Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Free to those who can afford it

Free stuff! Issue 5 of Big Finish's Vortex magazine is now available for free. Pages 14-15 feature my diary of writing Dr Who & the Drowned World and include a fetching picture of me by the western-most fountain in Trafalgar Square. Readers will have no interest in knowing that I am wearing the same brown tee-shirt as I write these words now...

There's plenty of other excitements in the issue too, including interviews with authors of Dr Who & the Company of Friends, in which m'colleague Jonny Morris explains how he wrote the Doctor's new companion - Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. The Dr might even be swayed by a story in which Dr Who meets Lord Byron.

And how thrilling to see the Inside Story included in the release schedule. It is so almost real!

Also free - yes, free - is m'colleague Caleb's latest Podcast of Impossible Things, which this time reviews the Big Finish Short Trips range. As I blogged before, I owe a lot to those books which gave me my first professional break. The podcast includes a competition to win the last of the anthologies, Dr Who & the Indefinable Magic, which has one of my stories in it.

There's plenty of other excitements in the issue too, including interviews with authors of Dr Who & the Company of Friends, in which m'colleague Jonny Morris explains how he wrote the Doctor's new companion - Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. The Dr might even be swayed by a story in which Dr Who meets Lord Byron.

And how thrilling to see the Inside Story included in the release schedule. It is so almost real!

Also free - yes, free - is m'colleague Caleb's latest Podcast of Impossible Things, which this time reviews the Big Finish Short Trips range. As I blogged before, I owe a lot to those books which gave me my first professional break. The podcast includes a competition to win the last of the anthologies, Dr Who & the Indefinable Magic, which has one of my stories in it.

Labels:

big finish,

droo,

freebies,

htdcml,

m'colleagues,

stuff written

Monday, June 29, 2009

Inside out!

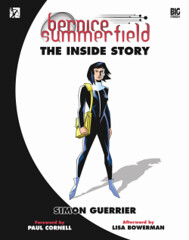

Big Finish have announced that my book, Bernice Summerfield - The Inside Story, will be out in August. Pre-order it NOW and get your copy signed by me and Lisa Bowerman.

Big Finish have announced that my book, Bernice Summerfield - The Inside Story, will be out in August. Pre-order it NOW and get your copy signed by me and Lisa Bowerman.I've been working on the thing since 2005, so its a great relief and excitement to send it off be published. Kudos to Alex Mallinson, whose design work is utterly splendid. And thanks to everyone who helped to make it happen.

Professor Bernice Surprise Summerfield (2540- ) made her debut at the end of September 1992 in the pages of Doctor Who Magazine #192. The issue included a two-page prelude by Paul Cornell for his original novel, Love and War:

Benny swung her satchel into her tent, and took a deep breath of the morning air. She was pretty, in a sharp sort of way, as Clive had often realised but never quite got round to expressing. Short black hair cut so that strands of it hung over her brow, emphasising her mobile eyebrows and ironic eyes. Her mouth could purse in self-mockery, but there was something about the curve of it that rather hurt. English hurt, like there were things she’d rather not talk about.

Love and War was published two weeks’ later on Thursday 15 October. That same issue of Doctor Who Magazine also included Cornell’s notes on the character and Gary Russell’s glowing review of the novel. ‘Miss it at your peril!’ he enthused. ‘Probably the most mature and intelligent of the run [of New Adventures novels] so far.’

‘Benny looks set to make a refreshing and interesting companion to this darker Doctor,’ he said of the new companion. ‘So long as other writers cope with her as well as Cornell has - and the indications are that they have - I think Bernice could soon become as popular as Ace.’

So how was Bernice created? And how has she changed in the years since that debut?

The Inside Story talks to those involved in her development. Find out how she came to be, how she was developed and where she’s going next. See the stories that almost-got-told, and listen in on the creative battles, personality clashes and very, very bad jokes.

With exclusive access to more than 100 writers, editors, producers and illustrators, it’s as wild, exciting and unlikely a journey as any Benny has made herself.

Includes a Foreword by Benny’s creator, Paul Cornell, and an Afterword by Lisa Bowerman, who plays Benny in the Big Finish audio dramas.

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Long playing

So. Turned 33 on Wednesday: the same age as Jesus when the Romans killed him, and (if my sums are right) the age of David Tennant when he was cast as Doctor Who.

(Of no interest to anyone, but Peter Davison became a former Doctor Who a month before turning 33. So I'm now older than two Doctors, as old as one, with another eight still to catch up.)

Derren Brown's Enigma show was superb. I have some theories about how some of his tricks might have worked, and also about the imagery and associations he uses. But I'll hold off until I've read his Tricks of the Mind, which a kind person got me for my birthday.

Did splendidly well for loot, too: all of The Wire, The Deadly Assassin (I concede all Mr Gillatt says in his recent DWM review, and yet I still love this story), Party Animals, Vonnegut's A Man Without A Country, a duvet, some pants, a long-sleeved tee-shirt, various London bus maps from different years in the last century and a cheesecake.

But mostly I have been working on things as-yet unannounced. One thing Paul Cornell speaks of should get an official announcement next week, and I've pretty much finished my bits of it. Then there's rewrites today, and a script to be written for the CBBC competition which closes on Wednesday. And rewrites on another spec script, thanks to the kind diligence of L. And I'm awaiting notes on something else. And a “go” on a couple of other big things, too...

In the meantime, Danny Stack has set up an official site and trailer for Origin, the short film he wrote and directed on which I was a runner and associate producer. It stars Lee Ross (Kenny in Press Gang) and Katy Carmichael (Twist in Spaced) – both of whom I served murky tea.

Oh, and my Primeval novel has also just had a glowing 9 out of 10 review:

(Of no interest to anyone, but Peter Davison became a former Doctor Who a month before turning 33. So I'm now older than two Doctors, as old as one, with another eight still to catch up.)

Derren Brown's Enigma show was superb. I have some theories about how some of his tricks might have worked, and also about the imagery and associations he uses. But I'll hold off until I've read his Tricks of the Mind, which a kind person got me for my birthday.

Did splendidly well for loot, too: all of The Wire, The Deadly Assassin (I concede all Mr Gillatt says in his recent DWM review, and yet I still love this story), Party Animals, Vonnegut's A Man Without A Country, a duvet, some pants, a long-sleeved tee-shirt, various London bus maps from different years in the last century and a cheesecake.

But mostly I have been working on things as-yet unannounced. One thing Paul Cornell speaks of should get an official announcement next week, and I've pretty much finished my bits of it. Then there's rewrites today, and a script to be written for the CBBC competition which closes on Wednesday. And rewrites on another spec script, thanks to the kind diligence of L. And I'm awaiting notes on something else. And a “go” on a couple of other big things, too...

In the meantime, Danny Stack has set up an official site and trailer for Origin, the short film he wrote and directed on which I was a runner and associate producer. It stars Lee Ross (Kenny in Press Gang) and Katy Carmichael (Twist in Spaced) – both of whom I served murky tea.

Oh, and my Primeval novel has also just had a glowing 9 out of 10 review:

“Author Simon Guerrier manages to stuff 231 pages with way more action, adventure and twists than I thought possible ... He writes short, punchy chapters which flip between the characters so quickly - with an endless supply of cliff-hangers - that you are constantly on the edge of your seat as the twists and turns are thrown at you ... This could be the most enjoyable book you purchase this year.”(I seem to have lost a point for using the new team at the ARC.)Nick Smithson, Book Review – Primeval: Fire and Water, Sci-fi-Online.

Labels:

bisy,

dinosaurs,

film,

paul cornell,

spooky,

stuff written,

things as-yet unannounced

Monday, June 22, 2009

The Dust Run and The Trial

Amazon now list my two forthcoming Blake's 7 audio plays: The Dust Run and The Trial. The two half-hour episodes will be on one CD out in the autumn (Amazon says November).

Jenna Stannis (Carrie Dobro) is a convicted smuggler when she runs into the dissident Roj Blake. She's a spacer, too hardly set foot on a planet. Which is why sending her for life on Cygnus Alpha is such an appalling verdict. How did it go so wrong?Got to see an early version of Lee Thompson's splendid cover this weekend. And there's more details about the range - including Jan Chappell's return as Cally - on the Blake's 7 website.

