|

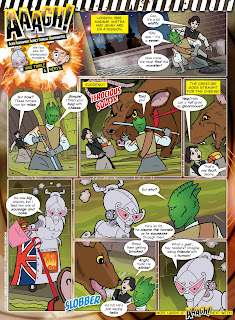

| AAAGH! Steampunk Mrs Tinkle |

Thursday, May 31, 2012

AAAGH! Steampunk Mrs Tinkle

Sunday, May 27, 2012

Three Footnotes from Cosmos

Thanks to lovely Abebooks, I'm now the proud owner of a battered paperback of Carl Sagan's Cosmos and a battered hardback (without dust jacket) of James Burke's Connections – and both for less than a fiver, including P&P. Bargain.

I've been working my way through the TV version of Connections on Youtube and will blog about it more when I get to the end (at my current rate, sometime towards the end of the century). But for a flavour of its style and confidence, you can't beat this extraordinary piece to camera:

I've not seen all the TV version of Cosmos but a lot of the material was covered in my astronomy GCSE, so reading the book has been a bit of a refresher course. It's a history of science, similar to The Ascent of Man, but focusing on our knowledge of astronomy.

It's striking how much has been learned and achieved in the 30 years since the book came out. Sagan details Voyager's exciting new discoveries about the Galilean moons but can only guess at the nature of Titan. He enthuses about the possibility of sending roving machines to explore Mars. He speculates on the causes of the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event (which wiped out the dinosaurs), but doesn't mention the possibility of a large meteorite hitting the Earth. That's especially odd given that elsewhere he talks about the probabilities of large meteorite impacts, such as in Tunguska in 1908.

Sagan packs in fascinating titbits and detail, such as Kepler's efforts to save his mum from being tried as a witch. Excitingly, it's got footnotes instead of endnotes (and an index – so top marks all round), which means plenty of extra nuggets of fact to explode your brain.

For example, Sagan talks at one point about the scale of the Solar System, reminding us that, in terms of our ability to traverse it, the Earth was once a much bigger place. And then he drops in another striking analogy:

I've been working my way through the TV version of Connections on Youtube and will blog about it more when I get to the end (at my current rate, sometime towards the end of the century). But for a flavour of its style and confidence, you can't beat this extraordinary piece to camera:

I've not seen all the TV version of Cosmos but a lot of the material was covered in my astronomy GCSE, so reading the book has been a bit of a refresher course. It's a history of science, similar to The Ascent of Man, but focusing on our knowledge of astronomy.

It's striking how much has been learned and achieved in the 30 years since the book came out. Sagan details Voyager's exciting new discoveries about the Galilean moons but can only guess at the nature of Titan. He enthuses about the possibility of sending roving machines to explore Mars. He speculates on the causes of the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event (which wiped out the dinosaurs), but doesn't mention the possibility of a large meteorite hitting the Earth. That's especially odd given that elsewhere he talks about the probabilities of large meteorite impacts, such as in Tunguska in 1908.

Sagan packs in fascinating titbits and detail, such as Kepler's efforts to save his mum from being tried as a witch. Excitingly, it's got footnotes instead of endnotes (and an index – so top marks all round), which means plenty of extra nuggets of fact to explode your brain.

For example, Sagan talks at one point about the scale of the Solar System, reminding us that, in terms of our ability to traverse it, the Earth was once a much bigger place. And then he drops in another striking analogy:

“In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries you could travel from Holland to China in a year or two, the time it has taken Voyager to travel from Earth to Jupiter.*

* Or, to make a different comparison, a fertilized egg takes as long to wander from the Fallopian tubes and implant itself in the uterus as Apollo 11 took to journey to the Moon; and as long to develop into a full-term infant as Viking took on its trip to Mars. The normal human lifetime is longer than Voyager will take to venture beyond the orbit of Pluto.”

Carl Sagan, Cosmos, p. 159.Like James Burke, Sagan is good at making a connection between two apparently disparate things to create a sense of wonder. But I like how the last sentence of the following footnote so lightly declines to impose or invent a reason:

“The sixth century B.C. was a time of remarkable intellectual and spiritual ferment across the planet. Not only was it the time of Thales, Anaximander, Pythagoras and others in Ionia, but also the time of the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho who caused Africa to be circumnavigated, of Zoroaster in Persia, Confucius and Lao-tse in China, the Jewish prophets in Israel, Egypt and Babylon, and Gautama Buddha in India. It is hard to think these activities altogether unrelated.”

Ibid., p. 206.And, again like Burke, Sagan is good at accounting for chance and circumstance in the slow, steady progress of science through the ages. He uses a Tlingit (Native American) account of meeting the French explorer Count of La Pérouse when he “discovered” Alaska in the 1780s to discuss what first contact with an alien culture might be like. But, explaining that La Pérouse and all but one of his crew died in the South Pacific in 1788, Sagan notes:

“When La Pérouse was mustering the ship's company in France, there were many bright and eager young men who applied but were turned down. One of them was a Corsican artillery officer named Napoleon Bonaparte. It was an interesting branch point in the history of the world. If La Pérouse had accepted Bonaparte, the Rosetta stone might never have been found, Champollion might never have decrypted Egyptian hieroglyphics, and in many more important respects our recent history might have changed significantly.”

