Last week I hosted an event for the Writers' Guild of Great Britain with the last two winners of our Best First Novel Award - Aamina Ahmad for The Return of Faraz Ali (Sceptre, 2022) and Eli Lee for A Strange and Brilliant Light (Quercus, 2021). You can see the full thing here:

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

Monday, February 13, 2023

The Morbid Age, by Richard Overy

"Ideas do not operate in a social vacuum. Much of what follows explores the many ways in which ideas were communicated and how extensively, socially and geographically. The discourse did not remain the preserve of an isolated cultural elite but flourished in the first real age of mass communication." (p. 5)

He lists the uptake of radio licenses, the sales of cheap paperbacks, the wide variety of lectures and summer schools, even the instructional films on frank subjects (ie sex).

"British society had a thirst for knowledge and a mania for voluntary associations willing to supply it. The state played a part in this process by developing more sophisticated statistical measurement and applying this to areas of policy or by identifying areas of key public concern which the government could review. The government enquiries on the trade in arms, on sterilisation policy, mental defect, population development and the depressed areas supplied ammunition for the public debates on social degeneration, economic crisis and war." (p. 375)

Historical incidents are used to show how people took or shifted positions. There's nothing on the "Spanish" flu and little on the Wall Street Crash, presumably because they didn't challenge people's previously held views. But there's lots on how the Spanish Civil War challenged the large and well-organised pacifist cause. For example, Overy quotes Julian Bell, nephew of Virginia Woolf, in a letter from 1937 to EM Forster as Bell made his way to fight - and die - in Spain:

"At this moment, to be anti-war means to submit to fascism [and] to be anti-fascist means to be prepared for war." (p. 339, in a section quoting from PN Furbank's EM Forster: A Life (London, 1977), pp. 223-4, and Mepham's Virginia Woolf, pp. 168-9.)

Overy details the impact that this and Bell's death had on this literary circle, many of whom initially held to their prior anti-war convictions. This then dovetails with the Prime Minister's efforts to avoid conflict with Hitler, and the gradual shift in public attitudes in the lead up to the Second World War.

"The most remarkable convert was the pacifist philosopher Cyril Joad, whose absolute renunciation of war was reiterated publicly right up to its outbreak and beyond. After wrestling with his convictions for some months in 1940 he experienced a dramatic change of heart. Writing in the Evening Standard in August 1940 under the headline 'I Was a Life-long Pacifist, but Hitler Changed my Mind', Joad explained that the things he valued about England - 'the free mind and the compassionate heart, the love of truth ... of respect for human personality' - were absolutely endangered by a Hitler victory which would usher in a Dark Age." (p. 352)

[Note to self: this is, broadly, the same kind of shift embodied in Alydon the Thal in the first Doctor Who story to feature the Daleks.]

What really struck me is the fatalism in all this: the widespread sense that while it might have been necessary to go to war with Hitler, such conflict would more likely end than save civilisation. That sentiment, I think, haunts The Lord of the Rings (I've been listened to the BBC radio version recently, more of which anon). It adds something to what I've been told about my grandparents' hastily arranged weddings (in September 1939 and 1940 respectively). It permeates into the book I'm writing now on David Whitaker, and his fatalistic view that history cannot be changed and we are simply swept along in its course. Yes, an idea to shift the ground beneath me.

Overy opens the book with the recollection of a telling conversation with the historian Eric Hobsbawm in which,

"he told me that he could remember a day in Cambridge in early 1939 when he and some friends discussed their sudden realization that very soon they might all of them be dead. This did strike me as surprising, and it runs against the drift of the [Hobsbawm] memoirs, in which he argued that communists were less infected by pessimism than everyone else because of their own confidence in the future." (p. xiii)

Even the faithful shared - if just on one day - that sense of foreboding. But then they were swept on.

Friday, January 27, 2023

Body Parts - Essays on Life-Writing, by Hermione Lee

How brilliant, for example, to note Angela Thirkell's "blithe lack of sexual awareness" by quoting from a scene in The Brandons (1939) in which characters at a village fete take a ride on a merry-go-round made of wooden animals:

"'I knew it was you on the ostrich,' she [Lydia] said to Delia ... 'I say, someone's on my cock.'

'It's only my cousin Hilary,' said Delia. 'He won't mind changing, will you, Hilary...'

Mr Grant, really quite glad of an excuse to dismount, offered his cock to Lydia, who immediately flung a leg over it, explaining that she had put on a frock with pleats on purpose, as she always felt sick if she rode sideways...

... 'I know that once Lydia is on her cock nothing will get her off. I came here last year ... and she had thirteen rides." (Lee, p. 180, quoting Thirkell pp. 260-2)

This is all the more extraordinary when Lee then tells us that Thirkell was the mother of Colin Macinnes, author of Absolute Beginners (1959) and other bold works exploring sexuality and decadence. As a result, the quoted passage becomes something else, indicative of the clash between mother and son.

Lee quotes juicy bits from a number of other biographies, and like her I'm drawn to what she calls the "brutal, funny and helpful" advice given by the writer Colette to actress Marguerite Moreno:

"You lose most of your expressiveness when you write... Stick in a description of the decor, the guests, even the food... And try, oh my darling, to conceal from us that it bores the shit out of you to write." (Lee, p. 117, quoting Judith Thurman's Secrets of the Flesh - A life of Collete (1999), p. 543)

Or there's the way she explains the shock that met Ellen Glasgow in the 1930s writing stories about degeneration, extramarital love and scientific arguments against religion etc, then quotes one of Glasgow's characters - "failed philosopher, John Fincastle" - to get a sense of the impact on the author's own career.

"Nobody could earn a livelihood in America by thinking the wrong thoughts." (Lee, p. 124, quoting Glasgow's Vein of Iron (1935), p. 38)

Body Parts is peppered with this stuff. Even the briefest reference to Jane Porter's 1803 novel Thaddeus of Warsaw (p. 125) ignited my interest, prompting additional reading and connections - and perhaps a new project to lose myself in...

But what about things I'm writing now? Two essays in this collection, "Virginia Woolf's nose" at the start and "How to End It All" at the conclusion, address the ways that accounts of a person's death are often written to cast light or reflection on the life as a whole. Imagining the subject looking back over their lives is a a conceit, imposing neatness on what can be untidy ends. In fact it's not just death: lives are often untidy and inconsistent, and Lee is good on exploring that - how to address contradictory or outlier evidence, or the way a theory about someone's life can be repeated by biographers until it takes on the authority of "fact". Lee says,

"this process of cumulative reiteration happens all the time" (p. 135)

I'm mindful of that as I write my biography of David Whitaker - and also my book on his 1964 Doctor Who story, The Edge of Destruction, where I can see such reiteration in the "facts" about early Doctor Who. I'm not sure Lee provides answers to the knotty questions that she raises about how we go about telling a story without fictionalising real life - but I think that's the point. There is plenty to think about; she directs us towards the things to worry at.