The Dust Run

Jenna. Stannis has grown up as a spacer, where the normal rules don't apply. No school, no police, no public imperatives; that's still all to come. But the situation on Earth is changing and the effects are slowly being felt throughout the Vega system. It's going to mean trouble for a brash boy called Veldan who Jenna doesn't fancy at all.

Soon Jenna and Veldan are competing in the Dust Run racing shuttles through an asteroid field without using computers, making the complex calculations in their heads. Its dangerous, fool-hardy and really good fun. But they re playing for the highest of stakes...

The Trial

The election is going to change everything. A man called Roj Blake promises the voters new hope, an end to years of corruption. There are those who can't let him be heard. But Jenna Stannis is determined to get his message out to the stars.

It's been years since the Dust Run and Jenna's a changed woman. She's left the Vega system far behind, using her excellent piloting skills to carve out a life as a smuggler. Blake's message could earn her a fortune.

Friday, June 19, 2009

Red eye, yellow eye

It’s all been a bit hectic here, but the two mountains of work are in (I just need to finish an index – something I’ve not written before). Was up till 2 am Wednesday getting through a draft of something, but I’m really rather pleased with how it’s come out. Announcements in due course.

But cor, blimey I am tired. Taking the weekend off to go to a party in Cardiff.

And then yesterday I spent the afternoon in A&E waiting to have my eye looked at. Something got into my left eyeball on Wednesday, and no amount of blinking, blubbing or washing would shift it. Knackered by all the typing, it meant I then couldn’t sleep. And yesterday my eye was all bloodshot.

So I sat in a hot, noisy hospital waiting room, hoping I wouldn’t miss the shout of my name. Read my way through some very exciting paperwork relating to a possible new bit of work, and then 50 pages of China Mieville’s new book, The City and The City.

Only half-way through but it’s an extraordinary book. A police procedural set in eastern Europe in two co-existing cities. Think the two spaceships blended together in the Doctor Who story Nightmare on Eden, only without the Muppets. Only citizens in either city must not notice their counterparts on fear of invoking Breach.

Mieville’s writing is punchy and vivid, making this mad idea chillingly real. It also reads like it’s a translation, and all kinds of little details – the proximity of Budapest, mentions of films and books, the bafflement of visiting Canadians – helps give it a ring of truth. The Wire as written by Borges, so far.

(I must get round to writing up notes on other good recent reads: gobsmack-o-wowed by David Kynaston’s Austerity Britain, loved the first two-thirds of Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s Arabesk trilogy, and, despite reservations about the terrible jokes, John O’Farrell’s Utterly Impartial History of Britain is fun, too.

And speaking of recommendations, have loved the first season of 30 Rock and am slowly getting through the first season of the Twilight Zone, the Up series and The Monocled Mutineer.)

Anyway. Eventually a nice doctor prodded and poked my eye, using brown-orange dye to spot the problem. Think it’s sorted now, though it isn’t half still blinking sore. And I spent the rest of yesterday looking like half of me was off to a disco.

Plenty of typing still awaits my attention the far side of Cardiff, so might not be here all that much.

Plenty of typing still awaits my attention the far side of Cardiff, so might not be here all that much.

Oh, and hooray for the BBC Archive, who have been loading up yet more goodies in the last few weeks. Today they’re marking the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11 landing on the Moon with a whole load of marvellous moon porn, including some exclusive interviews with three Apollo astronauts.

But cor, blimey I am tired. Taking the weekend off to go to a party in Cardiff.

And then yesterday I spent the afternoon in A&E waiting to have my eye looked at. Something got into my left eyeball on Wednesday, and no amount of blinking, blubbing or washing would shift it. Knackered by all the typing, it meant I then couldn’t sleep. And yesterday my eye was all bloodshot.

So I sat in a hot, noisy hospital waiting room, hoping I wouldn’t miss the shout of my name. Read my way through some very exciting paperwork relating to a possible new bit of work, and then 50 pages of China Mieville’s new book, The City and The City.

Only half-way through but it’s an extraordinary book. A police procedural set in eastern Europe in two co-existing cities. Think the two spaceships blended together in the Doctor Who story Nightmare on Eden, only without the Muppets. Only citizens in either city must not notice their counterparts on fear of invoking Breach.

Mieville’s writing is punchy and vivid, making this mad idea chillingly real. It also reads like it’s a translation, and all kinds of little details – the proximity of Budapest, mentions of films and books, the bafflement of visiting Canadians – helps give it a ring of truth. The Wire as written by Borges, so far.

(I must get round to writing up notes on other good recent reads: gobsmack-o-wowed by David Kynaston’s Austerity Britain, loved the first two-thirds of Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s Arabesk trilogy, and, despite reservations about the terrible jokes, John O’Farrell’s Utterly Impartial History of Britain is fun, too.

And speaking of recommendations, have loved the first season of 30 Rock and am slowly getting through the first season of the Twilight Zone, the Up series and The Monocled Mutineer.)

Anyway. Eventually a nice doctor prodded and poked my eye, using brown-orange dye to spot the problem. Think it’s sorted now, though it isn’t half still blinking sore. And I spent the rest of yesterday looking like half of me was off to a disco.

Plenty of typing still awaits my attention the far side of Cardiff, so might not be here all that much.

Plenty of typing still awaits my attention the far side of Cardiff, so might not be here all that much. Oh, and hooray for the BBC Archive, who have been loading up yet more goodies in the last few weeks. Today they’re marking the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11 landing on the Moon with a whole load of marvellous moon porn, including some exclusive interviews with three Apollo astronauts.

Tuesday, June 16, 2009

A riot of colour

"The Parthenon took a bit of getting used to. June and the Doctor boggled in front of the enormous temple, in the spot where future tourists would one day pose for photos. The roof and columns and all of it had been brightly painted in red and yellow and blue. The statues wore gaudy make-up, their bare skin brilliantly pink."Science is catching up with Doctor Who, sort of. Jo Marchant reports on evidence that the Parthenon's sculptures were bright blue.Me, Doctor Who and the Slitheen Excursion, p. 221.

Monday, June 15, 2009

Perspectives on the human condition - for kids!

Dashed away from working full pelt on two as-yet-unannounced mountains of work to attend the BBC Writersroom's Q&A with new head of CBBC Drama Steven Andrew and writer Ellie Brewer. There's a competition to write a new drama script for 8-12s with a deadline of 1 July. Hope to get something in there once I'm past my two current mountains.

Sat with a good throng of other wannabes in the Royal Court Theatre. There were clips of MI High, Roman Mysteries and Sarah Jane - the latter from an episode by one Joseph Lidster. I wonder whatever became of him?

Kids' telly is a simple brief: expanding the imagination with unmissable storytelling, offering new perspectives on life and vivid sensations the kids will remember for ever.

While kids' drama needs to be be from the perspective of kids, they also can't be in every scene because of the restrictions on child actors. So you need adults, and also adults-only scenes, and enough kids to vary up schedules. Kids also can tend to have more days off sick than adults, so you need some flexibility for last-minute re-writes.

Keep kids' dialogue short, too: the actors need to remember it, and they need to be able to say it. In fact many of the clips we saw had very little dialogue - several minutes of material all told entirely visually.

But most of my notes are about specific things in the idea I've already got. So I'm not going to share those here, at least not now.

Didn't stay long after, but said hello to Jason Arnopp, then dashed home to the waiting mountains. Missed the storm by a whisker.

ETA: Transcript of the talk here.

Sat with a good throng of other wannabes in the Royal Court Theatre. There were clips of MI High, Roman Mysteries and Sarah Jane - the latter from an episode by one Joseph Lidster. I wonder whatever became of him?

Kids' telly is a simple brief: expanding the imagination with unmissable storytelling, offering new perspectives on life and vivid sensations the kids will remember for ever.

While kids' drama needs to be be from the perspective of kids, they also can't be in every scene because of the restrictions on child actors. So you need adults, and also adults-only scenes, and enough kids to vary up schedules. Kids also can tend to have more days off sick than adults, so you need some flexibility for last-minute re-writes.

Keep kids' dialogue short, too: the actors need to remember it, and they need to be able to say it. In fact many of the clips we saw had very little dialogue - several minutes of material all told entirely visually.

But most of my notes are about specific things in the idea I've already got. So I'm not going to share those here, at least not now.

Didn't stay long after, but said hello to Jason Arnopp, then dashed home to the waiting mountains. Missed the storm by a whisker.

ETA: Transcript of the talk here.