Ibid. p 334.Three short asides, additional to the main narrative, and you could base a science-fiction novel on each of them. Yet the thing that's stayed with me most since I finished the book earlier this week is his reference to the 1975 paper “Body Pleasure and the Origins of Violence” by James W Prescott:

“The neuropsychologist James W. Prescott has performed a startling cross-cultural statistical analysis of 400 preindustrial societies and found that cultures that lavish physical affection on infants tend to be disinclined to violence ... Prescott believes that cultures with a predisposition for violence are composed of individuals who have been deprived – during at least one or two critical stages in life, infancy and adolescence – of the pleasures of the body. Where physical affection is encouraged, theft, organized religion and invidious displays of wealth are inconspicuous; where infants are physically punished, there tends to be slavery, frequent killing, torturing and mutilation of enemies, a devotion to the inferiority of women, and a belief in one or more supernatural beings who intervene in daily life.”

Ibid., p. 360.I'm fascinated by this, but can't help wondering if that conclusion isn't too much what we'd like to believe to be true. There's something chilling, too, in the lightness with which he seems to suggest that organised religion is a symptom of childhood neglect.

Thursday, May 24, 2012

AAAGH! A Silent in the Library

|

| AAAGH! A Silent in the Library |

As ever, it's written by me, drawn by Brian Williamson and edited by Natalie Barnes and Paul Lang - who gave permission to post it here. You can also read all my AAAGH!s.

Next time (and in shops at the moment): Steampunk Mrs Tinkle.

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

The end of analogue

|

| Goodbye to all that |

When I bought my flat in 2005, my parents decided it was probably time that I stopped using my old bedroom at their house as a store for my old sci-fi rubbish. One afternoon, my dad drove up with lots and lots of books and two bin bags full of videos. Ah, I can still remember the delighted look on the Dr's face...

(It was not a delighted look on the Doctor's face.)

For readers born after the Flood, video was a slower, chunkier versions of DVD, with a more gravelly image and no special features. (Well, some of the later ones and very brief ones, or came with a separate video providing a commentary track.)

My collection of videos sat in my attic, building up an impressive collection of dust and dead spiders, for the five years I lived in that flat. I gave some away when I could find someone who wanted them. But when we moved home last year, I still had a whole binbag of tapes and nothing to watch any of them on.

I'd looked into selling the tapes, or sending them to people who asked for them, but the hassle of actually packing the damn things kept meaning I never quite got round to it. Videos are heavy, so any kind of postage was going to be stupidly expensive.

But on Sunday, a nice man from the local RSPCA shop came round and took the lot. Having also posted back a tape I borrowed from Ian Potter an aeon ago (with no actual way of watching it), as of Monday - and for the first time since 1984 - I live in a home without videotape.

Yes, I know it's not exactly the most exciting watershed moment in all history, but once the tapes had been taken I must have looked suitably forlorn 'cos the Dr gave me a hug.

(If you want them, the videos will be in the new RSPCA shop opening next month at 267 Lower Addiscombe Road, Croydon, CR0 6RD.)

Saturday, May 19, 2012

"Trying not to break things..."

Will Barber has interviewed me for the Cult Den about the Doctor Who and other things I have written.

Friday, May 11, 2012

The Man Who Made Love To Her

The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) is a really unpleasant book. It's told in the first-person by Vivienne Michel, a young woman running away from her life in England who gets caught up in a nasty scam. The preface says:

Alone and without protection, Vivienne opens the door to two tough hoodlums sent to do the burning – and they thing they might enjoy this girl before murdering her. But then, by chance, a British secret agent just so happens to show up...

Modern, bratty and naïve, Vivienne is quite a departure from previous Bond girls in the books. The first third of the book recounts a rather tawdry love affair in Windsor, with a posh boy who dumps her as soon as he's had his wicked way. It's surprisingly explicit about her first sexual experience, with none of the usual romance and fantasy. She and her lover – Derek – are caught in the act and thrown out of the local cinema, and then get asked questions by a policeman. The sex itself is awkward and uncomfortable.

Vivienne then runs away from England – but nothing changes: she's still the prey of callous men who only want to use her. As a result, the book is all about her as hapless, helpless victim. There's always been a sadistic streak in Bond books, but with the violence focused on Bond himself. He's a tough, determined secret agent, able to defend himself and win despite what's done to him, so the sadism makes him more of a hero. Here, it only makes Vivienne more of a victim.

This means more than that she's just a weak character. I've said before that the best Bond girls are as tough and resourceful as any man. The tougher it is for Bond to impress them and get them into bed, the more that is an achievement (and, as in Moonraker, he's not always successful). So Vivienne's weakness makes Bond look less cool and the book less exciting.

It also doesn't help that Bond arrives to rescue her from the hoodlums quite by chance – on the way home from a far more exciting-sounding story, working with the Mounties to keep a Russian defector called Boris safe from a SPECTRE assassin. It would have been simple enough to connect the hoodlums to SPECTRE, and make Bond's arrival part of his case. The coincidence kills the “realism” that Fleming has otherwise aimed for.

As it is, there's some odd business as Bond has coffee and makes small-talk while the hoodlums try to look innocent. Why don't they just shoot him and get on with their job? Instead, Bond pretends to go to bed, sneaks round and shoots them before they can carry out their threat on Vivienne. She falls gratefully into Bond's arms, but the tone of what happens next is no less nasty:

And Vivienne's point about no girl ever having more of Bond than she did isn't true, either. In the very next book, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, James Bond meets his wife. And it's one of my favourites...

“It's all true – absolutely. Otherwise Ian Fleming would not have risked his professional reputation in acting as my co-author and persuading his publishers to bring out our book. He has also kindly obtained clearance for certain minor breaches of the Official Secrets Act that were necessary to my story.”

Ian Fleming, preface to The Spy Who Loved Me.Perhaps this attempt at realism explains the rather mundane plot. After the outlandish fantasies of the last few Bond books, this feels rather pedestrian. Vivienne is taking care of the Dreamy Pines Motor Court in the north of New York State while the owners are away – but the owners are really planning to burn the place down and claim the insurance, blaming the dead Vivienne for the “accident”.