Saturday, December 03, 2022

Charles Hawtrey 1914-1988 The Man Who Was Private Widdle, by Roger Lewis

“pampered with port-soaked sugar lumps, its bread and butter sprinkled with Cyprus sherry, [and] used to walk into doors and see double when chasing mice.” (pp. 70-71)

This is just one extraordinary, sad and savage anecdote in Roger Lewis's pithy biography. Lewis has been diligent in going through BBC and BFI paperwork and in talking to those who knew Hawtrey in person. As well as the cast and crew of various productions, Lewis spoke to cab drivers, publicans, neighbours, and is good on the gulf between the cheery, cheeky persona captured on film and the angry, lecherous drunk of real life.

Hawtrey's meanness is quite something:

“Of necessity [Lewis claims] he was frugal, penny-pinching. He maintained his account at the Royal Bank of Scotland (Piccadilly branch), because he believed the Scots would keep a beadier eye on their customers’ shillings. He’d lug bags of carrots from Leeds to Kent, because vegetables were cheaper in Yorkshire. He pilfered toilet rolls from public lavatories — or at least his mother did. She was notorious for wiping out supplies at Pinewood and, when rumbled, tried to flush away the incriminating evidence, which blocked the drains, closing down production on Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Hawtrey was told that in future his mother would have to be locked in his dressing room.” (p. 72)

That's a fantastic a story but I'm not sure it can be true as Chitty Chitty Bang Bang began filming in June 1967 and Wikipedia claims that Hawtrey's mum Alice died in 1965. Lewis doesn't provide a source.

There's lots on money here. Hawtrey and his costars did not get rich from the Carry On films but producer Peter Rogers did. Instead, Hawtrey converted his house in Kew into bedsits — though implied to Roy Castle while making Carry on Up the Khyber in 1968 that he owned a “block of flats”. But Lewis says this enterprise didn't work out, and Hawtrey ended up being “ripped off” (p. 89). He retired to Deal, got banned from all its pubs and finally collapsed in a hotel doorway.

It's a troubled end to a troubled career. Hawtrey “never mixed with the rich and famous” (p. 12), and yet and some notable early roles. As well as playing several women on stage, he understudied Robert Helpmann as Gremio in Tyrone Guthrie’s production of The Merchant of Venice at the Old Vic, the cast including Roger Livsey as Petruchio and, in a small part, the future novelist Robertson Davies. A couple of years later, Hawtrey was in the cast of New Faces, the show that debuted Eric Maschwitz's hit song, “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.”

But Lewis shares excerpts over three pages from polite, curt rejections from the 1940s and 50s. Then, on page 61, he gives a long list of names at the BBC that Hawtrey wrote to in radio and TV, but concludes that these were,

“all radio or television apparatchiks, and not a single one of these names rings any bells with me” (p. 61n).

In fact, the list includes television pioneer Rudolph Cartier, Cecil McGivern (Controller, then Deputy Director of Television) and Shaun Sutton (later Head of Drama). I recognised various jobbing staff directors from the drama department, and Graeme Muir from light entertainment. So Hawtrey wasn't just writing to “everybody at Broadcasting House, from the Director-General to the janitors”; this is evidence of his range and aspirations — a serious, dramatic actor as well as comic foil.

Friday, December 02, 2022

Clips from a Life, by Denis Norden

Before that, Whitaker was script editor for Light Entertainment at the BBC, at the same time that Denis Norden and Frank Muir were employed as advisers on comedy. Whitaker then succeeded Norden (and Hazel Adair) as chair of the guild. So I scoured this memoir for any telling detail.

As Norden admits, it's is a rather loose collection of memories, jotted down as they occurred to him and then assembled in rough chronological order. There's a lot on his love of puns and odd turns of phrase, and much of the history is given by anecdote. He doesn't mention Whitaker but provides some fun tales about people in the same orbit - Ted Ray, Eric Maschwitz, Ronnie Waldman, the sitcom Brothers in Law starring Richard Briers and June Barry (Whitaker's first wife), and the early days of the guild.

For example, there's the striking fact that Hazel Adair, co-creator of Compact and Crossroads, who was Norden's co-chair, “at the Guild’s first Awards Dinner opened the dancing with Lew Grade” (p. 281).

Norden's eye for comic detail means there's plenty of vivid, wry observations. I particularly liked this, on the cultures of cinema:

“During the early forties I did some RAF training in Blackpool, where I discovered the cinemas were in the habit of interrupting the main feature sharp at 4 pm every day, regardless of what point in the storyline had been reached, in order to serve afternoon tea. The houselights would go up and trays bearing cups of tea would be passed along the rows. After fifteen minutes, the lights would dim down again, the trays would be passed back and the film wold resume. Anyone unwise enough to be sitting at the end of a row at that point could be left holding stacks of trays and empty cups.” (p. 33)

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Countdown to the Moon #771

The things I held up at the beginning are:

The Moon - A celebration of our celestial neighbour (ed. Melanie Vandenbrouck, 2019), which accompanied the National Maritime Museum's exhibition The Moon

Doctor Who: Wicked Sisters (2020), in which Dr Who meets early lunar colonists all making the "great leap" in giving up their Earth citizenship. Oh, and some Sontarans.

Sunday, September 18, 2022

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, by Anne Brontë

Alex Jennings reads this version, though one long section - when Helen tells her own story - is read by Jenny Agutter. That underlines that this is a woman's story largely told by a man, but written by a woman. There's a lot on gender roles here, and the constrictions imposed by sex, class and power.

What's more, the conceit that this is an account of events that really happened isn't unusual for the time, but in this case it all feels more credible than the better-known and more goth-fantastic works of Bronte's sisters, ie Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. I'd need to read those again to judge whether it's more disturbing when such wicked men and part of everyday, ordinary life.

This novel builds on Anne's Agnes Grey, in which there was also a lot on the awful trap of making a bad marriage. Here, Helen is motivated to escape not by the threat to herself but to the lasting impact of her husband's behaviour on her son. He wants the boy to follow his example, and had him drinking wine and joining in the parties. In that way, it's about not bad individuals but a culture. How strange to be immersed in this as revelations came out about our now former Prime Minister partying through a crisis, "entitled" to do so by culture in which he grew up.

Thursday, September 15, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #582

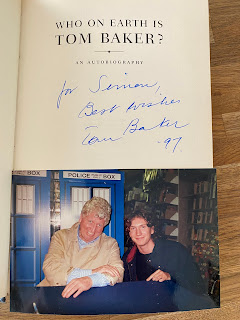

On page 11 of the mag, m'colleague Paul Kirkley recalls queuing for Tom Baker's autograph at the Friar Street Bookshop in Reading back in 1997. I was there, too - and here is a photograph of me with both Tom and hair.

|

| Tom and me, 1997 |

At the time, I'd just started my MA in science-fiction and had lofty hopes of writing things relating to Doctor Who. I'm now producing two Doctor Who audio plays starring Tom. Blimey.

Tuesday, August 23, 2022

Doctor Who Magazine #581

There are a couple of things in this issue by me, too. First, me and Rhys Williams detail the studio sets used for Episodes 1 and 2 of The Abominable Snowmen, recorded on 15 and 16 September 1967 - the latter the day on which my mum and dad got married. Rhys and Iz Skinner have then recreated this set-up in CGI. Truly, the set designers made those old TV studios bigger on the inside.

Then, to accompany the series of articles by Lucas Testro on writer Donald Cotton, including his original, hand-written drafts for 1965 story The Myth Makers, my latest "Insufficient Data" infographic is the Trojan horse as designed by the First Doctor. Ben Morris' illustration, of an outline scratched into an ostracon, is a delight - and more real history than myth.

