The house is at least 100 years old, possibly late 19th century. And there in the original brickwork are the paw prints of a cat. We're going to leave them on show.

The blog of writer and producer Simon Guerrier

AAAGH! celebrate's Doctor Who's 48th birthday today in a bit of silliness written by me and illustrated by Brian Williamson. Doctor Who Adventures #244 is still in shops for another day, and includes a whole bunch of old-skool stuff, including mention of Koquillion.

AAAGH! celebrate's Doctor Who's 48th birthday today in a bit of silliness written by me and illustrated by Brian Williamson. Doctor Who Adventures #244 is still in shops for another day, and includes a whole bunch of old-skool stuff, including mention of Koquillion.

"'Then he went out into the rain and there were three old ladies under an umbrella who had heard he was there and gave him a cheer.'"Many of the lively characters Matthew speaks of - and spoke to - have died, and as he argues the Second World War is now passing out of living memory. This chance to capture and record these fleeting ghosts before they are fully gone is utterly compelling.Philip Murphy, Alan Lennox-Boyd: A Biography (1999), quoted in Matthew Sweet, The West End Front, p. 286.

Dream the myth onwardsThanks to editor Anthony S Burdge and Anne Petty at Kitsune Books for permission to post it here. I landed the Doctor in ancient Greece in my book, The Slitheen Excursion - where he met what might be the real people who inspired the myths of Athena, Noah and the Medusa, amongst others.

Simon Guerrier

Do stories matter if we know they're not true?

That seems to be central to the idea of myth. They are stories that matter. Ken Dowden, in his book The Uses of Greek Mythology, argues that “myths are believed, but not in the same way that history is”(1). If they were true they would be history. But stories still illuminate the truth.

The father of psychoanalysis certainly thought so. Sigmund Freud used the stories of ancient mythology to illuminate aspects of the human condition. Most famously, he named a group of unconscious and repressed desires after the mythical king of Thebes, Oedipus.

The story of Oedipus has been retold since at least the 5th Century BC. By linking to it, Freud suggested that the desires he'd uncovered were not new or localised. They were universal.

Freud was clearly fascinated by myth. His former home in London – now a museum – contains nearly 2,000 antiquities illustrating myths from the Near East, Egypt, Greece, Rome and China, many lined up on the desk where he worked. He argued that psychoanalysis could be applied to more than just a patient's dreams, but to “products of ethnic imagination such as myths and fairy tales” (2).

But, as Dowden points out, you can only psychoanalyse where there is a psyche. Who are we analysing when we probe ancient myths – which have been retold for thousands of years? Do we examine a myth as the dream of an original, single author, or of the culture that author belonged to? Dowden argues that “psychoanalytic interpretation of myth can only work if it reveals prevalent, or even universal, deep concerns of a larger cultural group”(3).

He also quotes Carl Jung, who developed the idea of the “collective unconscious”, a series of archetypal images that we all share in the preconscious psyche and which, as a result, appear regularly in our myths. Jung warned against efforts to interpret the meanings of these images: “the most we can do is dream the myth onwards and give it a modern dress”(4).

That seems to me what Doctor Who does, retelling old stories in new ways, surprising us with the familiar. The archetypes of Doctor Who – the invasion, the base under siege, the person taken over by an alien force, regeneration – have been embedded for decades. Yet the series keeps finding new ways to present them, and new perspectives and insights along the way.

That's also true of this book, probing the Doctor's adventures for new perspectives and insights. The essays contained here don't take Doctor Who as the dream of one single author whose unconscious desires can now be exposed. Instead, it probes our shared mythology as Doctor Who fans – of which the TV show is just a part – to explore our own cultural unconscious.

“Myth” means many things in this book. It's any fiction with a ring of truth. It's any story with cultural of psychological value. It's any work with staying power, whose themes and ideas are still relevant generations after the first telling. It's the established, fictional history of characters and worlds, the “continuity” so often complex and contradictory. It's the moment at which a character becomes a hero or even a god. It's anything we want it to be.

And that is why it's so revealing.

(1) Dowden, Ken, The Uses of Greek Mythology, London: Routledge 2000 [1992], p. 3.

(2) Freud, Sigmund, Totem and Taboo, Leipzig and Vienna: 1913, English translation ed. J Strachey London 1955. Cited in Dowden, p. 30.