Alone and without protection, Vivienne opens the door to two tough hoodlums sent to do the burning – and they thing they might enjoy this girl before murdering her. But then, by chance, a British secret agent just so happens to show up...

Modern, bratty and naïve, Vivienne is quite a departure from previous Bond girls in the books. The first third of the book recounts a rather tawdry love affair in Windsor, with a posh boy who dumps her as soon as he's had his wicked way. It's surprisingly explicit about her first sexual experience, with none of the usual romance and fantasy. She and her lover – Derek – are caught in the act and thrown out of the local cinema, and then get asked questions by a policeman. The sex itself is awkward and uncomfortable.

Vivienne then runs away from England – but nothing changes: she's still the prey of callous men who only want to use her. As a result, the book is all about her as hapless, helpless victim. There's always been a sadistic streak in Bond books, but with the violence focused on Bond himself. He's a tough, determined secret agent, able to defend himself and win despite what's done to him, so the sadism makes him more of a hero. Here, it only makes Vivienne more of a victim.

This means more than that she's just a weak character. I've said before that the best Bond girls are as tough and resourceful as any man. The tougher it is for Bond to impress them and get them into bed, the more that is an achievement (and, as in Moonraker, he's not always successful). So Vivienne's weakness makes Bond look less cool and the book less exciting.

It also doesn't help that Bond arrives to rescue her from the hoodlums quite by chance – on the way home from a far more exciting-sounding story, working with the Mounties to keep a Russian defector called Boris safe from a SPECTRE assassin. It would have been simple enough to connect the hoodlums to SPECTRE, and make Bond's arrival part of his case. The coincidence kills the “realism” that Fleming has otherwise aimed for.

As it is, there's some odd business as Bond has coffee and makes small-talk while the hoodlums try to look innocent. Why don't they just shoot him and get on with their job? Instead, Bond pretends to go to bed, sneaks round and shoots them before they can carry out their threat on Vivienne. She falls gratefully into Bond's arms, but the tone of what happens next is no less nasty:

“All women love semi-rape. They love to be taken. It was his sweet brutality against my bruised body that had made his act of love so piercingly wonderful. That and the coinciding of nerves completely relaxed after the removal of tension and danger, the warmth of gratitude, and a woman's natural feeling for her hero. I had no regrets and no shame. There might be many consequences for me – not least that I might now be dissatisfied with other men. But whatever my troubles were, he would never hear of them. I would not pursue him and try to repeat what there had been between us. I would stay away from him and leave him to go his own road where there would be other women, countless other women, who would probably give him as much physical pleasure as he had had with me. I wouldn't care, or at least I told myself that I wouldn't care, because none of them would ever own him – own any larger piece him that I now did. And for all my life I would be grateful to him, for everything. And I would remember him for ever as my image of a man.”

Ian Fleming, The Spy Who Loved Me, p. 154.So the title is a lie. Bond doesn't love her but uses her – as all the other men in her life have, or have tried to – and drives off the next morning, leaving her a note rather than saying goodbye. A more accurate title might be “The Man Who Made Love To Me”. True, he squares things with the police so she won't be in trouble and can collect reward money, but that's surely the least he could do.

And Vivienne's point about no girl ever having more of Bond than she did isn't true, either. In the very next book, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, James Bond meets his wife. And it's one of my favourites...

Thursday, May 10, 2012

AAAGH! The very hungry Master!

|

| AAAGH! from Doctor Who Adventures #267 - the very hungry Master |

Next time: A Silent in the Library!

Wednesday, May 09, 2012

Tales from the TARDIS

Out in shops now is Ace Adventures DVD box, with two Doctor Who stories featuring the Seventh Doctor and his friend Ace. Among the jam-packed jamboree of extras, there's The Doctor's Strange Love, in which me, Joseph Lidster and Josie Long rabbit on about what we like about the first of Ace's stories, Dragonfire. Thrillingly, we got to shoot it out in time and space...

|

| Me, Josie Long and Joe Lidster in the TARDIS. |

|

| The photo Joe took. |

|

| "There are worlds out there where the sky is burning..." |

|

| "What are you young people doing in my TARDIS?" |

|

| Whacky Lidster, thumbs aloft. |

|

| Our "Radio Times" shot. |

|

| Gillane and James, who made our wish come true. Plus my knee. |

|

| I look really bald in this one. |

Sunday, May 06, 2012

What they thought, felt and said

David Lodge’s A Man of Parts is a novel about the life of HG Wells, particularly his sex life. It’s a fascinating, lively read, vividly capturing Wells and the literary and social worlds he moved in. I’ve found it hard to put down, despite a continuing frustration with the book’s two authors – Wells himself and the way Lodge tells the story.

Generally, it’s excellent, such as when detailing Wells’ argument with the Fabians – here a bunch of well-meaning middle-class liberals who want to bring about socialism in Britain, but not so soon as to affect their own cosy standard of living. Wells is much more impatient to bring about social revolution and welfare, what with the practical experience of his youth.

Later still, the dying Wells concludes that the Labour party of 1945 is a creation of these same Fabians, still – despite their campaign for a welfare state – in no rush to deprive themselves of comfort. Even if that was what Wells thought at the time, it sits oddly given that the Labour government brought in such radical social change and nationalisation in the post-war years. They did the things Wells complains they will not do.

I suspect that Wells' remarks are aimed less at his own time as the (New) Labour party of today. Lodge is keen to underline Wells' continuing relevance to us, and the book ends with a rather clumsy metaphor about this common man prophet. On learning of Wells' death, Rebecca West remarks (through Lodge) that Wells was not a meteor who burned brightly once but a comet in a long orbit, whose time will come again.