Saturday, July 23, 2022

Penelope Fitzgerald - A Life, by Hermione Lee

"Dillwyn had his fiftieth birthday party at the Spread Eagle Inn at Thame, a chaotic event at which the notoriously grandiose and eccentric landlord locked up all the lavatories, so that the guests had to pee in the gardens, pursued by ferocious bees, and the only food provided was a dish of boiled potatoes. (This story may have grown in Penelope's telling of it over the years.)" (p. 40)

This Dillwyn, Fitzgerald's uncle, is the Dilys Knox whose work on codebreaking at Bletchley during the war I also ready knew about. His brother Ronald is the Ronald Knox whose writings on Sherlock Holmes I've noted in the Lancet. Their brother Evoe Know, editor of Punch, was also a name I'd seen before, but I'd never made the connection between these Knox brothers, or that Fitzgerald was Evoe's daughter. The book is full of such connections - Fitzgerald's children friends with the young Ralph and Joseph Fiennes, Fitzgerald's family close to that of EH Shepard, illustrator of Winnie the Pooh.

By chance, I went to see Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 AD at the cinema about the same time as reading the section about Grace, the canal boat on which Fitzgerald lived in the early 1960s, and on which she based her novel Offshore. Lee tells us (p. 144) that Grace was moored opposite St Mary's Church, Battersea - which is where Peter Cushing is standing when he sees a Dalek emerge from the Thames. So the background of those shots is what inspired a Booker prize-winning novel. I initially hoped that perhaps Grace was one of the bleak-looking boats visible in the film, but Fitzgerald's modest home sadly sank in 1963, taking with it many of her prize possessions just when she had so little left to lose.

(There's another Doctor Who connection: in about 1969, Fitzgerald owned an "old 1950s car" called Bessie (p. 219), just as Jon Pertwee's Third Doctor was first motoring about in his vintage-looking kit car of the same name.)

Lee tells us when she doesn't know something, or at least can't be sure. And she's brilliant at using Fitzgerald's fiction to tease out details of the author's real life - not that anything in a novel must be based on real experience, but that the narrative is revealing of a state of mind. At one point, Lee cites the owner of the shop on which The Bookshop was based, writing to Fitzgerald in praise of the novel but underlining differences between fact and fiction (real life was, apparently, more benign). Elsewhere, we close in on a man who may be the older, married colleague we know broke Fitzgerald's heart. Lee names her suspect, and presents a good case for him being the one, then admits there's not really enough here but tantalising fragments.

There is still plenty that's unknowable - and, as Lee admits at the end, plenty that Fitzgerald kept to herself to the end. But there's a vivid portrait here, a sense of Fitzgerald as a real, complex and contradictory person. I feel I know Penelope Fitzgerald now: the person, the work, the extraordinary, often difficult life. This is more than portraiture: it is vivid history; it is animation.

I'm keen to read Fitzgerald's own work of biography, The Knox Brothers, about her father and his brothers. And I'm keen to read Human Voices, a novel based on her own experience working at the BBC during the war. And Hermione Lee's Body Parts: Essays on Life Writing looks very good, too.

Sunday, July 10, 2022

Once Upon a Galaxy: The Making of the Empire Strikes Back, by Alan Arnold

His detachment is quickly evident. The diary starts on 3 March 1979 with the crew struggling through a blizzard to reach Finze in Norway for the start of location shooting. Arnold mutters that in these treacherous conditions no one helped him unload the suitcases from the train, singling out Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker in the film) in particular.

"But [I] told myself without total conviction that Mark was probably more concerned about his [pregnant] wife." (p. 5)

Yes, that may have been on his mind.

Arnold details the problems faced by the production and the ingenious solutions: shooting key scenes in the snow just outside their hotel; getting Harrison Ford (Han Solo) to join them last-minute as the schedule is changed; the logistical response to mounting costs and delays.

There's plenty of great detail, not least because Arnold had access to the lead actors and a wide range of those on the crew. There's a good interview with the notoriously reticent Harrison Ford on page 24, though the actor later brushes off a second attempt. I didn't know that the film's Snowspeeders were designed by Ogle Design Ltd, "a company better known for its Reliant sports car (p. 39), and I like production designer Norman Reynolds' description of these new creations as flying "close to the surface like an airborne tank." (p. 43).

It's interesting to see how practicalities shaped things, and how very different Star Wars might have been: the carbon-freezing of Han Solo, described at times here as his "execution", covered the fact that Ford might not have featured in the third film. On 15 May 1979, well into production, producers George Lucas and Gary Kurtz take Sir Alec Guinness out to lunch to discuss whether he will participate in the film (p. 85), something still apparently in doubt until 5 September when he turns up for his single day (p. 240). At one point Lucas suggests the part might have been recast.

Arnold is a little pretentious at times, sharing a history of the medieval Mummers (p. 60), or likening new character Boba Fett to Shakespeare's Richard II (p. 67). But he's also got a good eye for the telling, incongruous moments.

"Of England it's alleged that everything there stops for tea, but this is not true in the film business. It is taken on the run, without interruption to the work continuing on the floor. Morning and afternoon, trolleys bearing urns of tea and coffee are wheeled onto the soundstages by ladies whom you suspect have spent the interim studying their horoscopes. They are actually immune to surprise, even when the lineup for tea includes, as it did today on the ice-cavern set [4 April], a platoon of snowtroopers in white armoured suits, a robot, Darth Vader, and the Wampa Ice Creature. The imperturbable tea ladies served them all with their characteristic cool, as calm as Everest explorers confronted by an abominable snowman. They know that anyone who enjoys a cup of tea can't be all that abominable." (p. 61)

There's an especially extraordinary sequence, pp. 128-147, in which Arnold has director Irvin Kershner miked up while shooting the pivotal scene of Han Solo's "execution" in the carbon-freezing chamber. He and Ford puzzle over dialogue and motivation, honing the words on the page into something really powerful. But Carrie Fisher (Princess Leia) then objects to getting these changes last minute, and from Ford rather than the director. She lashes out - literally slapping Billy Dee Williams (Lando Calrissian). And just as it's all kicking off, David Prowse (Darth Vader) tries to interest the director in his new book on keeping fit!

Fisher surely didn't approve the use of this in the book, or producer Gary Kurtz's comments that she "doesn't always look after herself as she should [and] doesn't pay sufficient attention to proper eating habits" (p. 123). Yet Arnold is also protective of the young actress, such as when she's subjected to a journalist who had got onto the set under false pretences - an experience Fisher describes as akin to a "rape" (p. 81). He's also sensitive to her skills as an actress, inspired by close study of old, silent films that focus on the close-up.

Arnold also reports a spat between Hamill and the director, soon after Hamill's baby son is born. At the time, the fractiousness is put down to Hamill having damaged his thumb (p. 150) which might mean the lightsaber battle that he has trained for will now be performed by a double. The sense is that neither Hamill nor Fisher had any say over this nakedly honest stuff being put in the book; the publicist who ought to have been protecting their interests was the one who wrote it. But later, Hamill at least gets to put this "terribly childish" disagreement in context.