(3) Dowden, p. 31

(4) Jung, Carl and Kerényi, C, Science of Mythology: Essays on the myth of the divine child and the mysteries of Eleusis, 1949, English translation, cited in Dowden, p. 32

“Please note that sometimes gay characters die in fiction because in fiction sometimes people die (this is particularly true of soldiers at war, where Sitch Sexuality and Anyone Can Die are both common tropes); this isn't an if-then correlation, and it's not always meant to "teach us something" or indicative of some prejudice on the part of the creator - particularly if it was written after 1960. The problem isn't when gay characters are killed off: the problem is when gay characters are killed off far more often than straight characters, or when they're killed off because they are gay. This trope therefore won't apply to a series where anyone can die (and does).”“Anyone can die (and does)” is a good summary of the era of Doctor Who in which The First Wave is set. By “era”, I mean Season Three – not, as you argue, the First Doctor's adventures as a whole. In that season, Katarina and Sara die, Anne Chaplet (a sort-of companion in The Massacre) is apparently killed, Vicki is written out during a bloody battle that leaves Steven badly wounded, and Dodo vanishes off-screen having had her brain scrambled.

Another AAAGH! from Doctor Who Adventures #243 - in shops till yesterday. This one features Jabe the tree from The End of the World and the Minotaur from The God Complex. (Sadly excised to make it all fit was the First Doctor in vest and shorts on a treadmill muttering that "*Puff!* This old body's wearing a bit thin. *Pant!*")

Another AAAGH! from Doctor Who Adventures #243 - in shops till yesterday. This one features Jabe the tree from The End of the World and the Minotaur from The God Complex. (Sadly excised to make it all fit was the First Doctor in vest and shorts on a treadmill muttering that "*Puff!* This old body's wearing a bit thin. *Pant!*") Doctor Who: The Anachronauts stars Jean Marsh and Peter Purves, directed by Ken Bentley. Cover by Iain Robertson.

Doctor Who: The Anachronauts stars Jean Marsh and Peter Purves, directed by Ken Bentley. Cover by Iain Robertson.

Cleaning Up won Best Thriller at the Aesthetica Short Film Festival this weekend. Brother Tom and I had an amazing time in York, seeing loads of the 150 short films shown, comparing notes with lots of spectacularly talented film-makers and wannabe film-makers, and generally larking about. As a result of all the nattering, we've realised how much we've learned by making our film – and stolen from all the clever people we've worked with.

Cleaning Up won Best Thriller at the Aesthetica Short Film Festival this weekend. Brother Tom and I had an amazing time in York, seeing loads of the 150 short films shown, comparing notes with lots of spectacularly talented film-makers and wannabe film-makers, and generally larking about. As a result of all the nattering, we've realised how much we've learned by making our film – and stolen from all the clever people we've worked with.I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word;James Joyce then used it in Ulysees. But is that all that it means? In 1910, Sir Edwin Lawrence-Durning pointed out that it's also an anagram “Hi ludi, F. Baconis nati, tuiti orbi”, or “These plays, F. Bacon’s offspring, are preserved for the world” - which Sir Edwin argued showed Shakespeare's plays were written by Francis Bacon.

for thou art not so long by the head as

honorificabilitudinitatibus: thou art easier

swallowed than a flap-dragon.

"Avon goes undercover on a research base… in the guise of an advanced android."The other stories released alongside mine are by Peter Anghelides and Nigel Fairs. Gareth Thomas is also returning to the series as Blake, and it's been announced that Anthony Howells and nice Beth Chalmers will be in it, too. There will be more Blake's 7 CDs later in 2012 - and books as well. So that's all a bit exciting.

The Dr spotted these sneaky Weeping Angels in Kensal Green cemetery, London. There's a TARDIS-shaped gap in the midst of them, which can surely be no coincidence. Empirical proof that Doctor Who is real.

The Dr spotted these sneaky Weeping Angels in Kensal Green cemetery, London. There's a TARDIS-shaped gap in the midst of them, which can surely be no coincidence. Empirical proof that Doctor Who is real.

Another AAAGH!, this one from Doctor Who Adventures #238, published a few days after The Wedding of River Song.

Another AAAGH!, this one from Doctor Who Adventures #238, published a few days after The Wedding of River Song. Here's the Crab nebula - or M1 in Messier's catalogue. It's an exploded star, and Chinese astronomers reported seeing the supernova in 1054 AD. At it's heart there's a small, very dense neutron star. I thought the tendrils of gas looked a bit like the insides of a heart.

