Wednesday, November 08, 2023

Who's Views interview about David Whitaker

Tuesday, November 07, 2023

James Beck (Walker in Dad's Army) and David Whitaker

Here are two stills from the earliest known TV appearance by actor James Beck, later famous as spiv 'Joe Walker' in Dad's Army.

|

| Ivor Salter, Ronnie Corbett and James Beck in Crackerjack, BBC TV, 19 March 1958 |

This role in Crackerjack is from three years before what's usually cited as Beck's first TV role - as 'Roach' in The Fifth Form at St Dominic's (1961). (Dave Homewood's exhaustive list of Beck's TV credits says Beck might also have been in episodes of I Made News and Fabian of the Yard in the 1950s.)

The Crackerjack sketch, 'Cops and Robbers', was written by its regular comic guest stars Ronnie Corbett and Michael Darbyshire. Darbyshire receives a visit from Beck's 'Police Inspector Bright', who warns him to be on the look out for a dangerous criminal called 'Kelly' (Ivor Salter). Corbett and Darbyshire are excited by the chance to play Sherlock Holmes and catch the crook. Mayhem ensues...

|

| Radio Times listing for 19 March 1958 with credit for 'David Whittaker' (sic) |

Beck and Whitaker met as actors in repertory theatre in Paignton in the summer of 1955. Two years later, still in Paignton, Beck had a role as 'Arthur Leicester' in A Hand in Marriage, a play David wrote and co-directed. Immediately after this production, David began a full-time job in the Script Unit at the BBC, and quickly worked on a wide variety of shows, Crackerjack among them.

A little after this TV appearance, in October 1958, Beck began a long stint at the York Theatre Royal, where he made life-long friends with a number of other cast members, including Jean Alexander (later 'Hilda Ogden' in Coronation Street), Trevor Bannister (later 'Mr Lucas' in Are You Being Served?), June Barry (later 'Joanie Walker', daughter of Annie, in Coronation Street and also 'June Forsyte' in The Forsyte Saga) and Alethea Charlton (an amazing character actress who later played the cavewoman 'Hur' in the first Doctor Who serial).

That last piece of casting may again have come about through David Whitaker, who was story editor on the first year of Doctor Who. Alethea was also bridesmaid when June Barry married David in the summer of 1963, and James Beck gave away the bride. The gang of friends are all visible in the surviving film from the day, some of which is including in our documentary Looking for David included on the Doctor Who - The Collection: Season 2 box-set.

|

| St Mary Abbots Church, Kensington, 8 June 1963 Groom David Whitaker, bride June Barry, bridesmaid Alethea Charlton, ushers Trevor Bannister and James Beck |

Monday, November 06, 2023

David Whitaker in Sheffield, 1954

One key source was actor Alan Curtis (1930-2021), who was interviewed on 9 April 2014 by my friend Toby Hadoke. This was largely about Alan's role in 1966 Doctor Who story The War Machines, but he also mentioned being friends with David and gave some insights into his character. You can hear that interview in full here:

Prompted by Toby, I visited Alan on 16 August 2016. As well as sharing his memories - which I detail in the book - Alan kindly allowed me to nose through his scrapbooks from 1954, when he and David worked together between March and September as part of the Harry Hanson Court Players repertory company, performing a new play every week at the Lyceum Theatre.

There wasn't a great deal of time and I didn't have the facilities to scan pages from the scrapbook, but I grabbed some snaps thinking I could come back another time - which sadly never happened.

|

| David Whitaker, a photograph I suspect taken before late 1953 when he underwent plastic surgery on his nose. |

|

| "Here Gerard Hely is measured by Iris Gilbert for his costume while David Whitaker, Derek Clark and Louise Jervis break from the Victoria Hall rehearsal to watch." |

|

| Cast list for Reefer Girl, a true story by Lorraine Tier, with David Whitaker in the role of 'John Parsons'. It was performed twice-nightly from Monday, 5 April 1954. |

|

| Cast list for A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, with David Whitaker in the role of 'Howard Mitchell'. It was performed twice-nightly from Monday, 28 June 1954. |

|

| 'Five Hours' Emotion Nightly' - review of A Streetcar Named Desire from unknown newspaper, with David Whitaker bringing 'naive simplicity' to his role. |

|

| Bookmark flyer for the Harry Hanson Court Players, with David Whitaker credited above the title for It's A Boy by Austin Melford, beginning week of 2 August 1954. |

|

| Cast list for Dracula by Bram Stoker, with David in the role of 'Doctor Seward'. It was performed twice-nightly from Monday, 26 July 1954. |

|

| Cast list for Arsenic and Old Lace by Joseph Kesselring, with David in the role of 'Officer O'Hara'. It was performed twice-nightly from Monday, 9 August 1954. |

|

| David Whitaker, standing second from left, in cricket whites and hat as part of the Sheffield Court Players team, which played on Sundays (their day off from the theatre) |

Tuesday, October 24, 2023

The Victorian Chaise-Longue, by Marghanita Laski

“I’ve no idea now why I suggested her," Hussein said earlier this year. Laski was best known at the time as a critic and panelist on TV shows such as What's My Line? But she was also a novelist and of her various novels my bet is that, 60 years ago, Hussein had in mind her odd, 100-page The Victorian Chaise-Longue (1953). He might even have had in mind the TV version: adapted and directed by James MacTaggart, it was screened on BBC Television on 19 March 1962.