"Our only real flare-up was on the carbon-freezing chamber set. Tempers were on edge anyway because it was like working in a sauna ... "Everybody felt guilty seconds later" (p. 213)

We finish with the film being edited, and Arnold getting lost on his way to the home of John Williams, who is busy composing the score. The book was published in August 1980 to coincide with the release of the film - so there was no way of knowing if all this work was going to pay off. Like the film itself, we leave on a cliffhanger.

Arnold concludes in philosophical mood about the creative arts in general, but more striking is what follows his words: credits listing all the many people involved in making the film.

See also:

Sunday, July 03, 2022

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

"In all his time in camps and prisons, Ivan Denisovich had lost the habit of concerning himself about the next day, or the next year, or about feeding his family. The authorities did all his thinking for him, and, somehow, it was easier like that." (p. 40)

This extraordinary book, detailing the waking hours on a bitterly cold day in a Russian work camp sometime in the early 1950s, is based on the real-life experience of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who was released from such labour in 1957.

First published in the USSR in 1962, my 1970 translation by Gillon Aitken is at least the third version in English. I can see why this book so haunted a generation. It seems to have influenced subsequent memoirs - of Soviet gulags, of the concentration camps in the war, of systems of oppression more generally.

In the USSR, the book and its implicit criticism of the regime overseen by Stalin was initially welcomed - perhaps emblematic of the new, more liberated era of Khrushchev. When Khrushchev was himself stripped of power in 1964, Solzhenitsyn fell out of favour. His books weren't exactly banned in the USSR, but life was made increasingly difficult.

When, in 1969, Solzhenitsyn was chucked out of the Union of Writers in Russia, various bodies around the world staged protests of one kind or another. Most notably, the author was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize for Literature. In July 1969, the Writers' Guild of Great Britain sent two delegates to the International Writers Guild conference being held in Moscow with the specific brief of making some protest about the treatment of Solzhenitsyn. One of those delegates was David Whitaker, and I've been reading his accounts of what happened there - and the fall-out from it. More of that anon.

The book is full of extraordinary moments: the men discussing the merits and techniques of Eisenstein's cinema as they get on with their weary toil in the snow; the man who is in prison because of the heinous crime of having received a note of gratitude from an English admiral after service in the war; the way a prisoner receiving a parcel of food from their family finds themselves in debt to everyone else...

In observing these details within the drudgery, Solzhenitsyn shows us the mechanics of the operation, the way the oppression works. The infighting of prisoners compels them to work, to play an active role in the system imprisoning them.

"Who is the prisoner's worst enemy? Another prisoner. If only the prisoners didn't fight with each other, then..." (p. 114)

And while it's about the system, it's also about how an individual might survive in such conditions. Ivan Denisovich Shukhov hordes a crust of bread, does favours to earn himself an extra bit of thin soup, and squirrels away a broken bit of hacksaw blade with which he can later fashion a knife that will be useful for mending clothes. Only then the prisoners get searched and this small theft risks putting him,

"in the cells on 300 grams of bread a day and hot food once every three days. He imagined at that moment how enfeebled and hungry he would become and how difficult it would be to recover his present condition of being neither starved nor properly fed." (p. 117)

All that effort to keep going could be undone in an instant. And we're left with the horrible fact that this is just one day in 3,653 of Shukov's 10-year sentence. The last line of the book adds one further systematic cruelty.

"The three extra days were because of the leap years..." (p. 157)

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Head of Drama, by Sydney Newman (with Graeme Burk)

Burk had access to the Newman archive, and I'm beside myself with envy at some of the material he's had at his fingertips. The Ur-text of all Doctor Who archaeology is the 1972 book The Making of Doctor Who by Malcolm Hulke and Terrance Dicks. According to Burk, Hulke wrote to Newman on 6 August 1971 asking him for memories of how the programme came about. On 28 September, Newman replied:

“I don't think I'm immodest in saying that it was entirely my concept, although inevitably many changes were brought about by Verity Lambert, who was its first producer. She would be the very best source of information, better than say, David Whitaker or even Donald Wilson.” (pp. 448-449)

However, by the time Newman sent this, Hulke had spoken to Donald Wilson (on 8 September) who told him what's generally considered the fact: that Doctor Who was created by Newman and Wilson.

“It was just Sydney and I together, chatting. At an early stage we discussed it with other people, but in fact the title, as I remember, I invented…” (p. 450)

Burk digs into this, citing some counterclaims, analysing the surviving paperwork from those early days and addressing the issue that some key papers appear to be missing from the archive. I've some more to add to this in my forthcoming book on story editor David Whitaker.

Anyway, Doctor Who is just one of the many, many shows Newman worked on. Head of Drama conveys the extraordinary range and impact of his work, from documentary films to opera and everything in between. There's what he learned from double-checking ticket sales in a cinema and watching the reactions of different audiences to the same film, and what working in newsreel and sport taught him about staging drama. He delights in telling us when he got something wrong - he was against employing chat-show host Ed Sullivan, tried to cancel the Daleks and resisted Donald Wilson in commissioning The Forsyte Saga.

But time and again, Newman's instincts for what would be popular and connect with a broad audience were dead right. Just one example of his many, many insights here:

“I laid down some simple notions [while at ABC]. Some people become physically ill when they see blood, and only a fool wants an audience to puke. Ergo, show blood with care. Some in the audience are daffy with hate, so don’t show them how to make a bomb. Viewers will identify with the innocent character, so being bound and helpless and tortured becomes powerfully disturbing, and that kind of reaction is a turn off. And finally, avoid common, easily available weapons such as a kitchen knife, so as not to provoke a viewer who may be feeling momentary murderous rage to act upon it in the moment.” (p. 304)

Newman gives full credit to the many writers and producers and talented people he worked with, but he's an amazing, funny and honest storyteller. There are some amazing stories here. Just before the Second World War, he was offered a job with Disney but had to head to back to Canada to sort out a visa. On the way, a fellow passenger seems to have reported him - as being an illegal immigrant from Mexico! The result was jail and some very hairy moments, but Newman tells it all with compassion and a wry smile, tying it all into a broader theme of having always been an outsider, an exile. And then he concludes that without this sorry business and the problems of a visa, had he been able to take that Disney job, he'd have ended up drafted into the US army and killed at Iwo Jima.

He shrugs that all off and is then onto the next drama.

Monday, June 27, 2022

Still Life, by Sarah Winman

I loved this strange, big-hearted ramble of a book, its vivid characters, its love of life and the echoing horror of loss. The death of one kindly character late on hits extremely hard. How fitting, too, to fall into a novel all about passion for the art of Urbino and Florence as I drove to the memorial for my old A-level Art History teacher, who on Friday afternoons more than 30 years ago shared his joy at Giotto, Uccello and Massaccio.

Friday, June 17, 2022

Play for Today: The Evolution of Television Drama, by Irene Shubik

The Wednesday Play was a prestigious anthology of (mostly) one-off plays, 182 of them broadcast by the BBC between 1964 and 1970. The series then moved to a different day of the week and, as Play for Today, a further 306 (mostly) one-off plays were broadcast between 1970 and 1984. One of the producers, Irene Shubik published this memoir in 1975 (and produced a revised, updated edition in 2001), detailing how and why plays were put on.