Thursday, June 11, 2009

The naked and the dead

Finished Naked, the second half of the autobiography by former Doctor Who girl Anneke Wills (I blogged part one in October 2007). It picks up with Anneke now 30, stuck in a one-sided marriage in a nice house in Norfolk, with her two young kids.

As before, it’s a breathless, wide-eyed account of events, even the worst of it told with little bitterness. At the end, she describes writing the thing as “a meditation in letting go.” There’s an awful lot to be rid of: the callous way her husband (actor Michael Gough) only gets close to her just before he leaves for good. There’s the more and more common deaths of loved ones, most especially the shock of her daughter, Polly, being killed in a car crash. And there’s her decades-long following of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, where, as “Anita” or “Neet”, she seems to have spent her time wearing red and orange and doing the most menial jobs.

This spiritualist stuff takes up a lot of the book – Bhagwan’s teachings, the advice of ghosts, the drugs and song lyrics of the time. Groog, I thought: it’s going to be a hippy ex-actress wittering on about crystals for 30 years. But Anneke’s abrupt honesty about her own experiences are often fascinating. We get her fears and her contradictions – for all the humility imposed by Bhagwan’s teaching she’s still very much into her groovy clothes, while the free love enjoyed by her fellas leaves her raging and insecure.

Then there are her observations about the burgeoning power politics around her cult leader. In the US, for example, this man of peace is surrounded by guards with machine guns. There’s a bullying cook who keeps Champagne and chocolates to herself, and the horror amongst devotees when Anneke’s boyfriend wears colours of the wrong rank. For all these people are apparently seeking to transcend the crude matter of being, they are bound by the mundane. Funny how this quest to be more of an “individual” means conforming to the same clothes and rituals. There’s the same gossip, infighting and scandal as any community.

While Anneke is often surrounded by like-minded, hippy friends, a lot of her relationships seem hard work. She admits she’s attracted to difficult men, and her main loves all leave her for younger women. She’s on good terms with her son and on better terms with her mother than in the first volume, though it’s difficult to share her empathy for the pain felt by her ex-husband and the father who left her when she was a child. For all her spiritual retreats and courses and reading, Anneke is still bent under a great burden of guilt. She is not quite the free spirit she claims.

There’s a constant sense of yearning as she travels round the world, as if she’s struggling to escape from under this terrible weight. The death of her daughter comes at just the moment she seems to be sorting things out for herself, and the grief casts an awfully long shadow.

Of course, the book seems primarily aimed at Doctor Who fans, though Anneke’s time in the series was dealt with in volume one. The series crops up at regular intervals, for the most part when she’s surprised to be recognised for the part she played so long ago. Then she’s “rediscovered” by the fan community in the early 1990s and describes the excitement and generosity of conventions. She’s got notes to give on each of the Doctors – including Eccleston’s performance onscreen, as he's the only one she’s not met. For the rest, its tiny insights into them as actors, real people. There’s climbing Sydney Harbour Bridge with Colin Baker, a drunk Sylvester McCoy playing the spoons against a bouncer, and her response to Paul McGann:

Especially at the end I found myself reading between the lines: for “independent” you might read “difficult”; for “single-minded”, “pain in the arse”. I cringed when at a convention she rants about a first draft of a script while its author (one of my chums) is in the audience. For all the peace-and-love stuff, that's the kind of thing that'd make me want to curl up and die.

But the appeal of the book is its matter-of-fact honesty, and she's unflinching about all she's done. There’s her periods and pooping, drugs and experimental sex mixed in with thoughts on music and films. It proclaims, “This is me; this is all I am. You can think what you like.”

And it’s that, ultimately, that makes Anneke’s life story such a joy.

As before, it’s a breathless, wide-eyed account of events, even the worst of it told with little bitterness. At the end, she describes writing the thing as “a meditation in letting go.” There’s an awful lot to be rid of: the callous way her husband (actor Michael Gough) only gets close to her just before he leaves for good. There’s the more and more common deaths of loved ones, most especially the shock of her daughter, Polly, being killed in a car crash. And there’s her decades-long following of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, where, as “Anita” or “Neet”, she seems to have spent her time wearing red and orange and doing the most menial jobs.

This spiritualist stuff takes up a lot of the book – Bhagwan’s teachings, the advice of ghosts, the drugs and song lyrics of the time. Groog, I thought: it’s going to be a hippy ex-actress wittering on about crystals for 30 years. But Anneke’s abrupt honesty about her own experiences are often fascinating. We get her fears and her contradictions – for all the humility imposed by Bhagwan’s teaching she’s still very much into her groovy clothes, while the free love enjoyed by her fellas leaves her raging and insecure.

Then there are her observations about the burgeoning power politics around her cult leader. In the US, for example, this man of peace is surrounded by guards with machine guns. There’s a bullying cook who keeps Champagne and chocolates to herself, and the horror amongst devotees when Anneke’s boyfriend wears colours of the wrong rank. For all these people are apparently seeking to transcend the crude matter of being, they are bound by the mundane. Funny how this quest to be more of an “individual” means conforming to the same clothes and rituals. There’s the same gossip, infighting and scandal as any community.

While Anneke is often surrounded by like-minded, hippy friends, a lot of her relationships seem hard work. She admits she’s attracted to difficult men, and her main loves all leave her for younger women. She’s on good terms with her son and on better terms with her mother than in the first volume, though it’s difficult to share her empathy for the pain felt by her ex-husband and the father who left her when she was a child. For all her spiritual retreats and courses and reading, Anneke is still bent under a great burden of guilt. She is not quite the free spirit she claims.

There’s a constant sense of yearning as she travels round the world, as if she’s struggling to escape from under this terrible weight. The death of her daughter comes at just the moment she seems to be sorting things out for herself, and the grief casts an awfully long shadow.

Of course, the book seems primarily aimed at Doctor Who fans, though Anneke’s time in the series was dealt with in volume one. The series crops up at regular intervals, for the most part when she’s surprised to be recognised for the part she played so long ago. Then she’s “rediscovered” by the fan community in the early 1990s and describes the excitement and generosity of conventions. She’s got notes to give on each of the Doctors – including Eccleston’s performance onscreen, as he's the only one she’s not met. For the rest, its tiny insights into them as actors, real people. There’s climbing Sydney Harbour Bridge with Colin Baker, a drunk Sylvester McCoy playing the spoons against a bouncer, and her response to Paul McGann:

“I fancied him. He’s beautiful, and shy, and real. If only I was twenty years younger…”It’s a bit weird to hear her natter about mutual friends (especially in the same paragraph as she mentions Jim Broadbent), and even events I was at myself. But this isn’t a book about “us”, the fans. Nor is about the famous people Anneke has met. It’s about her coming to terms with herself.Anneke Wills, Naked, pp. 27-8.

Especially at the end I found myself reading between the lines: for “independent” you might read “difficult”; for “single-minded”, “pain in the arse”. I cringed when at a convention she rants about a first draft of a script while its author (one of my chums) is in the audience. For all the peace-and-love stuff, that's the kind of thing that'd make me want to curl up and die.

But the appeal of the book is its matter-of-fact honesty, and she's unflinching about all she's done. There’s her periods and pooping, drugs and experimental sex mixed in with thoughts on music and films. It proclaims, “This is me; this is all I am. You can think what you like.”

And it’s that, ultimately, that makes Anneke’s life story such a joy.

Monday, June 08, 2009

Things Exploding 2: Everything’s Exploding!

For research purposes, obviously, the Dr and I went on a date to see Night at the Museum 2. Spent most of the weekend proofing 310 pages of a new book, with the film ticking through the back of my brain. Here are some too-serious thoughts.

It should really be “Night at the Museums”, as night-watchman Ben Stiller leaves the American Museum of Natural History in New York for the Smithsonian in Washington DC – which, he reminds us, is really 19 museums arranged round a lawn (and, in the movie, sharing underground vaults). Though the National Gallery of Art isn’t part of the Smithsonian. And also Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” is in the Chicago Art Institute. But hush. It’s only a movie.

It’s a fun and funny movie, with a massive cast it struggles to fully accommodate. Much of the cast of the first film spends most of this one stuck in a crate. Then there are weird cameos – a couple of would-be villains from other franchises, and a scene with the Smithsonian’s own guard. Both are funny at first but just go on and on…

There are some great comic moments and absurd characters and performances, but I kept feeling it was a rough draft, everything in the script filmed and edited into order before the judicious pruning.