The story is told from the perspective of Melanie or Melly Langdon (who has the same initials as Laski), a young woman who has recently given birth to a healthy son but is herself ill with TB. In an attempt to aid her recovery by exposing her to more sunlight, she's allowed out of the confinement of one room in her Islington home and can spend afternoons in the drawing room. There, she lies propped up on an old chaise-longue.

We cut back to her visit to an antique shop (also called a junk shop), seeking a cradle for the then forthcoming baby. There's some fun stuff as she projects an air of idle fancy rather than of being after something specific, to prevent the staff trying to foist something on her for an unreasonable price. This done, she then forms a bond with the young man serving her and they locate the shop's sole cradle - a "hopelessly unfashionable" Jacobean model in dark-carved oak.

“‘I can't say I fancy it myself,’ admitted the young man. ‘It will probably go to America. There's quite a demand for them there, for keeping logs in, you know.’

‘My cradle will have a baby in it,’ said Melanie proudly, and they enjoyed a moment of sympathetic superiority, the poor yet well-adjusted English who hadn't lost sight of true purposes.” (p. 18)

In short, she's a demonstrably intelligent, driven young woman with agency and attitude. When she then spots an old chaise-longue that takes her fancy, she buys it on the spot.

We return to the present - but briefly because soon after the recuperating Melanie/Melly is seated in this antique piece of furniture, she finds herself somewhere else amid people other than her husband. To begin with, Melanie thinks she's been kidnapped but we come to realise that she's been transported back in time 90 years to 22 April 1864 (p. 37), and into the body of another young woman, Milly, who is trapped on the same chaise-tongue while also suffering from TB. At times, Melanie can access Milly's thoughts and memories, and is even swamped by them. She struggles to make her predicament understood and to find a means of escape. As she fails to escape or get through to those around her, she uncovers Milly's awful story.

One issue is that Melanie's knowledge of the 1860s is imperfect and she can't think what to say to convince anyone. Then, when she settles on an idea, there is a further obstacle:

“If I speak of Cardinal Newman and he's happened already, it proves nothing at all. If I could say that the Government will fall and the Prince Consort will die, there's no proof it's going to happen. Discoveries and inventions, she thought then, that's what I'll talk about, that must prove it to him. We have aeroplanes, she said tentatively in her mind, and then she tried to repeat the phrase soundlessly with her mouth, but the exact words would not come. What did I say, she asked herself when the effort had been made, something about machines that fly or was it aeronautic machines? Wireless, she screamed in her mind, television, penicillin, gramophone-records and vacuum-cleaners, but none of these words could be framed by her lips.” (p. 58)

In short, some powerful force prevents her from saying anything aloud that Milly would not understand, which effectively prevents her from altering future history. This is similar to the strictures in the early background notes on Doctor Who revised in July 1963 - soon after Waris Hussein recommended this book - about not being able to change or affect established events.

However, I think I've identified another source for the conception of the mechanics of time travel seen in early Doctor Who, which I get into in my imminent book, David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television (plus details of when Whitaker worked on something with Laski). Instead, I think Hussein was probably thinking of the tone and feel of this short story. The website of Persephone Books, which published the edition of Laski's novel I read, comes with an endorsement by novelist Penelope Lively:

“Disturbing and compulsive ... This is time travel fiction, but with a difference… instead of making it into a form of adventure, what Marghanita Laski has done is to propose that such an experience would be the ultimate terror…”

The first broadcast episodes of Doctor Who are scary, the events an ordeal for the crew. So I wonder if that's what Hussein brought to the series, via Laski...

Oh, and one last excellent fact about Laski, from the introduction by PD James to my edition of the novel:

“In one of her obituaries, Laurence Marks described how she gave evidence in the 1960s for the defence in the prosecution of the publisher of John Cleland's bawdy comic novel, Fanny Hill. Miss Laski told the court that this book was important because it illustrated the first use in English Literature of certain unusual words. The judge asked for an example, to which Miss Laski replied 'chaise-longue'.” (pp. viii-ix)

See also: me on The Inheritors by William Golding (1955) and its influence on the first Doctor Who story

Friday, October 20, 2023

Carrying the Fire, by Michael Collins

A BRILLIANT BOOK

- THE BEST BOOK

WRITTEN BY AN ASTRONAUT

BY SEVERAL MILLION MILES!£2

For another, I've long admired Mike Collins's insightful, wry and funny perspective on that extraordinary mission, having first seen him interviewed in the great Shadow of the Moon, about which I blogged at the time.

Carrying the Fire really is an extraordinary book, written by a then 43 year-old Collins just four years after the Apollo 11 landing took place. He covers flight school, life as a test pilot, then work as an astronaut leading up to Gemini 10 and Apollo 11, and details those flights in depth. We finish with a chapter ruminating on what it all means and, given the extraordinary achievement that nothing can hope to eclipse, what he might now do with his life.