One reason for writing such a book is to have a permanent record of the plays at all. As Shubik says at the end of the book, the most noteworthy episodes were repeated - but usually just once. There was no facility to buy episodes for home viewer or to see them screened anywhere else. In many cases, episodes weren’t kept by the BBC anyway. The British Film Institute, with a remit to collect and preserve key bits of screen culture, lacked the resources to do much.

“All it [the BFI] can do is send its recommended lists to the BBC in the hope that the programmes will not actually have been wiped or junked. Meanwhile, there is no guarantee that a student in a hundred years time, hoping to make a study of English television productions in the 1970s will have sufficient material to do so; most of these ‘chronicles of our times’ will have vanished into the ether, condemned by the sheer weight of their numbers, to oblivion.” (p. 182)

She provides a long list of all the plays broadcast in the series up to 11 December 1972 - a valuable resource in the days before the internet made such things readily available - and then another, shorter version of those plays that she herself oversaw. She divides these plays into chapters based on type or style, and provides us with her insights - how they were commissioned, anecdotes about production, responses they received from the press and public. There's an engaging mix of gossip and technical detail, just the sort of thing I like.

There is a brief history of television drama prior to 1964: BBC Television began in December 1936; in 1937 some 123 plays were broadcast, an “astonishingly high figure” though many “were repeats and most were very short in length, from 10-30 minutes”. The majority were adaptations from stage and prose works,

“But even in 1937 there were two pieces put out which were original commissions for the medium: The Underground Murder Mystery by J Bissell Thomas (lasting ten minutes) and Turn Round by SE Reynolds lasting thirty minutes. These were the first two pieces of original English TV drama.” (p. 33)

Though there continued to be original works in the years that followed, Shubik marks 1953 as a pivotal moment in television drama.

“The reason why certain names keep recurring from that year [1953] Wilson, Kneale, Philip Mackie, John Elliot, and Anthony Stevens, among them, was that a policy had been adopted of putting certain promising writers on the staff, to form a sort of writer’s workshop. The idea was that by adapting and story-editing other people’s scripts, and working close to the productions, this nucleus of writers could best learn about the medium. Hierarchically, the structure of the department was Head of Drama (Michael Barry) and Head of Script Department (Donald Wilson), with a group of writers and directors working on all types of drama (plays, series and serials) under their supervision. … Nigel Kneale was the first writer to be put on this scheme, in 1951 [having] convinced the BBC drama department to give him a contract (at £5 a week), first to adapt one of is own [prose] stories and later (eventually at £15 a week), to become a staff writer and adapter.” (p. 34)

She remarks on how little this was.

The next pivotal moment in her history is the ITV network ABC (covering the Midlands) making Canadian producer Sydney Newman its head of drama in 1958. Two years later, Newman gave Shubik a job as script editor. In 1963, he began as Head of Drama at the BBC and gave Shubik a job there the following year.

There is a lot of Newman’s character, behaviour and appearance. Shubik quotes fellow story editor Peter Luke’s assessment of Newman as “a cross between Genghis Khan and a pussycat”, refers to his “Groucho-Marx-like sense of humour” and thinks him “undoubtedly one of the most dynamic men who ever worked in English television.” (p. 9). She’s good on why Newman had such an impact, too.

For example, “probably the first controversial piece”, or play, broadcast in the UK under Sydney Newman was Ray Rigby's Boy With a Meat Axe. Shubik quotes from the review by Norman Hare in News Chronicle on 22 November 1958: the play “included a murder accusation, a young girl getting drunk, and a street fight … as well as using a lavatory as one of the settings” (p. 25).

Newman wanted contemporary, revenant drama, yet for all his dramatists tackled the issues of the day, Shubik says Newman also “wanted as much variety as possible on the programme and a few plays starring ‘blondes with big boobs’ to temper the gloom” (p. 19). And while ABC drama anthology series Armchair Theatre did well,

“The size of the audience, as Sydney was always modestly reminding us at script meetings, was undoubtedly helped greatly by the fact that the programme followed [variety show] Sunday Night at the London Palladium” (p. 31)

Given this last point, it’s odd that when Shubik devotes a chapter to audience response, she doesn’t think there’s much to be gained from comparisons across genre. This is her on the merits of knowing numbers of viewers and their percentage score for a given programme (the “appreciation index”):

“Within the framework of his own programme, therefore, the producer can get some idea from programme research as to which plays were most watched and most liked; to compare one’s own programme with other types of programmes, for example comedy or documentary or sport, is a useless occupation as it is accepted that audiences for different types of viewing will differ.” (p. 180)

Newman recognised that this simply wasn’t true: a significant number of those watching a variety show would stay on to watch contemporary drama, even if only because they didn’t make the effort to switch off or over. Likewise, when Newman devised Doctor Who, he wanted a new, made-for-television drama that would retain the audience from sports show Grandstand and appeal to those tuning in for pop music show Juke Box Jury. Achieving this not only made Doctor Who a hit but led to the BBC dominating Saturday evening TV.

There’s no mention of Doctor Who here. Sadly, Shubik tells us that her oversight of anthology series Out of the Unknown (sci-fi) and Thirteen Against Fate (adaptations of stories by Georges Simenon) are not within the purview of this book - a shame, as it would be interested to know how she thought her work on these differed to the more prestigious one-off plays. She briefly mentions her time as story editor on Story Parade, and one episode in particular: an adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel (about a detective who is a robot), but doesn’t mention Terry Nation, who adapted it for TV.

What is useful for my research into Doctor Who story editor David Whitaker is the many insights into Sydney Newman: why he broke up the BBC’s drama department (to increase productivity, p. 32); what made him a good producer (“the ability to assess personalities and match talents successfully”, p. 26); what he thought made a good story or script editor (“the courage to tell the author it [a script] was not good enough”, p. 29); what he’d look for when viewing a “producer’s run” of a play in the rehearsal room ( he had a “keen instinct for what was dramatic in a production and what was boring and self-indulgent on the part of the director or actors” and Shubik learned, from him, to “look at an outside rehearsal not as a stage play, but through the eyes of the cameras”, p. 49).

There are other interesting details too - why filming is more expensive than recording on videotape, the practicalities of working with different writers, the buzz of production with limited budget and time. Plus I have another production to add to my list of TV and film made at Grim’s Dyke: an episode of The Wednesday Play by David Rudkin, House of Character, including filming at “Grims Dyke Manor [sic] and Ham House in thick fog” (p. 91), with production beginning in October 1967.

Wednesday, June 15, 2022

Doctor Who Chronicles: 1967

In "From the Archives", I trawl through BBC paperwork to reveal "the story of a turbulent year and last-minute changes in the making of Doctor Who."

In "Life on Mars", I examine the life of writer Brian Hayles, whose "most enduring contribution to Doctor Who was the creation of the Ice Warriors, but this was just part of his prolific output."

If this is your sort of thing - and why in heaven wouldn't it be? - you can still buy my book on the 1967 Doctor Who story The Evil of the Daleks. And there's also the issue of Doctor Who Chronicles for 1965, in which I wrote some stuff.