The film is full of incongruous, odd things: a love interest who can’t be a love interest because she’s a museum object; Stiller leaving his son – so crucial to the first film – home alone in another city while he jets off to have this adventure…

A Doctor Who episode like Love & Monsters makes a virtue of the strange incongruity of real life; here everything’s put neatly back in the box. In the final scene, the awkward love interest gets swapped for a real woman played by the same actress (no mention of the artefact-woman flying off stiff-lipped to her death).

And it’s really talkie. Like American football, as soon as there’s a bit of action and excitement, it stops to discuss it in depth. There is much tedious guff about the brilliance of America – and obviously no mention of the cultural imperialism implicit in the museums’ display of precious objects from all round the world. What’s the provenance, say, of this ancient Egyptian portal to Hell?

For all the moral is Stiller realising the nobility of his vocation in guarding these artefacts, the ending depends on a big brawl where a whole load of old stuff gets trashed. The Dr watched in horror – at one point, as the first ever airplane smashed into a huge cabinet of precious things, she even grabbed my hand.

At the end, the museum is bustling with thrilled and interested public from a cross-section of demographic groups – a museum’s happy ending. But what does the mannequin Theodore Roosevelt offer that his (evil) computer hologram version didn’t? He tells the kids the years he was born and died, and we see he rode a horse… The hologram’s just the same, but you don’t need to stay up late to see it.

The museums’ presidents and cowboys get to offer stoic wisdom, but it never really suggests why museums might be important or worth preserving. The artefacts here are only of interest because they come to life.

It should really be “Night at the Museums”, as night-watchman Ben Stiller leaves the American Museum of Natural History in New York for the Smithsonian in Washington DC – which, he reminds us, is really 19 museums arranged round a lawn (and, in the movie, sharing underground vaults). Though the National Gallery of Art isn’t part of the Smithsonian. And also Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” is in the Chicago Art Institute. But hush. It’s only a movie.

It’s a fun and funny movie, with a massive cast it struggles to fully accommodate. Much of the cast of the first film spends most of this one stuck in a crate. Then there are weird cameos – a couple of would-be villains from other franchises, and a scene with the Smithsonian’s own guard. Both are funny at first but just go on and on…

There are some great comic moments and absurd characters and performances, but I kept feeling it was a rough draft, everything in the script filmed and edited into order before the judicious pruning.

The film is full of incongruous, odd things: a love interest who can’t be a love interest because she’s a museum object; Stiller leaving his son – so crucial to the first film – home alone in another city while he jets off to have this adventure…

A Doctor Who episode like Love & Monsters makes a virtue of the strange incongruity of real life; here everything’s put neatly back in the box. In the final scene, the awkward love interest gets swapped for a real woman played by the same actress (no mention of the artefact-woman flying off stiff-lipped to her death).

And it’s really talkie. Like American football, as soon as there’s a bit of action and excitement, it stops to discuss it in depth. There is much tedious guff about the brilliance of America – and obviously no mention of the cultural imperialism implicit in the museums’ display of precious objects from all round the world. What’s the provenance, say, of this ancient Egyptian portal to Hell?

For all the moral is Stiller realising the nobility of his vocation in guarding these artefacts, the ending depends on a big brawl where a whole load of old stuff gets trashed. The Dr watched in horror – at one point, as the first ever airplane smashed into a huge cabinet of precious things, she even grabbed my hand.

At the end, the museum is bustling with thrilled and interested public from a cross-section of demographic groups – a museum’s happy ending. But what does the mannequin Theodore Roosevelt offer that his (evil) computer hologram version didn’t? He tells the kids the years he was born and died, and we see he rode a horse… The hologram’s just the same, but you don’t need to stay up late to see it.

The museums’ presidents and cowboys get to offer stoic wisdom, but it never really suggests why museums might be important or worth preserving. The artefacts here are only of interest because they come to life.

Friday, June 05, 2009

The basic unsuitability of Orwell’s voice

Just a week after their superb Big Ben celebration, the BBC Archive has published a whole load of documents about George Orwell's employment at the BBC during World War Two. For two years (1941-43) he was Talks Producer for the Eastern Service - writing propaganda for broadcast to India.

There's a full page about the archive collection in today's Times, and John Humphreys spoke to Jean Seaton - the BBC's official historian - about it on this morning's Today. With weird brilliance, you can watch that segment of radio.

Much of the attention is on "the basic unsuitability of Orwell’s voice." I'm sad to learn no recordings of his voice survive, which is why this is such a revelation (and why he's not on the excellent BBC/British Library Spoken Word - British Writers CD). Seaton speculated why his voice was not suitable: Orwell was shot in the throat during the Spanish Civil War (an experience he described as "very interesting" in Homage to Catalonia) and also suffered from TB.

I'm more interested in the internal memo from the splendidly titled "Director of Empire Services" describing Orwell himself and his suitability for a job with the Beeb.

There's a full page about the archive collection in today's Times, and John Humphreys spoke to Jean Seaton - the BBC's official historian - about it on this morning's Today. With weird brilliance, you can watch that segment of radio.

Much of the attention is on "the basic unsuitability of Orwell’s voice." I'm sad to learn no recordings of his voice survive, which is why this is such a revelation (and why he's not on the excellent BBC/British Library Spoken Word - British Writers CD). Seaton speculated why his voice was not suitable: Orwell was shot in the throat during the Spanish Civil War (an experience he described as "very interesting" in Homage to Catalonia) and also suffered from TB.

I'm more interested in the internal memo from the splendidly titled "Director of Empire Services" describing Orwell himself and his suitability for a job with the Beeb.

"I was much impressed by him. He is shy in manner but extremely frank and honest in his interview. He has held strong Left Wing opinions and actually fought for the Republican Government in Spain. He is of opinion that that may be held against him, though when I questioned him closely about his loyalties and the danger of finding himself at odds with policy, his answers were impressive. He accepts absolutely the need for propaganda to be directed by the Government and stressed his view that in war-time discipline in the execution of Government policy was essential."There's his reference and appraisal, letters from Orwell setting out his stall, and - two years after getting the job - his resignation. Having thanked the BBC for their "generosity" and allowing him "the greatest latitude", he says

"for some time past I have been conscious that I was wasting my own time and the public money on doing work that produces no result. I believe that in the present political situation the broadcasting of British propaganda to India is an almost hopeless task."There's then some correspondence from his time on the remote Isle of Jura - where he was writing 1984. It includes a gem of a pitch for a programme:

"I don't know much about Darwin's later life. What about a defence of Pontius Pilate, or an imaginary conversation between P.P. and, say, Lenin (one could hardly make it J.C.)"I'm still avidly following the blog of Orwell's diaries, where, three months before the outbreak of war, he's currently busy in the garden. In his Essays, Orwell described

“The outstanding, unmistakable mark of Dickens’s writing is the unnecessary detail."And that's what makes the archive and blog so outstanding. These unnecessary details bring the man whose voice is lost to us so vividly to life.Orwell, “Charles Dickens”, Essays, pp. 68-9.

Tuesday, June 02, 2009

Prints of Persia

Spent the weekend typing things as-yet unannounced (two of which I’ve now delivered), then yesterday afternoon saw some sunshine and the Shah ‘Abbas exhibition at the British Museum (until 14 June).

It’s the latest in the BM’s shows on ‘great rulers’ – following on from China’s first Emperor and Hadrian, with Moctezuma to come in the autumn. This seems a less block-busting show than those last two; it was certainly pretty empty yesterday, which meant I could actually get a look at all the exhibits and didn’t have to queue to read any captions. Out of the sunshine and crowds, the dark reading room gave the exhibition a reverent air. A visitor just ahead of me respectfully bowed before each beautifully bound Qu’ran on display; I tried not to make any sound as I followed in my vulgar shorts and flip-flops.

Perhaps the quiet is because the shah or Iran are not such a draw, or it’s because the show lacks any must-see exhibits. There were a lot of faded old rugs and examples of calligraphy, plus examples of Iranian trade: coins and silks from Europe, illustrations from India, crockery from China. Though these were interesting in themselves, there was nothing with particular wow factor. (The Dr also noted that comparatively few of the exhibits came from the museum’s own collections.)

