something of the missing story to life:

Thanks to Simon Belcher for technical brilliance, Tom Spilsbury and Peter Ware at Doctor Who Magazine and Richard Bignell at Nothing at the End of the Lane for sharing images, and Steve Roberts for his patience in untangling my muddled thinking.

No comments:

Post a Comment