The book is packed with compelling bits of information, such as the first alcoholic drink the Apollo 11 crew had on returning to Earth. There's even a recipe for the martini in question:

"A short glass of ice, a guzzle-guzzle of gin, a splash of vermouth. God, it's nice to be back!" (p. 445)

For me, the first big surprise was a personal one. My late grandfather (d. 2007) was born William and known to his mother and siblings as Bill but to everyone else as "Roscoe", a monicker that has been passed on as a middle name to various of his descendants. According to legend, Grandpa got this nickname on the day he arrived as a gunner in India in the mid-1930s, on the same day that headlines in the local paper declared that, "Roscoe Turner flies in!"

My family had always assumed that this Roscoe Turner was some military bigwig of the time. It was a delight to learn the truth from an astronaut, when Collins explains why he doesn't like to give public speeches.

"In truth, the only graduation speaker to make any lasting impression on me was Roscoe Turner, who in 1953 had come to the graduation of our primary pilot school class at Columbus, Mississippi. The most colourful racing pilot from the Golden Age of Aviation between the world wars, Roscoe had had us sitting goggle-eyed as he matter-of-factly described that wild world of aviation which we all knew was gone forever. ... Roscoe had flown with a waxed mustache and a pet lion named Gilmore, we flew with a rule book, a slide rule, and a computer." (p. 16)

The next surprise related to my research into the life of David Whitaker, whose final Doctor Who story The Ambassadors of Death (1970) involves the missing crew of Mars Probe 7. We're told in the story that this is just the latest in a series of missions to Mars - General Carrington, we're told, flew on Mars Probe 6. - just as the Apollo flights were numbered sequentially. But I think the particular digit was chosen by David Whitaker because of an earlier space programme, as described by Collins.

"The Mercury spacecraft had all been given names, followed by the number 7 to indicate they belonged to the Original Seven [astronauts taken on by NASA]: Freedom (Shepard), Liberty Bell (Grissom), Friendship (Glenn), Aurora (Carpenter), Sigma (Schirra), and Faith (Cooper)." (p. 138n)

(The seventh of the Seven, Deke Slayton, was grounded because of having an erratic heart rhythm.)

That idea of The Ambassadors of Death mashing up elements of Mercury and Apollo has led me to think of some other ways the story mixes up different elements of real spaceflight... which I'll return to somewhere else. On another occasion, Collins uses a phrase that makes me wonder if David Whitaker also drew on technical, NASA-related sources in naming a particular switch in his 1964 story The Edge of Destruction:

"Other situations could develop [in going to the moon] where one had a choice of a fast return at great fuel cost or a slow economical trip home depending on whether one was running short of life-support systems or of propellants." (p. 303 - but my italics)

Collins certainly has a characteristic turn of phrase, such as when he tells us that, "we are busier than two one-legged men in a kicking contest" (p. 219). This makes for engaging, fun commentary yet - ever the test pilot - he's matter of fact about the practicalities of getting bodies to the Moon and back. For example, there's this, at the end of a lengthy description of the interior of the command module Columbia that he took to the moon:

"The right-hand side of the lower equipment bay is where we urinate (we defecate wherever we and our little plastic bags end up), and the left-hand side is where we store our food and prepare it, with either hot or cold water from a little spout." (p. 362)

This kind of stuff is revealing but I knew a lot of it already from my other reading and watching documentaries. What's more of a surprise, coming at this backwards having read later accounts, is the terminology Collins uses. Flights to the moon are "manned" rather than "crewed", and are undertaken with the noblest of intentions for the benefit of all "mankind" - notable now because the language of space travel tends to be much more inclusive. Then there's how he describes one effect of weightlessness:

"I finally realise why Neil and Buzz have been looking strange to me. It's their eyes! With no gravity pulling down on the loose fatty tissue beneath their eye, they look squinty and decidedly Oriental. It makes Buzz look like a swollen-eyed allergic Oriental, and Neil like a very wily, sly one." (p. 387)

It's a shock to read this - and see it reproduced without comment in this 2009 reprint - not least because Collins is acutely aware of the issue of the Apollo astronauts solely comprising middle-aged white men. Elsewhere, he remarks on his own and the programme's unwitting prejudice in the recruitment of further astronauts. In detailing the rigorous selection criteria, he adds:

"I harked back to my own traumatic days as an applicant, or supplicant, and vowed to do as conscientious a job as possible to screen these men, to cull any phonies, to pick the very best. There were no blacks* and no women in the group." (p. 178)

The asterisk leads to a footnote with something I didn't know:

"The closest this country has come to having a black astronaut was the selection of Major Robert H Lawrence, Jr., on June 30, 1967, as a member of the Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory astronaut group. A PhD chemist in addition to being a qualified test pilot, Lawrence was killed on December 8, 1967, in the crash of an F.104 at Edwards AFB. In mid-1969, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program was cancelled." (p. 178n)

But Collins goes on, in the main text, that the lack of women on the programme was a relief.

"I think our selection board breathed a sigh of relief that there were no women, because women made problems, no doubt about it. It was bad enough to have to unzip your pressure suit, stick a plastic bag on your bottom, and defecate - with ugly old John Young sitting six inches away. How about it was a woman? Besides, penisless, she couldn't even use a CUVMS [chemical urine volume measuring system condom receiver], so that system would have to be completely redesigned. No, it was better to stick to men. The absence of blacks was a different matter. NASA should have had them, our group would have welcomed them, and I don't know why none showed up." (p. 178)

Collins is not alone in this view of women in space: as I wrote in my review, Moondust by Andrew Smith goes into much more detail about the problems of plumbing in weightless environments, and the author concludes:

“Even I find it hard to imagine men and women of his generation sharing these experiences.” (Moondust, p. 247)

But that acknowledges the cultural context of these particular men. The lack of women in the space programme is more than an unfortunate technical necessity; it's part of a broader attitude. Collins enthuses about pin-up pictures of young women in his digs during training and on the Gemini capsule, and tells us bemusedly about a hastily curtailed effort to have the young women in question come in for a photo op. It's all a bit puerile, even naive, of this husband and father.