That said, where (as I blogged in December), the BM’s Babylon exhibition,

Shah ‘Abbas promoted Mashhad as a rival place of pilgrimage to Mecca (he expanded Iran’s borders during his reign, but not quite that far). The exhibition was good at explaining the political context of the shah’s reign, too. He established Shi’a Islam as the country’s state religion – which it remains to this day. Yet his reign, says the exhibition guide, was also,

There’s a small amount on science towards the end of the exhibition. As the caption says,

Perhaps the most interesting item in the whole exhibition, though, is one small, innocuous image of the shah with a caption that doesn’t quite spell-out what it seems to be showing. We know it’s the shah from his tell-tale huge moustache (he apparently set a fashion). The image, painted by Muhammad Qasim in 1627 and on loan from the Louvre, has the shah sitting rather close to a long-sideburned page boy. The caption translates the Arabic text: it’s a romantic poem.

Perhaps the most interesting item in the whole exhibition, though, is one small, innocuous image of the shah with a caption that doesn’t quite spell-out what it seems to be showing. We know it’s the shah from his tell-tale huge moustache (he apparently set a fashion). The image, painted by Muhammad Qasim in 1627 and on loan from the Louvre, has the shah sitting rather close to a long-sideburned page boy. The caption translates the Arabic text: it’s a romantic poem.

This, we’re told, is from a picture album for the shah’s own private enjoyment. It includes the impression of a royal seal, suggesting it’s not propaganda. The Hadrian exhibition had a whole section on pretty boy Antinous – though left him out its family guide. Whatever the purpose or origin of the image here, and though the exhibition frames the picture with a discussion of the succession, it's odd the reference to the Shah's sexuality is only implicit.

It’s the latest in the BM’s shows on ‘great rulers’ – following on from China’s first Emperor and Hadrian, with Moctezuma to come in the autumn. This seems a less block-busting show than those last two; it was certainly pretty empty yesterday, which meant I could actually get a look at all the exhibits and didn’t have to queue to read any captions. Out of the sunshine and crowds, the dark reading room gave the exhibition a reverent air. A visitor just ahead of me respectfully bowed before each beautifully bound Qu’ran on display; I tried not to make any sound as I followed in my vulgar shorts and flip-flops.

Perhaps the quiet is because the shah or Iran are not such a draw, or it’s because the show lacks any must-see exhibits. There were a lot of faded old rugs and examples of calligraphy, plus examples of Iranian trade: coins and silks from Europe, illustrations from India, crockery from China. Though these were interesting in themselves, there was nothing with particular wow factor. (The Dr also noted that comparatively few of the exhibits came from the museum’s own collections.)

That said, where (as I blogged in December), the BM’s Babylon exhibition,

“struggle[d] to convey the scale of the Biblical city, squeezed as it is into the upstairs of the old Reading Room,”there’s a much better sense here of the world these artefacts come from. At the centre of the exhibition were projected huge photos the mosque of Shaykh Lutfullah in his capital, Isfahan, and the shrine of Imam Riza in Mashhad. As so often, I was stunned by the Arabic script worked so beautifully into the plaster – a sign that the workmen were literate.

Shah ‘Abbas promoted Mashhad as a rival place of pilgrimage to Mecca (he expanded Iran’s borders during his reign, but not quite that far). The exhibition was good at explaining the political context of the shah’s reign, too. He established Shi’a Islam as the country’s state religion – which it remains to this day. Yet his reign, says the exhibition guide, was also,

“notable as a period of religious tolerance in Iran – a privilege extended to Armenian Christians, Jews and others.”It nicely dovetailed the context with English history, as an early caption explained:

“Shah ‘Abbas, like his contemporary Elizabeth I, inherited an unstable country that had recently redefined its religion and was surrounded by powerful enemies.”Known in English as “the Sophy”, Shah ‘Abbas is mentioned in Twelfth Night and the Merchant of Venice. Reigning from 1587 to 1629, he overlapped with the first two Stewart kings. Yet the Iranian monarchy had very different ideas about the succession – the English monarchs might have bumped off various rivals to the throne, but they didn’t murder their own off-spring.

There’s a small amount on science towards the end of the exhibition. As the caption says,

“The books that Shah ‘Abbas gave the shrine of Iman Riza included an early text from the 1200s on medicinal plants by the ancient Greek scientist Dioscorides. Translated from Syriac into Arabic, his text was one of the foundation stones of medieval Islamic medicine.”Beside this was a page from book four of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica, with a picture of something I thought might be a radish, whose seeds it recommends,

“as a purgative, for bruises and itchy skin, and, when, chewed for toothache and painful gums.”Oddly the illustration doesn’t give the name of the plant – only the picture, which I can see leading to wrong prescriptions. The caption guesses stavesacre (Delphinium staphisagria), though Wikipedia warns that “all parts of this plant are highly toxic and should not be ingested in any quantity.”

Perhaps the most interesting item in the whole exhibition, though, is one small, innocuous image of the shah with a caption that doesn’t quite spell-out what it seems to be showing. We know it’s the shah from his tell-tale huge moustache (he apparently set a fashion). The image, painted by Muhammad Qasim in 1627 and on loan from the Louvre, has the shah sitting rather close to a long-sideburned page boy. The caption translates the Arabic text: it’s a romantic poem.

Perhaps the most interesting item in the whole exhibition, though, is one small, innocuous image of the shah with a caption that doesn’t quite spell-out what it seems to be showing. We know it’s the shah from his tell-tale huge moustache (he apparently set a fashion). The image, painted by Muhammad Qasim in 1627 and on loan from the Louvre, has the shah sitting rather close to a long-sideburned page boy. The caption translates the Arabic text: it’s a romantic poem.This, we’re told, is from a picture album for the shah’s own private enjoyment. It includes the impression of a royal seal, suggesting it’s not propaganda. The Hadrian exhibition had a whole section on pretty boy Antinous – though left him out its family guide. Whatever the purpose or origin of the image here, and though the exhibition frames the picture with a discussion of the succession, it's odd the reference to the Shah's sexuality is only implicit.

Labels:

history,

iran,

killings,

museum,

things as-yet unannounced

Thursday, May 28, 2009

What’s brown and sounds like a bell?

The splendid fellows at the BBC Archive have posted lots of films and photos of the Palace of Westminster’s clock tower, also known as Big Ben. A medal – and cake – to whoever came up with such a brilliant idea.

(As I've blogged before, the bell is 150 years-old this year, and Big Ben’s own website has a feast of good stuff, too.)

Speaking of things politic, have been catching up on a week’s blogs, much of them bothered by MP’s expenses. Impressed by Peter on expenses and then on transparency, and Web of Evil on expenses and earlier on ID cards.

(Hungary was fun and sunny; photos on Facebook and will blog more the far side of a few pressing deadlines…)

(As I've blogged before, the bell is 150 years-old this year, and Big Ben’s own website has a feast of good stuff, too.)

Speaking of things politic, have been catching up on a week’s blogs, much of them bothered by MP’s expenses. Impressed by Peter on expenses and then on transparency, and Web of Evil on expenses and earlier on ID cards.

(Hungary was fun and sunny; photos on Facebook and will blog more the far side of a few pressing deadlines…)

Monday, May 18, 2009

The band that never existed

To the Roundhouse last night for a gig by the Radiophonic Workshop, formerly of the BBC. The tone of the night was set by the A5 flyer:

I did glean a few top facts from the evening. The building in Maida Vale once used by the Radiophonic Workshop is now where Jonathan Ross records Film 2009; a little, hot room right at the end of a long, long corridor. And the Roundhouse itself was built for turning trains round. (There were boards up detailing its history, with Victorian railway magnates in tall top hats, and some groovy nudity when the place was home to Oh, Calcutta!)

After some gins and a plastic pint of Becks, we squeezed into the dark mosh pit to stand for a couple of hours listening to nostalgic strange noises. In the best traditions of rock and roll, the band appeared later than billed, just as the audience were getting restless. Then there they were: Mills, Limb, Kingsland, Howell and Ayres. And – hooray! – all wearing lab coats. (Rain Rabbit has photos from the gig on Flickr.)

The Radiophonic Workshop are, of course, responsible for the odder bits in the soundtrack of our lives. They created the Doctor Who theme tune and the noise of the TARDIS coming and going. But they also produced tunes and effects for schools’ programmes, documentaries and various dramas.