Wednesday, June 08, 2022

Competition, by Asa Briggs

Very quickly after launching in September 1955, ITV offered more hours of entertainment than the BBC. Advertising revenue also quickly made ITV very profitable - a one-shilling share in 1955 was worth £11 by 1958 (p. 11). With more money on offer, there was a huge flow of talent from the BBC; 500 out of 200 staff members moved to ITV in the first six months of 1956. The result was a desperate need for new people and a sharp rise in fees, doubling the cost of making an hour’s television (p. 18). Audiences responded to the fun, less formal ITV. The low point for the BBC came in the last quarter of 1957,

“when ITV, on the BBC’s own calculations, achieved a 72 per cent share of the viewing public wherever there was a choice.” (p. 20)

A lot of what follows is about the BBC’s concerted efforts to claw back that audience. But the book is as much about rivalry inside the BBC - the infighting of different departments, the effort to make the new BBC-2 different from and yet complementary to BBC-1, and the ascendance of TV over radio.

The latter happens gradually but with telling shifts. Since 1932, the monarch had addressed the nation each Christmas by radio; in 1957, Queen Elizabeth made the first such broadcast on TV (p. 144). That seems exactly on the cusp of the audience making the switch: in 1957 more radio-only licences were issued than radio-and-TV licences (7,558,843 to 6,966,256); in 1958 there were more TV-and-radio than radio-only licenses (8,090,003 to 6,556,347) (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). There’s a corresponding flip in the money spent on the two media: in 1957-8, expenditure on radio was more than on TV (£11,856,120 to £11,149,207); in 1958-9, more was spent on TV than radio (£13,988,812 to £11,441,818), and that gap only continued to widen (source: Appendix C, p. 1007). Yet aspects of BBC culture were slower to shift: Briggs notes that “The Governors … held most of their fortnightly meetings at Broadcasting House [home of radio] even after Television Centre was opened [in the summer of 1960]” (p. 32).

Television was expensive to buy into: the “cheapest Ferguson 17” television receiver” in an advertisement from 1957 “cost £72.9s, including purchase tax” (p. 5). Briggs compares the increased uptake of TV to the ownership of refrigerators and washing machines - 25% of households in 1955, 44% in 1960 - as well as cars (p. 6). So there was more going on that what’s often given as the reason TV caught on - ie the chance to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953. The sense is of new prosperity, or at least an end to post-war austerity. Television was part of a wider cultural movement. The total number of licences issued (radio and TV) rose steadily through the period covered, from 13.98 million in 1956 to 17.32 million in 1974 (source: Appendix A, p. 1005). By 1974, the Report of the Committee on Broadcasting Coverage chaired by Sir Stewart Crawford felt, according to Briggs, that,

“People now expected television services to be provided like electricity and water; they were ‘a condition of normal life’.” (p. 998)

This increase in viewers and therefore in licence fee revenue, plus the competition from ITV, led to a change in attitude at the BBC about the sort of thing they were doing. Briggs notes that the experimentalism of the early TV service gave way to more and more people speaking of “professionalism” - skill, experience and pride in the work being done (p. 24). I’m struck by how those skills was shared and developed:

“The Home Services, sound and television, gain … from the fact that they are part of an organisation of worldwide scope [with staff] freely transferred … from any one part of the corporation to another [meaning that Radio and TV had] a wide field of talent and experience to draw upon in filling their key positions”. (pp. 314-15)

There are numerous examples of this kind of cross-pollination. Police drama Dixon of Dock Green was produced by the Light Entertainment department. Innes Lloyd became producer of Doctor Who at the end of 1965 after years in Outside Broadcasts, which I think fed in to the contemporary feel he brought to the series, full of stylish location filming. Crews would work on drama, then the news, then Sportsview, flitting between genre and form. Briggs cites a particular example of this in two programmes initiated in 1957 following the end of the “toddlers’ truce”.

For years, television was required to stop broadcasting between 6 and 7 pm so that young children could be put to bed and older children could do their homework. But that meant a loss in advertising revenue at prime time, so the ITV companies appealed to Postmaster General Charles Hill, who was eventually persuaded to abolish the truce from February 1957. But what to put into that new slot?

“Both sides [ie BBC and ITV] recognised clearly that if viewers tuned into one particular channel in the early evening, there was considerable likelihood that they would stay with it for a large part of the evening that follows.” (Briggs, p. 160)

The BBC filled the new gap with two innovative programmes aimed at grabbing (and therefore holding) a very broad audience. From Monday to Friday, the slot was filled by Tonight, a current affairs programme that basically still survives today as The One Show. The fact that it remains such a staple of the TV landscape can hide how revolutionary it was:

“Through its magazine mix, which included music, Tonight deliberately blurred traditional distinctions between entertainment, information, and even education; while through its informal styles of presentation, it broke sharply with old BBC traditions of ‘correctness’ and ‘dignity’. It also showed the viewing public that the BBC could be just as sprightly and irreverent as ITV. Not surprisingly, therefore, the programme influenced many other programmes, including party political broadcasts.” (p. 162)

Briggs argues that part of the creative freedom came because Tonight was initially made outside the usual BBC studios and system, as space had been fully allocated while the truce was still in place. The programme was made in what became known as “Studio M”, in St Mary Abbots Place, Kensington. But the key thing is that this informality, the blurring of genre, spread.

“This [1960] was a time when old distinctions between drama and entertainment were themselves becoming at least as blurred as old distinctions between news and current affairs and entertainment.” (p. 195)

|

| Jon Pertwee, Adam Faith Six-Five Special (1958) |

“along with a number of other Saturday programmes, it [Six-Five Special] helped to reconstruct the British Saturday, which had, of course, begun to change in character long before the advent of competitive television [and was, with Grandstand, part of] a new leisure weekend.” (p. 199)

Elsewhere, Briggs notes the impact of TV - especially of ITV - on other forms of entertainment: attendance at football matches and cinemas dropped, with many cinemas closing (p. 185). Large audiences of varied ages were becoming glued to the box. I’d dare to suggest that this was not a “reconstruction” but the invention of Saturday, the later development of Juke Box Jury, Doctor Who, The Generation Game etc all part of a determined, conscious effort to compete with ITV with varied, engaging, good shows.

(On Sundays, the BBC continued to honour the truce, with no programming in the 6-7 slot that might compete with evening church services. From October 1961, the slot was taken by Songs of Praise.)

One key way of making good television was to write especially for the small screen. Briggs, of course, cites Nigel Kneale in this regard - though his The Quatermass Experiment and Nineteen Eight-Four are covered in Briggs’ previous volume. But Stuart Hood in A Survey of Television (1967) notes how sitcom grew out of the demands that TV placed on comedians:

"the medium is a voracious consumer of talent and turns. A comic who might in the [music or variety] halls hope to maintain himself with a polished routine changing little over the years, embellished a little, spiced with topicality, finds that his material is used up in the course of a couple of television appearances. The comic requires a team of writers to supply him with gags, and invention" (Hood, p. 152)

Briggs has more on this. For example, Eric Maschwitz, head of Light Entertainment at the BBC, remarked in 1960 that,

“We believe in comedy specially written for the television medium [and recognise] the great and essential value of writers, [employing] the best comedy writing teams [and] paying them, if necessary, as much as we pay the Stars they write for” (Briggs, p. 196-97)

Briggs makes the point on p. 210 that, “The fact that the scripts were written by named writers - and not by [anonymous] teams - distinguished British sitcom from that of the United States.” Some of these writers, such as Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, became household names. Frank Muir and Denis Norden appear, busy over scripts, in Richard Cawston’s documentary This is the BBC (1959, broadcast on TV in 1960): these are writers as film stars.

