I knocked through this delicious new Doctor Who novel very quickly, revelling in its fun and invention. It's based on a movie script Tom Baker - the fourth Doctor himself - worked out with co-star Ian Marter in the 1970s. Now Baker and my mate James Goss have turned it into a novel.

I knew the basic story from an old feature in Doctor Who Magazine (issue #379, cover date 28 February 2007, since you weren't asking.) But the novel is a revelation, full of wit and life that didn't quite come across in a dry synopsis. Partly, that's down to the first person narration - a Doctor Who story told by the Doctor, and in more than once sense, too.

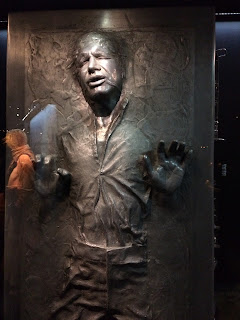

After a prologue in which the Doctor is, yet again, put on trial by his peers - here is Tom Baker reading that prologue - we start with a picnic, the Doctor playing a ukulele to the despair of his friend Sarah, while Harry is keen to play cricket on the beach. But the three friends are watched by sinister scarecrows - including the brilliant mental image of a scarecrow policeman on a bike - and the scarecrows turn out to be linked to Scratchman or, as we better know him, the Devil himself.

In the late 1970s, the proposed film had a director attached: James Hill, who'd later oversee the TV series Worzel Gummidge. I tried to imagine the events of the novel in the same bleak pastoral style, all on film, the scarecrows beautifully realised. That series terrified me as a kid because it seemed so uncannily real. (Not helped by it being shot near where I grew up.)

Scratchman's scarecrows and its depiction of ordinary, village life with its squabbling egos, would suit that kind of production. But as I read the book, I imagined it more in the style of The Android Invasion - a 1975 Doctor Who story about weird goings on in a village, a mix of location recording and studio sets. That story, the last to feature Ian Marter as Harry, is the jolliest of the stories overseen by producer Philip Hinchcliffe, the one most unlike the rest of his tenure. It was directed by his predecessor, Barry Letts, which might account for some of that. But for all the scares and deaths in Scratchman, that's the tone I felt it had. This isn't to criticise the tone - I really like The Android Invasion - but it may explain why Hinchcliffe turned down the proposal to make this for TV.

A few small things also stood out to this tragic fan. On page 92, Sarah sees a picture of herself, "posing while happily hitting her android duplicate with a lump hammer." Surely, the implication is that Scratchman is set after the events of The Android Invasion - with Harry rejoining the TARDIS for more adventures we never saw on TV. Sarah herself was in only four more stories before leaving the TARDIS, so my head has been busy trying to sort out when these new adventures of Harry fit in.

On another occasion, the Doctor lights a cigar from a monster's burning head - a macabre joke, but one that seems out of character for this particular hero. Indeed, on the 1978 story The Stones of Blood, where the Doctor faces execution, Tom Baker changed a line asking for a "last cigarette" to a "last toffee apple." Today, the "rules" about these things are carefully watched over by benign guardians at the BBC, and I imagine they - in their infinite patience and wisdom - made a special exemption here.

Elements of the story also seem familiar from things that have come after it. An awful moment where we learn the life story of one of the scarecrows just before it's destroyed reminded me of things done with the Cybermen in a couple of stories. The Doctor and his friends caught up in a giant game of pinball that then gets mixed up with chess has echoes of the first Harry Potter. Of course, this story was devised first, but we're coming to it new.

The scarecrow with the sad life story is just one of many deaths, many of them involving characters we've come to like, even if we don't always know their names. In fact, a point is made of that when the Doctor claims to remember all those who have died - a scene I thought really powerful. But the emotional impact of the book is more personal and profound. Scratchman wants to know what scares the Doctor, and for all it is played for laughs that is a penetrating question. We get a sense of what it feels like to be the Doctor, to face so much danger and terror, and to carry so much loss. That loss includes himself - the "deaths" of his former selves, and his own impending replacement. There's some fun with this - Baker can't resist a pop at his immediate predecessor not tipping a cab driver, and there's a lovely cameo by one of his future selves where this Doctor tries to be brave about his future. The trial sequence concludes setting up stuff we've since seen on TV involving his successors.

But the most powerful bit is a PS from the Doctor at the almost very end. Here, surely, is not only the Doctor ruminating on his fears, on what it's like to be him, but Tom Baker, too. He concludes with a beautiful blend of pathos and mischief, and it's hard not to think that Baker is 85. He's quite open in interviews that he's a little fragile now and might not be around too much longer. So this ending ties together the boggling ideas of the book but it also feels like goodbye. It's a perfectly judged sign-off and it completely got me. It made this broken old man cry.

Thank you, Doctor. Thanks for everything. Happy times and places to you, too.