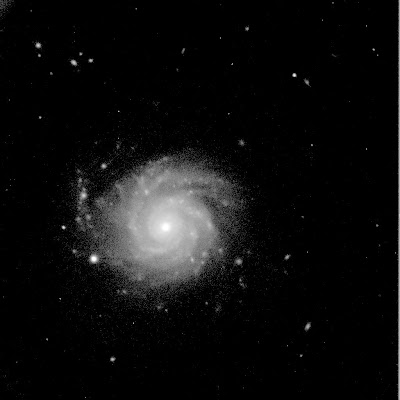

Here's the Crab nebula - or M1 in Messier's catalogue. It's an exploded star, and Chinese astronomers reported seeing the supernova in 1054 AD. At it's heart there's a small, very dense neutron star. I thought the tendrils of gas looked a bit like the insides of a heart. The galaxy NGC 2776 is a lot less famous - or studied - than M1. It's a spiral galaxy in the constellation of Lynx, which appears disc-on to us.

The galaxy NGC 2776 is a lot less famous - or studied - than M1. It's a spiral galaxy in the constellation of Lynx, which appears disc-on to us.

Another AAAGH!, this time from Doctor Who Adventures issues #237, published just a few days after the episode Closing Time, where the Doctor battled Cybermats in a department store.

Another AAAGH!, this time from Doctor Who Adventures issues #237, published just a few days after the episode Closing Time, where the Doctor battled Cybermats in a department store.Doctor Who – The Age of Heroes

Simon Guerrier

27 March 2008

June is 17 and not very confident about her forthcoming A-levels. She’s on a college trip to the Palace of Westminster (not, she has learnt that morning, the “Houses of Parliament”) when she spots the Doctor. He must be important because he doesn’t have a security pass – not even the pastel-coloured stickers that they give to the tourists – and yet the policemen with machine guns let him go where he likes.

June dares to follow him and saves his life when a monster jumps out on him. The Doctor stops the monster by talking nonsense. It feeds on nonsense and illogic – so the Palace is like a restaurant. The Doctor owes June a favour and she asks if he can help with her essay. She’s got to write about the history of democracy.

Chapter 1

The Doctor says he knows a thing or two about history. Seeing history live – touching it, smelling it, getting your fingers dirty – is more exciting than dusty old books. But as they set the coordinates for the golden age of ancient Athens, he picks up a signal from an alien spaceship that’s got into trouble. They’re going to have to make a quick detour.

They arrive in Athens, 1687 AD. The Venetians are at war with the Turks. There’s a Turkish garrison in the temple up on the rock overlooking the town – the Parthenon is pretty much complete and looking good for its 2,000 years. For a brief moment June and the Doctor are separated and June realises she could be stranded in the primitive past. There’s something odd about the war though; both sides accusing the other of using strange and magical weapons.

The Doctor and June are reunited. They get away from the fighting Turks and Venetians and investigate the distress signal. They soon discover a party of Slitheen.

Chapter 2

But it emerges that they’re not there to muck up the war. They just want to keep everyone away from a grotto of stalactites and stalagmites which they’re using for some nefarious purpose.

The Slitheen are, though, fascinated by the Doctor and June – who must, they think, be using some kind of warp-core technology to journey back in time. And even schoolkids know that warp-cores are dangerously unstable. So the Doctor finds himself arrested as a dangerous maniac, when that’s what he normally accuses the Slitheen of.

June helps the Doctor escape, but rather than running away the Doctor insists they find out what the Slitheen are up to. It turns out the stalactites are calcified Slitheen – these Slitheen’s ancestors who were on Earth thousands of years ago.

Chapter 3

As they get older, Slitheen suffer from hardening of their soft tissues – a bit like we suffer from hardening of the arteries. They slowly lose the moisture inside themselves, and mineral deposits build up until they can’t move. The early affects are like Calciphylaxis, with brittle skin etc. And then they harden out entirely and become like statues.

At first the Doctor assumes it is some kind of rescue operation. But the young Slitheen want to know what happened to all the loot they never inherited. When the older Slitheen won’t tell them, they throw tantrums and blow things up.

Chapter 4

The Doctor has to intercede. The Slitheen spaceship, hidden on the top of the Acropolis, explodes. This blows up the Parthenon – history will assume the Venetians did it.