Hancock’s Half Hour (written by Galton and Simpson) and Whack-o (written by Muir and Norden) were, Briggs says, among the most popular TV programmes of the period, but he also explains how a technological innovation gave Hancock lasting power.

In August 1958, the BBC bought its first Ampex videotape recording machine. At £100 per tape, and with cut (ie edited) tapes not being reusable, this was an expensive system and most British television continued to be broadcast live and not saved for posterity. (Briggs explains, p. 836n, that Ampex was of more practical benefit in the US, where different time zones between the west and east coasts presented challenges for broadcast.)

From July 1959, Ampex was used to prerecord Hancock’s Half Hour, taking some of the pressure of live performance off its anxious star (p. 212). Producer Duncan Wood, who’d also overseen Six-Five Special, then made full use of Ampex to record Hancock’s Half-Hour out of chronological order,

“allowing for changes of scene and costume … Wood used great skill also in employing the camera in close-ups to register (and cut off at the right point) Hancock’s remarkable range of fascinating facial expressions … Galton and Simpson regarded the close-up as the ‘basis of television.’” (p. 213)

Prerecording allowed editing, which allowed better, more polished programmes. What’s more, prerecording meant Hancock’s Half-Hour could be - and was often - repeated, even after his death. The result was to score particular episodes and jokes - “That’s very nearly an armful” in The Blood Donor - into the cultural consciousness. Another, later comedy series, Dad’s Army, got higher viewing figures when it was repeated (p. 954).

|

| Clive Dunn, Michael Bentine It's a Square World (1963) |

Briggs says of the appeal of the later Monty Python’s Flying Circus (which he insists on referring to as “the Circus” rather than the more common “Python”) that,

“It took basic premises and reversed them. It’s humour, which was visual as much as verbal, again often succeeded in fusing both.” (p. 950)

More than that, it was comedy that spoofed and subverted the structures and furniture of television itself. In this, it surely owed a big debt to Bentine.

He’s not the only one to have been rather overlooked in histories of broadcasting. I’ve seen it said in many different places that Verity Lambert, first producer of Doctor Who, was also at the time,

“the BBC’s youngest, and only female, drama producer” (Archives Hub listing for the Verity Lambert papers)

Yet Briggs cites Dorothea Brooking and Joy Harington as producers of “memorable programmes” for the children’s department, referring to several dramas adapted from books. Harington had also produced adult drama - for example, she oversaw A Choice of Partners in June 1957, the first TV work by David Whitaker (whose career I am researching). In early 1963, “drama and light entertainment productions for children were removed from the Children’s Department,” says Briggs on page 179, with this responsibility going to the newly reorganised Drama and Light Entertainment departments respectively. Lambert may have been the only female producer in the Drama Department at the time she joined the BBC in June 1963. Except that Brooking produced an adaptation of Julius Caesar broadcast in November 1963, and Harington was still around; she produced drama-documentary Fothergale Co. Ltd, which began broadcast on 5 January 1965.

(Paddy Russell’s first credit as a producer was on The Massingham Affair, which began broadcast on 12 September 1964. Speaking of female producers, Briggs mentions Isa Benzie and Betty Rowley, the first two producers of the long-running Today programme on what’s now Radio 4 (p. 223). My sense is that there are many more women in key roles than this history implies.)

Stripped of responsibility for drama and light entertainment, the children’s department was incorporated into a new Family Programming group, headed by Doreen Stephens. According to Verity Lambert, this group was envious of Doctor Who - a programme they felt that they should be making. When, on 8 February 1964, an episode of Doctor Who showed teenage Susan Foreman attack a chair with some scissors, it was felt to break the BBC’s own code on acts of imitable violence. As Lambert told Doctor Who Magazine #235,

“The children’s department [ie Family Programming], who had been waiting patiently for something like this to happen, came down on us like a ton of bricks! We didn’t make the same mistake again.”

Lambert had to write Doreen Stephens an apology, so it’s interesting to read in Briggs that Stephens didn’t think violence on screen was necessarily bad. In a lecture of 19 October 1966, she spoke of “overcoming timidity” in making programmes, and believed that,

“violence and tension [don’t] necessarily harm a child in normal circumstances [while] in middle-class homes of the twenties and thirties, too many children were brought up in cushioned innocence … protected as much as possible from all harsh realities.” (Briggs, p. 347).

|

| "Compulsive nonsense" Doctor Who (1965) |

“The university lecturer Edward Blishen called Doctor Who ‘compulsive nonsense’ [footnote: Daily Sketch, 3 July 1964, quoting a Report published by the Advisory Centre for Education], but there was often shrewd sense there as well. At its best it was capable of fascinating highly intelligent adults.” (p. 424)

Beyond the specific subsection, there are other insights into early Doctor Who, too. For example, Briggs tells us that,

“nearly 13 million BBC viewers had seen Colonel Glenn entering his capsule at Cape Canaveral before beginning his great orbital flight [as the first American in space, 20 February 1962]. An earlier report on the flight in Tonight had attracted the biggest audience hat the programme had ever achieved, nearly a third higher than the usual Thursday figure [footnote: BBC Record, 7 (March 1962): ‘Watching the Space Flight’’]” (p. 844)

Could this have inspired head of light entertainment (note - not drama) Eric Maschwitz to commission - via Donald Wilson of the Script Department - Alice Frick and Donald Bull to look into the potential for science-fiction on TV. Their report, delivered on 25 April that year, is the first document in the paper trail that leads to Doctor Who.

Then there is the impact of the programme once it was on air. On 16 September 1965, Prime Minister Harold Wilson addressed a dinner held at London’s Guildhall to mark ten years of the ITA - and of independent television. Part of Wilson’s speech mentioned programmes that he felt had made their mark. As well as Maigret, starring Wilson’s “old friend Rupert Davies”,

“It is a fact that Ena Sharples or Dr Finlay, Steptoe or Dr Who … have been seen by far more people than all the theatre audiences who ever saw all the actors that strode the stage in all the centuries between the first and second Elizabethan age.” (Copy of speech in R31/101/6, cited in Briggs, p. 497).

Two things about this seem extraordinary. One, Wilson - who was no fan of the BBC, as Briggs details at some length - quotes four BBC shows to one by ITV. And at the time, Doctor Who was not the institution it is now, a “heritage brand” of such recognised value that its next episode will be a major feature in the BBC's centenary celebrations this October. When Wilson spoke, this compulsive nonsense of a series was not quite two years-old.

But such is the power of television...