There's plenty of evidence that Wells was ahead of his time. He lived to see the reality of things he predicted decades before – aerial bombardment of cities and the atomic bomb. But the book credits him with more than he can really have claim to, such as in this clunky bit of wordplay:

For a writer of books ‘of ideas’, Wells’ story is full of human drama which Lodge has mined for psychological detail. We really get under Wells' skin. One highlight is when Wells – himself causing a stir for promoting and living ‘free love’ – discovers that the pious, conservative Hubert Bland (husband of children's author E Nesbit) who opposes him is a serial womaniser whose household includes two children born out of wedlock to his maid. We, too, have come to love the Nesbits and their home, and we, too, feel the vicious betrayal of this hypocrisy.

Yet having followed Wells’ life in detail up to the 1920s, we then rather skip on to the end. The death of his loyal wife Jane is little more than an aside, which is an extraordinary and glaring omission. It's remarked on merely when Wells fears going through his late wife's things and finding evidence that she have had a lover of her own. That's especially strange given how much she's supported him – in his work and his affairs. There's little on what he thought or felt in her final days, or how her illness affected him or made him rethink what he'd done.

Perhaps that would detract from Lodge's sympathetic portrait of Wells, or perhaps Lodge loses interest in Wells once he's peaked as a writer. It seems odd to brush over a decade of the man's life then attempt to sum the whole of him up.

Lodge's Wells is defined by his frustrations – sexual, political and artistic. There's a telling admission in the closing pages:

The book is a fascinating, compelling story full of great anecdotes and insights. But I couldn't shake the sense that it's more about Lodge than it is Wells.

Generally, it’s excellent, such as when detailing Wells’ argument with the Fabians – here a bunch of well-meaning middle-class liberals who want to bring about socialism in Britain, but not so soon as to affect their own cosy standard of living. Wells is much more impatient to bring about social revolution and welfare, what with the practical experience of his youth.

“It wasn’t real poverty. We never starved, but we had a poor diet, which stunted my growth, and made me susceptible to illness. We never went barefoot – but we wore ill-fitting boots and shoes. It was a kind of genteel poverty. I was never allowed to bring my friends home to play because they would see that we couldn't afford a servant, not even the humblest skivvy, and word would get around the neighbourhood. My parents scrimped and saved so they could send me to the cheapest kind of private school, and avoid the shame of a board school, where I might have had better-trained teachers.”It’s a revealing portrait of a lower middle-class existence, all too aware of and aspiring towards a better social standing. But the real skill is in how this description echoes later. Without making a direct link to this earlier passage, Lodge describes Wells – as an established author – wooing the socialist Fabian Society with his essay, The Misery of Boots (1908). There, he uses a working man's ill-fitting boots – the pain and discomfort caused, the effect on the man's posture – to show how poverty defines a person's outlook and ambition, going on to deplore the preventable misery of social injustice and call for the end of private property.

David Lodge, A Man of Parts, p. 45.

Later still, the dying Wells concludes that the Labour party of 1945 is a creation of these same Fabians, still – despite their campaign for a welfare state – in no rush to deprive themselves of comfort. Even if that was what Wells thought at the time, it sits oddly given that the Labour government brought in such radical social change and nationalisation in the post-war years. They did the things Wells complains they will not do.

I suspect that Wells' remarks are aimed less at his own time as the (New) Labour party of today. Lodge is keen to underline Wells' continuing relevance to us, and the book ends with a rather clumsy metaphor about this common man prophet. On learning of Wells' death, Rebecca West remarks (through Lodge) that Wells was not a meteor who burned brightly once but a comet in a long orbit, whose time will come again.

There's plenty of evidence that Wells was ahead of his time. He lived to see the reality of things he predicted decades before – aerial bombardment of cities and the atomic bomb. But the book credits him with more than he can really have claim to, such as in this clunky bit of wordplay:

“I imagined an international Encyclopaedia Organisation that would store and continuously update every item of verifiable human knowledge on microfilm and make it universally available – a world wide web of information.”

Ibid., p. 485.That’s not really a web so much as a centrally controlled giant library. And that word “verifiable” doesn’t exactly describe much of the internet as we know it. I’m wary, anyway, of a writer's worth being judged by how much he guessed correctly. Wells also dreamt up a time-travelling bicycle and invaders from Mars, and those novels are no poorer because they did not happen in reality.

For a writer of books ‘of ideas’, Wells’ story is full of human drama which Lodge has mined for psychological detail. We really get under Wells' skin. One highlight is when Wells – himself causing a stir for promoting and living ‘free love’ – discovers that the pious, conservative Hubert Bland (husband of children's author E Nesbit) who opposes him is a serial womaniser whose household includes two children born out of wedlock to his maid. We, too, have come to love the Nesbits and their home, and we, too, feel the vicious betrayal of this hypocrisy.

Yet having followed Wells’ life in detail up to the 1920s, we then rather skip on to the end. The death of his loyal wife Jane is little more than an aside, which is an extraordinary and glaring omission. It's remarked on merely when Wells fears going through his late wife's things and finding evidence that she have had a lover of her own. That's especially strange given how much she's supported him – in his work and his affairs. There's little on what he thought or felt in her final days, or how her illness affected him or made him rethink what he'd done.

Perhaps that would detract from Lodge's sympathetic portrait of Wells, or perhaps Lodge loses interest in Wells once he's peaked as a writer. It seems odd to brush over a decade of the man's life then attempt to sum the whole of him up.