Chapter 5

The ancient Slitheen will not survive long. But they recognise the Doctor and June, having met them thousands of years before. They’re dying, and realise the Doctor hasn’t met them yet. They say he’ll understand what happened to the loot when he goes back to meet them. And they die. June is upset by this, and the Doctor admits he’s not used to feeling sorry for Slitheen. They’re a very strange family.

But now it seems he and June have to go back in time to meet these Slitheen in the first place.

The Doctor looks through history for the Slitheen signals. He finds them – roughly the same place but about 3,000 years before. And that’s worrying because mankind is quite impressionable back then. Sophisticated, space-faring aliens mucking around with the ancient Greeks could do terrible things to the development of human history.

Having landed in about 1,500 BC, the Doctor does a scan for aliens. And there are nearly 2,000 of them in the area. They step out into a world where aliens are living amongst the humans quite openly. Spaceships and high technology can be seen everywhere.

Chapter 6

There’s a great tourist industry running to the place, all kinds of aliens getting to mix with humanity when it hasn’t even sussed out basic architectural stuff like the arch. These aliens aren’t changing history. They’ve always been there – they’re the Gods and monsters of Ancient Myth.

At first it seems fun, but June is horrified by how the aliens pretend to be Gods to the locals. And some aliens are very badly behaved, frying the humans with laser guns just for a bit of a laugh.

The Doctor just runs off. June tries to stop some aliens picking on the humans. The aliens turn on her. She is going to be fried.

Chapter 7

The Doctor arrives dragging some Slitheen with him, insisting he and his friend didn’t pay for their tickets expecting to get fried. He waves his psychic paper around and people assume he’s a tourist, too. And the Slitheen intercede: it’s not done to fry fellow holiday-makers.

June recognises these Slitheen. The ancient Slitheen they met in 1687 turn out to be running the tourism. They are young and sprightly hucksters, and don’t take kindly to the Doctor and June interfering.

They invite the Doctor and June back to their office for a glass of something to make up for the inconvenience. The Doctor is keen to find out more of what they’re up to so agrees to go along. On the way, the Slitheen explain the terrible complexities of this project – how they use accelerators to grow food very fast to feed the demands of the tourists, how the bookings system keeps breaking down… all the rigours of a small business.

But the invitation to drinks is really a trap. The Slitheen know psychic paper when they see it. And they assume the Doctor is some kind of anti-time-travel protestor, and the one who has been causing all the earthquakes. For the sake of saving humanity, the Slitheen will now execute him and June.

Chapter 8

The Doctor and June escape death at the hands of the Slitheen when a half-man, half-snake called Cecrops comes to complain about how some of the other tourists are treating the locals. The Slitheen insist they’ve got a contract with the local kings that strictly agrees the terms of tourists’ behaviour.

Humans are to be respected. The Doctor uses this point of law to get himself and June released. The Slitheen get very nervous the moment anyone mentions lawyers.

Cecrops is very embarrassed about the tourist trade. He is a real humanophile, though his enthusiasm for how the little ape people slowly puzzle out problems doesn’t go down very well with June who finds him patronising.

The Doctor asks about these anti-time-travel protests, which people assume are some sort of politically correct statement that humans should be left alone to develop. Cecrops explains that he’s got problems with that ethos, too – the humans’ lives are nasty, brutal and short. June is surprised to discover she would be considered in late middle-age by being 17.

But anyway, Cecrops hasn’t seen and sabotage. He’s seen natural phenonema – earthquakes and things. It’s just the earthquakes have been really bad recently. And, as if on cue, there’s a terrible earthquake.

Chapter 9

The Doctor, June and Cecrops try to help people. But the Doctor insists this isn’t any ordinary earthquake. It’s a warp shift; the side effect of unstable warp core technology. June remembers the seventeenth-century Slitheen saying even children knew that was dangerous.

They investigate. Yes, the Slitheen here are using some dodgily acquired warp core technology to bring their tourists here. And they’ve been greedy; the system is exhausted and sagging at the edges. There are earthquakes and other strange phenomena. The Doctor tries to fix things, but the Slitheen catch him and it’s them trying to stop him that pulls the plug on everything. There’s not an explosion; instead the whole world seems to be falling apart.

Chapter 10

A widescreen disaster movie. The huge explosion causes a massive flood right across the Mediterranean. As described in the Greek legend of Deucalion, the rivers swell over the coastal plains and engulf the foothills, washing everything clean (the legend might also be the same route as that of Noah and Utnapishtim, but we’ll skirt round saying so explicitly). From the Acropolis they watch the great tidal wave coming in, and thousands are killed.