On another occasion, a double entendre shared with Buzz Aldrin leads to a flight of fancy:

"Still... the possibilities of weightlessness are there for the ingenious to exploit. No need to carry bras into space, that's for sure. Imagine a spacecraft of the future, with a crew of a thousand ladies, off for Alpha Centauri, with two thousand breasts bobbing beautifully and quivering delightfully in response to their every weightless movement..." (Collins, pp. 392-3)

I've seen some of this sort of thing in science-fiction of the period. It's all a bit sniggering schoolboy, and lacks the kind of practical approach to problem-solving that makes up most of the rest of the book. How different the space programme might have been if these dorky men had been told about sports bras.

Later, back on earth, Collins shares his misgivings about taking a job as Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs where he was tasked with increasing youth involvement in foreign affairs. He glosses over the conflict here, of talking to "hairies" - as he calls them - on university campuses in the midst of the conflict in Vietnam. One gets the sense that this was a more technically complicated endeavour than his flight to the moon, and less of a success. It's extraordinary to think of this man so linked to such an advanced, technological project and representative of the future put so quickly in a situation where he seems so out of step with the times.

Collins is more insightful as observer of his colleagues' difficulties in returning to earth: Neil Armstrong rather hiding away in a university job, Buzz Aldrin battling demons in LA. In fact, I found this final chapter in many ways the most interesting part of the book, Collins full of disquiet about what the extraordinary venture to the moon might mean, and uncertain of his own future. He died in 2021 aged 90, so lived more than half his life after going to the moon and after writing this book. By the time he wrote it, the Apollo programme had already been cancelled and space travel was being restricted to the relatively parochial orbit of earth.

"As the argument ebbs and flows, I think a couple of points are worth making. First, Apollo 11 was perceived by most Americans as being an end, rather than a beginning, and I think that is a dreadful mistake. Frequently, NASA's PR department is blamed for this, but I don't think NASA could have prevented it." (p. 464)

Collins thinks the American people viewed landing on the moon like any other TV spectacular, akin to the Super Bowl, and so they couldn't then understand the need to repeat it. I'm not sure that's the best analogy given that the Super Bowl is an annual event, but it's intriguing to think of the moon landing as circus. Then again, does that explain the similar loss of interest in the space programme from those outside the US?

I'm more and more interested in the way Apollo was explained and framed for the public at the time...

|

| TV Times listings magazine 19-25 July 1969 "Man on the Moon - ITN takes you all the way" |

- Me on Apollo by Fitch, Baker and Collins

- Me on Ad Astra, An Illustrated Guide to Leaving the Planet by Dallas Campbell

- Me on Moonglow by Michael Chabon

- Me on #Cosmonauts and #OtherWorlds

- "So What If It's All Green Cheese? The Moon on Screen", my essay in the exhibition catalogue accompanying "The Moon" at Royal Museums Greenwich

- "Man on the Moon", my essay on the psychology involved, in medical journal Lancet Psychiatry

Friday, September 29, 2023

David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television - preorder now

Hooray! You can now pre-order ny new book David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television - a 180,000-word biography of the first story editor of Doctor Who, and much more besides. It's published on 6 November.

There are two exciting editions of the book. You can order the paperback directly from publisher Ten Acre Films and it will be available from all good bookshops.

There's also an a fetching, bright pink hardback exclusively from The Who Shop.

There's also an a fetching, bright pink hardback exclusively from The Who Shop.

Both gorgeous covers are by that genius Stuart Manning.

I'll be launching this David Whitaker book at the Portico Library in Manchester on the evening of 9 November. ETA I'll be signing at The Who Ship in London from 1-3 pm on Saturday, 11 November.

Blurb for the book as follows:

To celebrate 60 years of Doctor Who, discover the extraordinary, little-known life of one of its chief architects, David Whitaker. As the show’s first story editor, he helped to establish the compelling blend of adventure, imagination and quirky humour that made – and continues to make – the series a hit.

David commissioned the first Dalek story, and fought for it to be made when his bosses didn’t like it. Regeneration, the TARDIS being alive, the idea of Doctor Who expanding to become a multimedia phenomenon in comics, books and films… David Whitaker was all over it. Yet very little was known about this key figure in Doctor Who history – until now. Why did he fall out with Irving Berlin? Was he really engaged to Yootha Joyce? And how did an assignment to Moscow badly affect his career?

Thursday, August 24, 2023

David Whitaker book launch - 9 November

Full blurb as follows:

To celebrate 60 years of Doctor Who, discover the extraordinary, little-known life of one of its chief architects: David Whitaker. As the show’s first story editor, he helped to establish the compelling blend of adventure, imagination and quirky humour that made — and continues to make — Doctor Who a hit. David commissioned the first Dalek story, and fought for it to be made when his bosses didn’t like it. Regeneration, the TARDIS being alive, the idea of Doctor Who expanding to become a multimedia phenomenon in comics, books and films… David Whitaker was all over it.