Lodge's Wells is defined by his frustrations – sexual, political and artistic. There's a telling admission in the closing pages:

“I was outwardly successful – ‘the most famous writer in the world’ – but inwardly dissatisfied. The praise I got was not the kind I wanted or from people I wanted to get it from. It made me arrogant and irritable – I was aware of that, but I couldn’t control myself at times.”

Ibid., p. 499.But I think the most telling statement is Lodge's own, before the novel begins:

“Nearly everything that happens in this narrative is based on factual sources – 'based on' in the elastic sense that includes 'inferable from' and 'consistent with'. All the characters are portrayals of real people, and the relationships between them were as described in these pages. Quotations from their books and other publications, speeches, and (with very few exceptions) letters, are their own words. But I have used a novelist's licence in representing what they thought, felt and said to each other, and I have imagined many circumstantial details which history omitted to record.”

David Lodge, preface to A Man of Parts.There's something deceptive about these words. It's as if what these people thought, felt and said is just a slight embroidery on the solid, historical facts. But invented motives don't just frame what happened, they shape our whole perception of the man and his world. This is not simply a literary biography but a novel with Wells a character of Lodge's own invention, thinking and feeling what Lodge wants him to feel.

The book is a fascinating, compelling story full of great anecdotes and insights. But I couldn't shake the sense that it's more about Lodge than it is Wells.

Friday, May 04, 2012

AAAGH! at the beach!

|

| AAAGH! at the beach |

Next episode: the very hungry Master.

Thursday, May 03, 2012

Doctor Who and the Grontlesnurt Horror

|

| Doctor Who and the Grontlesnurt Horror by me |

Wednesday, May 02, 2012

Revealing Diary - a short film by the Guerrier brothers

SFX exclusively reports that the Guerrier brothers and a handsome gang of desperadoes made a short science-fiction film, Revealing Diary. You can watch it here:

We’re really pleased with the film, which was made as part of Sci-Fi London’s 48-hour challenge (#sfl48hr) – though a last-minute technical hitch meant we missed the deadline.

That’s especially frustrating given the hard work of the cast and crew – who gave their time for free – and the amount of preparation that my brother Tom and I put into it. But we weren’t alone: of 368 entrants, 161 films were submitted. In the hope it helps future entrants – or just because it's of interest to anyone else – here’s what we did and how it went wrong.

I've included links to the cast and crew's Twitter accounts where available. They were amazing and you should give them paid work.

Spoilers obviously follow. Watch the film before proceeding.

HOW WE PREPARED

The competition is to write, shoot and complete a film of between three and five minutes within 48 hours, based on elements given to you at 11 am on the Saturday morning: your film’s title; a line of dialogue; a prop; and an optional scientific theme.

Over the next week, we read the challenge rules, spoke to friends who’d taken part before and watched lots of previous winning and not-winning entries. We made notes on what we saw, and on what we could do that might help our film stand out.

A lot of previous films were set in apocalyptic ruins or wastelands. A lot were very bleak and graded brown and grey. A lot starred men who looked like Tom and me (30-something nerds who needed to shave and spend more time in the gym). So we wanted something present-day, colourful and chirpy, and with prominent roles for women.

Since we – as filmmakers – had to respond to whatever brief we were given, I suggested setting our story in a TV studio. Our characters would be hosting a live, cool show and then respond to some sci-fi event. They might get reports of a plague or alien invasion, or they’d interview the boffin behind some new invention. We gambled on me being able to make that setting work whatever we were given.

Tom planned to shoot most if not all of the film on the Saturday afternoon and evening. If need be, we could shoot a small amount on Sunday morning, but we’d need to wrap by lunchtime so that he could concentrate the remaining hours on the edit, sound mix and grading before delivering the completed film on Monday morning. Again, we gambled that I’d be able to write within that plan.

As our stars, I suggested two actresses I’d worked with since 2008 on Doctor Who and Graceless audio plays for Big Finish (@bigfinish). I rang them both on 4 April and they agreed to take part. My tentative plan was that Ciara Janson (@CiaraJanson)would be a presenter on the TV show and Laura Doddington (@LDoddington)her director.

Tom suggested the other three actors, though we wouldn’t know who they’d play until we got the brief. Once I knew we had Anton Romain Thompson (@This_Is_ART) and Adrian Mackinder (@AdrianMackinder) onboard, and James Rose just for the Sunday, I made notes on possible roles they might play.

For example, Anton was eventually Ciara’s co-presenter, but he could have been a guest – either showing off an invention or giving a first-hand account of some sci-fi event. We asked Adrian to bring a suit to the filming because I thought he might be Laura’s executive producer, arriving in the midst of the crisis and ordering her to change the content of the show… This was as much as I could prepare in advance for whatever brief we got.

Tom also pointed out that a lot of the previous winning films had at least one striking special effect. Tom worked in special effects before becoming a director, so we discussed the kinds of simple but striking effects that were feasible. He made sure our crew included CG supervisor Chris Petts (@ChrisPettsVFX), as well as a strong art direction team in Simon Aronson (@TheMakingSpace) and Gemma Rigg (@MUTEtheFILM). Again, that kept our options open.

I’d had a TV studio in mind for the shoot but it wasn’t available. Tom and I called round various contacts looking for alternatives. On the Tuesday and Wednesday before the challenge, me, Tom and Sebastian Solberg (our Director of Photography, @SebSolberg) visited three possible locations – all working TV studios. Millbank Studios offered us eight hours from noon on the Saturday. At first, this was for more than our budget would allow but they thankfully then offered us a discount.

To give the film a sense of scale, we provisionally planned three ‘sets’ – the studio, the gallery and a green room. Tom suggested that the green room scenes would not need to be recorded at Millbank – where we were on limited time. If those scenes were kept short, we could use another, cheaper location on the Sunday morning. I begged use of a meeting room at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL, which would need minimal set dressing – just a table with a mirror.