More by me on old telly:

- Nigel Kneale: a centenary celebration

- The influence of The Inheritors by William Golding on the first Doctor Who story

- A Survey of Television by Stuart Hood

- Mary Whitehouse vs Doctor Who

- Starlight Days, by Cecil Madden

- Writing for Television, by Sir Basil Bartlett

- The Intimate Screen, by Jason Jacobs

- I’m Just the Guy Who Says Action, by Alvin Rakoff

Sunday, April 24, 2022

Nigel Kneale: A Centenary Celebration

The first panel, "Nigel Kneale, Quatermass and the BBC", was chaired by Kneale biographer Andy Murray and featured Dick Fiddy from the BFI, Toby Hadoke and comedian Johnny Mains - the latter daring to admit that he doesn't much like Doctor Who. Kneale famously hated that series, but many of us got into Kneale's work via Doctor Who. I've been trying to puzzle out why, and think a lot of fandom - of anything - is trying to recapture the strong feelings of our past. For those thrilled and terrified by Doctor Who as kids, Kneale offers a grown-up version of those feelings, and - since he was so often borrowed from - an understanding of how they were kindled.

The panel was a good, breezy introduction to Kneale and the impact of his work on television in the 1950s, though a lot of the ground here was familiar to me from Toby's recent Radio 4 Extra programme, Remembering Nigel Kneale, and Cambridge Festival's "Televising the future: Nineteen Eighty-Four and the imagination of Nigel Kneale". I'd also just read Andrew Pixley's 1986 interview with Kneale.

Next up, we watched the extraordinary opening episode of The Quatermass Experiment from 1953 (available on the Quatermass Collection DVD set). It's a while since I'd last seen this, and I'd forgotten how blurry, clunky and techbnobabble-heavy its early scenes are as we watch serious, posh scientists at their desks in a tracking control room. But that soon gives way to the extraordinary sight of a house half-demolished by the world's first crewed space rocket. We see before the characters on screen that there's an old woman trapped in the exposed upstairs; she's played by Katie Johnson who two years later was the similarly dotty Mrs Wilberforce in The Ladykillers, only without her scene-stealing cat. It's just one of a number of well-observed comic characters enlivening the serious horror plot, adding a touch of realism - and fun - to the fantasy.

Having read The Intimate Screen by Jason Jacobs, I can understand why The Quatermass Experiment made such an impact: an original drama for television, rather than an adaptation of a stage play or book, that makes full use of the strengths of the medium to conjure an intimately creepy atmosphere. It's so busy, so populous, so nakedly ambitious - and all broadcast live. All these years later, it is thrilling. No wonder it stuck so powerfully with those who saw it at the time. As several panelists said, Quatermass was a thing that terrified our parents, that we first heard about from them decades afterwards - a folk memory of horror. (My mum says the girls at her school would make a lot of noise at the start of each episode, so the grown-ups in charge would not hear the warning of it not being suitable...)

Next up was Tom Baker in a bookish office to narrate Kneale's short story "The Photograph", in a 1978 episode of Late Night Story - a sort of grown-up Jackanory. It's an unsettling story about a sick child, but I was mostly struck by how little Baker blinked throughout what seemed to be a single take (and presumably involved him reading the story off an autocue).

Then Douglas Weir discussed the the new restoration of Nineteen Eighty Four (1954). The audience gasped at a particular example showing Peter Cushing's Winston Smith walking through Hampstead. The version screened by BBC Four a few years ago had Cushing moving through what looked like silver fog; the restored version shows him moving between trees, individual leaves crisp and clear. (I'm on the new Blu-ray release, by the way, just about audible asking Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray the question about Kneale's never-made scripts.)

Next was the panel "From Taskerlands to Ringstone Round – Nigel Kneale in the 70s", chaired by Howard David Ingham with panelists William Fowler, Una McCormack and Andrew Screen. I've been guilty of overlooking Kneale's 1970s output - The Stone Tape (1972), which I'd at least seen, and the anthology series Beasts (1976), which I haven't yet. That led into a screening of Murrain, Kneale's contribution to a 1975 anthology, Against the Crowd (included on the DVD release of Beasts).

David Simeon - who sadly couldn't be at yesterday's event - plays a vet called to a small village by a farmer played by Bernard Lee from the James Bond films. The farmer has some sick pigs and his water supply has dried up, plus a young boy in the village has had something like flu for a month. The farmer and the villagers think this all the work of a local woman, played by Una Brandon-Jones (who I recognised at once as Mrs Parkin in Withnail & I). The villagers want the vet's help in dealing with her; he's determined to champion science over superstition, insisting that "We can't go back" to the old ways. It's a compelling piece: real, sometimes funny and increasingly sinister. With a start, I recognised some of the scenery: the Curious British Telly site says Murrain was recorded in Wildboarclough, not far from where I now live. A local film for this local person, indeed.

Then Matthew Sweet chaired a panel on "Kneale on Film" with panelists Jon Dear, Kim Newman and Vic Pratt. This covered a lot of stuff I didn't know about: Kneale's work on the movie version of stage plays Look Back in Anger (1959) and The Entertainer (1960), and the mutiny-at-sea story HMS Defiant (1962) - all a long way from the weird-thriller stuff. Because of that, I'd not been much interested; the panel made me want to look them out and understand the weird stuff in context. I want, too, to see his last work, a 1997 episode of legal drama Kavanagh QC.

A clip from the movie version of The Quatermass Xperiment ((1955) showed infected astronaut Victor Carroon (Richard Wordsworth) stalk a Little Girl (Jane Asher), who offers it imaginary cake. Asher then joined us to discuss this early role and her later, more prominent part in The Stone Tape (1972) - which was then shown in full. I'd seen this before, but it was fascinating to see beside Nimbos, who didn't know what was coming, and in the context of the day's other offering. Again what struck me was how funny it was, especially the visual gag of Reginald Marsh's hands being outlandish colours as he experiments with dyes. Toby Hadoke pointed out that Neil Wilson appears as a salt-of-the-earth security guard having been seen as a salt-of-the-earth policeman in The Quatermass Experiment, so I wonder how much Kneale consciously used the same actors over the years.

This was followed by a live reading of Kneale's 1952 radio play, You Must Listen. Mark Gatiss played the lawyer who has a new telephone installed in his office, only to find he can hear a young woman talking sauce to an unheard lover. Again, it's very funny, the lawyer embarrassed and outraged but the telephone staff all keen to listen in on this rude stuff. And then, as before, it becomes ever more sinister as we realise this saucy woman is an echo from the past. In that sense, it dovetails with The Stone Tape from 20 years later, and with elements of the other stuff we'd seen. How well chosen all these examples were; we could see we were engaged in an experiment ourselves, to trace the resonant echoes of Kneale.

By this time Nimbos and I were flagging as the short breaks between screenings had not been long enough for us to eat any food, and I was getting a bit wobbly. So we sadly missed the panel on “'The inventor of modern television': Kneale’s influences and Legacy" chaired by Jennifer Wallis with panelists Stephen Gallagher, Mark Gatiss, Andy Murray and Adam Scovell. The day ended with a screening of the movie Quatermass & The Pit (1967), and then much natter in the bar.

It was all a bit overwhelming. There was the sheer amount of stuff covered and shown, but also the way the selection encouraged us to tease out shared themes, techniques, stylistics. Then there was the visceral thrill of being in company, catching up with so many friends. I had a long drive home today, passing close to Wildboarclough and its Murrain, brain abuzz from things learned and spotted and argued. That's the thing about Kneale, who died in 2006, and the stuff he wrote that was largely screened long before I was born...

It is potent. It is alive.