Yet very little was known about this key figure in Doctor Who history — until now. Why did he fall out with Irving Berlin? Was he really engaged to Yootha Joyce? And how did an assignment to Moscow badly affect his career? Simon Guerrier, author of a new biography of David Whitaker, will be interviewed by Carol Ann Whitehead. Books will be on sale.

Biographies:

Simon Guerrier has written countless Doctor Who books, comics and audio plays. He’s also the author of Sherlock Holmes — The Great War and had produced a number of documentaries for BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4.

Carol Ann Whitehead is a trustee of the Portico Library, Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts; Deputy Chair of the Chartered Management Institute Women’s Board; and a Chartered Companion. She heads the Zebra Partnership, a boutique publishing, events and campaigns agency.

Ten Acre Films publishes a range of high-quality books on the history of TV, including, most recently, Biddy Baxter: The Woman Who Made Blue Peter and Pull to Open – 1962-1963: The Inside Story of How the BBC Created and Launched Doctor Who.

Sunday, August 20, 2023

Doctor Who Magazine #594

This new issue features the latest instalments of two regular features devised by Marcus and written by me. In All Decs on Hand (my best headline in an age), I interview assistant set decorate Verity Scott and set decorator's assistant Lois Drage. In Sufficient Data, Roger Langridge illustrates my take on the last of the reader's poll winners - this time, the winning stories of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Doctors respectively.

These features will continue under the new editor and we've also been discussing some new things. More of that to come...

By coincidence, I got home to find this new DWM waiting for me after a long drive, in which me and the children were entertained by David Tennant's reading of How to Train Your Dragon (2003) by Cressida Cowell, which was different enough from the films to keep my guessing and is full of fun twists and adventure. It's also fun to hear Tennant's skills as a storytelling with multiple characters and accents, and I quietly thrilled to him referring several times to the 'The Green Death'. But what really struck me - and Lady Vader - is the absence of female characters. A book about young Vikings from another age.

Sunday, May 21, 2023

Trouble with Lichen, by John Wyndham

"It was Diana Brackley who put the milk out for the cat; who dropped a speck of lichen in it by mistake; who noticed how the lichen stopped the milk turning.

But it was Francis Saxover, the famous biochemist, who carried on from there; who developed Antigerone, the cure for ageing; who then tried to suppress a discovery which was certainly in the megaton range.

And so it was Diana Brackley who went to town with Antigerone in one of John Wyndham's gayest and most satirical forays into the fantastic.

'If even a tenth of science fiction were as good, we should be in clover' - Kingsley Amis in the Observer"

It's a remarkable feat, a big science-fiction idea about the way science can affect social change, drawing, I think from the impact of penicillin and of the Suffragette movement, and all conveyed here as light romcom. Brian Aldiss famously criticised Wyndham for writing "cosy catastrophe", but this is all-out fun.

Antigerone slows the biological process, so those who take it do not age. The trouble of the title is that there's only enough of the lichen to make this wonder drug for at most 4,000 people. The result is lots of debate on the ethics of announcing the discovery, let alone deciding who might share its benefits.

Diana is a brilliant character, a young, determined woman with a habit of shocking people by saying the wrong thing - or rather what she thinks. At eighteen, she's asked by a schoolteacher whether her parents are proud of her academic success. Diana responds immediately that her "Daddy's very pleased", but can't say the same for her mother.

"'She tries. She's really been awfully sweet about it,' said Diana. She fixed Miss Benbow with those eyes again. 'Why is that mothers still think it so much more respectable to be bedworthy than brainy?' she inquired. 'I mean, you'd expect it to be the other way round.'

Miss Benbow replies, carefully, that "comprehensible" might be a better word that "respectable", and suggests the possibility that, "when the daughter of a domestic-minded woman chooses to have a career she is criticising her mother by implication".

"'I hadn't looked at it that way before,' Diana admitted thoughtfully. 'You mean that, underneath, they are always hoping that their daughters will fail in their careers, and so prove that they, the mothers, I mean, were right all the time?'" (pp. 12-13)

Diana soon has a career as a brilliant scientist who also likes to look good, and sees no contradiction in using the cutting-edge science she's developed as a beauty treatment for other women. In fact, she sees how the cosmetic aspects of the new discovery can advance the feminist cause. It's not exactly what you expect from a male sci-fi writer of this vintage.

Several of the traits Diana exhibits align with what we'd now think of as autistic and it's refreshing to read a decades-old book that celebrates such diversity. They make her a better character and better person. Sadly, Saxover is less engaging and there's little to explain Diana's long-lasting attraction. His attitude to other women doesn't exactly do him any favours - over pages 25 and 26, he lists the young women who have caused chaos at his laboratory by falling for the men, the women the ones at fault.

Other things are discomforting from a modern perspective. There's a racist joke on page 196 and a general ease with the idea that resources in China should be for the exclusive use of people in the UK. This may be part of the satire. As the situation gets ever more serious, with moral quandaries leading to kidnap and murder, the lightly comic love story gets a little tangled.