Tom planned to have an editor assemble footage while we were still shooting on Saturday and then work through the night, so that we’d have a rough edit of the whole film relatively soon after wrapping on Sunday. We would have a finished edit by about 10 pm.

Tom and I would then stay up Sunday night and Monday morning while the sound design by Tapio Liukkonen at Kaamos Sound, soundtrack by Matthew Cochrane (@matcochr) and grading were completed. It was a tight schedule, but we had a certain amount of “give”. The whole thing had to be made in 48 hours but we were determined to produce a high-quality short.

We were still calling round for crew on the Friday evening – several people were keen but had other commitments, while others (understandably) wouldn’t work for the terms we could offer. Some people could only work one of the two days, or only for a part of the day. But finally we had a full team, including Natasha Phelan (@natashaphelan) as 1st assistant director and Simon Belcher (@nimbos) as sound recordist.

Our crew was largely made up of professionals working in TV and film. Two members of the crew had worked on 48-hour films before. We felt we were as prepared as we could be. But I still hardly slept the night before…

We agreed to meet the cast and crew at 11 am at the Pret down the road from Millbank. I took my laptop, with Final Draft loaded on to it.

OUR BRIEF

I had to write the film based on the brief we were given. Tom received our brief by text message at 11.05:

At noon we moved from Pret to Millbank Studios, where the crew prepared the “set” for filming. They asked me questions as I worked – such as what the live TV show would be called. I needed an answer on the spot. Our given line of dialogue said “by Noon”, so it had to be a late morning show. I suggested “Late Wake Up” and Tom rang Alex Mallinson (@HelloAlexBam) who quickly emailed over different graphics to choose from.

By half twelve, I had a first outline of the script, which Tom read through and made notes on. By one, he’d agreed the script, and Ciara and Laura had their costumes. Tom led us through to the TV studio “set” where the actors read-through what I'd written, with me doing the stage directions. The cast and crew asked questions and clarified some points, we read it again, and by half one we were ready to start filming…

SHOOT

Sebastian (our DoP) shot the film on a tiny, handheld Canon 60D and used a Glidecam 2000 to keep the shot steady. He and Tom went through the shots while I was still writing, working out an opening shot to play the titles over. They went for a fairly standard shooting style, playing the scenes out in their entirety, starting with wides and then shooting close-ups.

We shot everything twice – given the limits on us, that was the quickest and safest way.

We shot quickly, Tom keeping the atmosphere friendly and fun – as you can see from the photos. The first scene took several hours to complete, the longest part of the short. It was quite dialogue heavy, which takes longer to shoot and cut – a lot of competition films had kept the dialogue to a minimum. We made it work because the rest of the film (effectively two scenes) were more visual and could be put together quickly.

Everyone mucked in. Most of the crew appear on screen at some point as extras. There wasn't much need for Chris' VFX brilliance while we shot, so he played the most prominent cameraman. Even Gary, the technician supervising us, had a role in our last shot – that all helped make the film look more expensive.

Chris, Laura and I all took turns holding the boom mike – it's not heavy, but holding it high up and out over the actors is knackering.

Meanwhile, Gemma and Simon hurried to the nearby Oxfam Bookshop to buy a hardback book that Adrian's character could plug on the show. Simon then battled technology to produce a bespoke dust jacket, with Adrian's best photo on the back.

Sunday’s shoot at the Petrie museum should have been quicker, but we’d not anticipated the complexity of the effects shot – and weren’t ready to start filming until after our 1 pm deadline. I'd already agreed to provide some writing work for the museum on a quid pro quo basis. Tom negotiated an extension on the shoot by offering to do some video editing.

The delay was worth it as soon as Gemma and Simon presented the trick effect, and once we were filming we got through the material quickly. We were wrapped and packing up by 3.

We decamped with all our kit to the Marlborough Arms round the corner for much-needed late lunch – and beer. It had been a brilliant, fun shoot, the cast and crew a delight to spend the weekend with.

Tom called the editor to ensure things were on schedule, then stayed for an orange and lemonade with the crew.

THE EDIT – AND CRISIS

Tom and I took a cab to the “unit base” (Genium Creative, the office where Tom works. The editor hadn't finished the edit of all Saturday's footage, so Tom worked on editing the Sunday material and I made a quick dash home.

Having fought the Sunday service on public transport, I was back for half 9 and the takeaway Tom had ordered. Things were going well – and the footage looked amazing.

But as we tried to put the footage from both days together, we discovered a problem with the synching. The more we tried to trace the fault, the more embedded it appeared. Then the computers crashed. At 11 pm – 12 hours from the competition deadline – we effectively had to start the edit again from scratch. We had lost 24 hours of edit time from the 48-hour schedule.

Tom ploughed on anyway, finding me tasks to do such as making tea and compiling the credits. The editor left us at midnight – the time we'd always agreed he would work to.

That was our main failing. If we were doing this again, we'd make sure we had more than one person able to edit footage working through the final night. It would help if I knew how to do some basic assembly – I've since read Roger Corman's advice that the crew should all be competent in every part of production.

The morning wore on. Tom had worked for six hours non-stop when we took stock of the situation. We were both tired, and there was still a lot of work to do. We would be able, Tom thought, to deliver a rough edit of the material to the competition – the scenes in the right order, with basic sound and no grading. Or we could miss the deadline and finish the film later in the week, properly.

We made the decision to hold off and, exhausted, went for breakfast and then home to bed. Later in the morning, Tom emailed the cast and crew to tell them what had happened. Everyone was very supportive – again, a testament to the sense that we'd made something good.