It was, to be honest, a mixed bag of music, covering the enormous range of the workshop’s output. Strange, alien stuff led into jaunty, light jazz. Tunes you could sing along to followed the sound of space. The barn-owl-tastic titles to 80s computer programming show Micro Live got a big cheer from the geeks.

Between the tunes there were good-natured if geeky intros from the band-members. Kingsland explained that the Radiophonic Workshop had closed in 1997, but – being British – were “blustering on anyway”.

A lot of their stuff was painstakingly hand-made in the days before the synth. These days, as Peter Howell admitted at one point in the evening, their entire output fits on one Mac. A lot of the workshop’s work was inventing pre-recorded sounds and editing them together – all done with tape and razor blades. The gig nicely mixed the recordings with live performance. There were live versions of the regeneration from Tom Baker into Peter Davison and the theme to John Craven’s Newsround (electric guitars and drums complimenting John Baker’s pre-recorded and played-with bottle tops). The enthusiasm of and for the old duffers was what made this such fun. An entirely bizarre line-up but a great night out.

It’s not just the tunes and noises the workshop produced themselves: they were hugely influential on the wilder ends of pop. Coincidentally, tape loops featured in Saturday’s St Etienne gig, as reported by Paul Cornell.

You’ve got three days left to listen again to Night Waves where Matthew Sweet chats to the Radiophonic Workshop prior to the gig. And, if that doesn't sate you, whizzo documentary The Alchemists of Sound is up on YouTube.

“To celebrate the 50th anniversary of this unique institution a few of the old inmates, now on day release, have put together a programme of music from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. There will be plenty of old favourites and some new material, played by the band that never actually existed… until tonight.”It then lists the players and their 18 synthesizers.

“Apple’s Logic Audio provides surround playback, with MainStage allowing us to use the latest virtual synths alongside the vintage hardware.”The audience was pretty much what you’d expect: scruffy, sweaty boys lashing through the lager. I saw plenty of chums there, though me and M. were too late for the Q&A. Expect we’d have known all the answers anyway.

I did glean a few top facts from the evening. The building in Maida Vale once used by the Radiophonic Workshop is now where Jonathan Ross records Film 2009; a little, hot room right at the end of a long, long corridor. And the Roundhouse itself was built for turning trains round. (There were boards up detailing its history, with Victorian railway magnates in tall top hats, and some groovy nudity when the place was home to Oh, Calcutta!)

After some gins and a plastic pint of Becks, we squeezed into the dark mosh pit to stand for a couple of hours listening to nostalgic strange noises. In the best traditions of rock and roll, the band appeared later than billed, just as the audience were getting restless. Then there they were: Mills, Limb, Kingsland, Howell and Ayres. And – hooray! – all wearing lab coats. (Rain Rabbit has photos from the gig on Flickr.)

The Radiophonic Workshop are, of course, responsible for the odder bits in the soundtrack of our lives. They created the Doctor Who theme tune and the noise of the TARDIS coming and going. But they also produced tunes and effects for schools’ programmes, documentaries and various dramas.

It was, to be honest, a mixed bag of music, covering the enormous range of the workshop’s output. Strange, alien stuff led into jaunty, light jazz. Tunes you could sing along to followed the sound of space. The barn-owl-tastic titles to 80s computer programming show Micro Live got a big cheer from the geeks.

Between the tunes there were good-natured if geeky intros from the band-members. Kingsland explained that the Radiophonic Workshop had closed in 1997, but – being British – were “blustering on anyway”.

A lot of their stuff was painstakingly hand-made in the days before the synth. These days, as Peter Howell admitted at one point in the evening, their entire output fits on one Mac. A lot of the workshop’s work was inventing pre-recorded sounds and editing them together – all done with tape and razor blades. The gig nicely mixed the recordings with live performance. There were live versions of the regeneration from Tom Baker into Peter Davison and the theme to John Craven’s Newsround (electric guitars and drums complimenting John Baker’s pre-recorded and played-with bottle tops). The enthusiasm of and for the old duffers was what made this such fun. An entirely bizarre line-up but a great night out.

It’s not just the tunes and noises the workshop produced themselves: they were hugely influential on the wilder ends of pop. Coincidentally, tape loops featured in Saturday’s St Etienne gig, as reported by Paul Cornell.

You’ve got three days left to listen again to Night Waves where Matthew Sweet chats to the Radiophonic Workshop prior to the gig. And, if that doesn't sate you, whizzo documentary The Alchemists of Sound is up on YouTube.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

“Have a go to see what happens”

Blood and Guts – A History of Surgery is a fascinating, gruesome, layman-friendly book, packed with anecdotes and horror stories. Author Richard Hollingham, following Michael Mosley's TV series, takes us from Galen's treatment of gladiators in the Second Century AD, through Vesalius and Paré in the Sixteenth Century to 2006, where Stuart Carter was freed from paralysis by Parkinson's disease through the use of electrical brain implants.

Hollingham argues there were four obstacles to successful surgery: surgeons needed to understand the workings of the body (usually through dissection of dead bodies); they had to learn from the experience methodically; they had to bypass the pain of an operation (by inventing anaesthetic); and they had to prevent infection.

So we follow the haltering steps towards achieving these goals, such as the discovery of chloroform and carbolic soap. We also see some of the cul-de-sacs we've since backed out of – usually the result of surgeons insisting they know best rather than looking at the evidence.

Hollingham is also hot on the statistics – no two patients are the same, so operations are judged not on a single win or lose, but the percentage of success when trying the same procedures time and again. Before the discovering of carbolic soap, infection was fought by operating quickly; Liston could remove a leg in 30 seconds.

The two world wars meant the raw material with which to make extraordinary advance in grafts and the treatment of burns. There are harrowing stories of the multitude of operations suffered by men without faces – and there are also harrowing photos. This is really not a book for the squeamish. But I'm less squeamish of blood and guts per se as unnecessary pain and procedures...

There's some terrifying stuff about lobotomies. The 1941 operation on Rosemary Kennedy (sister of future President John F.) left her,

And yet Hollingham doesn't talk about one of the biggest areas of surgery today – and one of the most morally problematic. Cosmetic surgery is booming, yet its only mention in the book is the cautionary tale of Gladys Deacon, a beautiful lady in 1903 who wanted a more beautiful nose. The hot paraffin wax surgeons injected her face turned her into a “freakish waxworks dummy” (p. 222).

Nor is there much on the philosophy of surgery – the Hippocratic oath, the impact of the National Health Service on surgeons (who insisted, when it began, that they kept their private work) and the role of the private sector today. Perhaps the NHS bits would be too parochial for a book that tries to cover the global history of surgery (and its covered anyway in NHS plc), but who pays for surgery – and for surgeon's mistakes – would have lifted this fascinating pop-history into something more profound.

(No, I've not yet read Bad Science.)

Hollingham argues there were four obstacles to successful surgery: surgeons needed to understand the workings of the body (usually through dissection of dead bodies); they had to learn from the experience methodically; they had to bypass the pain of an operation (by inventing anaesthetic); and they had to prevent infection.

So we follow the haltering steps towards achieving these goals, such as the discovery of chloroform and carbolic soap. We also see some of the cul-de-sacs we've since backed out of – usually the result of surgeons insisting they know best rather than looking at the evidence.

Hollingham is also hot on the statistics – no two patients are the same, so operations are judged not on a single win or lose, but the percentage of success when trying the same procedures time and again. Before the discovering of carbolic soap, infection was fought by operating quickly; Liston could remove a leg in 30 seconds.

“The morality rate from Robert Liston's operations was remarkably good. Between 1835 and 1840 he conducted sixty-six amputations. Ten of his patients died – a death rate of around one in six. About a mile away at St Bartholomew's Hoispitals, surgeons were sending one ion four patients tot he mortuary, or 'dead house', where the all too frequent post-mortems took place.”Yet Hollingham is also quick to show that the medical heroes are also all-too human.Richard Hollingham, Blood and Guts, p. 38.

“Jealous rivals would whisper that Liston was so quick that he once accidentally amputated the penis of an amputee ... The most worrying incident for his students occurred during an amputation when Liston accidentally amputated an assistant's fingers. The outcome of this operation was horrific: the patient died of infection, as did the assistant, and an observer died of shock. It was the only operation in surgical history with a 300 per cent mortality rate.”All to often the effort is, “Well, we don't know, but we'll try this...”, and slowly, over the centuries, that philosophy has benefited us all.Ibid., pp. 41-2.

