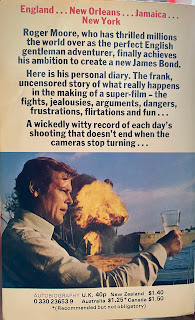

On 14 October - Day 2 of shooting - Moore turned 45, the age I am now. There's a lot here about his aches and pains, his need of dental work, the various therapies employed and it's odd to think of myself, old and broken as I am, in better fettle than Bond. There's also his anxieties and homesickness, and all the business that goes alongside making the movie itself.

"Daily more of the mechanics behind the mystique that is Bond become clear. The actual shooting, the rapport between my countenance and the camera, forms only a fraction of a field of operations which is a constant source of surprise." (Day 10, p. 27.)

The extra-curricular work includes endless press interviews, Moore is increasingly impatient when asked the same question each time: how will his Bond be different from Sean Connery's? There are endless photoshoots, appearances, charity galas, bits and pieces. Then there's the pop concert he goes to, where its announced to the audience that the new Bond is in their midst - and no one seems to care. He's self-effacing about this, and often very funny.

Yet Moore's wife Luisa is annoyed by how much this all encroaches into time he could spend with his children. Then there's the awkwardness of his various love scenes: how Luisa treats him on the days he's got sex on the schedule, the etiquette of what you say to the other actor during and after this stuff. It's Moore's diary, his version of events, but I often found myself wondering how it was for them.

There's lots, too, that is amazing to see in an official, licensed release. In that sense, the book reminds me of Alan Arnold's absolutely extraordinary Once Upon a Galaxy: A Journal of the Making of The Empire Strikes Back which I now want to read again. Moore is candid about other actors fluffing their lines, mucking up shots or weeping. He cites various mistakes made by producer Harry Saltzman (such as, on page 32, making the wrong call on what the weather would be like, and so losing a day's shooting). There's stuff about Moore's children, such as his son needing an enema for trapped wind, that is personal, embarrassing and hardly relevant to the making of the film. But Moore seems to delight in this kind of thing: the gulf between movie fantasy and prosaic reality.

I wonder how much the cast and crew really enjoyed his constant pranking, which sometimes seems a bit cruel. I'm surprised, too, how little the other producer, Cubby Broccoli, features. Is that because he wasn't on set, or because he kept out of Moore's way, or because Moore had nothing funny or scathing to say about him, or because he knew better than to do so? Again, that's what make this so intriguing: Moore is sometimes brutally candid but we're not getting the whole story.

As early as day 5 we're told of plans afoot for the next Bond film, The Man With the Golden Gun, to begin shooting 18 months later in August 1974, and we really feel the weight and power of the Bond machine. But there's little on how much of a risk this all was, Moore the second attempt to keep the franchise going with a new leading man after George Lazenby had not turned out as hoped.

"The build-up of publicity and advertising for the film is fascinating. I was asking Harry [Saltzman] about the sort of money the Bonds have made in the past and he told me the biggest grosser was Thunderball which has done 64 million dollars to date. Diamonds are Forever, the last before Live and Let Die, had already grossed 48 million and it is only on its first time round [the cinemas]. OHMSS was the lowest and even that grossed 25 million dollars. I just hope ours will be as successful." (Day 52, p. 132.)

There's little sense he felt under pressure, I think because he could see the script and production were all good. But I wonder how Saltzman and Broccoli were feeling, especially given other tensions in the air. This is a film tapping into something of its moment. For example, early on, Moore was horrified to hear Saltzman shouting the N-word on set.

"He was not trying to start a race riot but simply calling to our English props man [by the] nickname he has answered to since the days of silent cinema. I pointed out that it might be better to to find him another name here in the racial hotbed of Louisiana so we have settled on 'Chalky'. As Bond, I make love to Rose Carver, played by beautiful black actress, Gloria Hendry, and Luisa has learned from certain Louisiana ladies that if there is a scene like that they won't go to see the picture. I personally don't give a damn and it makes me all the more determined to play the scene." (Day 11, p. 31.)

There was more on this the following day:

"Paul [Rabiger, supervising make-up] agrees with Guy [Hamilton, director], Tom Mankiewicz [writer] and myself that it would have been more interesting if Solitaire, our present leading lady, had been black as she was in Tom's original screen play, but United Artists would not stand for it." (Day 12, p. 33.)

A few days later, Moore reports on an argument on set, the black stunt team having objected to scenes being shot with white stunt performers blacked up (Day 17, p. 44). Two days after this, yet another photocall was the cause of further disagreement when Yaphet Kotto - the actor playing the villainous Mr Big - raised his fist in a black power salute.

"Whether he was serious or not I don't know but the sequel was a scorching row. [Publicity director] Derek Coyte pointed out that the pictures would rouse resentment from the rabid whites and could be seen as an endorsement of black power by militant blacks. We are making anything but a political picture but Derek said the photographs syndicated far and wide would involve us in a controversy which could do nothing but harm. Yaphet was incensed. At midday he and the black stunt men lunched together and during the afternoon Derek Coyte was ostracised by blacks who had previously been pally." (Day 19, p. 50.)

The next day, the black stuntmen were airing their grievances on local TV (p. 51). And these tensions were not confined to Louisiana. Returning to the UK, Moore shares a letter sent to him by a woman from North Wales, outraged by the sight of him pictured with Gloria Hendry as seen in the Daily Express (Day 54, p. 136).

Moore is unapologetic. It strikes me that George Lazenby had seen Bond as reactionary, but there's something here of Bond as progressive, just as they've tried to push things in the recent Daniel Craig films. Hardly perfect, but attempting to steer the juggernaut.

I think there's something in that, too, when Moore first hears the theme tune for the film. In Goldfinger, Bond mocks the Beatles. Now a Beatle has written his title song, and Moore's response is telling:

"It is a tremendous piece of music and I will stick my neck out and say that three weeks from its release it will be number one in the charts. It's not last year's music, it's not even this year's music, it's next year's." (Day 66, p. 154.)