In the next few days, Tom worked on the film, fitting it round other commitments. In principle, he tried to finish it within the time we felt we'd lost, the new cut taking him 12 hours in total. That self-imposed limit proved less practical when it came to tweaking the edit and working on the grade and sound.

It was frustrating to miss the deadline, but we don't regret a thing. We'd strongly recommend taking part in the 48 hour competition, whatever your experience in film-making. Apart from the technical problems at the last minute, we had a brilliant time making our film and have learned a lot that will be very useful on our future projects. We're already planning our next films.

We didn't submit Revealing Diary to the competition because we thought it was a good film in its own right and wanted to finish it properly. We're proud of what we achieved and very grateful to all those people who gave their time and expertise for free.

Sci-Fi London has announced the shortlist of top 20 films from the competition and the winners will be announced this Sunday. Congratulations to them – and to everyone who completed their films on time. We appreciate what an achievement that is.

Simon Aronson has posted more photos from the shoot.

We’re really pleased with the film, which was made as part of Sci-Fi London’s 48-hour challenge (#sfl48hr) – though a last-minute technical hitch meant we missed the deadline.

That’s especially frustrating given the hard work of the cast and crew – who gave their time for free – and the amount of preparation that my brother Tom and I put into it. But we weren’t alone: of 368 entrants, 161 films were submitted. In the hope it helps future entrants – or just because it's of interest to anyone else – here’s what we did and how it went wrong.

I've included links to the cast and crew's Twitter accounts where available. They were amazing and you should give them paid work.

Spoilers obviously follow. Watch the film before proceeding.

HOW WE PREPARED

The competition is to write, shoot and complete a film of between three and five minutes within 48 hours, based on elements given to you at 11 am on the Saturday morning: your film’s title; a line of dialogue; a prop; and an optional scientific theme.

“The 48 hours begins from when all teams have their brief (around Noon on April 14th) and all the creative work must take part in that time period. The only pre-production permissible is the organising of cast and crew (the Team), securing equipment and scouting for possible locations.”

Rule 12 of the 48 hour film challenge rulesTom (the director, @guerrierthomas) and I had talked about the 48-hour challenge before, but started to get serious on 28 March, when Tom emailed to ask if I was free the weekend of 14-16 April. I was, so that was that: we’d do it.

|

| Pre-planning in Starbucks |

A lot of previous films were set in apocalyptic ruins or wastelands. A lot were very bleak and graded brown and grey. A lot starred men who looked like Tom and me (30-something nerds who needed to shave and spend more time in the gym). So we wanted something present-day, colourful and chirpy, and with prominent roles for women.

Since we – as filmmakers – had to respond to whatever brief we were given, I suggested setting our story in a TV studio. Our characters would be hosting a live, cool show and then respond to some sci-fi event. They might get reports of a plague or alien invasion, or they’d interview the boffin behind some new invention. We gambled on me being able to make that setting work whatever we were given.

Tom planned to shoot most if not all of the film on the Saturday afternoon and evening. If need be, we could shoot a small amount on Sunday morning, but we’d need to wrap by lunchtime so that he could concentrate the remaining hours on the edit, sound mix and grading before delivering the completed film on Monday morning. Again, we gambled that I’d be able to write within that plan.

As our stars, I suggested two actresses I’d worked with since 2008 on Doctor Who and Graceless audio plays for Big Finish (@bigfinish). I rang them both on 4 April and they agreed to take part. My tentative plan was that Ciara Janson (@CiaraJanson)would be a presenter on the TV show and Laura Doddington (@LDoddington)her director.

Tom suggested the other three actors, though we wouldn’t know who they’d play until we got the brief. Once I knew we had Anton Romain Thompson (@This_Is_ART) and Adrian Mackinder (@AdrianMackinder) onboard, and James Rose just for the Sunday, I made notes on possible roles they might play.

For example, Anton was eventually Ciara’s co-presenter, but he could have been a guest – either showing off an invention or giving a first-hand account of some sci-fi event. We asked Adrian to bring a suit to the filming because I thought he might be Laura’s executive producer, arriving in the midst of the crisis and ordering her to change the content of the show… This was as much as I could prepare in advance for whatever brief we got.

Tom also pointed out that a lot of the previous winning films had at least one striking special effect. Tom worked in special effects before becoming a director, so we discussed the kinds of simple but striking effects that were feasible. He made sure our crew included CG supervisor Chris Petts (@ChrisPettsVFX), as well as a strong art direction team in Simon Aronson (@TheMakingSpace) and Gemma Rigg (@MUTEtheFILM). Again, that kept our options open.

I’d had a TV studio in mind for the shoot but it wasn’t available. Tom and I called round various contacts looking for alternatives. On the Tuesday and Wednesday before the challenge, me, Tom and Sebastian Solberg (our Director of Photography, @SebSolberg) visited three possible locations – all working TV studios. Millbank Studios offered us eight hours from noon on the Saturday. At first, this was for more than our budget would allow but they thankfully then offered us a discount.

To give the film a sense of scale, we provisionally planned three ‘sets’ – the studio, the gallery and a green room. Tom suggested that the green room scenes would not need to be recorded at Millbank – where we were on limited time. If those scenes were kept short, we could use another, cheaper location on the Sunday morning. I begged use of a meeting room at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL, which would need minimal set dressing – just a table with a mirror.

Tom planned to have an editor assemble footage while we were still shooting on Saturday and then work through the night, so that we’d have a rough edit of the whole film relatively soon after wrapping on Sunday. We would have a finished edit by about 10 pm.

Tom and I would then stay up Sunday night and Monday morning while the sound design by Tapio Liukkonen at Kaamos Sound, soundtrack by Matthew Cochrane (@matcochr) and grading were completed. It was a tight schedule, but we had a certain amount of “give”. The whole thing had to be made in 48 hours but we were determined to produce a high-quality short.