The two world wars meant the raw material with which to make extraordinary advance in grafts and the treatment of burns. There are harrowing stories of the multitude of operations suffered by men without faces – and there are also harrowing photos. This is really not a book for the squeamish. But I'm less squeamish of blood and guts per se as unnecessary pain and procedures...

There's some terrifying stuff about lobotomies. The 1941 operation on Rosemary Kennedy (sister of future President John F.) left her,

“a very different person. Slow and emotionless, she was hardly able to move or speak. Although she eventually learnt to walk again, she was left permanently disabled and ended up in a residential institution in Wisconsin ... Freeman never said a word about the case. It was in his best interests not to publish the details of any high-profile failures.”Walter Freeman refined and developed the lobotomy, after it had first been performed in 1935 by Portuguese surgeon Egas Moniz. By 1946 Freeman was now offering a new refinement, the “transorbital” lobotomy. The “transorbital” bit is where they shoved an ice-pick up through your eye socket to detach bits of your brain. It was a shockingly quick procedure, and doctors were quick to recommend it, too.Ibid., pp. 279-80.

“Freeman ... personally performed about three and a half thousand lobotomies, and trained doctors across the world. In total, it is thought that around one hundred thousand people were lobotomized.”The case of Howard Dully, an eleven-year-old boy who wasn't getting on with his step-mum, is like something out of a fairy tale. Her evidence for why the wayward child should receive the treatment included that “he daydreamed and scowled if the TV was tuned to some programme other than the one he liked,” (p. 285). Using “orbitoclasts” - a step up from ice picks – Freeman operated on the boy on 16 December 1960.Ibid., p. 283.

“Howard has spent most of his life coming to terms with what happened to him. He suffered problems with work, relationships and money. He drifted in and out of jobs and in and out of jail. Gradually, he was able to piece his life back together. Today he holds down a job as a bus driver. There is absolutely nothing about him to suggest that he has two black holes in his brain. What saved him from going completely off the rails was probably his youth. Howard's young brain was able to rebuild neural pathways and compensate for the damage Freeman inflicted.”Yet Freeman is not portrayed as monster, for all he “operated on a total on nineteen children, including a four-year-old,” and he ignored criticism and the new drugs that “did much the same thing only without the danger or permanence of surgery,” (p. 287). Hollingham lays as much blame on the authorities who let Freeman continue working “when the procedure was discredited and opposed by almost the entire medical establishment,” (p. 288).p. 287.

“But it is difficult to reconcile the image of a monster with the kind and gentle doctor his patients encountered. When the lobotomy was conceived it seemed to provide the only treatment for chronic mental illness. It certainly transformed some people's lives for the better.”In fact, Freeman spent the last five years of his live travelling “some fifty thousand miles” tracking down former patients to see how they had fared.p. 288.

“To the end of his life he believed in what he had done, and he believed he was right.”Hollingham says “Freeman's greatest failure of judgement was not knowing when to stop,” (p. 288), but that sits uncomfortably with what follows. In the 1950s, the US intelligence agency were “toying” with “brainwashing individuals, invariably communists”. In 1967, psychiatrist Frank Ervin and neurosurgeon Vernon Mark's proposal in “the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association” to prevent urban riots by subduing black rioters with brain implants (one of Ervin's medical students, Michael Chricton, later wrote The Terminal Man). In 1972, psychiatrist Robert Heath proposed using “brain implants to 'cure' homosexuality,” (all p. 293).p. 289.

And yet Hollingham doesn't talk about one of the biggest areas of surgery today – and one of the most morally problematic. Cosmetic surgery is booming, yet its only mention in the book is the cautionary tale of Gladys Deacon, a beautiful lady in 1903 who wanted a more beautiful nose. The hot paraffin wax surgeons injected her face turned her into a “freakish waxworks dummy” (p. 222).

Nor is there much on the philosophy of surgery – the Hippocratic oath, the impact of the National Health Service on surgeons (who insisted, when it began, that they kept their private work) and the role of the private sector today. Perhaps the NHS bits would be too parochial for a book that tries to cover the global history of surgery (and its covered anyway in NHS plc), but who pays for surgery – and for surgeon's mistakes – would have lifted this fascinating pop-history into something more profound.

(No, I've not yet read Bad Science.)

Saturday, May 16, 2009

Partial eclipse

I'm off to Hungary next week for a brother's wedding. Spent a weekend in Budapest for my stag do five years ago, have drunk some good Tokay and I've also seen Countess Dracula, but otherwise don't know a great deal about the country.

So my soon-to-be sister-in-law leant me Egri csillagok – or, in English, Eclipse of the Crescent Moon, A tale of the siege of Eger, 1552 – by Géza Gárdonyi. First serialised in the Pesti Hirlap newspaper from Christmas 1899, the edition I read was translated into English by George F Cushing in 1991.

Wikipedia summarises the five sections of the book, which begins with two children, Gergely and Éva, being kidnapped by some villainous Turks. Gergely is clever and he and Éva escape. Years later, when Buda has been taken by the Turks, they meet up again and get married, have some adventures before getting caught up in Eger as it's besieged by an army of 200,000.

It's a rich and patriotic story, full of incident and fun characters. The Hungarian heroes are a lesson in most noble bravery; they're resourceful, canny and honest. Báliant Török, for example, finds dealing with the dishonest Turks hard work: “I'm not used to hiding my thoughts from other people,” (p. 182). Szalkay, meanwhile, knows who to shake hands with: “His practised eye told him [Miklós Réz] was not a gentleman,” (p. 425). During the siege itself there's a merry discussion of cutlery and recipes (pp. 426-7), and plenty of good-natured jokes.

When one naughty fellow, Hegedüs, is caught trying to negotiate with the enemy, he gets an unquestionably fair trial: Zoltay is even relieved of his duties as a judge for flaring up in anger. As Hegedüs swings from a gibbet we're left under no doubt that this is a sterling, civilised bunch.

There aren't a lot of shades of grey. The Turks are variously greedy, cruel, cowardly, sneaky, dishonest and hypocritical (yet apparently still better to live under than the Austrians). In general, it reminded me a lot of The Horse and his Boy. If I'd understood Edward Said's impenetrable prose (I think he's sort of saying the same things as Tusk Tusk), I might dare to call it Orientalist.

It's not as if the Turks can do anything right: they're mocked if they break their vow of abstinence of alcohol, and mocked if they stick with it. The new bey is described as,

When our heroes dare visit the Turk's own lands, there's a lot of wide-eyed pointing and gawping. As with the boozing, the Turk's odd behaviour gives clues to Hungarian norms:

Yet the book also pokes fun at the ignorance of its heroes. There's a glimpse of a map depicting,

Or there's the moment our heroes are shocked to hear from one spy of the bey's habit of drinking ink:

Further muddying the water, the Hungarian and Turkish languages are also very similar, as Jancsi explains:

(T Majlath compares Hungarian and Japanese words, but is also keen to state that these are only “similarities” ... “Nowhere do I claim that Magyar (Hungarian) is related to Basque, Etruscan, Japanese, Sanskrit, Sumerian, or Martian or whatever. I wouldn't dare to make such claims which are, after all, the sole prerogatives of Indo-European.”)

There are plenty of fun observations throughout. Zoltay is described as “a jolly man without a beard, so he was unmarried,” (p. 301). Later there's an example of a Christian not quite living the spirit of his order.

George Cushing's introduction talks about Gárdonyi's research and what bits of the story he's invented, and I'm looking forward to seeing the real castle for myself next week. But I'm also impressed by how Gárdonyi scoffs his cake and keeps it for the historical record. Because while we get a happy ending for Gergely and Eva, satisfying the romantic feel of the thing, the real history sits heavy on them; they've only won a reprieve.

But way, way back it's let us know Gergely's not so brilliant future. One reason for Gergely visiting Constantinople in Part III is so the author can let us in on what's to befall him.

So my soon-to-be sister-in-law leant me Egri csillagok – or, in English, Eclipse of the Crescent Moon, A tale of the siege of Eger, 1552 – by Géza Gárdonyi. First serialised in the Pesti Hirlap newspaper from Christmas 1899, the edition I read was translated into English by George F Cushing in 1991.

Wikipedia summarises the five sections of the book, which begins with two children, Gergely and Éva, being kidnapped by some villainous Turks. Gergely is clever and he and Éva escape. Years later, when Buda has been taken by the Turks, they meet up again and get married, have some adventures before getting caught up in Eger as it's besieged by an army of 200,000.