(I’ll probably expand this action stuff; have June separated from the Doctor and having to be a bit of a heroine. Have the Slitheen show that, though they’re greedy and dangerous, they don’t actually mean any harm.)

Chapter 11

The floods pass; the climate and timeline just diffusing the kinks in the system. The warp core technology is wrecked so all the alien holiday makers who’ve survived now find that they are stranded. Facing this mob, and the thought of insurance claims etc., the surviving Slitheen throw themselves off the Acropolis into the receding waters – ostensibly to their deaths.

June can’t believe they wouldn’t have had an emergency escape plan, and the Doctor is delighted. He leads the aliens to the cave where, in 2,000 years, there’ll be Slitheen-shaped stalagmites. There is a small vortex pod hidden at the back of the cave. The Doctor messes with its dimensions until it’s big enough to carry everyone.

But Cecrops is one of a few aliens who want to stay. If they don’t help clear up some of this mess, he says, the humans here are all going to die.

Chapter 12

June is suspicious of the Doctor – he seems happy to let the aliens believe that if they don’t take the vortex pod they’ll be stranded here forever. Why won’t he mention the TARDIS? But she has come to know him and she supposes he must have a good reason. Anyway, it looks like the aliens could do these humans some good.

Cecrops adopts the daughters of the dead Athenian king Actaeus. (In legend, the half-man, half-fish Cecrops, first King of Athens, taught the Athenians marriage, reading, writing and ceremonial burial.)

But with the waters all round the Acropolis, how are humans going to survive? The Doctor uses his sonic screwdriver to draw water from the rocks – a spring of not very pleasant-tasting water, but water all the same. And June has seen how the Slitheen provided food for the tourists. She points their accelerator at the rock and up springs an olive tree. It’s not quite what she had in mind to feed everybody, but the olives will serve as an appetizer. (This makes the Doctor Poseidon and June Athene, I think.)

There’s a party later that evening. It looks like things are going to work out. With the loss of the aliens and creatures, a new age begins. One not of Gods and monsters but of extraordinary human beings. The age of heroes.

But the Doctor is still not content. He’s not sure history is quite on course as it should be. And anyway he promised June he’d show her real democracy at work.

Chapter 13

The TARDIS arrives in 480 BC to see the Parthenon being built and the golden age of Athens in full swing. June is appalled to discover that 17 is still considered quite old here. And that women aren’t going to get the vote until 1952 AD.

The Doctor and June soon get separated, but June has learnt a lot in her adventures thus far and is okay now to explore on her own. It seems the Gods and monsters are remembered as legends. But the town isn’t known as Athens – it’s called Cecropia.

She thinks the Doctor will make for the Acropolis to see the building work going on. And she’s curious to see the view of Cecropia up there. At first the male builders don’t see what business it is of hers, but their old, fat foreman seems pleased by June’s interest and offers to show her around.

But as soon as they’re on their own, the fat old man unzips his forehead. Creaky and old folk, it’s the last of the huckstering Slitheen – stranded on Earth for 1,000 years.

Chapter 14

The Slitheen have been hidden on Earth for 1,000 years. They had tried to get rescued at first, and then they’d seen the difference Cecrops was making with the primitive humans. They helped out – not pushing them or inventing anything for them, but getting them to write things down so the things humans learnt could be passed on. They’ve got people telling stories, sharing ideas.

And it’s hard work because humans keep having wars and things. The Parthenon is being built on the ruins of a previous one razed to the ground just a few years ago. And the Slitheen are running out of time. They’re calcifying, becoming the stalagmites June has seen in the future. If they could reach their people there are possible cures, but they’re just going to dry out.

June knows it has to be like this because she’s seen what happens. But the Slitheen are glad to have played their part, to have written themselves into history even if no one will ever know. They’re glad that June knows.

She leaves the grotto of dying Slitheen to find the Doctor waiting for her. He left her to discover the truth for herself – just as the aliens had let humans develop their own way. Now the lesson is over and its time for June to go back home.

The Doctor takes her back to the Palace of Westminster the same moment that she left. But she’s a different person now; better and wiser for what she’s seen.

Only when the Doctor’s gone does she realise she can’t use any of what she’s seen in her essay. She hurries off to rejoin her college mates.