We were still calling round for crew on the Friday evening – several people were keen but had other commitments, while others (understandably) wouldn’t work for the terms we could offer. Some people could only work one of the two days, or only for a part of the day. But finally we had a full team, including Natasha Phelan (@natashaphelan) as 1st assistant director and Simon Belcher (@nimbos) as sound recordist.

Our crew was largely made up of professionals working in TV and film. Two members of the crew had worked on 48-hour films before. We felt we were as prepared as we could be. But I still hardly slept the night before…

We agreed to meet the cast and crew at 11 am at the Pret down the road from Millbank. I took my laptop, with Final Draft loaded on to it.

OUR BRIEF

I had to write the film based on the brief we were given. Tom received our brief by text message at 11.05:

Title: Revealing Diary

Line: I should probably leave around Noon to be safe… Can you make that happen

Prop: “Sketch: We see a character write a list of 6 words, the first word beginning with R (does not need to be a name or real word) – they then do a small doodle by the last word”

Optional: Man in coma explores mind as environmentOnce we got the text message, I had to act quickly, deciding the rough outline and what roles the actors would play. Our costume supervisor Becky Duncan was only available that morning, so once she had a rough brief from me, she quickly took Ciara and Laura up the street to go shopping in Primark. I sat typing the script at my laptop while Tom and the crew discussed how they’d shoot my story. We agreed that Simon A would provide us with a fake book and a trick mirror.

At noon we moved from Pret to Millbank Studios, where the crew prepared the “set” for filming. They asked me questions as I worked – such as what the live TV show would be called. I needed an answer on the spot. Our given line of dialogue said “by Noon”, so it had to be a late morning show. I suggested “Late Wake Up” and Tom rang Alex Mallinson (@HelloAlexBam) who quickly emailed over different graphics to choose from.

|

| The set of Late Wake Up |

SHOOT

Sebastian (our DoP) shot the film on a tiny, handheld Canon 60D and used a Glidecam 2000 to keep the shot steady. He and Tom went through the shots while I was still writing, working out an opening shot to play the titles over. They went for a fairly standard shooting style, playing the scenes out in their entirety, starting with wides and then shooting close-ups.

|

| Shooting |

Everyone mucked in. Most of the crew appear on screen at some point as extras. There wasn't much need for Chris' VFX brilliance while we shot, so he played the most prominent cameraman. Even Gary, the technician supervising us, had a role in our last shot – that all helped make the film look more expensive.

Chris, Laura and I all took turns holding the boom mike – it's not heavy, but holding it high up and out over the actors is knackering.

Meanwhile, Gemma and Simon hurried to the nearby Oxfam Bookshop to buy a hardback book that Adrian's character could plug on the show. Simon then battled technology to produce a bespoke dust jacket, with Adrian's best photo on the back.

|

| Shooting the green room scenes |

The delay was worth it as soon as Gemma and Simon presented the trick effect, and once we were filming we got through the material quickly. We were wrapped and packing up by 3.

We decamped with all our kit to the Marlborough Arms round the corner for much-needed late lunch – and beer. It had been a brilliant, fun shoot, the cast and crew a delight to spend the weekend with.

Tom called the editor to ensure things were on schedule, then stayed for an orange and lemonade with the crew.

THE EDIT – AND CRISIS

Tom and I took a cab to the “unit base” (Genium Creative, the office where Tom works. The editor hadn't finished the edit of all Saturday's footage, so Tom worked on editing the Sunday material and I made a quick dash home.

Having fought the Sunday service on public transport, I was back for half 9 and the takeaway Tom had ordered. Things were going well – and the footage looked amazing.

But as we tried to put the footage from both days together, we discovered a problem with the synching. The more we tried to trace the fault, the more embedded it appeared. Then the computers crashed. At 11 pm – 12 hours from the competition deadline – we effectively had to start the edit again from scratch. We had lost 24 hours of edit time from the 48-hour schedule.

Tom ploughed on anyway, finding me tasks to do such as making tea and compiling the credits. The editor left us at midnight – the time we'd always agreed he would work to.

That was our main failing. If we were doing this again, we'd make sure we had more than one person able to edit footage working through the final night. It would help if I knew how to do some basic assembly – I've since read Roger Corman's advice that the crew should all be competent in every part of production.

The morning wore on. Tom had worked for six hours non-stop when we took stock of the situation. We were both tired, and there was still a lot of work to do. We would be able, Tom thought, to deliver a rough edit of the material to the competition – the scenes in the right order, with basic sound and no grading. Or we could miss the deadline and finish the film later in the week, properly.

|

| We drown our sorrows at 7 am |

In the next few days, Tom worked on the film, fitting it round other commitments. In principle, he tried to finish it within the time we felt we'd lost, the new cut taking him 12 hours in total. That self-imposed limit proved less practical when it came to tweaking the edit and working on the grade and sound.

It was frustrating to miss the deadline, but we don't regret a thing. We'd strongly recommend taking part in the 48 hour competition, whatever your experience in film-making. Apart from the technical problems at the last minute, we had a brilliant time making our film and have learned a lot that will be very useful on our future projects. We're already planning our next films.

We didn't submit Revealing Diary to the competition because we thought it was a good film in its own right and wanted to finish it properly. We're proud of what we achieved and very grateful to all those people who gave their time and expertise for free.

Sci-Fi London has announced the shortlist of top 20 films from the competition and the winners will be announced this Sunday. Congratulations to them – and to everyone who completed their films on time. We appreciate what an achievement that is.

Simon Aronson has posted more photos from the shoot.