It's a rich and patriotic story, full of incident and fun characters. The Hungarian heroes are a lesson in most noble bravery; they're resourceful, canny and honest. Báliant Török, for example, finds dealing with the dishonest Turks hard work: “I'm not used to hiding my thoughts from other people,” (p. 182). Szalkay, meanwhile, knows who to shake hands with: “His practised eye told him [Miklós Réz] was not a gentleman,” (p. 425). During the siege itself there's a merry discussion of cutlery and recipes (pp. 426-7), and plenty of good-natured jokes.

When one naughty fellow, Hegedüs, is caught trying to negotiate with the enemy, he gets an unquestionably fair trial: Zoltay is even relieved of his duties as a judge for flaring up in anger. As Hegedüs swings from a gibbet we're left under no doubt that this is a sterling, civilised bunch.

There aren't a lot of shades of grey. The Turks are variously greedy, cruel, cowardly, sneaky, dishonest and hypocritical (yet apparently still better to live under than the Austrians). In general, it reminded me a lot of The Horse and his Boy. If I'd understood Edward Said's impenetrable prose (I think he's sort of saying the same things as Tusk Tusk), I might dare to call it Orientalist.

It's not as if the Turks can do anything right: they're mocked if they break their vow of abstinence of alcohol, and mocked if they stick with it. The new bey is described as,

“a coward and a fool ... Can someone brought up on water be anything else?”(It's a little like the Russians of the 1950s, as described in Edward Wilson's novel, The Envoy. The Russians won't trust those who aren't boozers, so spies learn to line their stomachs by drinking olive oil.)Géza Gárdonyi, Eclipse of the Crescent Moon, p. 271.

When our heroes dare visit the Turk's own lands, there's a lot of wide-eyed pointing and gawping. As with the boozing, the Turk's odd behaviour gives clues to Hungarian norms:

“Constantinople is a paradise for dogs. There are no courtyards here, or if there is anything like that, it is on the roof of the house, so there is no room anywhere for dogs. Those red-haired, fox-like creatures swarm in hundreds through the streets in some parts. The Turks do not disturb them; indeed, when one or other of them has a litter of puppies, they throw down rags or a bit of rush-matting by the gate to help them. Those dogs keep Constantinople clean and tidy. Each morning the Turks empty the square tin dustbins beside their gate. The dogs eat the contents. They devour everything except iron and glass. And the dogs are not ugly or wild either. You can pat any of them, and they will wag their tail with delight. There is not one of them that is not glad to be stroked.”So in Hungary the dogs are wild and ugly, and shooed out of sight. No wonder its such a surprise to find them being friendly. I assume as well as eating the rubbish, the dogs helped keep down the plague.Ibid., p. 254.

Yet the book also pokes fun at the ignorance of its heroes. There's a glimpse of a map depicting,

“the three continents. (At that time scholars had not yet mapped out the land of Columbus; there was merely a rumour that the Portuguese had discovered a hitherto unknown continent. But nobody knew how much truth there was in it. And even Columbus had not yet even dreamt of Australia.)”That's in Part II, set in 1541 – 50 years after Columbus stumbled into America. I wonder how long it took for word to get round?Ibid., p.110.

Or there's the moment our heroes are shocked to hear from one spy of the bey's habit of drinking ink:

“'What?'For all the book protests, the Hungarians and Turks don't half overlap. The stealing of children – as seen in Part I – is a reasonably common occurrence, and there are numerous instances of people who've swapped sides and / or forgotten their heritage. Though the author prefers not to point it out, there are examples of noble Turks and of lazy, good-for-nothing Hungarians.

'Ink. He drinks ink like we do wine, sir. Morning, noon and night he drinks nothing but ink.'

'Come off it! It can't be ink.'

'Oh, but it is ink, sir, good genuine black ink. They make it out of some kind of bean, and it's so bitter that I was still spitting it out the day after when I tasted it. And in Turkish the name of the bean is kahve.'”Ibid., 349.

Further muddying the water, the Hungarian and Turkish languages are also very similar, as Jancsi explains:

“'Well, for example: elma = alma [apple], benim = enyim [mine], baba = papa, papuch = papucs [slippers], daduk = duda [bagpipes] chagana...'This suggests the cultures have been mixing for centuries. I gather Hungarian is a Uralic language and shares roots with Finnish and Estonian, while a chum in the pub says its also been linked as far as Japanese.

'Csákány [axe]!' cried Eva, clapping.”Ibid., pp. 227-8.

(T Majlath compares Hungarian and Japanese words, but is also keen to state that these are only “similarities” ... “Nowhere do I claim that Magyar (Hungarian) is related to Basque, Etruscan, Japanese, Sanskrit, Sumerian, or Martian or whatever. I wouldn't dare to make such claims which are, after all, the sole prerogatives of Indo-European.”)

There are plenty of fun observations throughout. Zoltay is described as “a jolly man without a beard, so he was unmarried,” (p. 301). Later there's an example of a Christian not quite living the spirit of his order.

“The office of bishop isn't only an ecclesiastical post, but a military one, too. Every bishop has his own troops. And every bishop is also a captain.”When we get to the siege itself, there's plenty to be said on tactics, experience and intelligence in war. There's stuff about when best to fire on the enemy and how to check if they're trying to mine under the castle.Ibid., p. 360.

“Get the drummers to put their drums on the ground too and spread peas on them ... Go round all the sentries and tell them to examine the drums and dishes [of water] each time they pass them. As soon as there's any movement of water in the dishes or peas and shot on the drums, they're to report immediately.”You also feel the historical moment, as new technologies threaten the old ways of warfare. On page 325, Cecey declares that, “A good bow is worth more than any rifle.” Yet 50 pages later we're told that gunfire is in the Hungarians' blood:Ibid., p. 450.

“Ever since the discovery of gunpowder, Eger more than any other place in the world had resounded to the noise of firing. Even today spring festivals, firemen's parties, elections, choir celebrations, garden parties and public performances are inconceivable without being preceded by gunfire. The gun is a substitute for the poster. Sometimes there are posters too, but all the same they do not dispense with the gun. In the fortress there are always a few mortars lying around in the grass. Anyone who likes fires them. So how could the folk of Eger feel afraid?”As the siege continues, these folk of Eger have to roll their sleeves up. It's a great bit of patriotic fervour – like the ordinary citizens who help Spider-Man or Batman. It's also thrillingly blood-thirsty:Ibid., p. 367.

“Mrs Gáspár Koscis, a sturdy figure, drenches an approaching aga with a long bear so thoroughly with boiling water that when he makes a grab at his beard it comes away in his hand. Another woman seizes a flaming log from the nearby fire and strikes a Turk in the face with it so that sparks fly fly from it in all directions. The other women repulse the pagans with weapons.The all-important differences between the Hungarians and Turks also play their part:

'Jesus, help us!'

'Strike them! Strike them!' roars the smith from Felnémet.

He rushes with his hammer in among the women. Three Turks are fighting there back to back. He strikes one so hard on the head that his brains spatter out his nose and ears.”Ibid., pp. 536-7.

“Actually it was the soup that beat off the attack. The Turks had got used to fire, sword and pike, but knew hot soup only in spoons. As the boiling paprika-spiced liquid poured down the first ladder, the men seemed to be swept off it. The swarm of men at the foot of the ladders also jumped away. Some clutched at their hands, others their faces, others their necks. Covering their heads with their shields they backed away from the walls cursing.”As the odds continue to stack up against our plucky heroes, it gets ever more gripping. Who lives? Who dies? Who will the siege?Ibid p. 478.

George Cushing's introduction talks about Gárdonyi's research and what bits of the story he's invented, and I'm looking forward to seeing the real castle for myself next week. But I'm also impressed by how Gárdonyi scoffs his cake and keeps it for the historical record. Because while we get a happy ending for Gergely and Eva, satisfying the romantic feel of the thing, the real history sits heavy on them; they've only won a reprieve.

But way, way back it's let us know Gergely's not so brilliant future. One reason for Gergely visiting Constantinople in Part III is so the author can let us in on what's to befall him.

“When you've grown into a fine bearded man and a gentleman, that's where the wicked Turks will entice you into a trap and clap your hands and feet in irons! And only death will release you from them...”And again later:Ibid., pp. 228-9.