"There could have been bloodshed even something like a civil war,"

says one character on page 200, justifying a rash course of action. But there has been bloodshed: this speech comes just 18 pages after an old watchman, Mr Timpson, is killed by the blow from a cosh, a man called Austin is hospitalised and Saxover barely survives a planned arson attack on his home.

I think that mismatch is down to the effort to bridge different forms: science-fiction with the satirical, fantasy on the cusp of what's credible. It's a balancing act, and one that doesn't wholly work in this instance, but it's fascinating to see tried in this way. In fact, that balance is what Wyndham talked about in a 1960 interview for the BBC magazine programme Tonight at the time of publication. How boggling to see him justify this approach and discuss the mechanics of genre on the equivalent of The One Show.

Thursday, May 18, 2023

I Used to Live Here Once, by Miranda Seymour

"The change in Rhys at this point was absolute and devastating. Her loving hosts had become the enemy. Everything they did was wrong. Nicknaming her 'Johnny Rotten' - after the punk prince of bad behaviour - was George's way of trying to dispel a darkness in which no glimmer of light appeared. All their good times had been blotted out. Rhys ranted to everybody who dared to come near her that she was a helpless victim, deserted for weeks on end by a woman who - the unkindest cut of all - produced hideous clothes which her imprisoned guest was then compelled to buy. Even now, Diana was trying to prevent her from going home. Of course, George wrote in his ruefully honest account of the debacle, the converse was true: 'Di could hardly wait.'" (p. 358, citing Melly's "The Old Punk Upstairs", Independent on Sunday, 28 October 1990.)

Throughout her life, Rhys could be rude, aggressive and violent. Yet Seymour makes us sympathetic to Rhys and to those who suffered her "crack-ups".

Of course, that Rhys spent much of her last years feeling trapped in an upstairs room is ironic given her best-known work, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), which (along with Jane Eyre, to which it is a prequel) was one of my A-level English set texts. What will especially linger, I think, is the decades in which Rhys's novel was in gestation, and the role of actress Selma Vaz Dias (1911-77) in reviving Rhys's literary career then seeking to control it. The novel was published when Rhys was in her 70s, the work of a lifetime given the many parallels to her own life which Seymour neatly draws out. No drafts survive, and yet Seymour teases out the development, the competing influences, the story of the book.

There's something, too, in Rhys' various names. She was born Ella Gwendolyn Rees Williams, but took on a number of aliases, as a novelist, a wife and, at the end, a patient - George Melly noted that her hospital bed was labelled "Joan". All these different characters, all these different lives, all inside one person.

Thursday, May 11, 2023

Flesh and Blood, by Stephen McGann

All this activity has meant little time for reading other than checking quotations and references. But last night I finished Flesh and Blood - A History of My Family in Seven Sicknesses by the actor Stephen McGann. He's been tracing his family history since his teens, and follows a line from the the Irish potato famine to the slums of Liverpool and then on to the present day. The Irish history is material he's already mined in the drama he produced and starred in with his three brothers, The Hanging Gale (1995), while it's easy to see how his wife Heidi Thomas has also drawn from personal experience in the series she still oversees, Call the Midwife (2012- ).

Of course, McGann plays kindly, compassionate Dr Patrick Turner in that, which means I heard a lot of the medical explanations in the book in that same warm, reassuring voice. The seven sicknesses - hunger, pestilence, exposure, trauma, breathlessness, heart problems and necrosis - are explained and contextualised in a straightforward, readily comprehensible style.

What really brings the book to life is the specific, human stories - many of which are astonishing. Stephen's great uncle, James McGann, was a fireman on the Titanic, survived the sinking and gave evidence at the enquiry that followed. As a result, his own voice is preserved in the Yorkshire Post of 23 April 1912, an eye witness to the last moments of Captain Smith.

Stephen himself witnessed the disaster at Hillsborough on 15 April 1989 - he was in attendance at the football match, along with his brother Paul. As well as his testimony of what he saw that day, I'm struck by what happened afterwards. It took hours before fans were permitted to leave the ground. And then:

"As Paul and I walked down a Sheffield backstreet, dazed by tragedy and wearing our scarves tight against the evening chill, we suddenly heard a shouted profanity above us, directed against supporters of Liverpool. Pieces of paving stone were thrown from a high balcony in our direction. Shocked out of our daze, we ran for cover." (p. 76)

There's personal tragedy, too, and lots on the mechanics and infighting when you're one of five children - which I found very easy to relate to. There's also McGann's fascination with historical documents, and the sense that going through old papers suddenly gives of your own contribution to history through the papers that bear your name. But what I especially like is how different this is from most biographies and autobiographies.

McGann tells his own and his family's history, but it's actually a history of all of us. How we live. How we sicken and die. What legacy we leave behind us.

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

David Whitaker at 95

|

| David Whitaker in Australia, early 1970s |

In 1963, David became the first story editor of the new science-fiction series Doctor Who, and oversaw of 53 consecutive episodes.

(Two of those weren't broadcast: the unbroadcast pilot was rewritten and re-rerecorded as the broadcast An Unearthly Child, and the two episodes Crisis and The Urge to Live were, after they'd been recorded, edited down into a single episode. I'm not counting the re-recording of The Dead Planet in this total because, so far as we know, the production team worked from the same script so it didn't need David's attention.)

(Also, David didn't receive credit on The Edge of Destruction or The Brink of Disaster because he was the credited writer on those. There's no story editor credited on The Powerful Enemy or Desperate Measures, either, and he may well have written these while still employed as story editor. But paperwork suggested his editorial duties concluded with the episode before that, Flashpoint, so that's where I'm stopping this count. Phew.)

David is also the credited writer on 40 episodes of Doctor Who - more than anyone else in the 1960s, the fourth most prolific TV writer of old-skool Doctor Who (after Robert Holmes on 64, Terry Nation on 56 and Malcolm Hulke on 45 if we count his co-written episodes as 0.5).

Of the 97 missing episodes of Doctor Who, David Whitaker was the credited writer on 18. (John Lucarotti was credited on 11, some co-written, Brian Hayles on 9, Ian Stuart Black on 8.)

David also wrote two of the first three Doctor Who novelisations, co-wrote two of the first three Dalek annuals, co-wrote the first Doctor Who related stage play, polished one of the two Dr. Who movies and probably wrote the bulk of the long running Daleks comic strip.

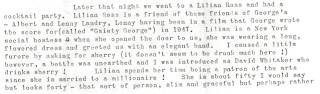

It's the 60th anniversary of Doctor Who this year, so where was David Whitaker on this day in 1963, his 35th birthday? Well, he was in (or just about to go to) New York in an effort to sell a musical he'd written, Model Girl, with composer George Posford.

|

| Excerpt of letter from David Whitaker to June Barry, 30 April 1963 |

Going round the various showbiz houses to schlep his play, he was introduced as, "David Whitaker who drinks sherry."

He returned to the UK around 14 May, presenting his fiancee June Barry with an antique phone, a gift for the flat they were in the process of agreeing to rent after their forthcoming wedding on 8 June.

|

| June Barry in the Daily Mirror, 3 August 1963 |

Yes, that's the same top (and same flat) as seen in a 1965 photo shoot of June and David conducted for TV World - the Birmingham-region version of TV Times.

|

| David Whitaker and June Barry at home, c. May 1965 |

|

| Daily Mirror, 3 July 1963 |

David died in 1980 aged just 51. He was still working on Doctor Who. This form recently came to light, proof (at last!) that he'd been working on a novelisation of his 1967 TV serial The Evil of the Daleks.

I wrote a book about The Evil of the Daleks. Later this year, I've got a book out about another of David's Doctor Who stories, The Edge of Destruction.

You can learn more about David Whitaker in the documentary I worked on with splendid Chris Chapman and Toby Hadoke, on the Season 2 box-set released last year.

And I'm currently writing a ginormous biography, David Whitaker in an Exciting Adventure with Television, to be published by Ten Acre Films later this year. I'll end with this lovely note from David to a young Doctor Who fan in 1964...

|

| Letter from David Whitaker to Doctor Who fan Ian |

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Masquerade: The Lives of Noël Coward, by Oliver Soden

Coward would surely have approved the deft mix of comedy and bathos, and perhaps the stylistic flourishes, too. Some bits are related in script form (Soden's own invention, based on documented sources), and there's a final sequence in which Soden vies with (and rolls his eyes at) Coward's other biographers.

I'm especially impressed by the honesty when historical sources are clearly suggestive but we can't know for sure what went on, such as with Coward's early (sexual?) relationships with men. But what really makes this work is the clarity Soden brings. He unpicks the complexities of a whole bunch of different people who often masked their true selves. And he's good on the impact and response to events - whether that's a review, a break-up, a change in legislation. I'm particularly impressed by how vividly he conveys the war: the horror of the Blitz, the work Coward was given (and not given to do), and how that appeared to those not in the know.

Soden briefly covers the moment when, while shooting In Which We Serve (1942), Coward dressed down an actor for arriving late on set, and fired him in front of the whole crew. The story of William Hartnell's tongue-lashing by Noël Coward is also recounted by the film's assistant director Norman Spencer, who says that the role was quickly filled by assistant director Michael Anderson. Spencer expresses shock at Coward's behaviour, and I wonder how Anderson felt about what happened. He later cast Hartnell in Will Any Gentleman? (1953) -- alongside another future Doctor Who, Jon Pertwee -- and I wonder if that was partly from guilt.

(On 25 November 2009, when we recorded my Doctor Who audio story The Guardian of the Solar System, the two actors were required to read in lines as Hartnell's Doctor. Jean Marsh, who had of course worked with Hartnell, advised Niall McGregor to play him as Noël Coward. Which was more helpful than my recommendation to play him as Professor Yaffle from Bagpuss.)

|

| Philip Streatfeild |

|

| From the index of Masquerade by Oliver Soden |

Soden, in turn, sent me a link to a page about Philip Streatfeild on the Dulwich College website, which includes a poignant letter written by my great-great-grandfather.

Friday, April 07, 2023

The Thirties, by Juliet Gardiner

This annoyance aside, it's another excellent history bringing so much of the past to life. Inevitably, it's not quite as enthralling as the wartime volume, as it can't match that mix of horror, oddness and human interest. I've made numerous notes on stuff that illuminates the early life of David Whitaker for the book I'm writing at the moment. But all sorts of other stuff stands out: the vivid descriptions of the fire that destroyed the Crystal Palace, visible from all over London (from p. 473), or the shocking road-traffic statistics from 1934: 7,343 deaths and 231,603 injuries (p. 679).

Wednesday, March 22, 2023

Beautiful Shadow - A Life of Patricia Highsmith, by Andrew Wilson

It's a fascinating story of a fascinating life. Highsmith is a complex, contradictory subject - on several occasions we're given completely different accounts of her, by turns cruel or kind, quiet or outspoken, fearful or bold. There are lots of reasons not to like her - the racism, the snobbery, the meanness with money when she was so wealthy. Yet understanding her background, her relationship (or lack of it) with her mother and her various struggles and heartbreaks makes this a compelling read.

There are all kinds of odd, striking moments. As well as the snails, there's her short-lived relationship with Tabea Blumenschein,

"the 25 year-old star and producer of the lesbian avant-garde pirate adventure Madame X" (p. 366).

Highsmith and Blumenschein spent six days together in a flat in Pelham Crescent, South Kensington, in May 1978 and at one point browsed the record shops. Blumenschein told Wilson that,

"Pat bought me the Stiff Little Fingers record" (p. 367),

presumably the band's debut single "Suspect Device" (released 4 February that year), before they went to dine with Arthur Koestler. The incongruity of that is even more striking when compared to Highsmith's selection the following year for Desert Island Discs: Bach (twice), Mahler and Mozart, and George Shearing's "Lullaby of Birdland".

A number of things made me begin to suspect that Highsmith was neurodiverse, and late on in the book her friend and neighbour Vivien De Bernardi told Wilson,

"In hindsight, I think Pat could have had a form of high-functioning Asperger's Syndrome. She had a lot of typical traits. She had a terrible sense of direction ... She was hypersensitive to sound and had these communication difficulties. Most of us screen certain things, but she would spit out everything she thought. She was not aware of the nuances of conversation and she didn't realise when she had hurt other people," (p. 394).

De Bernardi said this explains why Highsmith's relationships did not last; I think that's a bit glib - and that Highsmith may also have had some kind of attachment disorder, not helped by her (lack of) relationship with her mother. But I'm struck by De Bernardi's perspective of how this neurodiversity impacted Highsmith the writer:

"Although she didn't really understand other people - she had such a strange interior world - she was a fantastic observer. She would see things that an average person would never experience," (ibid).

Wilson has much to say about the content of and responses to Highsmith's lesbian novel The Price of Salt (1952), later republished as Carol and adapted into the acclaimed film. Highsmith originally published the book under a pseudonym and even when it went out in her own name was guarded in interviews about her sexuality. Often, people who knew Highsmith speak of her attitude to women as if from an outside perspective - as if she were a man. Wilson quotes Highsmith's own cahiers (notebooks) at great length, including a passage from 1942 that is ostensibly about other women and yet surely about herself.

"The Lesbian, the classic Lesbian, never seeks her equal. She is ... the soi-disant [self-styled] male, who does not expect his match in his mate, who would rather use her as the base-on-the-earth which he can never be," (p. 48, quoting Highsmith's Cahier 8, 11/18/42, Swiss Literary Archives in Berne).

Repeatedly, Highsmith identified with her most famous fictional creation Tom Ripley, signing a copy of Ripley Under Ground for her friend Charles Latimer as "from Tom (Pat)," (p. 194, but see pp. 194-6, 199, 350 and 454 for further examples). I now want to reread The Talented Mr Ripley (1955) with all this stuff in mind - from a queer (in the sense of both "strange" and "homosexual"), autistic, trans perspective. It's a book about somebody wanting to be and transforming themselves into someone else; an act of disguise that I think, having read this biography, might be very revealing.

Wednesday, March 15, 2023

Doctor Who Magazine special: Showrunners

Sunday, March 12, 2023

In conversation with Fatima Manji - video

You can now watch the video of my interview with Fatima Manji about her book Hidden Heritage, conducted yesterday as part of Macfest.

"to speak and write in what was then known to Britons as 'Hindustani'; essentially the Hindi and Urdu languages. She learned the Nastaliq writing system of Urdu which itself derives from Persian." (p. 137)

"Victoria's enthusiasm for Urdu, her passion for art and culture of the Orient, and her defence of her friend Abdul Karim are admirable. They are under-reported inspirations in Britain's history for us to draw upon. Yet they cannot whitewash her presiding over a repressive, destructive colonial empire. Ultimately it is the structural, and not the personal, that determined the fate of the millions she ruled." (p. 151)

Wednesday, March 01, 2023

In conversation with Fatima Manji

This free event takes place online from 2 to 3.30 pm. For more details and to book tickets, see the Eventbrite listing for Hidden Heritage: A Fresh Persective. Blurb as follows:

Fatima Manji will be exploring and answering some of the following questions: Why was there a Turkish mosque adorning Britain’s most famous botanic garden in the eighteenth century? How did a pair of Persian-inscribed cannons end up in rural Wales? And who is the Moroccan man depicted in a long-forgotten portrait hanging in a west London stately home?

Throughout Britain’s museums, civic buildings and stately homes, relics can be found that reveal the diversity of pre-twentieth-century Britain and expose the misconceptions around modern immigration narratives.

In her journey across Britain exploring cultural landmarks, Fatima Manji searches for a richer and more honest story of a nation struggling with identity and the legacy of the empire.

‘A timely, brilliant and very brave book’ Jerry Brotton, author of This Orient Isle.